When team leads ask developers to write excessive boilerplate code instead of utilizing efficient methods, persuasive arguments are needed. Software engineers, by nature, seek to automate tasks and minimize redundancy.

While acknowledging that NgRx does involve some boilerplate, it’s crucial to recognize the powerful development tools it offers. This article aims to demonstrate that dedicating extra effort to code writing can yield significant, worthwhile benefits.

The introduction of Dan Abramov’s Redux library led many developers to embrace state management, sometimes driven by trend rather than necessity. However, applying state management to basic “Hello World” projects often resulted in repetitive code, adding complexity without real value.

This frustration led some developers to abandon state management altogether.

Initial Concerns with NgRx

The initial skepticism towards NgRx stemmed from this boilerplate concern. The bigger picture was initially unclear. NgRx, a library rather than a paradigm or mindset, necessitates a broader understanding, particularly of functional programming, to appreciate its full potential. This shift in perspective often leads to writing boilerplate code with a sense of satisfaction—a sentiment I share, having transitioned from an NgRx skeptic to an admirer.

My early experience with state management mirrored this journey, leading me to abandon the library due to excessive boilerplate. Driven by my passion for JavaScript, I explore all popular frameworks, which led me to React and its concept of Hooks.

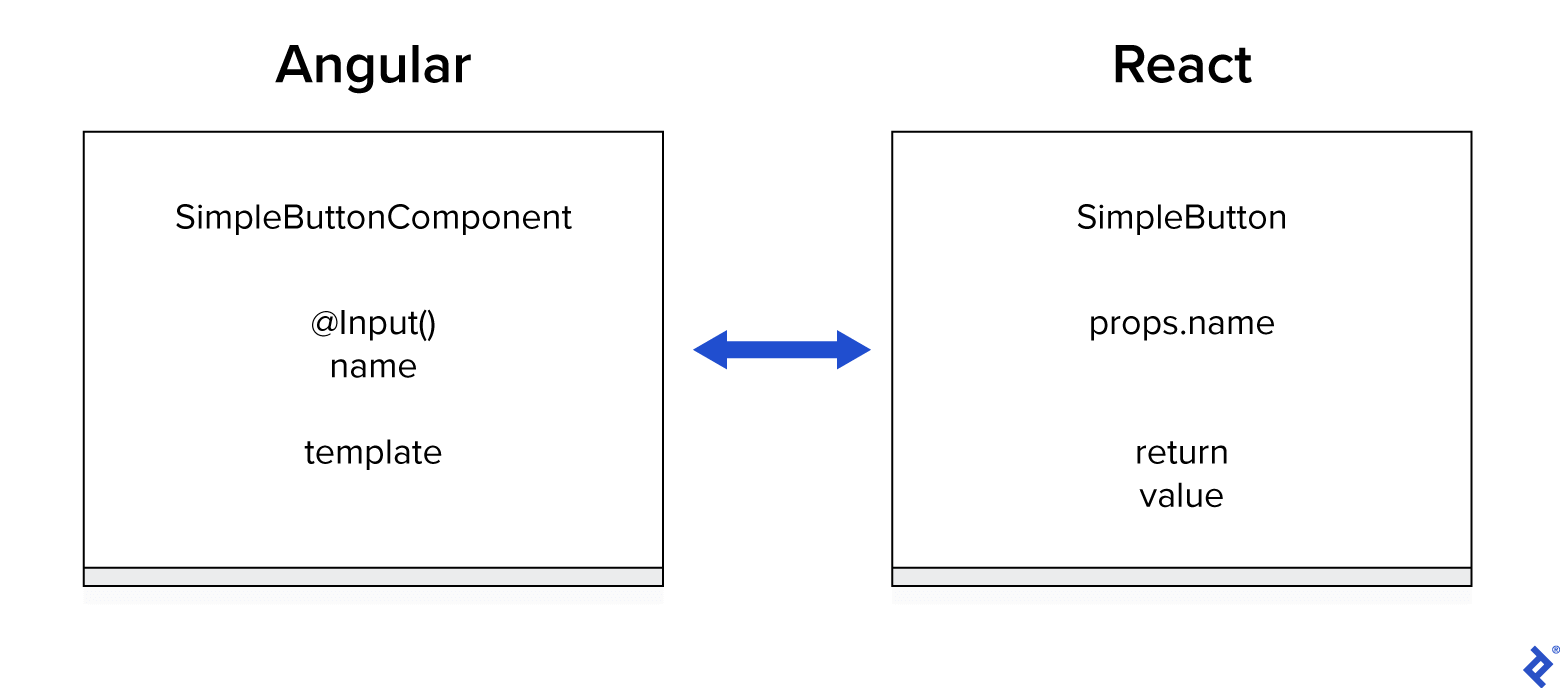

Similar to Angular Components, Hooks are functions accepting arguments and returning values, with the capacity to hold state through side effects. For instance, a basic Angular button translates to React as follows:

| |

The transformation is straightforward:

- SimpleButtonComponent becomes SimpleButton

@Input() namebecomesprops.name- Template becomes return value

The React SimpleButton function exhibits a crucial characteristic in functional programming: it’s a pure function. This term, familiar to most developers, is highlighted twice in NgRx.io Key Concepts:

- State changes are handled by pure functions called

reducers, which calculate a new state based on the current state and the latest action. - Selectors are pure functions used for selecting, deriving, and composing state fragments.

React encourages the use of Hooks as pure functions, mirroring Angular’s Smart-Dumb Component paradigm.

This realization highlighted a gap in my functional programming skills. Grasping NgRx became effortless once I understood the core concepts of functional programming. This “Aha!” moment solidified my understanding and fueled my desire to utilize NgRx effectively.

