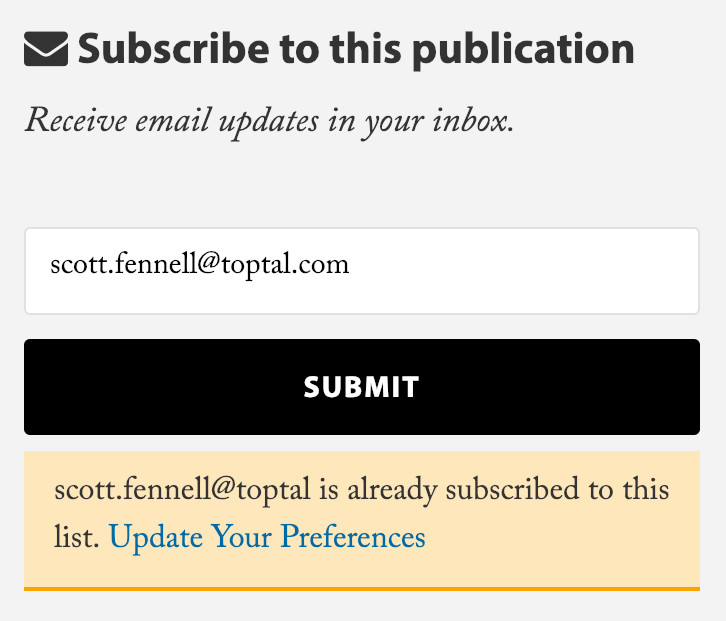

Enhancing your reputation as a WordPress developer, at least from a client’s perspective, can be effectively achieved by mastering API consumption. Let’s consider a common scenario in WordPress API implementation: You’re asked by your client to integrate an email subscription widget into their site. You find some code from their chosen third-party email provider – maybe a script tag or an iframe – embed it into the page, and proudly declare to your client, “All set!”

However, this time you’re dealing with a more meticulous client who points out several issues:

- The widget’s font, while sans-serif like the rest of the site, isn’t consistent. It uses Helvetica instead of the custom font you implemented.

- Clicking the widget’s subscription form leads to a full page reload, which disrupts the flow, especially if the widget is placed mid-article.

- There’s a noticeable delay in the widget’s loading time compared to the rest of the page, giving it a clunky and unprofessional feel.

- The client wants subscribers to be tagged with metadata related to the specific post from which they subscribed, a feature absent in the current widget.

- Managing two separate dashboards (wp-admin and the email service’s admin area) is inconvenient for the client.

Now, you have two options. You could either dismiss these points as “nice-to-haves” and highlight the advantages of a simple 80/20 solution to your client, or you could take on the challenge and address their concerns. My experience has shown that fulfilling such requests – proving your proficiency in handling third-party services – effectively convinces clients of your WordPress expertise. Plus, it’s often an enjoyable challenge.

