Creating robust code can be a difficult task. While libraries, frameworks, and APIs can become outdated quickly, mathematical principles and patterns endure. These concepts, often the result of years of dedicated research, can outlive both technologies and individuals.

This isn’t a guide on using a specific library but rather a deep dive into the fundamental principles of functional and reactive programming. Our goal is to equip you with the knowledge to build resilient and adaptable Android architecture that can withstand the test of time and changing requirements without compromising on performance.

This article establishes the groundwork, and in Part 2, we’ll delve into implementing functional reactive programming (FRP), a powerful blend of functional and reactive programming.

While tailored towards Android developers, the concepts presented here are applicable to any programmer familiar with general-purpose programming languages.

Functional Programming 101

Functional programming (FP) is a paradigm where programs are constructed by chaining together functions. These functions transform data in a series of steps, like $A$ to $B$, then $B$ to $C$, and so on, until the desired outcome is reached. Unlike object-oriented programming (OOP) where you instruct the computer step-by-step, FP involves defining a “recipe of functions” to achieve the desired result, relinquishing control over the precise execution flow.

FP has its roots in mathematics, specifically lambda calculus, a system of logic focused on function abstraction. Rather than relying on OOP concepts like loops, classes, polymorphism, or inheritance, FP works exclusively with abstraction and higher-order functions—mathematical functions that can take other functions as arguments.

In essence, FP revolves around two primary components: data (the model or information needed for the task) and functions (representing actions and transformations on data). This contrasts with OOP, where classes inherently link specific data structures (and their associated values or state) with methods designed to operate on them.

Let’s break down three fundamental aspects of FP:

- FP is declarative.

- FP relies on function composition.

- FP functions are pure.

A great starting point for your FP journey is Haskell, a strictly typed, purely functional language. I highly recommend the Learn You a Haskell for Great Good! interactive tutorial.

FP Element #1: Declarative Programming

One of the first things you’ll notice about FP code is its declarative style, as opposed to an imperative one. Simply put, declarative programming focuses on defining what the program should accomplish, rather than dictating how to do it. To illustrate the difference between imperative and declarative programming, let’s solve the following problem: Given a list of names, create a new list containing only names with at least three vowels, with the vowels in uppercase.

Imperative Approach

Let’s first tackle this problem using an imperative approach in Kotlin:

| |

Now, let’s analyze our imperative solution considering some crucial development factors:

Efficiency: This approach demonstrates optimal memory usage and performs well in Big O analysis, which assesses the minimum number of comparisons required. Given that comparing characters is the most frequent operation here, we’ll analyze the number of comparisons. Let’s assume ’n’ is the number of names and ‘k’ is the average length of each name.

- Worst-case comparisons: $n(10k)(10k) = 100nk^2$

- Explanation: $n$ (loop 1) * $10k$ (comparing each character against 10 possible vowels) * $10k$ (another

isVowel()check to decide uppercasing, again potentially comparing against 10 vowels). - Result: Since names are unlikely to exceed 100 characters, our algorithm’s time complexity is $O(n)$.

Complexity and Readability: This solution is significantly longer and more challenging to understand compared to the declarative solution we’ll examine next.

Error-Prone: The code modifies variables like

result,vowelsCount, andtransformedChar. Such mutations can introduce subtle bugs, like forgetting to resetvowelsCount. The execution flow can also become intricate, potentially leading to the omission of the crucialbreakstatement in the third loop.Maintainability: The code’s complexity and potential for errors make refactoring or modifying its behavior difficult. For instance, adapting the code to select names with three vowels and five consonants would require introducing new variables and altering loops, increasing the risk of introducing bugs.

This example highlights the potential complexity of imperative code, although refactoring it into smaller functions could improve its structure.

Declarative Approach

Now, let’s unveil the declarative solution in Kotlin:

| |

Using the same criteria for evaluating the imperative solution, let’s see how the declarative code measures up:

- Efficiency: Both imperative and declarative implementations achieve linear time complexity. However, the imperative solution is marginally more efficient due to the use of

name.count(), which counts vowels until the name’s end, even after finding three. We can address this by creating a dedicatedhasThreeVowels(String): Booleanfunction. As this solution uses the same core logic as the imperative one, the complexity analysis remains the same: $O(n)$ time. - Conciseness and Readability: The imperative solution spans 44 lines with significant indentation, while our declarative solution takes up a mere 16 lines with minimal indentation. While lines and tabs aren’t the sole indicators, a quick comparison reveals the declarative solution’s superior readability.

