A system for recommending items, often called a recommendation engine, enables algorithm creators to predict user preferences from a set of options. Unlike search bars, these engines help users discover items they might not have found otherwise, making them valuable for platforms like Facebook, YouTube, and Amazon.

Two common approaches power recommendation engines. One analyzes the characteristics of items a user likes to suggest similar ones. The other leverages the preferences of other users, calculating similarity scores to recommend items accordingly. These methods can also be combined for a more robust engine. However, choosing an algorithm suitable for the specific problem remains crucial.

This tutorial guides you through building a collaborative, memory-based recommendation engine using basic set operations, math, and Node.js/CoffeeScript. This engine, similar to the second approach mentioned earlier, will suggest movies based on user likes and dislikes. The complete source code is available here.

Sets and Equations

Before diving into implementation, let’s understand the underlying concept. Our engine treats items and users as simple identifiers, disregarding additional item attributes. User similarity is represented by a similarity index, a decimal between -1.0 and 1.0. Similarly, the likelihood of a user liking a movie is expressed as a decimal within the same range.

Our algorithm employs various sets: sets of movies liked and disliked by each user, and sets of users who liked or disliked each movie. Unions and intersections of these sets, along with ordered lists of suggestions and similar users, are generated during recommendation.

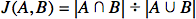

To quantify similarity, we’ll use a modified Jaccard index, originally called “coefficient de communauté” by Paul Jaccard. This formula compares two sets, producing a statistic between 0 and 1.0:

It divides the count of shared elements by the total element count in both sets (counting each element only once). Identical sets have a Jaccard index of 1, while sets with no shared elements result in 0.

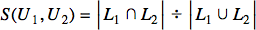

To compare users, we treat them as identifiers with liked and disliked movie sets. If we focused solely on liked movies, the Jaccard index would suffice:

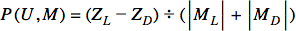

Here, U1 and U2 represent the users, while L1 and L2 represent their respective sets of liked movies. However, shared dislikes also indicate similarity, leading to a modification:

We now include shared dislikes in the numerator and consider all liked or disliked items in the denominator.

Furthermore, we must account for opposing preferences. Users with opposite tastes shouldn’t have a similarity index of 0:

This extended formula subtracts conflicting likes and dislikes from shared ones, resulting in a range of -1.0 to 1.0. Identical preferences yield 1.0, while completely opposing tastes result in -1.0.