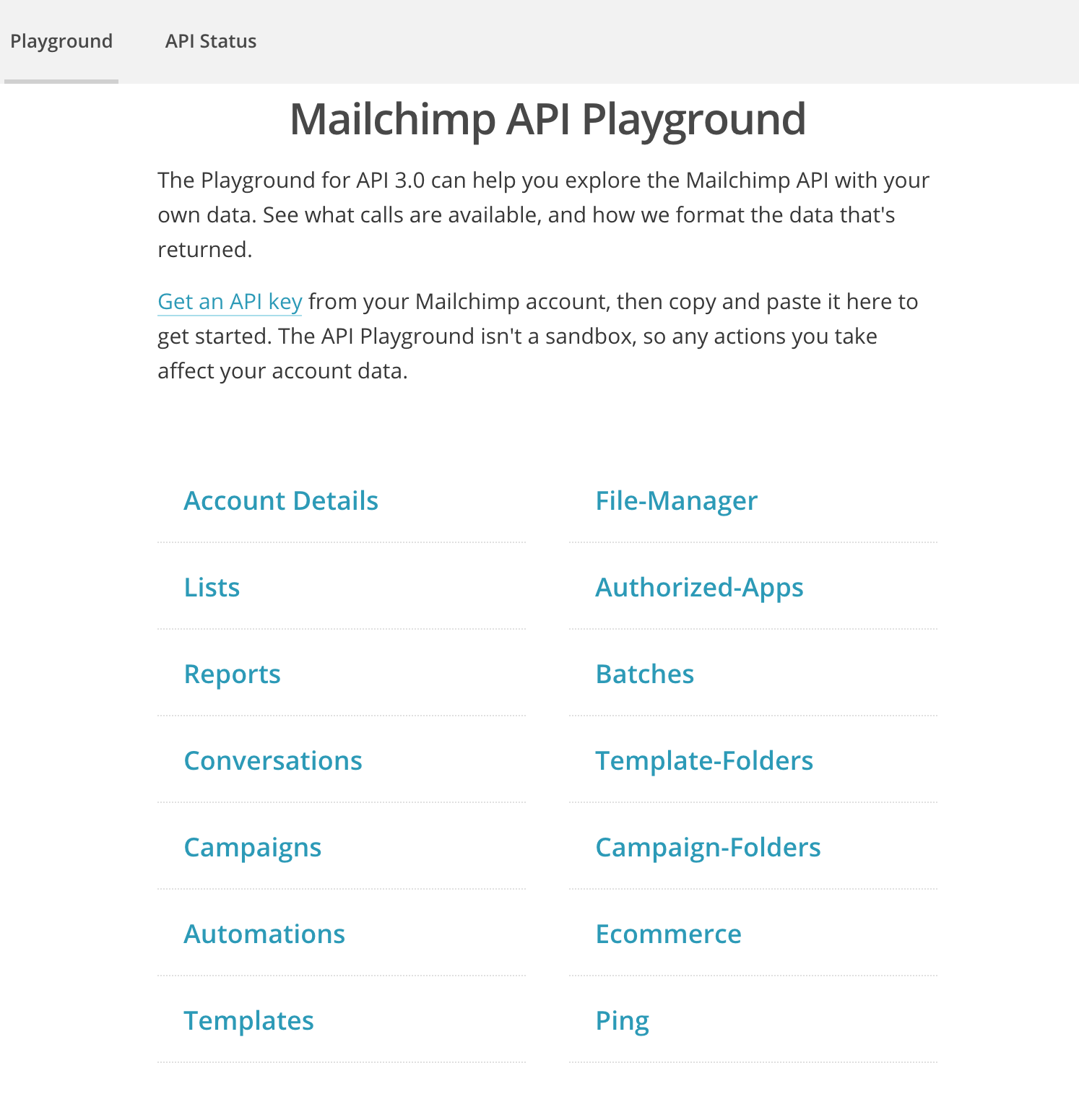

Over the past ten years, I’ve utilized WordPress to consume APIs from around 50 different services. Some of the most frequent ones include MailChimp, Google Analytics, Google Maps, CloudFlare, and Bitbucket. But what if you need to go beyond pre-built solutions and create a custom solution?

Developing a WordPress API Client

In this article, we’ll focus on building against a generic “email service” API, aiming for a platform-agnostic approach. We’ll assume we’re working with a JSON REST API, which is a common architecture. Here are some related concepts that might be helpful to understand the technical aspects discussed:

- The WordPress HTTP family of functions

- JSON

- REST

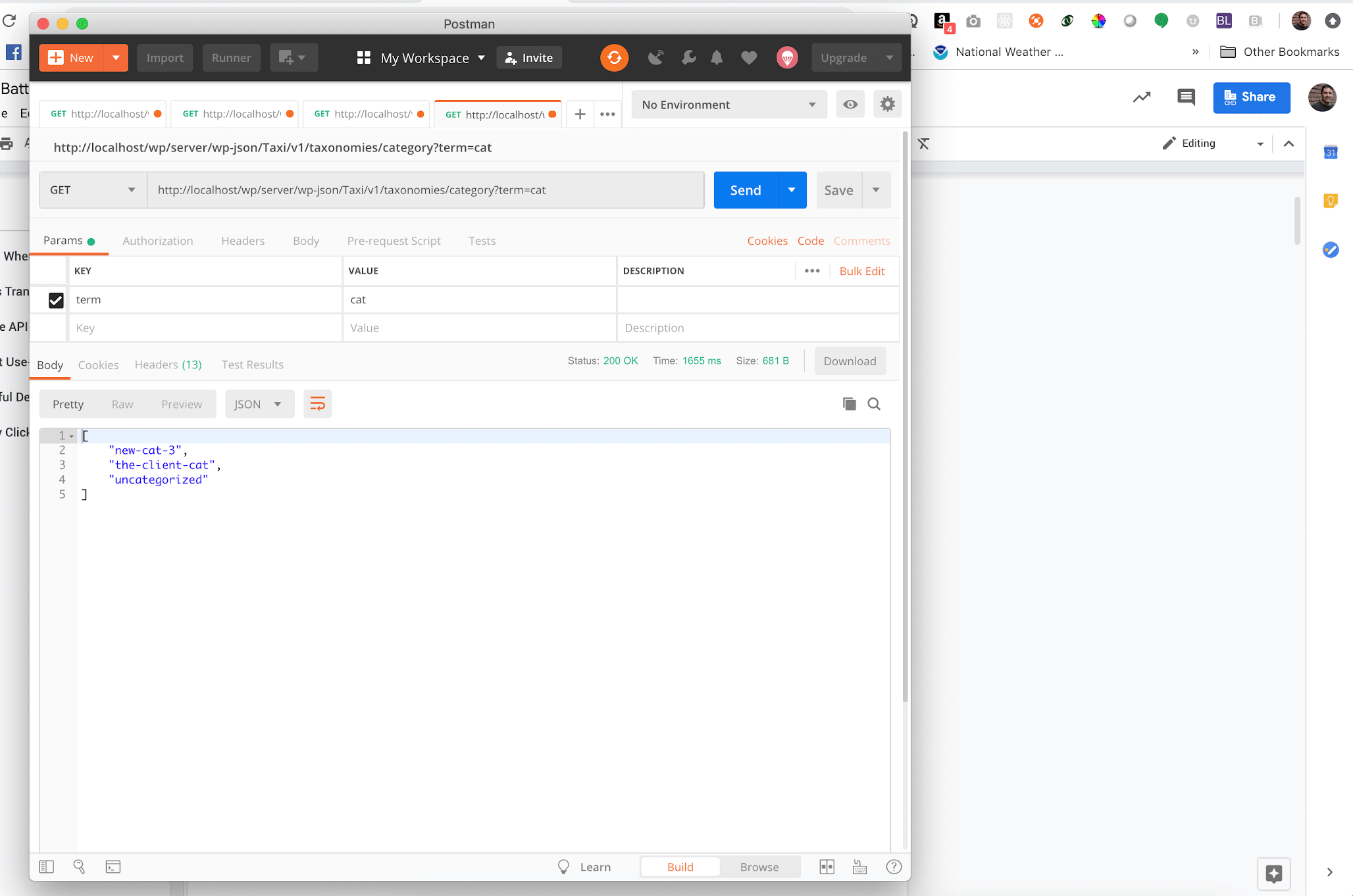

If you have a basic understanding of these concepts and wish to delve deeper, I encourage you to download the excellent Postman application. This tool allows interaction with APIs without writing code.

Even if you’re unfamiliar with these concepts, I encourage you to continue reading. While a technical audience with some WordPress knowledge will benefit the most from this article, I’ll make sure to explain the significance of each technique in a more accessible manner. This way, even non-technical readers will be able to evaluate the return on investment of each point before approving it and assess the quality of the implementation afterward.

Note: For a quick refresher, refer to our WordPress REST API guide.

Without further ado, let’s dive into several techniques that I find valuable across various APIs, projects, and teams I’ve worked with.