This article chronicles my learning journey and newfound appreciation for NgRx, moving beyond its trendiness to highlight its genuine benefits.

Let’s delve into functional programming.

Functional Programming

Functional programming is a paradigm presents a unique programming approach, rich in definitions and principles. However, mastering NgRx (and JavaScript in general) requires understanding its core concepts:

- Pure Function

- Immutable State

- Side Effect

Remember, it’s a paradigm, not a library like functional.js. It’s a way of thinking about software development. Let’s start with the cornerstone: pure function.

Pure Function

A pure function adheres to two fundamental rules:

- Consistent output for the same input

- Absence of observable side effects during execution (e.g., external state changes, I/O operations)

Essentially, a pure function transparently accepts arguments (or none) and returns a predictable value, guaranteeing no side effects like network calls or global state modifications.

Consider these examples:

| |

- The first function is pure, always returning the same output for the same input.

- The second function, being non-deterministic, is impure as its output varies for the same input.

- The third function is impure due to the

console.logside effect.

Identifying pure functions is straightforward. Why are they preferable? Their simplicity makes them easier to reason about. When encountering a pure function call in code, understanding its behavior requires minimal effort. This clarity is invaluable for debugging complex applications, saving significant time.

Testing is equally simplified. No need for injections or mocks; just provide arguments and verify the output. This strong connection between tests and logic promotes code understandability.

Memoization, a performance-enhancing technique, is inherently supported by pure functions. Since identical input guarantees identical output, results can be cached, avoiding redundant computations. NgRx leverages this extensively for its speed.

The question of side effects arises. As humorously noted by Russ Olsen in his GOTO talk, clients don’t pay for pure functions but for the side effects they produce. Indeed, a Calculator pure function is useless without displaying its results. Side effects have their place in functional programming, which we’ll explore shortly.

For now, let’s move on to another crucial concept for managing complex architectures: immutable state.

Immutable State

The concept of an immutable state is simple:

- States can only be created or deleted, not updated.

In essence, updating a User object’s age:

| |

…would be written as:

| |

Each change results in a new object copying properties from the previous one, adhering to immutability.