- Less Error-Prone: Immutability is central to this solution. We transform an initial

List<String>of all names into aList<String>containing only names with at least three vowels, followed by transforming each individualStringto have uppercase vowels. Eliminating mutation, nested loops, breaks, and relinquishing explicit control flow simplifies the code and reduces the possibility of errors. - Maintainability: The declarative code’s readability and robustness lend themselves well to refactoring. Revisiting the scenario where we need to select names with three vowels and five consonants, we can easily adapt by adding this condition to the

filter:val vowels = name.count(::isVowel); vowels >= 3 && name.length - vowels >= 5.

As an added benefit, our declarative solution is purely functional, meaning each function used is pure and free from side effects (more on purity later).

Bonus Declarative Solution

To further demonstrate the elegance of declarative programming, let’s see how this problem is solved in a purely functional language like Haskell. If you’re new to Haskell, the . operator means “after”. For instance, solution = map uppercaseVowels . filter hasThreeVowels translates to “map vowels to uppercase after filtering for names with three vowels.”

| |

This solution’s performance is comparable to our Kotlin declarative one, but with some added advantages: enhanced readability, simplicity (assuming familiarity with Haskell syntax), pure functionality, and lazy.

Key Takeaways

Declarative programming proves valuable in both FP and Reactive Programming (which we’ll cover later).

- It emphasizes defining the desired outcome (“what”) rather than specifying the exact execution steps (“how”).

- It abstracts away the program’s control flow, focusing on data transformation (e.g., $A \rightarrow B \rightarrow C \rightarrow D$).

- It promotes less intricate, more concise, and readable code that’s easier to refactor and modify. If your Android code doesn’t resemble a sentence, there might be room for improvement.

If your Android code doesn’t resemble a sentence, there might be room for improvement.

It’s worth noting that declarative programming has its limitations. There’s a possibility of ending up with inefficient code that consumes more memory and performs worse than an equivalent imperative implementation. Algorithms involving mutation, like sorting or backpropagation in machine learning, might not be the best fit for the immutable nature of declarative programming.

