For years, Android developers and users have grappled with the headache of fragmentation, and it appears the situation might worsen before it improves. The arrival of yet another Android compiler, coupled with significant advancements in hardware, could have a substantial impact on developers.

The anticipated longevity of Google’s 64-bit ART runtime, which replaced Dalvik, remains likely, but a major revamp is on the horizon. ART, with its ahead-of-time (AOT) compilation, was a step up from Dalvik’s just-in-time (JIT) approach. However, the upcoming Optimized compiler promises to unlock even greater potential.

In terms of hardware, new trends are emerging, alongside both familiar and new contenders in the smartphone System-on-Chip arena. More on that later.

Let’s first delve into Google’s runtime plans.

From Dalvik to ART, and Now a New Compiler

Introduced with Android 5.0 in 2014, ART debuted on the Nexus 9 and Nexus 6, though the latter utilized a 32-bit ARMv7-A CPU. ART wasn’t built from the ground up but evolved from Dalvik, shifting away from JIT compilation.

Dalvik’s on-the-fly compilation added to CPU load, increased app launch times, and impacted battery life. Conversely, ART’s AOT compilation at installation eliminates the need for runtime compilation, leading to a smoother user experience, reduced power consumption, and improved battery life.

So, what’s next for Google?

Developed for the new 64-bit ARMv8 CPUs that emerged in late 2014, ART’s initial compiler seems to have been a temporary solution, prioritizing time-to-market over optimization. While ART has been effective and well-received, there’s always room for improvement.

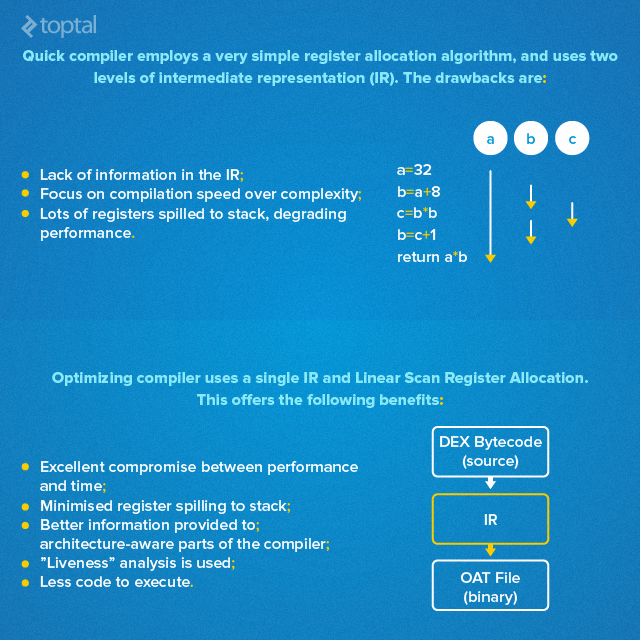

It appears Google has been diligently working on a significantly enhanced compiler, potentially even before ART’s official release. ARM, the British chip designer, recently shed light on Google’s runtime roadmap, hinting at a new “Optimizing” compiler for ART. This compiler employs intermediate representations (IR), allowing for program structure manipulation prior to code generation. Its use of a single, information-rich graph as an IR provides more comprehensive information for the architecture-aware components of the compiler.

In contrast, the “Quick” compiler’s two-level IR, using basic linked lists for instructions and variables, loses crucial information during IR creation.

ARM asserts that the “Optimizing” compiler represents a substantial advancement in compiler technology, offering several key advantages. Its improved infrastructure paves the way for future optimizations and enhances code quality.

“Optimizing” vs. “Quick” Compilers: A Closer Look

ARM highlighted the differences between the two compilers, emphasizing the “Optimizing” compiler’s superior register utilization, reduced stack spilling, and more concise code execution.

