When we encounter the term “text search,” we typically envision a vast collection of text that is structured to enable rapid retrieval of one or more search terms provided by a user. This represents a fundamental challenge for computer scientists, leading to numerous solutions.

However, consider the reverse scenario: What if we need to index a set of search phrases in advance, and only during execution is a large text body presented for searching? This is the core focus of this trie data structure tutorial.

Applications

A practical illustration of this scenario involves matching numerous medical theses against a list of medical conditions to identify which theses address which conditions. Another example is analyzing a vast collection of judicial precedents to extract referenced laws.

Direct Approach

The simplest method involves iterating through each search phrase and searching the entire text for each phrase sequentially. However, this approach lacks scalability. Searching for a string within another has a complexity of O(n). Repeating this process for m search phrases results in an unfavorable complexity of O(m * n).

The primary (and perhaps only) advantage of a direct approach lies in its ease of implementation, as demonstrated in the following C# code snippet:

| |

Executing this code on my development machine [1] using a test dataset [2] yielded an execution time of 1 hour and 14 minutes – significantly longer than what one would need for a coffee break or a quick stretch.

A Better Approach - The Trie

We can improve the previous scenario in several ways. One option is to partition the search process and parallelize it across multiple processors/cores. However, the reduction in runtime achieved through this approach (approximately 20 minutes assuming perfect distribution across 4 processors/cores) may not justify the increased coding and debugging complexity.

The ideal solution would involve traversing the text body only once. This necessitates indexing the search phrases in a structure that allows linear traversal, concurrent with the text body, in a single pass, achieving a final complexity of O(n).

A data structure particularly well-suited for this scenario is the trie. Often overlooked, the trie is a versatile data structure that proves invaluable for search problems.

A previous Toptal tutorial on tries provides a comprehensive introduction to their structure and usage. In essence, a trie is a specialized tree capable of storing a sequence of values, enabling the retrieval of a valid subset of that sequence by tracing the path from the root to any node.

By combining all search phrases into a single trie, where each node represents a word, we effectively organize the phrases in a structure that allows us to generate a valid search phrase by simply traversing from the root downwards along any path.

Tries excel at reducing search time. To illustrate this using a simplified example, consider a binary tree. Traversing a binary tree has a complexity of O(log2n) because each node branches into two, halving the remaining traversal path. Similarly, a ternary tree has a traversal complexity of O(log3n). In a trie, however, the number of child nodes depends on the sequence it represents. For meaningful text, the number of children is typically high.

Text Search Algorithm

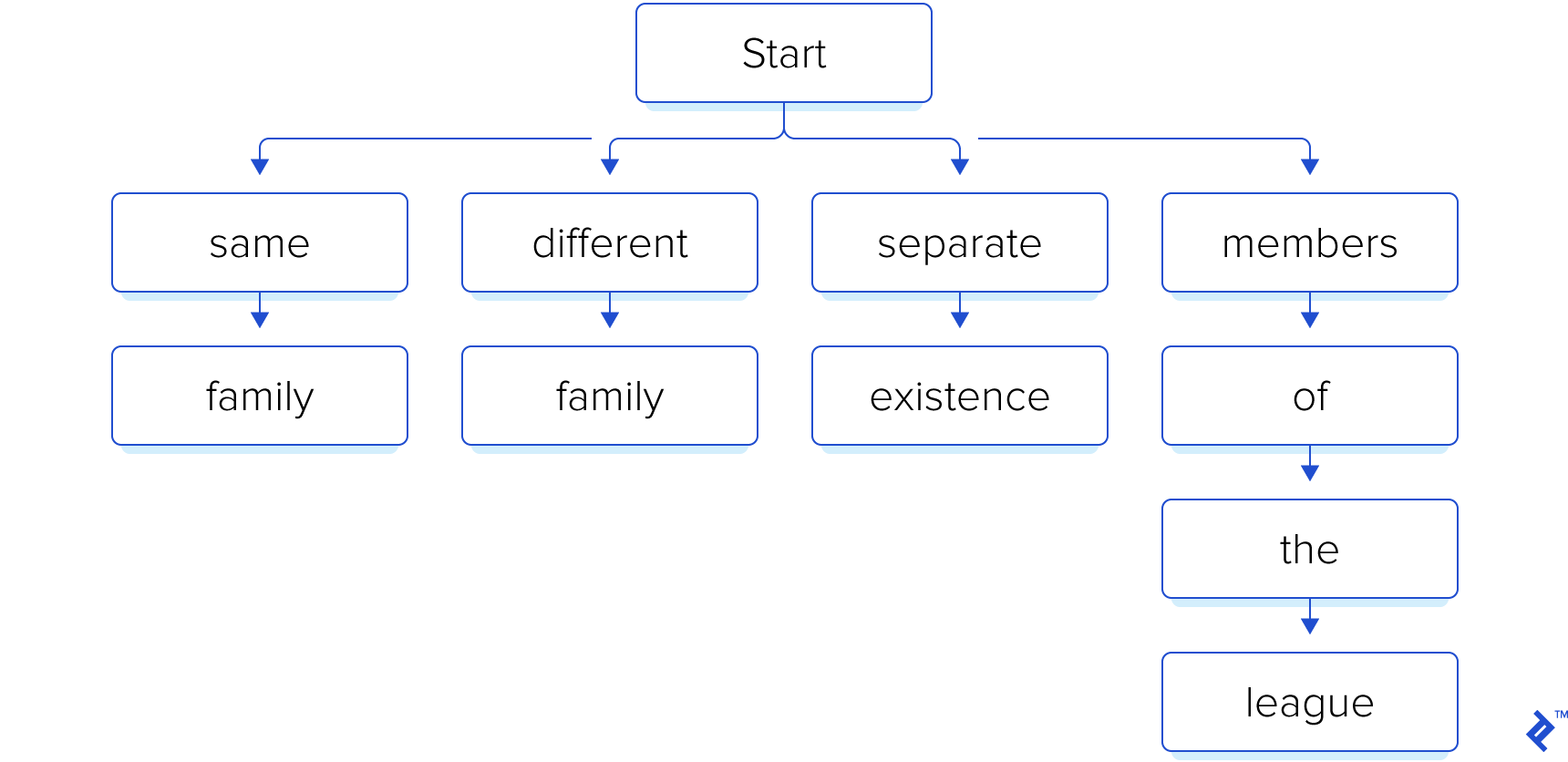

Let’s consider a simple example with the following search phrases:

- “same family”

- “different family”

- “separate existence”

- “members of the league”

Since we know our search phrases beforehand, we begin by constructing an index in the form of a trie:

Subsequently, let’s assume the user provides our software with a file containing the following text:

The European languages are members of the same family. Their separate existence is a myth.

The remaining process is straightforward. Our algorithm employs two indicators (or pointers), one positioned at the root or “start” node of our trie structure and the other at the first word of the text body. Both indicators move synchronously, word by word. The text indicator advances linearly, while the trie indicator traverses the trie depth-wise, following a path of matching words.

The trie indicator returns to the start node in two scenarios: upon reaching the end of a branch, indicating a successful search phrase match, or upon encountering a word mismatch, signifying an unsuccessful match.

The text indicator deviates from its linear movement when a partial match occurs, meaning a mismatch is encountered after a series of matches before reaching the end of a branch. In this case, the text indicator remains stationary as the last word could mark the beginning of a new branch.

Applying this algorithm to our trie data structure example yields the following results:

| Step | Trie Indicator | Text Indicator | Match? | Trie Action | Text Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | start | The | - | Move to start | Move to next |

| 1 | start | European | - | Move to start | Move to next |

| 2 | start | languages | - | Move to start | Move to next |

| 3 | start | are | - | Move to start | Move to next |

| 4 | start | members | members | Move to members | Move to next |

| 5 | members | of | of | Move to of | Move to next |

| 6 | of | the | the | Move to the | Move to next |

| 7 | the | same | - | Move to start | - |

| 8 | start | same | same | Move to same | Move to next |

| 9 | same | family | family | Move to start | Move to next |

| 10 | start | their | - | Move to start | Move to next |

| 11 | start | separate | separate | Move to separate | Move to next |

| 12 | separate | existence | existence | Move to start | Move to next |

| 13 | start | is | - | Move to start | Move to next |

| 14 | start | a | - | Move to start | Move to next |

| 15 | start | myth | - | Move to start | Move to next |

As demonstrated, the system successfully identifies the two matching phrases, “same family” and “separate existence.”

Real-world Example

In a recent project, a client presented me with the following challenge: they possessed a substantial collection of articles and PhD theses related to their field of expertise and had compiled a personalized list of phrases representing specific titles and rules within that field.

The client’s objective was to establish links between the articles/theses and these phrases, enabling them to select a random set of phrases and instantly retrieve a list of articles/theses mentioning those phrases.

As previously discussed, this problem comprises two parts: indexing the phrases into a trie and performing the actual search. The following sections outline a simple implementation in C#. Note that file handling, encoding issues, text cleanup, and similar concerns are omitted for brevity as they fall outside the scope of this article.

Indexing

The indexing process involves iterating through each phrase and inserting it into the trie, with each node/level representing a single word. Nodes are represented using the following class:

| |

Each phrase is assigned an ID, which can be a simple incremental number, and passed to the following indexing function (where the variable root represents the trie’s root):

| |

Searching

The search process directly implements the trie algorithm described earlier:

| |

Performance

The code presented here is extracted and simplified from the actual project. Executing this code on the same machine [1] using the same test dataset [2] resulted in a runtime of 2.5 seconds for trie construction and 0.3 seconds for the search—a significant improvement.

Variations

It’s crucial to acknowledge that the algorithm described in this tutorial may encounter limitations in certain edge cases. It is primarily designed with predefined search terms in mind.

For instance, if the beginning of one search term is identical to a portion of another search term, such as:

- "to share and enjoy with friends"

- “I have two tickets to share with someone”

and the text body contains a phrase that leads the trie pointer down the wrong path, like:

I have two tickets to share and enjoy with friends.

the algorithm will fail to match any term because the trie indicator won’t return to the start node until the text indicator has already moved past the beginning of the matching term in the text body.

Before implementing this algorithm, carefully consider whether your application might encounter such edge cases. If so, you can modify the algorithm to utilize additional trie indicators to simultaneously track all potential matches instead of just one at a time.

Conclusion

Text search is a complex field in computer science, teeming with both challenges and solutions. While the data scale I encountered (23MB of text, equivalent to numerous books) might seem like a specialized problem, developers working with linguistics research, archiving, or other data-intensive domains regularly handle far larger datasets.

As demonstrated in this trie data structure tutorial, selecting the appropriate algorithm for the task is paramount. In this instance, the trie approach resulted in an impressive 99.93% reduction in runtime, from over an hour to under 3 seconds.

While this is by no means the only effective approach, it is a simple and functional solution. I hope you found this algorithm insightful and wish you the best in your coding endeavors.

[1] The machine used for testing had the following specifications:

- Intel i7 4700HQ processor

- 16GB of RAM

Testing was conducted on both Windows 8.1 using .NET 4.5.1 and Kubuntu 14.04 using the latest versions of Mono, with comparable results.

[2] The test dataset comprised 280,000 search phrases totaling 23.5MB in size and a text body of 1.5MB.