Transient Data: When to Cache, When to Discard

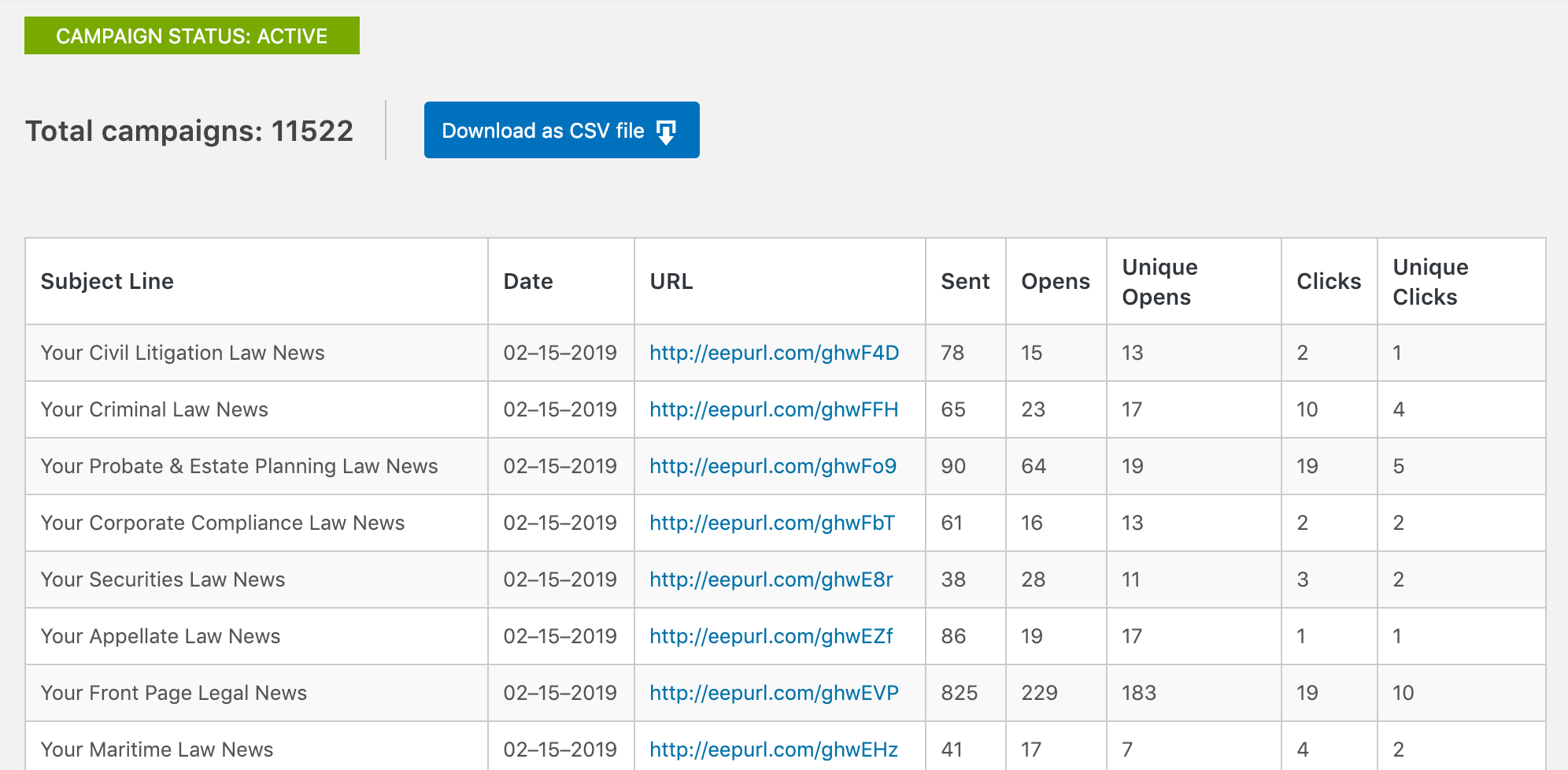

Earlier, we mentioned the client’s frustration with juggling two admin areas: wp-admin and the email service’s dashboard. A good solution would be a dashboard widget within wp-admin that displays a summary of recent subscriber activity.

However, this approach could potentially lead to numerous HTTP requests to the remote API (provided by the email service), causing slow page loading times. To enhance performance, we can cache API calls using transients. This Codex article offers a comprehensive explanation that I highly recommend reading. To summarize:

- Retrieve data from the remote API.

- Store it using

set_transient()with an appropriate expiration time. Consider factors such as performance, rate limits, and the acceptable margin of error for displaying outdated data in this specific context. - Continue with your business logic – process the data, return a value, or perform other necessary operations.