Here’s ARM’s take:

Quick’s register allocation algorithm is overly simplistic:

- Limited IR information

- Prioritizes compilation speed over complexity due to its JIT origins

- Subpar performance with excessive register spilling to the stack

Optimizing leverages Liner Scan Register Allocation:

- Strikes an excellent balance between performance and compilation time

- Utilizes liveness analysis

- Minimizes register spilling to the stack

Despite being under development, the “Optimizing” compiler has demonstrated impressive performance gains of 15-40% in synthetic CPU tests, along with an 8% increase in compilation speed. However, ARM cautions that these figures are subject to change as the compiler matures.

The current focus is on achieving performance comparable to the “Quick” compiler, which currently excels in compilation speed and file size.

The trade-off is evident: the “Optimized” compiler excels in CPU-bound applications and benchmarks but results in 10% larger files that compile 8% slower. While the performance gains may outweigh the latter factors, it’s essential to consider their impact on every app, regardless of CPU usage. Increased RAM and storage demands, particularly with 64-bit compilation, are a concern.

Any reduction in compilation speed and launch times raises concerns about device responsiveness and user experience.

The Multicore ARM Landscape

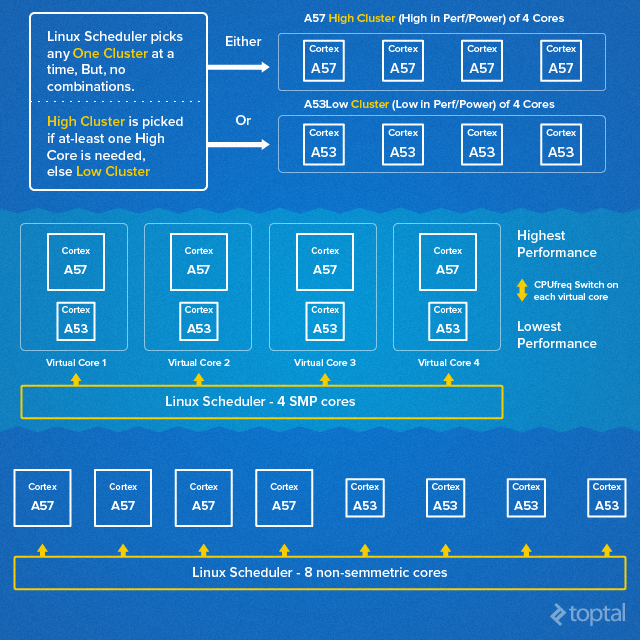

The proliferation of multicore processors based on ARMv7-A and ARMv8 architectures presents another challenge. The octa-core trend, initially dismissed as a marketing ploy in 2013, has gained traction.

Interestingly, a Qualcomm executive who once criticized octa-core processors as “silly” and “dumb” and Apple’s A7 64-bit support as a “gimmick” now finds himself with a different job title on his nameplate.

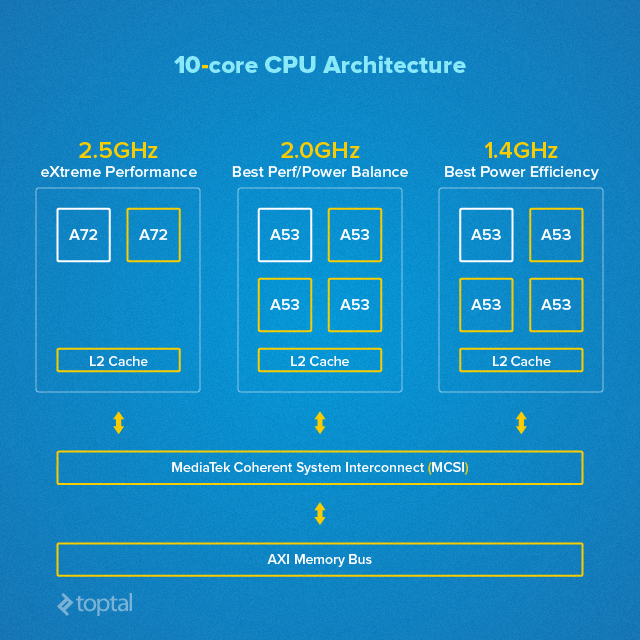

As if eight cores weren’t enough, 10-core application processors are on the horizon. MediaTek’s upcoming Helio X20, featuring three CPU core clusters (huge.Medium.TINY), exemplifies this trend. Adding to the excitement, affordable Android devices with a new generation of Intel processors are also anticipated.

