In my daily development work, I heavily rely on Entity Framework. While it offers great convenience, it sometimes suffers from performance issues. Although there’s plenty of excellent advice available on enhancing EF performance, such as simplifying queries, using parameters effectively, and selecting only necessary fields, certain scenarios pose challenges. One such case is performing complex Contains operations on multiple fields, essentially involving joins with in-memory lists.

Problem

Let’s examine this issue with an example:

| |

This code doesn’t function in EF 6, and although it works in EF Core, the join operation is executed locally. With a database containing ten million records, this results in the entire dataset being loaded into memory, leading to significant consumption. While this behavior is expected and not a bug in EF, a solution for such scenarios would be highly beneficial. This article explores alternative approaches to address this performance bottleneck.

Solution

We’ll experiment with various methods, progressing from basic to more advanced techniques. Each step will include code snippets, performance metrics like execution time and memory usage, and a maximum runtime limit of ten minutes for benchmarking purposes.

The benchmarking program, available at repository, is implemented using C#, .NET Core, EF Core, and PostgreSQL. The testing environment consists of a machine equipped with an Intel Core i5 processor, 8 GB RAM, and an SSD.

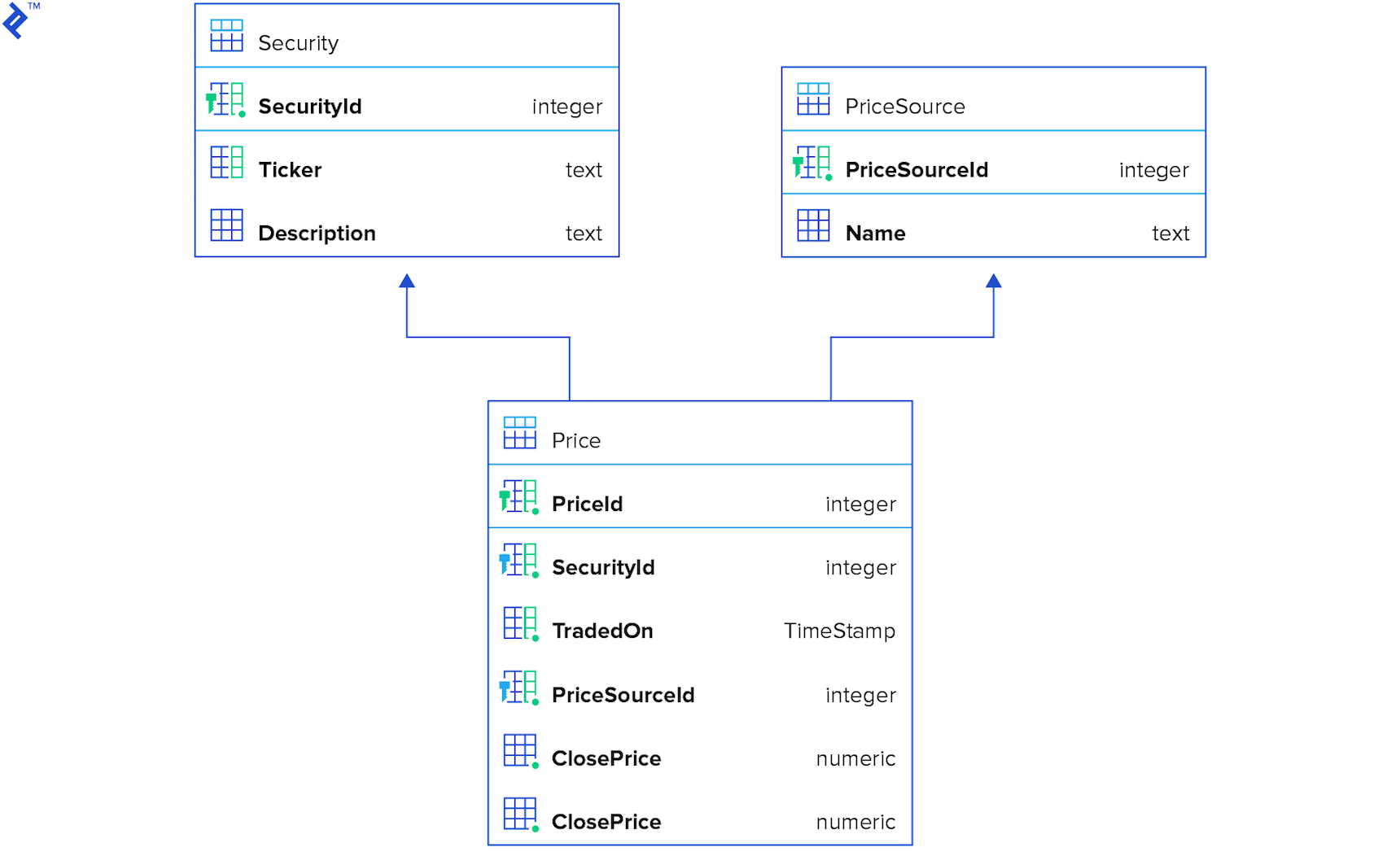

The database schema used for testing is as follows:

Option 1: Simple and Naive

We’ll begin with a straightforward approach as a starting point.

| |

This algorithm is quite basic: for each element in the test data, it locates a corresponding element in the database and adds it to the result set. While easy to implement, read, and maintain, its simplicity comes at the cost of performance. Even with indexes on all three columns, network communication overhead creates a bottleneck.