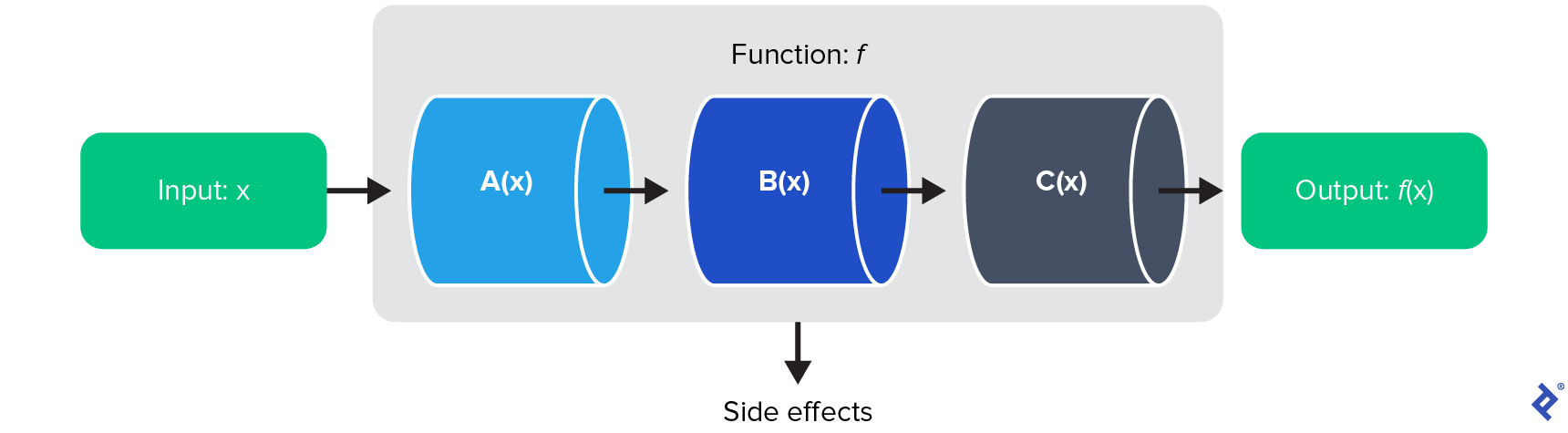

FP Element #2: Function Composition

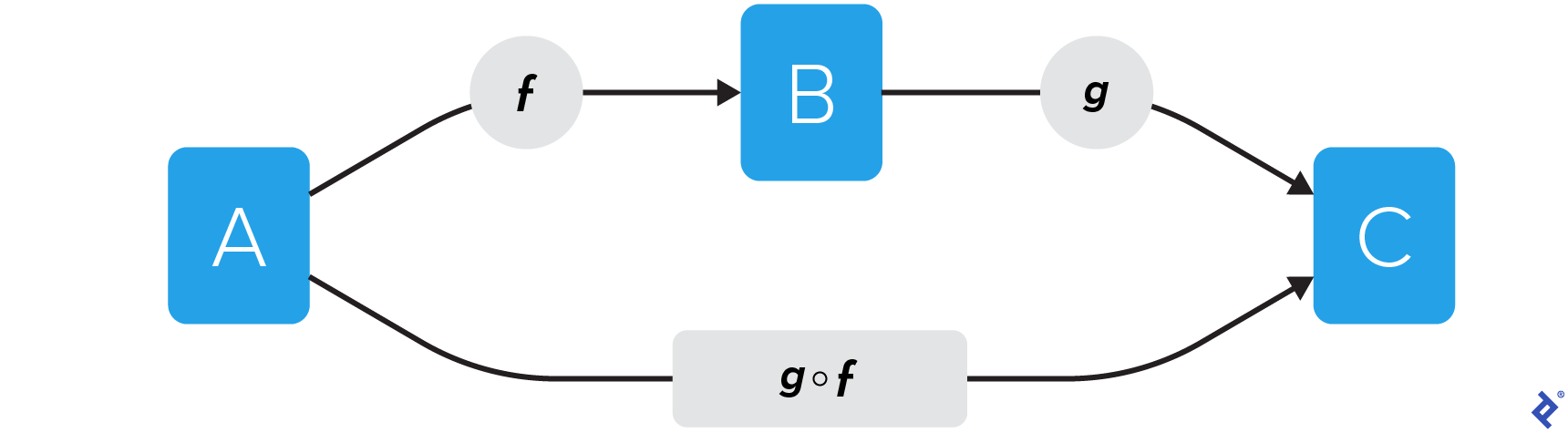

Function composition is a fundamental mathematical concept that lies at the heart of functional programming. Let’s imagine we have a function $f$ that takes $A$ as input and produces $B$ as output (represented as $f: A \rightarrow B$). We also have function $g$ that takes $B$ as input and generates $C$ as output ($g: B \rightarrow C$). We can create a new function, $h$, that directly takes $A$ and produces $C$ ($h: A \rightarrow C$). This function $h$ is essentially the composition of $g$ with $f$, often written as $g \circ f$ or $g(f())$:

Any imperative solution can be transformed into a declarative one by deconstructing the problem into smaller subproblems, solving them individually, and then piecing together these solutions using function composition to arrive at the final solution. Let’s revisit our names problem to see this in action. Breaking down the imperative solution, we have these smaller tasks:

isVowel :: Char -> Bool: Given a character (Char), determine if it’s a vowel (Bool).countVowels :: String -> Int: Given a string (String), count the number of vowels (Int).hasThreeVowels :: String -> Bool: For a given string (String), check if it contains at least three vowels (Bool).uppercaseVowels :: String -> String: Given a string (String), return a new string with vowels in uppercase.

Our declarative solution, achieved through function composition, becomes map uppercaseVowels . filter hasThreeVowels.

While this example is a bit more intricate than a straightforward $A \rightarrow B \rightarrow C$ composition, it effectively demonstrates the core principle of function composition.

Key Takeaways

Function composition is a simple yet incredibly powerful concept.

- It offers a structured approach to tackling complex problems by breaking them down into smaller, manageable steps and then merging them into a cohesive solution.

- It provides modular building blocks, allowing you to easily add, remove, or modify parts of the final solution without the risk of unintended consequences.

- The composition $g(f())$ is possible if the output type of $f$ matches the input type of $g$.

In function composition, you’re not limited to just passing data; you can pass functions as arguments to other functions, which is the essence of higher-order functions.

