This final section in the series will discuss Oracle’s concept of read consistency and how to transfer an architecture built on this concept to Microsoft SQL Server. It will also touch on the application of synonyms (and when NOT to use them) and the importance of change-control processes in database administration.

Oracle Read Consistency and Its Equivalent in SQL Server

Oracle read consistency ensures that all data returned by a single SQL statement originates from a single, specific point in time.

To illustrate, if you execute a SELECT statement at 12:01:02.345 and it takes 5 minutes to process before returning the result set, the return set will only include data committed to the database as of 12:01:02.345. Data added, updated, or deleted during the 5-minute processing period won’t be reflected.

Oracle achieves read consistency by internally timestamping data modifications and constructing the result set from both permanent datafiles and an undo segment (also known as a “rollback segment,” as it was known until version 10g).

For this mechanism to work, the undo information should be preserved. Overwriting it leads to the familiar ORA-01555: snapshot too old error.

Setting aside undo segment management and handling the ORA-01555: snapshot too old error, let’s examine the practical implications of read consistency in Oracle and how to replicate it in SQL Server, which, like other RDBMS implementations (with the potential exception of PostgreSQL), doesn’t inherently support it.

The key takeaway is that reads and writes in Oracle don’t block each other. This means that a long-running query might not return the most up-to-date data.

While non-blocking reads and writes offer an advantage in Oracle and influence transaction scoping, read consistency implies that you might not always have the latest data. This can be acceptable in some cases (like generating a report for a specific time) but problematic in others.

Consider a hotel room reservation system where not having the latest data, even “dirty” or uncommitted data, can be critical. Imagine two agents simultaneously processing room reservations. How do you prevent overbooking?

In SQL Server, you’d initiate an explicit transaction and SELECT a record from the available rooms (from a table or view). Until this transaction is closed (by COMMIT or ROLLBACK), no one else can access the selected room record. While this prevents double-booking, it forces agents to process requests sequentially, potentially causing delays.

Oracle achieves a similar outcome with a SELECT ... FOR UPDATE statement against records matching your criteria.

Note: More efficient solutions exist, such as setting a temporary flag to mark a room as “under consideration” rather than locking access. However, these are architectural solutions, not language-specific options.

Conclusion: Oracle read consistency has its pros and cons. It’s crucial to understand this platform characteristic, especially when migrating code across platforms.

Public (and Private) Synonyms in Oracle and Microsoft SQL Server

“Public synonyms are evil.” This statement, while not exactly my personal discovery, was a belief I held until public synonyms saved the day, week, and year for me.

Creating a CREATE PUBLIC SYNONYM for every object is common practice in numerous database environments (particularly those I’ve worked in but didn’t design) simply because “we’ve always done it that way.”

The sole purpose of public synonyms in these environments was to reference an object without specifying its owner. Unfortunately, this is one poorly thought-out reason to use public synonyms.

However, when implemented strategically and managed effectively, Oracle public synonyms can be invaluable, offering substantial team productivity benefits that outweigh any downsides. Yes, I said “team productivity.” To grasp this, let’s understand name resolution in Oracle.