Strings, Booleans, and Numbers are inherently immutable, preventing modifications to existing values. In contrast, Dates are mutable, allowing manipulation of the same object.

Immutability extends across the entire application. A function modifying a user’s age shouldn’t alter the original object but create a new one with the updated age:

| |

Why prioritize this? The benefits are compelling.

In back-end programming, immutability facilitates parallel processing. Since state changes are reference-independent and updates create new objects, tasks can be divided and processed concurrently across multiple threads or servers without shared memory concerns.

For frameworks like Angular and React, parallel processing significantly enhances performance. For instance, Angular’s default change detection mechanism checks every property of objects passed through Input bindings to determine re-rendering needs. However, using ChangeDetectionStrategy.OnPush instead triggers checks by reference, significantly boosting performance in large applications. Immutable state updates inherently provide this optimization.

Similar to pure functions, immutable states simplify reasoning and testing. Knowing each change results in a new state enables precise tracking of modifications, facilitating debugging and implementing undo/redo functionalities like React DevTools.

Conversely, mutable states lack this change history, making debugging a challenge. Immutable states, akin to bank account transaction logs, provide valuable insights into application behavior.

With immutability and purity covered, let’s address the final core concept: side effect.

Side Effect

A side effect can be broadly defined as:

- In computer science, any operation, function, or expression that modifies state variables outside its local environment is said to have a side effect. It produces an observable effect beyond returning a value (the main effect) to the invoker.

Essentially, any action altering state outside the function scope—including I/O operations and tasks not directly related to the function—is considered a side effect. However, they contradict functional programming principles and should be avoided within pure functions, as they compromise purity.

Nevertheless, applications rely on side effects for functionality. In Angular, avoiding side effects extends beyond pure functions to Components and Directives.

Let’s explore how to implement these principles within Angular.

Functional Angular Programming

Angular development emphasizes decoupling components into smaller, manageable units to enhance maintainability and testability. This separation is crucial for dividing business logic. Moreover, Angular encourages developers to relegate components solely to rendering, shifting all business logic into services.

To further refine this approach, Angular developers introduced the “Dumb-Smart Component” pattern, advocating against service calls within small components. While business logic resides in services, invoking these services, awaiting responses, and subsequently updating state introduce behavioral logic into components.

The solution lies in creating a single Smart Component (Root Component) housing business and behavioral logic, passing states through Input Properties, and triggering actions by listening to Output parameters. This relegates small components purely to rendering. While the Root Component handles service calls, its scope remains limited to business logic, not rendering.

Consider a Counter Component example. This component consists of two buttons for increasing or decreasing a value and a displayField showing the currentValue. This results in four components:

- CounterContainer

- IncreaseButton

- DecreaseButton

- CurrentValue

The CounterContainer houses all logic, reducing the other three to pure renderers:

| |

Their simplicity and purity are evident. Without state or side effects, they rely solely on input properties and event emission, making them incredibly easy to test. True to their name, these pure components depend solely on input parameters, have no side effects, and consistently return the same value (template string) for identical input.

Thus, pure functions in functional programming translate to pure components in Angular. Where does the logic reside then? It’s within the CounterComponent:

| |

While the CounterContainer handles behavioral logic, it lacks rendering aspects (declaring components within the template) as those are delegated to pure components.

Injecting any number of services is permissible here as data manipulation and state changes are managed within this scope. It’s worth noting that deeply nested component structures might require multiple smart components instead of a single root-level one, adopting the same pattern. The decision depends on the complexity and nesting level of each component.

This pattern smoothly transitions into the NgRx library, acting as a layer above it.