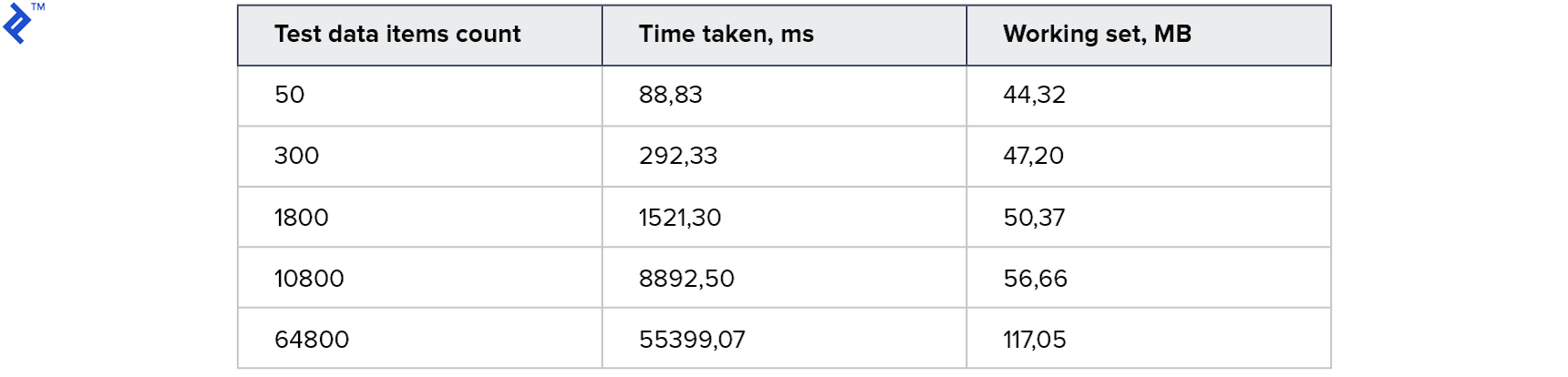

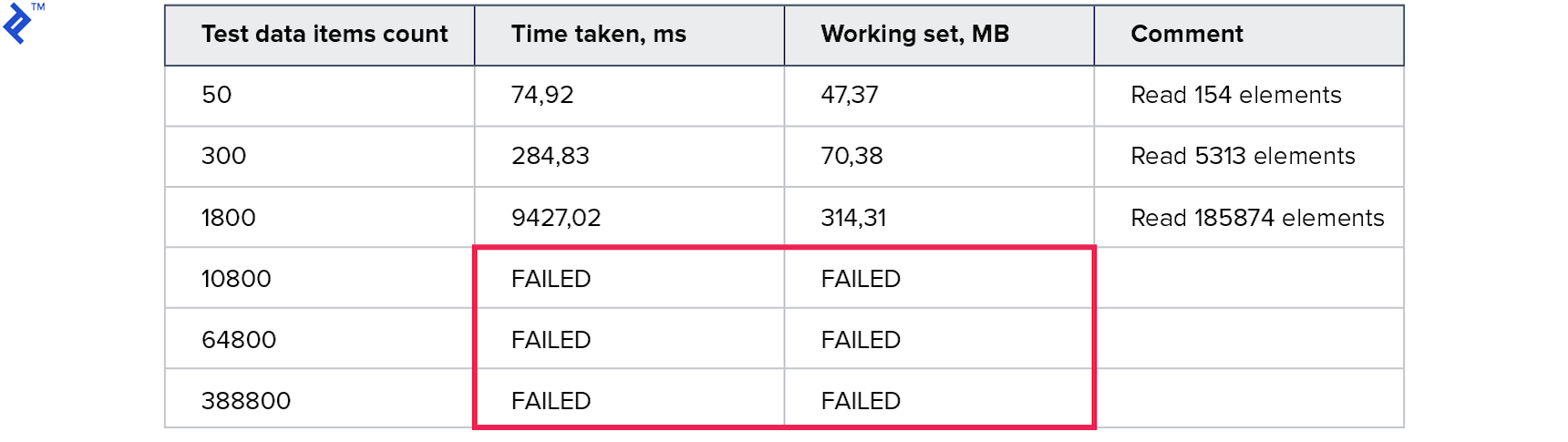

The performance metrics are as follows:

For larger datasets, the execution time reaches approximately one minute. Memory consumption remains reasonable.

Option 2: Naive with Parallelism

Let’s introduce parallelism into the mix. The underlying idea is to leverage multiple threads to query the database concurrently, potentially improving performance.

| |

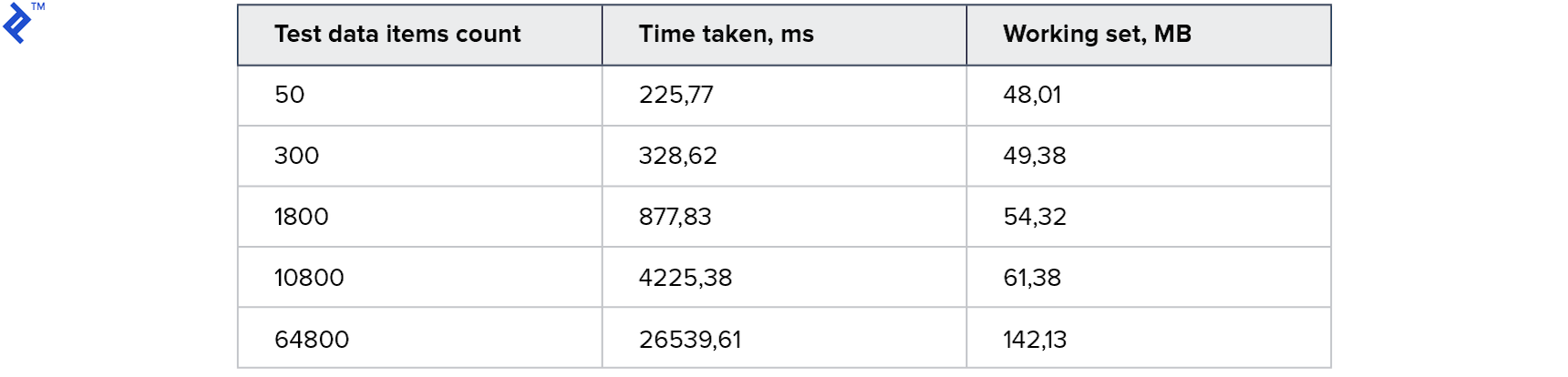

Interestingly, this approach performs slower than the first solution for smaller datasets. However, it outperforms the initial approach for larger datasets, demonstrating a two-fold improvement in this particular instance. Memory consumption shows a slight increase but remains relatively unchanged.

Option 3: Multiple Contains

Let’s explore another strategy:

- Create three separate collections containing unique values for Ticker, PriceSourceId, and Date.