FP Element #3: Purity

There’s one more critical aspect of function composition that we need to discuss: purity. This concept, borrowed from mathematics, states that for a function to be considered pure, it must always produce the same output when given the same input. This consistency is fundamental to the reliability of pure functions.

Let’s illustrate this with a pseudocode example involving mathematical functions. Consider a function makeEven that doubles an integer to ensure it’s even. Our code executes the line makeEven(x) + x with an input value of x = 2. In mathematics, this calculation would consistently yield $2x + x = 3x = 3(2) = 6$. This demonstrates a pure function. However, in programming, this isn’t always guaranteed. If makeEven(x) were to modify x by doubling it before returning the result, our line would then evaluate to $2x + (2x) = 4x = 4(2) = 8$. Worse yet, the output would change with every call to makeEven.

To better understand purity, let’s delve into a couple of function types that are not considered pure:

- Partial functions: These functions aren’t defined for all possible input values. A common example is division. In programming terms, these functions often throw exceptions. For instance,

fun divide(a: Int, b: Int): Floatwould throw anArithmeticExceptionifb = 0due to division by zero. - Total functions: These functions are defined for all input values but might produce different outputs or exhibit different side effects when called with the same input. The Android ecosystem is replete with such functions, including

Log.d,LocalDateTime.now, andLocale.getDefault, to name a few.

With these definitions in mind, we can now define pure functions as total functions that are free from side effects. When you build function compositions using only pure functions, the resulting code becomes significantly more reliable, predictable, and easier to test.

Tip: You can transform a total function into a pure one by extracting its side effects and passing them as a higher-order function parameter. This approach allows for easier testing of total functions by providing mock implementations for the side effects. Here’s an example using the @SideEffect annotation from the Ivy FRP library, which we’ll explore later:

| |

Key Takeaways

Purity is the final essential element in the functional programming paradigm.

- Exercise caution with partial functions—they can lead to app crashes.

- Composing total functions can introduce unpredictable behavior due to their potential for side effects.

- Strive to write pure functions whenever possible. You’ll reap the benefits of increased code stability and maintainability.

With our exploration of functional programming complete, let’s shift our attention to reactive programming, another cornerstone of future-proof Android development.

Reactive Programming 101

Reactive programming is a declarative programming paradigm where the program focuses on reacting to data or event changes rather than actively polling for them.