NgRx Library

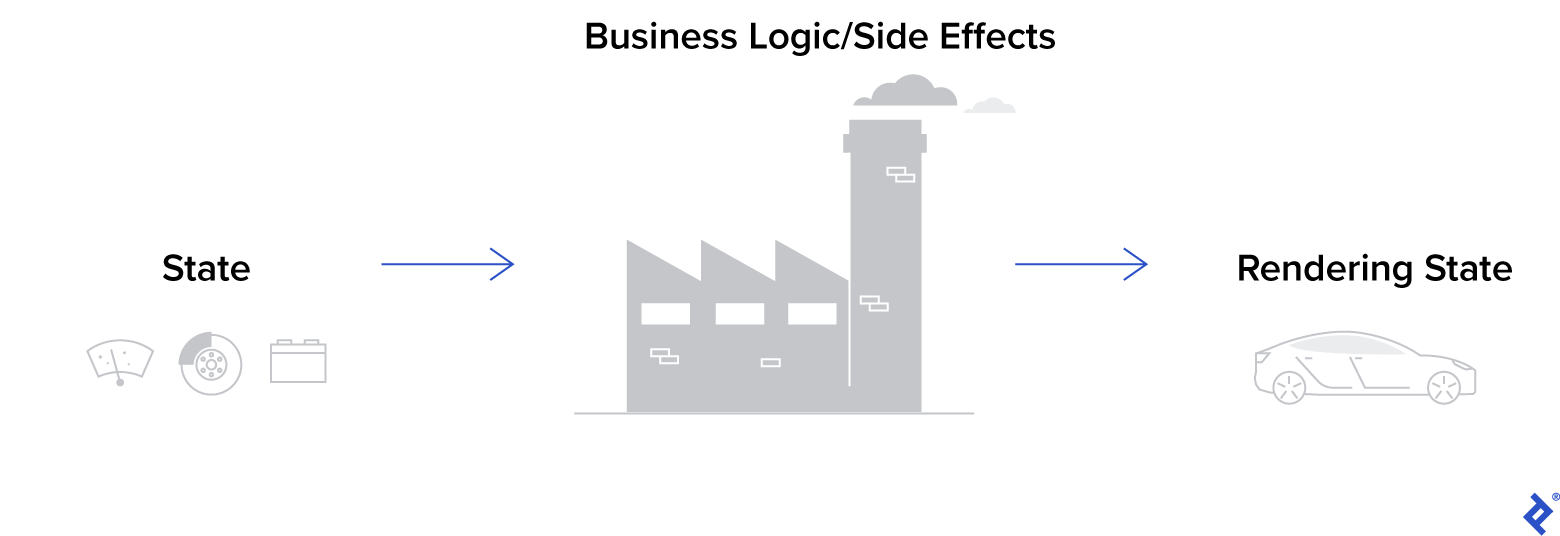

Web applications can be broadly categorized into three core parts:

- Business Logic

- Application State

- Rendering Logic

Business Logic encompasses all application behavior, including networking, input/output operations, API interactions, and more.

Application State represents the application’s state at a given moment, encompassing both global aspects like the currently logged-in user and local aspects like the current value of a Counter Component.

Rendering Logic deals with rendering aspects, such as displaying data using the DOM, creating/removing elements, and so on.