- Execute a single query filtered by three

Containsoperations. - Perform a local recheck (explained below).

| |

This approach poses some issues due to its data-dependent nature. While it can be highly performant if only the required records are retrieved, there’s a risk of fetching significantly more data, potentially up to 100 times the necessary amount.

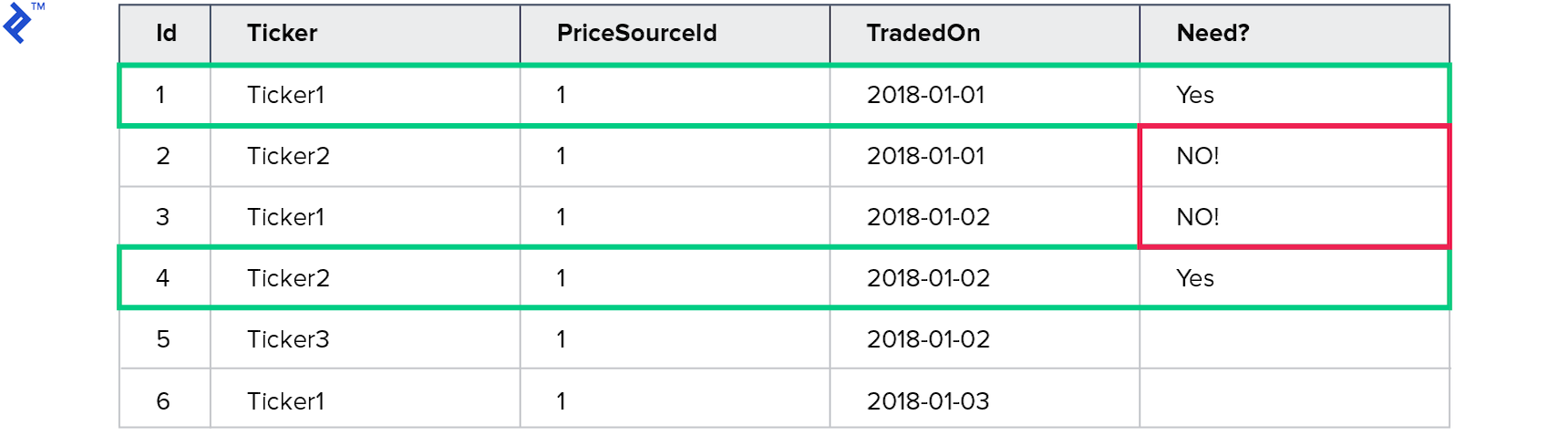

Consider the following test data:

This query aims to retrieve prices for Ticker1 traded on 2018-01-01 and Ticker2 traded on 2018-01-02. However, the query returns four records.

The unique values for Ticker are Ticker1 and Ticker2, while for TradedOn, they are 2018-01-01 and 2018-01-02. As a result, four records satisfy the query criteria.

This highlights the need for a local recheck and the potential pitfalls of this approach.

Here are the metrics:

The memory consumption is exceptionally high, and tests with larger datasets timed out after ten minutes.

Option 4: Predicate Builder

Let’s shift gears and explore building an Expression for each test dataset.

| |

The resulting code becomes quite complex, as building expressions often involves reflection, which can be slow. However, this approach enables us to construct a single query using a series of ... (.. AND .. AND ..) OR (.. AND .. AND ..) OR (.. AND .. AND ..) ... conditions.