- When the data is required again (e.g., on the next page load), check for its presence in the transient cache using

get_transient()before making another API call.

While this is a solid and effective foundation, we can further optimize it by considering REST verbs. Of the five common methods (GET, POST, PATCH, PUT, DELETE), only one is suitable for transient caching – GET.

In my plugins, I typically dedicate a PHP class to abstract calls to the relevant remote API. When instantiating this class, the HTTP method is passed as an argument. If it’s not a GET request, the caching layer is bypassed entirely.

Moreover, non-GET calls suggest data modification on the remote server, such as adding, editing, or removing an email subscriber. In these cases, it’s prudent to invalidate the existing cache for that resource using delete_transient().

Let’s apply this to our WordPress email subscription API example:

- A dashboard widget showing recent subscribers will access the

/subscribersendpoint via a GET request. Being a GET request, the result is cached as a transient. - A sidebar widget for email subscriptions will call the

/subscribersendpoint with a POST request. Since it’s a POST request, it not only bypasses the transient cache but also triggers the deletion of the relevant portion of the cache to reflect the new subscriber in the dashboard widget. - When naming transients, I often use the remote API URL being called, which makes identifying the correct transient for deletion straightforward. For endpoints with arguments, I concatenate and append them to the transient name.

As a client or non-technical stakeholder, it’s crucial to request transient caching – or at least a discussion about it – whenever an application fetches data from an external service. Familiarize yourself with the excellent Query Monitor plugin to understand how transients work. It provides an interface to view cached data, frequency of access, and expiration times.

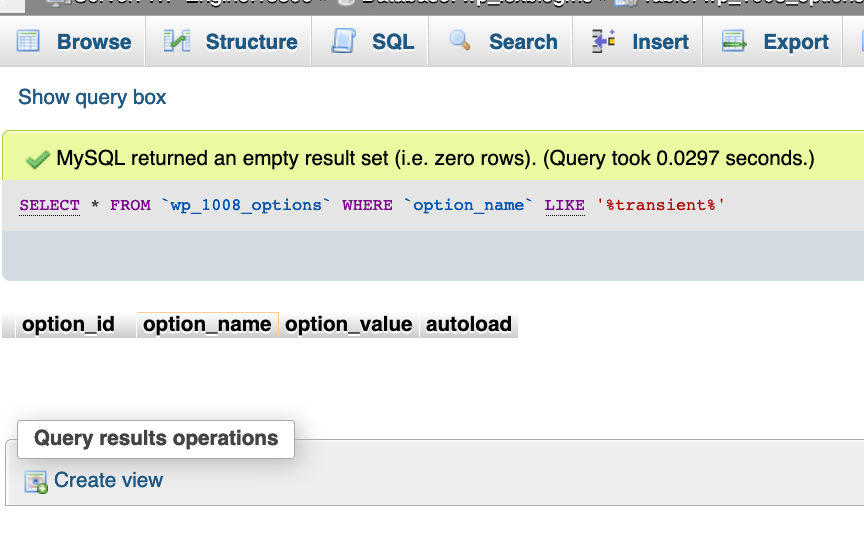

Beyond Transient Caching

Some premium WordPress hosting providers restrict the use of transients in production environments. They might have code, potentially in the form of an MU plugin or other scripts, that intercepts attempts to use the transients API and store the data using the object cache instead. WP-Engine, in its typical configuration, is a classic example.

If your operations primarily involve data storage and retrieval, this might not be noticeable or require any action. The family of *_transient() functions will yield the same outcome, simply utilizing the object cache instead of the transient cache. However, challenges arise when attempting to delete transients.