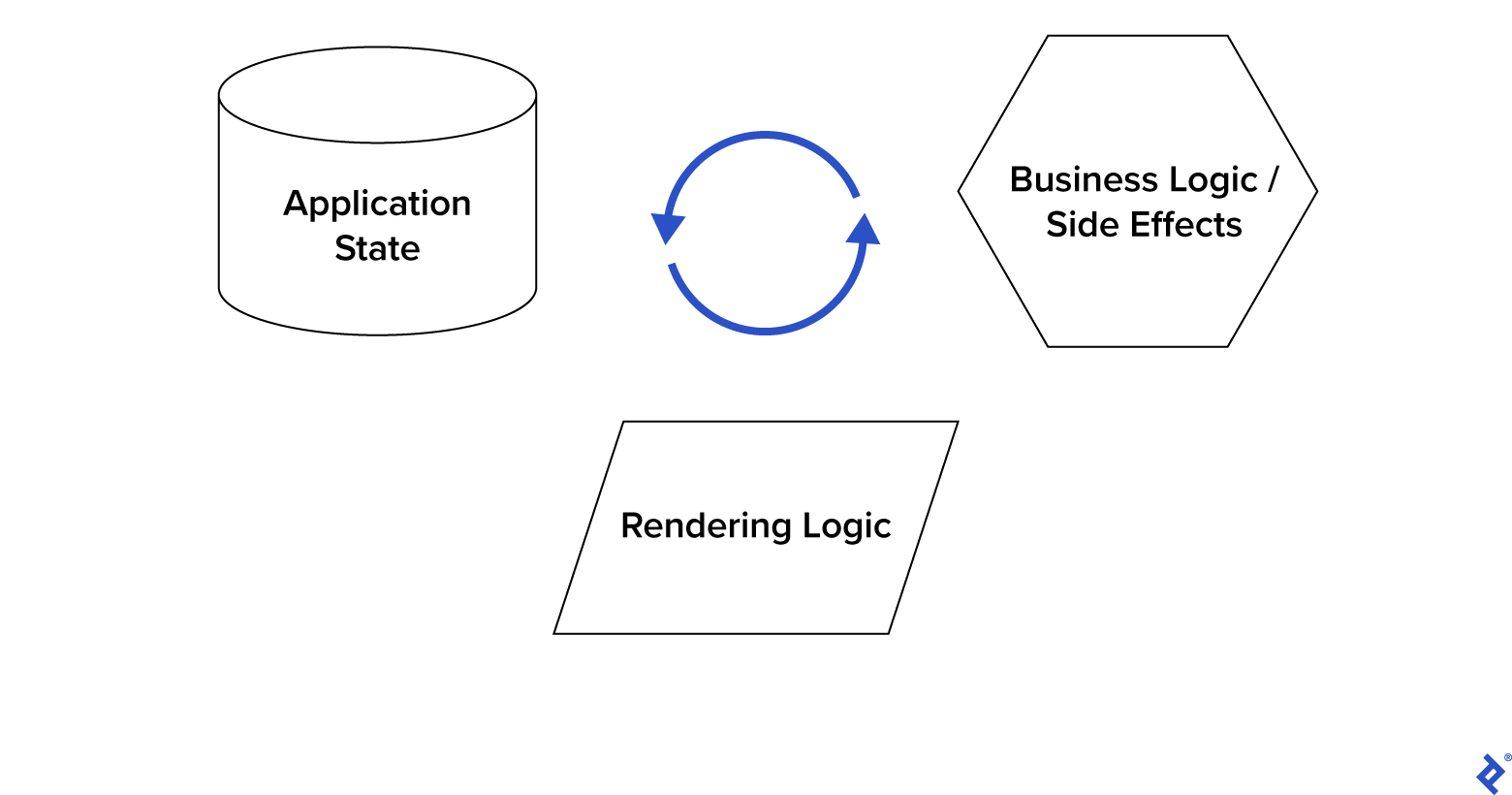

While the Dumb-Smart pattern decouples Rendering Logic from Business Logic and Application State, further separation is beneficial due to their conceptual differences. Application State is a snapshot of the app at a specific time, while Business Logic represents static functionality. This separation is crucial because Business Logic often involves side effects that should be minimized within the application code. This is where NgRx, with its functional paradigm, excels.

NgRx facilitates this decoupling through its three main components:

- Reducers

- Actions

- Selectors

When combined with functional programming principles, they provide a robust framework for managing applications of any scale. Let’s explore each component.

Reducers

A reducer is a pure function with a simple signature: it takes the old state as input and returns a new state, either derived from the old one or entirely new. The state itself is a single object persisting throughout the application’s lifecycle, similar to an HTML root element.

Modifying the state object directly is prohibited; instead, reducers are used. This approach offers several advantages:

- State change logic is centralized, making it easy to track modifications.

- Reducers, being pure functions, are easy to test and manage.

- Memoization is applicable to reducers due to their purity, allowing caching and reducing computational overhead.