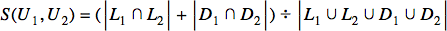

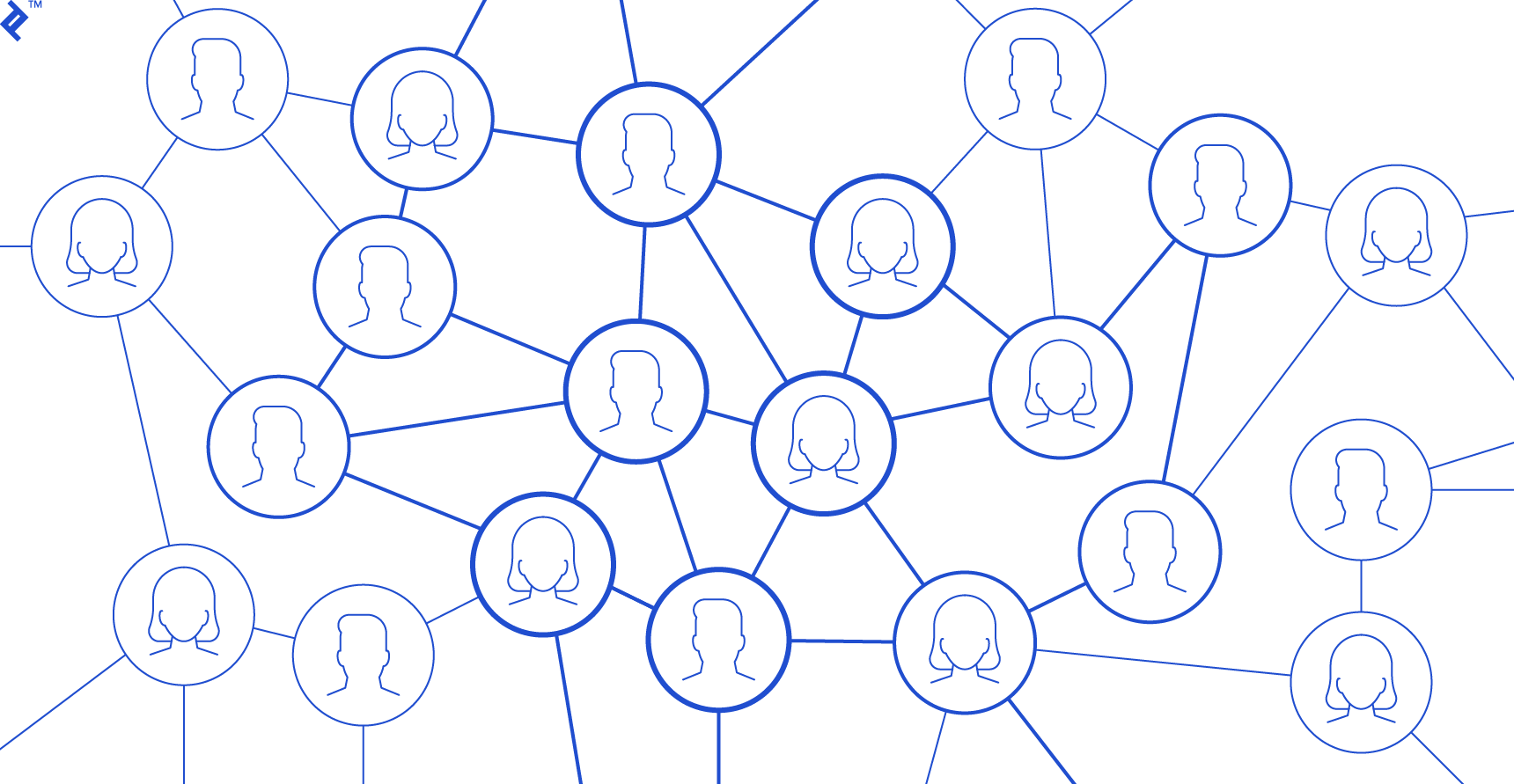

Before implementing our engine, let’s examine one more formula:

This formula calculates the probability (P(U,M)) of user U liking movie M. ZL and ZD represent the sum of similarity indices between U and users who liked or disliked M, respectively. |ML|+|MD| denotes the total number of users who rated M. The result falls between -1.0 and 1.0.

With these formulas, we can start building our recommendation engine.

Building the Recommendation Engine

We’ll create a simple Node.js application with a basic HTML/Bootstrap frontend. The backend, written in CoffeeScript, will handle GET and POST requests. While users exist, we won’t implement complex registration or login mechanisms. We’ll use the Bourne package for persistency, storing data in JSON files, and Express.js to manage routes and handlers.

If you’re new to Node.js, cloning the GitHub repository might be helpful. As with any Node.js project, we begin by creating a package.json file and installing dependencies listed in the “package.json” file (execute “$ npm install”).

Required Node.js packages:

We’ll structure the engine with four CoffeeScript classes under “lib/engine”: Engine, Rater, Similars, and Suggestions. Engine provides a unified API, binding the other three. Rater tracks likes and dislikes (two separate instances). Similars and Suggestions handle similar user calculations and recommended items, respectively.

Tracking Likes and Dislikes

Let’s start with the Rater class:

| |

We’ll have separate instances for likes and dislikes. “Rater#add()” records user preferences, while “Rater#remove()” removes them.

Using Bourne, ratings are stored in “./db-#{@kind}.json” (“likes” or “dislikes”). The database is opened when instantiating Rater:

| |

This simplifies adding ratings:

| |

Removing ratings is similar (“db.delete” replaces “db.insert”). We’ll check for existing entries before adding or removing. After updates, we’ll recalculate similarity indices and generate new suggestions. The “Rater#add()” and “Rater#remove()” methods resemble:

| |

For simplicity, error handling is omitted here, but it’s crucial in real-world code.