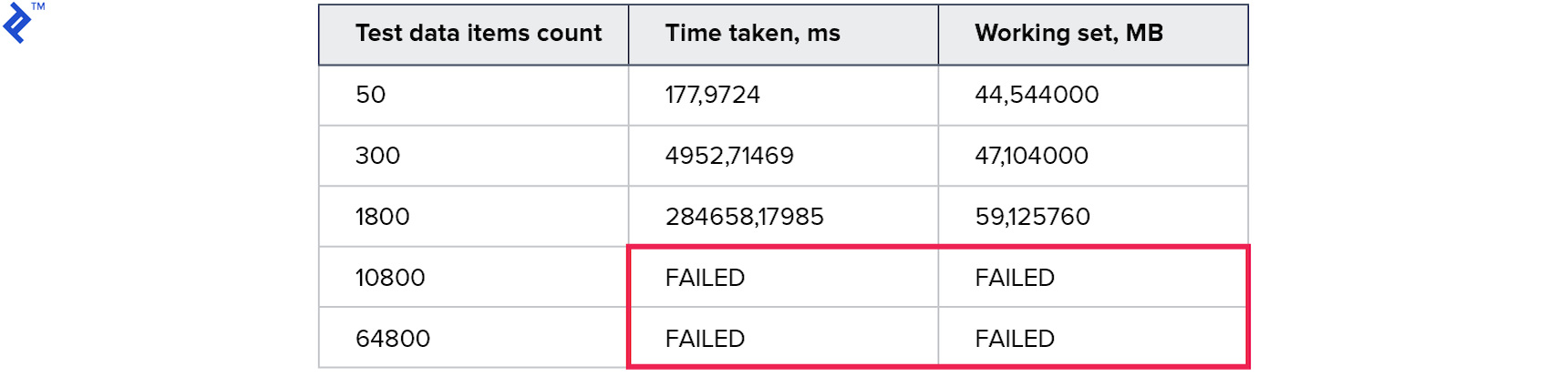

Let’s analyze the results:

Unfortunately, this approach performs even worse than the previous ones.

Option 5: Shared Query Data Table

Our next approach involves introducing an additional table in the database to store query data temporarily. This table facilitates the following steps for each query:

- Initiate a transaction (if not already started).

- Populate the temporary table with query data.

- Execute the query.

- Roll back the transaction to remove the temporary data.

| |

Let’s examine the metrics:

This approach yields impressive results with fast execution times and reasonable memory consumption. However, it comes with several drawbacks:

- An extra table is required solely for this specific query type.

- Transactions, which consume database resources, are necessary.

- Data is written to the database during a read operation, potentially causing issues with read replicas.

Despite these drawbacks, this approach proves to be efficient, readable, and benefits from query plan caching.

Option 6: MemoryJoin Extension

This approach utilizes a NuGet package called EntityFrameworkCore.MemoryJoin, which, despite its name, supports both EF 6 and EF Core. MemoryJoin sends the query data as VALUES to the server, enabling the SQL server to handle the entire operation.

Let’s take a look at the code:

| |

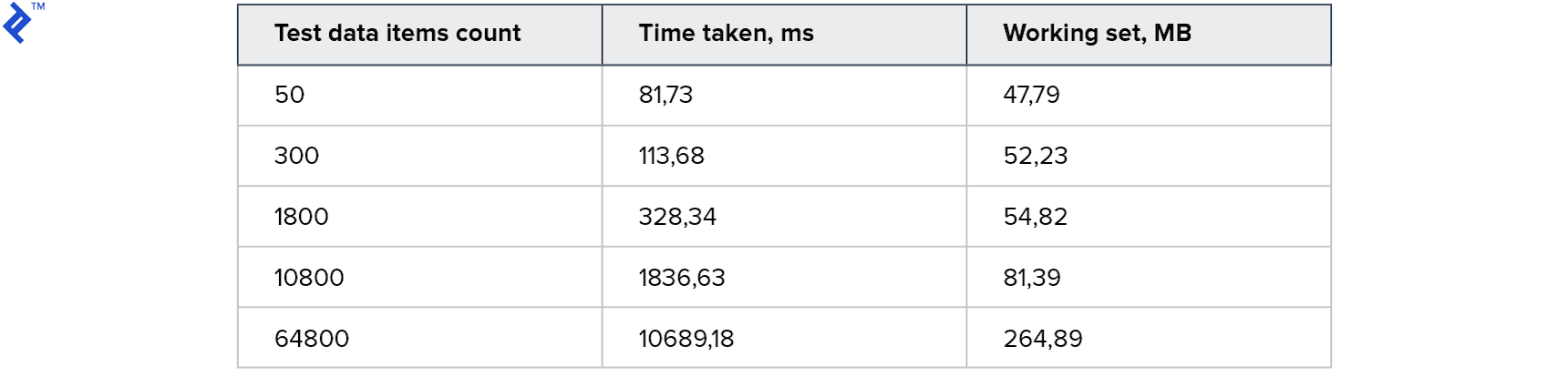

And here are the metrics:

The results are remarkable, achieving three times the speed of the previous approach and clocking in at 3.5 seconds for 64K records. The code remains simple and understandable, and it functions seamlessly with read-only replicas.