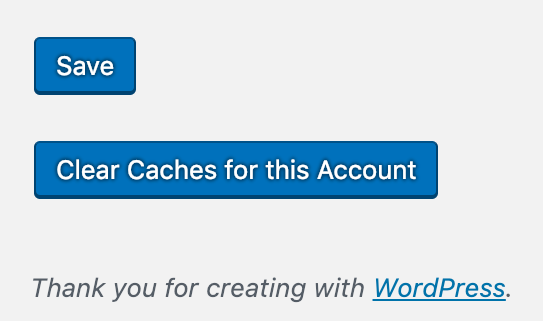

If your API integration is complex enough to warrant a dedicated settings page, you might want to include a UI element that lets admin users clear the entire transient cache for your plugin. This is particularly useful when the client modifies data directly on the remote service and needs to invalidate the cached data in WordPress. This button can also be helpful if the client changes account credentials or API keys, or as a general “reset” button for debugging.

Even if you’ve diligently namespaced your transient keys to facilitate identification for delete_transient(), the ideal solution might still involve raw SQL, which should be avoided in WordPress:

| |

This approach is neither convenient nor efficient. Instead, object caching becomes a better choice because it allows for convenient grouping of cached values. This way, clearing all cached data associated with your plugin becomes a simple one-liner call to wp_cache_delete( $key, $group ).

To summarize: Mastering API consumption requires proficiency in managing the cache for the retrieved data.

For clients, a crucial aspect to monitor is any inconsistent cache behavior between staging and production environments. While testing new features in staging is essential, caching requires equally thorough testing in production.

Shaping Your PHP Class Hierarchy Based on API Structure

When designing PHP classes for my plugin, I find it beneficial to mirror the structure of the API endpoints. For instance, what do these endpoints have in common:

- https://api.example-email-service.com/v1/subscribers.json

- https://api.example-email-service.com/v1/lists.json

- https://api.example-email-service.com/v1/campaigns.json

They all return collections – a GET request response containing zero or more results in an array. While seemingly obvious, this observation guides the following class structure in my PHP code:

class.collection.php, an abstract classclass.subscribers.phpextending theCollectionabstract class.class.lists.phpextending theCollectionabstract class.class.campaigns.phpextending theCollectionabstract class.

The abstract class would accept an array of query parameters as its argument: elements like pagination, sort column, sort order, and search filters. It would include methods for common tasks such as making API calls, error handling, and potentially transforming the results into an HTML <select> menu or a jQueryUI AutoSuggest. The classes instantiating this abstract class could be concise, perhaps only defining the string used in the *.json API endpoint URL.

Similarly, what’s the common thread among these endpoints:

- https://api.example-email-service.com/v1/subscribers/104abyh4.json

- https://api.example-email-service.com/v1/lists/837dy1h2.json

- https://api.example-email-service.com/v1/campaigns/9i8udr43.json

They all return an item – a single, specific element from a collection. Examples include a particular email subscriber, a single email list, or one specific email campaign. This pattern leads to the following structure in the PHP code:

class.item.php, an abstract classclass.subscriber.phpextending theItemabstract class.class.list.phpextending theItemabstract class.class.campaign.phpextending theItemabstract class.

This abstract class would take a string as its argument, representing the specific item requested. Again, the instantiated classes could be minimal, potentially only specifying the string used in */duy736td.json.

While numerous approaches exist for class inheritance, the remote API’s structure can often inform and guide the application’s structure.

As a client, a telltale sign of subpar architecture is the need to request the same change repeatedly across the application. For example, if you request reports to display 100 results per page instead of 10, and you have to reiterate this request for subscriber reports, campaign reports, unsubscribe reports, etc., it might indicate poor class design. Consider inquiring about the benefits of refactoring – a process that focuses on improving the underlying codebase without altering functionality to facilitate easier future modifications.

Leveraging WP_Error Effectively

It took me longer than I’d like to admit to fully appreciate and utilize the WP_Error family of functions in my code. I often took shortcuts, either assuming errors wouldn’t occur or handling them on a case-by-case basis. Working with remote APIs changed that, as it presented a perfect scenario for utilizing WP_Error.

Remember the PHP class responsible for making HTTP requests to the remote API? At its core, this class boils down to calling wp_remote_request() to retrieve an HTTP response object from the API. If the call fails, wp_remote_request() conveniently returns a WP_Error object. But what about successful calls that return an unfavorable HTTP response?