The remaining methods, “Rater#itemsByUser()” and “Rater#usersByItem()”, retrieve items rated by a user and users who rated an item, respectively. For instance, when Rater is instantiated with kind = “likes”, “Rater#itemsByUser()” returns items the user liked.

Finding Similar Users

Next is the Similars class, responsible for computing and tracking similarity indices. It utilizes Rater instances to fetch rated items and calculates the index using our formula.

Similar to Rater, data is stored in “./db-similars.json”, opened during instantiation. The “Similars#byUser()” method retrieves users similar to a given user:

| |

The core method, “Similars#update()”, takes a user as input, computes similar users, and stores them with their indices. It begins by retrieving the user’s likes and dislikes:

| |

Then, it identifies users who rated these items:

| |

Finally, it calculates and stores the similarity index for each user pair:

| |

The code snippet above incorporates our Jaccard index variant for calculating similarity.

Generating Recommendations

The Suggestions class handles predictions. It utilizes a Bourne database (“db-suggestions.json”) opened during construction.

The “Suggestions#forUser()” method retrieves computed suggestions:

| |

The “Suggestions#update()” method, similar to “Similars#update()”, takes a user as input. It retrieves similar users and unrated items:

| |

Then, it iterates through each item, calculating the likelihood of the user liking it based on existing data:

| |

The updated recommendations are saved back to the database:

| |

Exposing the Library API

The Engine class combines these components into a user-friendly API:

| |

After instantiating an Engine object:

| |

We can manage likes and dislikes:

| |

And update similarity indices and suggestions:

| |

Finally, we export the Engine class and other classes from their respective “.coffee” files:

| |

Then, we export Engine from the package by creating an “index.coffee” file containing:

| |

Creating the User Interface

To interact with the engine, we’ll build a simple web interface. Our “web.iced” file will spawn an Express app and handle routes:

| |

The app handles four routes. The index route ("/") serves the frontend HTML, rendering a Jade template using movie data, username, user preferences, and top suggestions. The template source code is available in the GitHub repository.

The “/like” and “/dislike” routes handle POST requests for recording user preferences, removing conflicting ratings if necessary (e.g., liking a previously disliked item). Users can also “unlike” or “un-dislike” items.

Lastly, the “/refresh” route triggers recommendation regeneration on demand, although this happens automatically after each rating.

Test-drive

To test the application, create a “data/movies.json” file containing movie data:

| |

You can copy the pre-populated example from GitHub repository.

Once everything is set up, start the server:

| |

If successful, you should see:

| |

The prototype relies on a chosen username (visit “http://localhost:5000”) due to the lack of user authentication. After submitting a username, you’ll be redirected to a page with “Recommended Movies” and “All Movies” sections. Initially, recommendations won’t appear due to the lack of data.

Open another browser window, access “http://localhost:5000”, and log in as a different user. Rate some movies, including a few rated by the first user. Return to the first user’s window and rate movies as well. Once both users have rated common items, recommendations should appear.

Improvements

Our prototype engine has room for improvement, especially for large-scale use. While robust solutions already exist, this section highlights areas for enhancement, focusing on conceptual aspects rather than specific implementation details.

Using a real database like Redis instead of our file-based solution is crucial for scalability. Redis’s speed and special capabilities make it suitable for managing set-like data.

Instead of recalculating recommendations in real-time after each rating, we can queue updates and process them in the background, potentially on a timed interval.

Strategically selecting a subset of users for recommendation generation can enhance performance. For instance, in a restaurant recommendation engine, limiting similar users to those in the same geographical area can be beneficial.

Adopting a hybrid approach, combining collaborative and content-based filtering, can improve accuracy. Platforms like Netflix use this strategy, considering both user behavior and movie attributes.

Conclusion

Collaborative memory-based recommendation engines are powerful tools. Our simple prototype demonstrates the fundamental concepts behind them. While not perfect, it lays the groundwork for more sophisticated implementations like Recommendable.

Like many data-driven problems, achieving accurate recommendations hinges on selecting the right algorithms and utilizing relevant content attributes. Hopefully, this article has shed light on the inner workings of collaborative memory-based recommendation engines.