Let’s analyze the generated query for three elements:

| |

In this case, the actual values are efficiently transferred from memory to the SQL server using the VALUES construction. This allows the SQL server to leverage indexes effectively and perform a fast join operation.

However, there are a few limitations (more details available on my blog):

- An extra DbSet needs to be added to the model (although it doesn’t have to be created in the database).

- The extension has limitations regarding the number of properties supported in model classes, supporting up to three properties of each data type: string, date, GUID, float/double, and int/byte/long/decimal. While this limitation might be irrelevant in most cases, custom classes can be used as a workaround.

Conclusion

Based on the tested approaches, MemoryJoin emerges as the clear winner. While some might argue against its use due to its limitations, the performance gains it offers are significant and often outweigh the drawbacks. Similar to any powerful tool, it requires careful consideration and understanding of its inner workings, especially in the hands of experienced developers. This extension has the potential to significantly boost performance, and perhaps one day, Microsoft might incorporate dynamic VALUES support directly into EF Core.

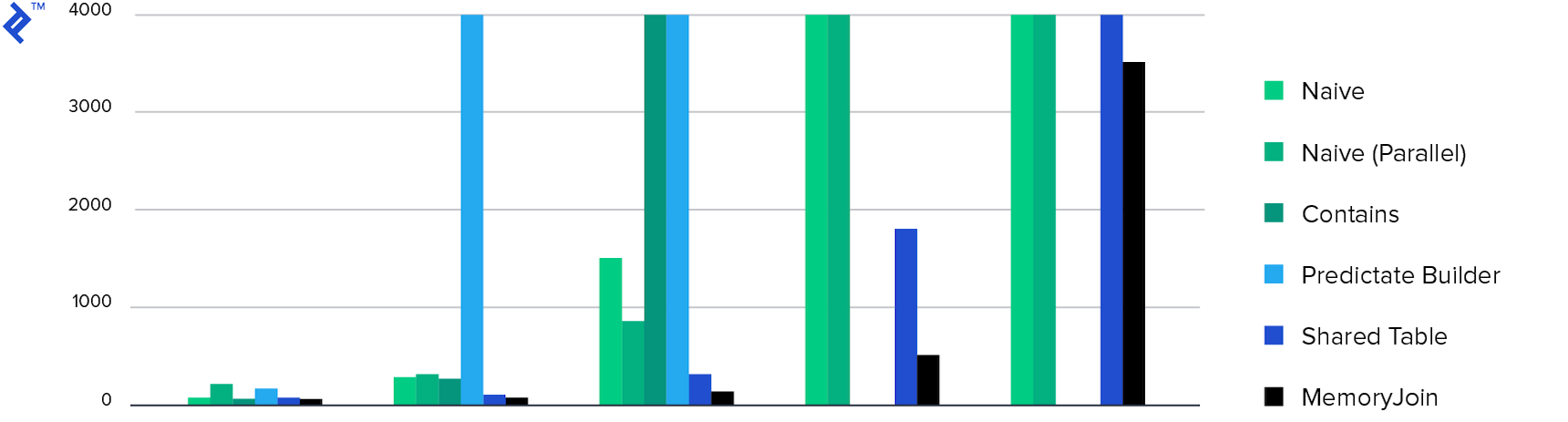

Finally, here are some diagrams to summarize the results:

The first diagram showcases the execution time for each approach. MemoryJoin clearly stands out as the only option that completes the task within a reasonable timeframe. Only four approaches, including MemoryJoin, can handle larger datasets effectively.

The next diagram illustrates memory consumption, showing comparable results for all approaches except for the “Multiple Contains” method, which exhibits exceptionally high memory usage as previously discussed.