Let’s examine the ARM core landscape and its implications for developers and users.

Two primary ARM SoC octa-core designs exist. High-end solutions often utilize ARM’s big.LITTLE layout architecture, incorporating four low-power and four high-performance cores. The alternative involves using identical cores or two clusters with varying clock speeds.

Leading mobile chipmakers leverage both approaches, employing big.LITTLE designs for high-end devices and standard octa-cores for mainstream products. Let’s analyze the pros and cons of each.

big.LITTLE vs. Regular Octa-Core: A Comparative Analysis

Big.LITTLE designs, with their distinct CPU core clusters, offer excellent single-thread performance and efficiency. However, a single Cortex-A57 core is comparable in size to four Cortex-A53 cores, making it less efficient.

Employing eight identical cores or two clusters with varying clock speeds proves cost-effective and power-efficient but compromises single-thread performance.

Current-generation big.LITTLE designs based on ARMv8 cores face limitations with the cost-effective 28nm manufacturing process. Even at 20nm, performance throttling is prevalent. Conversely, standard octa-cores with Cortex-A53 cores can be efficiently implemented at 28nm, eliminating the need for cutting-edge (and expensive) nodes like 20nm or 16/14nm FinFET.

While I’ll spare you the intricacies of chip design, here are some key takeaways for mobile processors in 2015 and 2016:

- The dominance of 28nm manufacturing and Cortex-A53 cores will impact single-thread performance.

- The large Cortex-A57 core features in Samsung and Qualcomm designs, while others await the Cortex-A72.

- Multithreaded performance will gain importance over the next 18 months.

- Substantial performance leaps hinge on the affordability of 20nm and FinFET nodes (2016 onwards).

- 10-core designs are on the horizon.

These trends have implications for Android developers. With the prevalence of 28nm processes, maximizing multi-threaded performance and prioritizing efficiency are paramount.

ART and new compilers should enhance performance and efficiency, but they can’t defy physics. Legacy 32-bit designs are being phased out, with even budget devices adopting 64-bit processors and Android 5.0.

Android 5.x adoption is steadily increasing and is poised to accelerate with the arrival of affordable 64-bit devices. The transition to 64-bit Android is progressing smoothly.

The timing of the “Optimized” compiler’s arrival for Dalvik remains uncertain, with possibilities ranging from later this year to next year’s Android 6.0.

Heterogeneous Computing: A New Frontier for Mobile

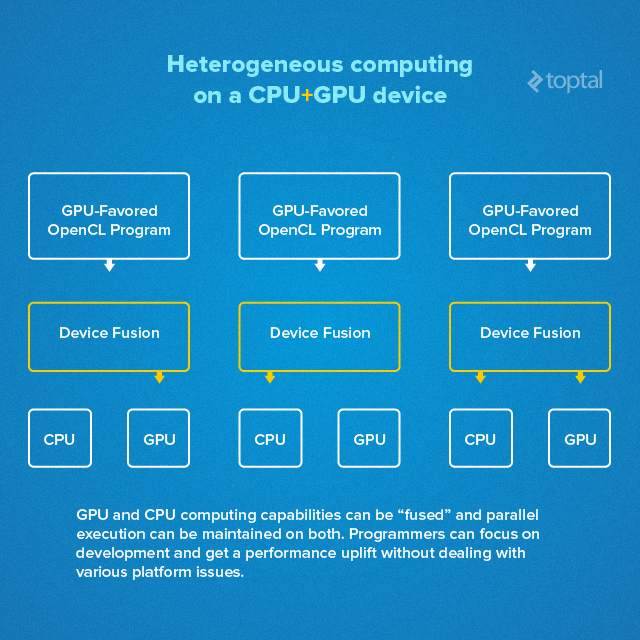

The increasing power of mobile graphics, particularly in high-end processors, has prompted chipmakers to explore their potential beyond gaming and video decoding. Heterogeneous computing, a technology that allows PCs to offload parallelized tasks to the GPU, is making its way to mobile.