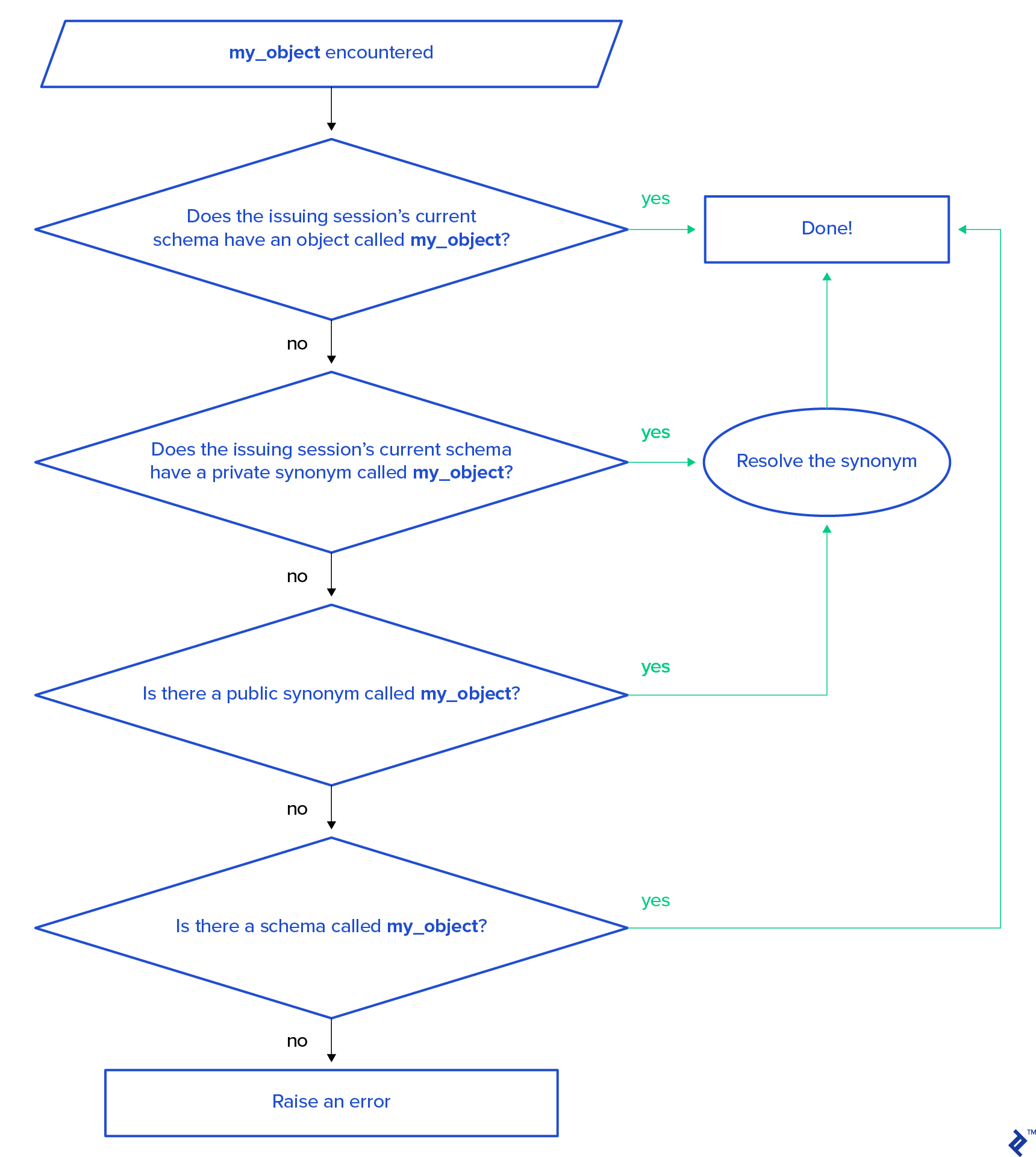

When the Oracle parser encounters a name (a non-reserved keyword), it attempts to match it with an existing database object in this sequence:

Note: DML statements will raise an ORA-00942: table or view does not exist error, while stored procedures or function calls will result in PLS-00201: identifier 'my_object' must be declared.

This resolution order reveals that a local object sharing the same name as a public synonym will mask the public synonym if a developer is working within their own schema. (Note: Oracle 18c introduced the “login-only” schema type, to which this discussion doesn’t apply.)

Public Synonyms for Scaling Teams: Oracle Change Control

Imagine 100 developers working on the same database (a situation I’ve encountered) on their personal workstations. They build non-database code independently but link to a shared development database. Code merging for non-database code (like C#, Java, C++, Python) happens during change-control check-in, taking effect with the next build. However, database tables, code, and data require back-and-forth modifications during development, which each developer does independently, with changes reflected immediately.

To facilitate this, all database objects reside in a common application schema, which the application references. Each developer then follows these steps:

- Connects to the database using their personal account/schema

- Starts with an empty personal schema

- References the common schema exclusively through public synonym name resolution, as explained earlier

When a developer needs to make any database changes (creating or altering tables, modifying procedure code, or even adjusting data for testing), they copy the object into their personal schema. This is achieved by obtaining DDL code using the DESCRIBE command and executing it locally.