For instance, imagine calling the /lists.json endpoint for an account without any lists configured. This scenario would result in a valid HTTP response but with a 400 status code. While not a fatal error, from the perspective of front-end code attempting to populate a dropdown menu, a 400 response is as good as a WSOD! To address this, I perform additional parsing on the result of wp_remote_request(), potentially returning a WP_Error:

| |

This pattern simplifies the code that calls our API class, as we can reliably use is_wp_error() before processing the output.

As a client, it’s helpful to occasionally assume the roles of a malicious user, a confused user, and an impatient user. Interact with the application in unexpected ways – do things your developers might not expect. Observe the outcomes. Do you encounter helpful error messages? Are there any error messages at all? If not, it might be worthwhile to invest in improving error handling.

The Power of ob_get_clean() for Debugging

The interconnected nature of the modern web, where almost every site consumes external APIs and often exposes its own, presents both opportunities and challenges. This interconnectedness can sometimes lead to performance bottlenecks.

Remote HTTP requests are often the most time-consuming part of loading a page. As a result, many API-driven components execute either via Ajax or scheduled tasks (cron). For example, an autosuggest feature for searching through email subscribers should ideally query the remote data source dynamically with each keystroke rather than loading all 100,000 subscribers into the DOM on page load. If that’s not feasible, a bulk query could synchronize data via a nightly cron job, allowing results to be fetched from a local cache instead of the remote API.

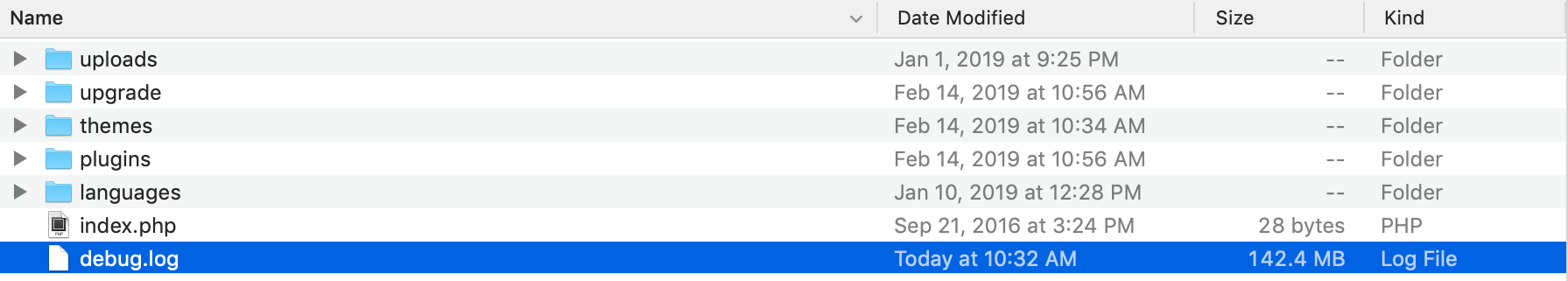

However, this approach complicates debugging. Instead of relying on WP_DEBUG and inspecting error messages in the browser console, you’re left examining network logs or tailing log files during cron task execution. This can be inconvenient.

One way to improve this is through strategic use of error_log(). However, excessive logging can lead to large, unwieldy log files, making monitoring and analysis difficult. Therefore, it’s crucial to be selective with logging, putting as much thought into it as the application logic itself. Logging an obscure edge-case error that occurs infrequently on a cron task is useless if the real issue remains elusive because you forgot to log a specific array member or value.

My approach is to log comprehensively when necessary: don’t log everything, but when you do, log everything relevant. In other words, when dealing with a problematic function, I log as much information as possible:

| |

This essentially means using var_dump() to output the entire problematic value into a single log entry.

As a client, it’s advisable to periodically check the overall file storage used by your application. A sudden increase in storage consumption could indicate an issue with excessive logging. Investing in better logging practices will benefit both your developers and your users!

Concluding Thoughts

While the listicle structure of this article might not be ideal, I couldn’t find a more unifying theme for these patterns. These concepts are broadly applicable to any JSON REST endpoint and any WordPress output.

These patterns consistently emerge regardless of the specific remote API or its purpose within WordPress. I’ve consolidated these principles into a plugin boilerplate that significantly streamlines my workflow. Do you have any similar techniques that you find valuable across projects? Please share them!