This CPU-GPU fusion empowers developers to unlock greater performance by offloading specific tasks, particularly OpenCL loads, to the GPU. The focus shifts to throughput, while the processor automatically manages parallel execution across CPU and GPU cores.

While not universally applicable, this approach should enhance performance and reduce power consumption in specific scenarios. The SoC will dynamically determine the optimal code processing pathway, leveraging both CPU and GPU capabilities.

Given its focus on parallelized applications, this approach is expected to yield significant advancements in image processing. For instance, super-resolution and image resampling tasks could be divided into distinct OpenCL stages. The hardware can then efficiently distribute tasks like find_neighbor, col_upsample, row_upsample, sub, and blur2 between CPU and GPU cores, optimizing performance and power consumption.

Intel’s Resurrection: A Promising Comeback?

Having missed the mobile revolution, Intel practically handed the market to ARM and its partners. However, the chip giant possesses the resources for a comeback.

Last year, Intel’s subsidized Atom processors for tablets led to a fourfold increase in shipments. The company is now targeting smartphones with its new SoFIA Atom x3 processors processors. These budget-friendly chips, developed and manufactured in collaboration with Chinese companies using the 28nm node, might not even qualify as true Intel processors.

Contrary to expectations, Intel isn’t pursuing the high-end mobile market. Instead, SoFIA processors will power affordable Android devices priced between $50 and $150, primarily targeting Asian and emerging markets. While some devices might reach North America and Europe, the focus remains on China and India.

Intel is also hedging its bets with Atom x5 and x7 processors processors, featuring a new architecture and the company’s cutting-edge 14nm manufacturing process. However, these chips are destined for tablets, at least initially.

The million-dollar question is how many design wins Intel can secure. Analyst estimates vary widely.

Intel’s willingness to endure losses to penetrate the tablet market is evident. Whether the same strategy will be employed for Atom chips, particularly SoFIA products, remains to be seen.

A $69 Chinese tablet with 3G connectivity is the only Intel SoFIA-based device I’ve encountered. Considering this is essentially an oversized phone, entry-level SoFIA phones could be significantly cheaper. The prospect of “Intel Inside” branding on budget-friendly devices is undoubtedly enticing for white-box manufacturers.

However, Intel’s phone and tablet shipment figures remain speculative. While millions of units are anticipated, the exact volume is unclear. With analysts predicting 20-50 million Atom x3 processor shipments this year, Intel’s share of the projected 1.2 billion smartphone market remains small. However, with its resources and aggressive approach, capturing 3-4% of the market by the end of 2015 seems achievable, with further growth anticipated in 2016 and beyond.

Implications for Android Developers

Intel’s reputation among Android developers has been marred by compatibility issues stemming from hardware differences compared to ARM cores.

Fortunately, Intel has made significant strides, offering comprehensive training, documentation, and actively recruiting Android developers.

While progress is evident, challenges remain. My recent experience with an Intel Atom Z3560-powered Asus phone, despite being a capable platform, revealed occasional app crashes, unrealistic benchmark results, and other compatibility quirks. Addressing hardware-specific issues can be frustrating for developers. While obtaining Intel devices for testing is recommended, Intel’s efforts to resolve these issues are encouraging.

In the ARM realm, expect more CPU cores and clusters. Single-thread performance on mainstream devices, particularly those with Cortex-A53 SoCs, will likely remain constrained. The potential impact of Google/ARM compilers on these devices is yet to be determined. Heterogeneous computing is another trend to monitor.

In summary, here’s what Android developers should anticipate in late 2015 and 2016:

- Increased adoption of Intel x86 processors in entry-level and mainstream devices.

- Gradual growth of Intel’s market share from a negligible level in 2015.

- Emergence of more ARMv8 multicore designs.

- Arrival of the new “Optimized” ART compiler.

- Gradual adoption of heterogeneous computing.

- Performance and feature enhancements with the transition to FinFET nodes and the Cortex-A72.