From this point onward, the developer’s code interacts with the local object and data versions, invisible to and isolated from others. After development, the modified code is checked into source control, conflicts are resolved, and the final code (and data, if applicable) is implemented in the common schema.

This allows the entire development team to access the same database version again. The developer who delivered the code then cleans up their personal schema by dropping the objects and is ready for the next task.

This capability to support independent, parallel development among numerous developers is the most significant advantage of public synonyms, the importance of which is often overlooked. In practice, I’ve witnessed teams using public synonyms in Oracle implementations simply because “we always do it,” whereas I don’t see it as a standard practice in SQL Server teams. The functionality exists but isn’t widely utilized.

Since Microsoft SQL Server doesn’t automatically associate a new user with their own schema (unlike Oracle), this association should be incorporated into your standard “create user” script.

Here’s a script example for creating dedicated user schemas and assigning them in the DevelopmentDatabase:

First, create individual schemas for each new user in separate batches:

| |

Next, create the first user with their default schema:

| |

Now, user Dev1 has Dev1 as their default schema.

Then, create the second user without a default schema:

| |

User Dev2 will have dbo as their default schema.

Finally, alter user Dev2 to assign their dedicated schema:

| |

User Dev2 now has Dev2 as their default schema.

This demonstrates two ways to assign and modify default schemas for users in Microsoft SQL Server. Since SQL Server supports multiple authentication methods (Windows authentication being the most prevalent) and user onboarding might be managed by system administrators instead of DBAs, the ALTER USER method proves more practical.

Note: I used the same name for the schema and the user. While not mandatory in SQL Server, I prefer this for consistency with Oracle and simplified user management (addressing the primary objection from DBAs). Knowing the username instantly tells you the default schema.

Conclusion: Public synonyms are essential for a robust, multi-user development environment. Sadly, they are often misused, depriving teams of their benefits while leaving them with confusion and other disadvantages. By adopting practices that leverage public synonyms effectively, teams can significantly improve their development workflows.

Database Access Management and Change Management Processes

Having discussed parallel development support for large teams, let’s address a distinct and frequently misunderstood topic: change-control processes.

Change management is often perceived as bureaucratic, controlled by team leads and DBAs, and disliked by developers eager to deliver rapidly.

As a DBA, I always establish safeguards for accessing “my” database, and for a good reason: A database is a shared resource.

While change management is generally accepted in source control (allowing teams to revert to a working state), it can feel restrictive and unnecessary in a database context, hindering development speed.

Setting aside the developer’s perspective, I, as a DBA, understand the need for safeguards when accessing “my” database. A database is a shared resource, and my priority is its stability.

Each development team, and each developer within those teams, has specific objectives and deliverables. However, ensuring the stability of the database as a shared resource remains a constant objective for a DBA. They oversee all development efforts across teams, ensuring projects and processes don’t conflict and have the necessary resources.

Problems arise when development and DBA teams operate in silos. Developers may not fully grasp, have access to, or prioritize what happens on the database as long as it functions for them (it’s not their direct deliverable impacting their evaluation). Meanwhile, DBAs might be overly protective, restricting access and changes to ensure stability, often stemming from a desire to prevent potentially destructive modifications.

Such conflicting approaches can breed animosity and create an unproductive environment. Collaboration between DBAs and developers is essential to achieve their shared goal: delivering a successful business solution.

Having been on both sides, I believe the solution lies in DBAs understanding development teams’ common tasks and objectives. Developers, in turn, need to view the database as a shared resource, with DBAs acting as educators.

A common mistake among non-developer DBAs is restricting developer access to the data dictionary and code optimization tools. Access to Oracle’s DBA_ catalog views, dynamic V$ views, and SYS tables are often considered “DBA privileged” when they are, in fact, crucial development tools.