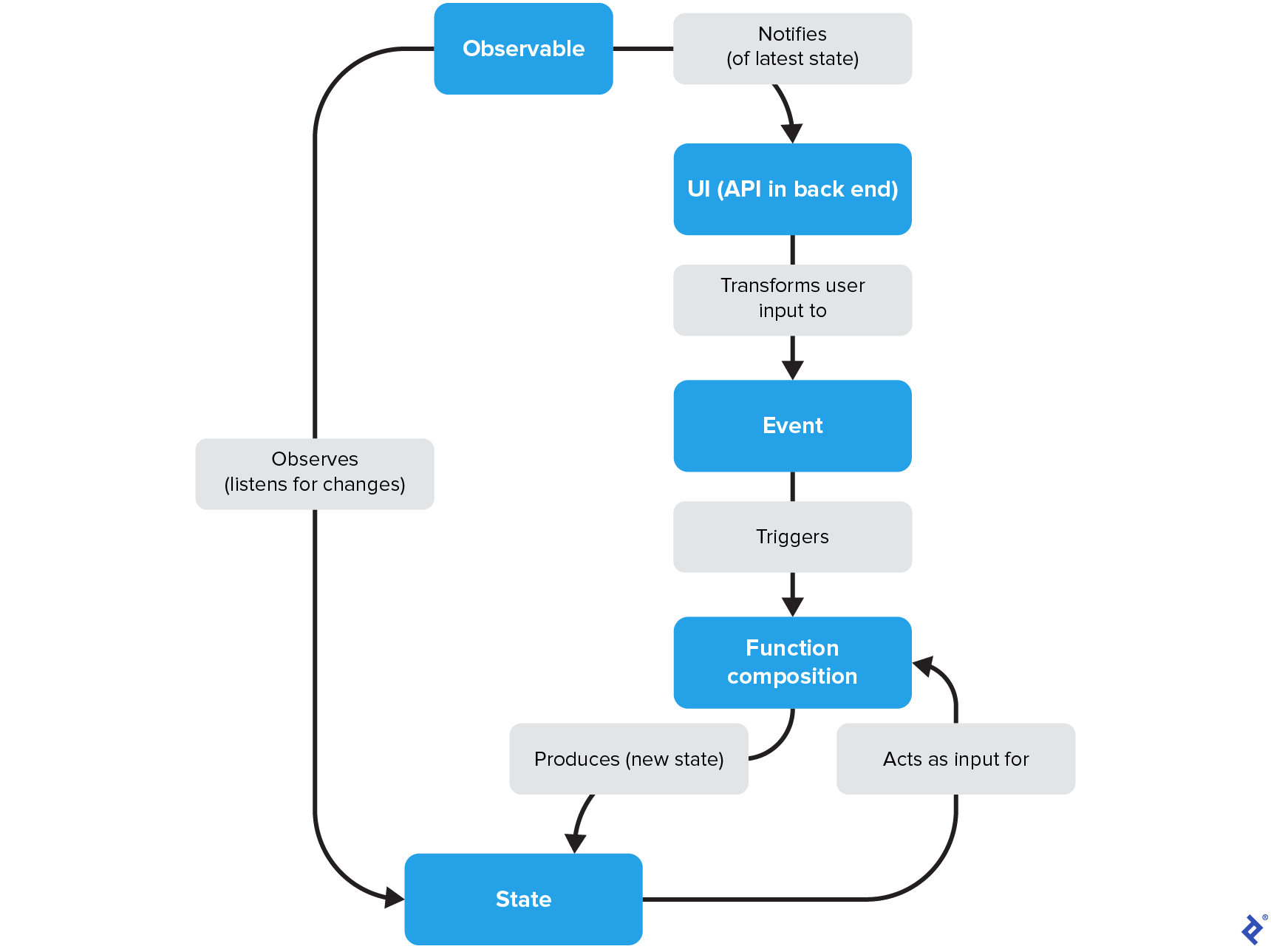

A typical reactive programming cycle involves these key components: events, the declarative pipeline, states, and observables:

- Events: These are signals from the external world, often user interactions or system events, that initiate updates within the application. Events essentially convert these signals into inputs for the processing pipeline.

- Declarative Pipeline: This is a chain of composed functions that takes an

(Event, State)pair as input and transforms it into a newStateas output:(Event, State) -> f -> g -> … -> n -> State. Pipelines must operate asynchronously to handle concurrent events without blocking other processes or waiting for their completion. - States: The state represents the current snapshot of your application’s data model at a given time. The application’s domain logic uses this state to determine the next desired state and perform the necessary updates.

- Observables: Observables are responsible for monitoring state changes and notifying any interested parties (subscribers) about these updates. In Android development, observables are commonly implemented using frameworks like

Flow,LiveData, orRxJava. Their primary role is to update the user interface (UI) whenever the state changes, allowing it to react accordingly.

There are numerous definitions and implementations of reactive programming. Here, we’ve taken a pragmatic approach tailored to applying these concepts in real-world projects.

Connecting the Pieces: Functional Reactive Programming

Functional and reactive programming, each powerful in their own right, transcend the fleeting relevance of libraries and APIs, equipping you with enduring programming skills.

Furthermore, the true potential of these paradigms is unlocked when they are combined. Now that we have a solid grasp of functional and reactive programming, let’s explore their fusion. In part 2 of this tutorial, we’ll define functional reactive programming (FRP) in detail and implement it in a sample Android application using appropriate libraries.

The Toptal Engineering Blog expresses gratitude to Tarun Goyal for reviewing the code samples included in this article.

![A top diagram has three blue "[String]" boxes connected by arrows pointing to the right. The first arrow is labeled "filter has3Vowels" and the second is labeled "map uppercaseVowels." Below, a second diagram has two blue boxes on the left, "Char" on top, and "String" below, pointing to a blue box on the right, "Bool." The arrow from "Char" to "Bool" is labeled "isVowel," and the arrow from "String" to "Bool" is labeled "has3Vowels." The "String" box also has an arrow pointing to itself labeled "uppercaseVowels."](https://assets.toptal.io/images?url=https%3A%2F%2Fbs-uploads.toptal.io%2Fblackfish-uploads%2Fpublic-files%2Fimage_2-05a7c998a806e858d12f8efc44d195a8.png)