- State changes are immutable, always returning a new state object instead of modifying the existing one. This enables “time travel” debugging.

Here’s a basic reducer example:

| |

Despite its simplicity, it illustrates the fundamental structure of all reducers, regardless of their complexity. They all share the same benefits. An application can have numerous reducers, each serving a specific purpose.

For our Counter Component, the state and reducers would look like this:

| |

With the state removed from the component, we need a mechanism to update it and invoke the appropriate reducer. This is where actions come in.

Actions

Actions serve as notifications for NgRx to execute a reducer and update the state, forming a crucial aspect of the library. They are simple objects associated with specific reducers. Dispatching an action triggers the corresponding reducer. In our example, we could have the following actions:

| |

With actions linked to reducers, we can refine our Container Component to dispatch actions as needed:

| |

Note: The state has been temporarily removed and will be added back shortly.

Now, the CounterContainer is free from state change logic, knowing only which actions to dispatch. The next step is displaying this data in the view, which is where selectors come in.

Selectors

Selectors are pure functions that, unlike reducers, don’t modify the state. They solely retrieve specific parts of it. In our example, we could have three simple selectors:

| |

These selectors enable retrieving individual slices of the state within our smart CounterContainer component:

| |

These selections are inherently asynchronous, like Observables, but this detail is inconsequential from a pattern perspective. Synchronous selections would function similarly, simply retrieving data from the state.

Stepping back, we’ve successfully decoupled our Counter Application into three main parts: the business logic, the application state, and the rendering logic. They remain oblivious to each other’s inner workings, communicating solely through actions and selectors.

This decoupling is so complete that the entire State Application code could be reused in another project, such as a mobile version, requiring only the rendering layer to be re-implemented.

What about testing? This is where NgRx truly shines. Testing this example project becomes incredibly straightforward due to the use of pure functions and pure components. Scaling the project to hundreds of components while adhering to this pattern would still result in maintainable and testable code, avoiding a tangled mess.

We’re almost there. The final piece of the puzzle is handling side effects.

Side Effects

Despite numerous mentions, we haven’t addressed where side effects should reside. They are the finishing touch, easily extracted from the application code thanks to the established pattern.

Let’s introduce a timer to our Counter Application, incrementing the value every three seconds. This simple side effect, similar to an Ajax request, needs a place to live.

Most side effects serve one of two purposes:

- Performing actions outside the state environment

- Updating the application state

Storing state in LocalStorage exemplifies the first purpose, while updating state based on an Ajax response illustrates the second. However, they share a common requirement: a trigger. Each side effect needs an initial invocation to initiate its action.

As previously mentioned, NgRx provides a mechanism for this: actions. Dispatching an action can trigger any side effect. Here’s a pseudo-code representation:

| |

Straightforward, isn’t it? As mentioned earlier, side effects either update something or not. If no updates are involved, no further action is needed. But what about updating the state? The process mirrors a component’s approach: dispatching another action. Thus, we trigger an action within the side effect, which in turn updates the state:

| |

With this, we have a fully functional application.

Summarizing Our NgRx Experience

Before concluding our NgRx exploration, it’s crucial to highlight a few points:

- The code snippets used are simplified pseudo-code for demonstration purposes. The actual source code can be found in NgRx.

- There are no official guidelines confirming my interpretation of connecting functional programming with NgRx. This understanding stems from my own research and exploration of numerous articles and code samples created by experts in the field.

- Real-world NgRx implementations are inherently more complex than this simplified example. The goal was not to downplay its complexity but to emphasize that the effort invested in adopting this approach yields significant long-term benefits.

- Overusing NgRx, regardless of application size or complexity, can be detrimental. Certain scenarios, like forms heavily tied to the DOM, are ill-suited for NgRx. Attempting to decouple them would likely lead to frustration.

- Excessive boilerplate code, even in small examples, can be overwhelming despite its potential benefits. In such cases, integrating with other libraries within the NgRx ecosystem, like ComponentStore, is a viable solution.