The same applies to SQL Server, with a slight caveat. Access to some system views can’t be granted directly and is part of the SYSADMIN database role, which should be exclusive to the DBA team. This can be addressed by creating views and stored procedures that execute with SYSADMIN privileges but are accessible to non-DBAs. This is a crucial task for development DBAs when setting up a new SQL Server development environment, especially when migrating from Oracle.

Despite data protection being a core DBA responsibility, it’s not uncommon for development teams to have unrestricted access to production data for troubleshooting data-related issues, while their access to the data structure (which they may have created) is limited.

A well-defined change-control process emerges naturally when a healthy working relationship exists between development and DBA teams. However, managing database changes presents a unique challenge due to the inherent rigidity of the structure and the fluidity of the data.

While change management for structural modifications (DDL) is often well-established, data changes often lack equivalent processes due to their dynamic nature.

Upon closer examination, all data falls into two categories: application data and user data.

Application data, similar to a data dictionary, defines application behavior and is as crucial as the application code itself. Changes to this data warrant stringent change-control processes, just like any other application change. To ensure transparency, explicitly separating application data from user data is essential.

In Oracle, this involves placing them in separate schemas. In Microsoft SQL Server, this can be achieved by using separate schemas or, preferably, separate databases. Consider this during migration planning as Oracle uses two-level name resolution (schema/owner – object name) while SQL Server uses three levels (database – schema/owner – object name).

A common source of confusion between Oracle and SQL Server worlds are—perhaps surprisingly—the terms database and server:

| SQL Server Term | Oracle Term | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| server | database (used interchangeably with server in common parlance, unless referring specifically to server hardware, OS, or network elements; there can be one or more databases on a physical/virtual server) | A running instance that can "talk" to other instances through network ports |

| database (part of a server, contains multiple schemas/owners) | schema/owner | The topmost-level grouping |

This terminology mixup should be clearly understood in cross-platform migration projects because term misinterpretation can result in incorrect configuration decisions that are hard to address retroactively.

This separation allows DBAs to address their other crucial concern: user data security. By isolating user data, implementing a break-glass procedure for user data access becomes straightforward.

Conclusion: Change-control processes are vital for any project. Database-side change management is often overlooked in software engineering due to the perceived “fluidity” of data. However, it’s precisely this characteristic, coupled with data persistence, that makes a robust change-control process crucial for a well-architected database environment.

On the Use of Code Migration Tools

First-party tools like Oracle Migration Workbench and SQL Server Migration Assistant can be useful for code migration. However, it’s crucial to remember the 80/20 rule: While tools might migrate 80% of the code correctly, addressing the remaining 20% often consumes 80% of the effort.

The biggest risk with migration tools is the “silver bullet” misconception. It’s tempting to believe minimal cleanup will be needed. I’ve witnessed projects fail due to this attitude from the conversion team and its leadership.

Conversely, I once converted a mid-sized Microsoft SQL Server 2008 system (around 200 objects) in four working days, primarily using Notepad++’s bulk-replace functionality.

None of the critical migration aspects discussed so far can be fully handled by tools.

While migration assistance tools are helpful, they primarily offer editing support. The output still requires review, modification, and, in some cases, rewriting to ensure production readiness.

Future AI tools might address these limitations. However, I anticipate database differences blurring before then, potentially making migration processes obsolete. Until then, we’ll have to rely on good old-fashioned human intelligence.

Conclusion: While migration assistance tools are beneficial, they are not a “silver bullet.” Conversion projects still demand careful consideration of the points discussed above.

Oracle/SQL Server Migrations: Always Take a Closer Look

Oracle and Microsoft SQL Server are the two most widely used RDBMS platforms in enterprise settings. Both adhere to the ANSI SQL standard, allowing for minimal modifications or even direct migration of small code segments.

This similarity can create a false sense of simplicity when migrating between these platforms, making it seem like switching RDBMS back ends is a trivial task.

In reality, such migrations are far from simple, demanding careful consideration of each platform’s intricacies, especially how they implement the most critical aspect of data management: transactions.

While this discussion focused on my primary areas of expertise, the same warning applies to any SQL-compliant database migration: “looking alike doesn’t mean it works alike.” When moving code between systems, prioritize understanding the differences in transaction management implementations between the source and target platforms.