A quantum computer with sufficient power has the potential to decrypt modern encryption methods, potentially exposing all digital communications worldwide to cyberattacks. Although the shift from the current noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) computers, which are susceptible to errors and have size limitations, to those capable of compromising existing cryptographic protocols is predicted to span years or even decades, the recent surge in research, experimentation, and investment in quantum technologies suggests this possibility might be closer than initially thought.

Quantum computing has the capacity to revolutionize not only cryptography and cybersecurity but also other critical areas such as software optimization, chip design, and complex system modeling, among many more.

Currently, engineers can access tools like quantum circuit libraries, quantum simulators, and even physical quantum computers through cloud platforms. However, adopting quantum computing requires a significant shift from conventional computing models. In this article, Toptal quantum engineers clarify the present state of quantum computing, highlighting its importance, how it differs from traditional computing, and the opportunities it unlocks. Moreover, they delve into practical tools like Cirq and TensorFlow Quantum, which provide hands-on experience with quantum computing.

The Significance of Quantum Computing: Why It Matters

Imagine a vast library housing thousands of books. You are aware that the library holds the answer to a specific problem, but you’re unsure which book or combination of books contains it. Each book represents a possible solution.

To find the answer, you could have a single scholar meticulously examine the books one by one, sentence by sentence, until they chance upon it. However, this process would be incredibly time-consuming unless they are exceptionally lucky. The larger the library, the more challenging the search.

Now, envision a scholar with the extraordinary ability to inspect all books simultaneously. They wouldn’t need to proceed sequentially but could instantly perceive a comprehensive view of the entire library and its contents. Naturally, they would discover the solution much faster than the scholar without this ability.

Traditional computing functions similarly to the first scholar. It excels at tasks that can be executed in a straightforward, sequential manner but struggles as problems become more intricate and demand the exploration of numerous possibilities concurrently.

Quantum computing, in contrast, offers a range of algorithms that enable faster data processing compared to classical computers. In our analogy, one example is Grover’s search algorithm, which can locate a specific item within a large dataset significantly faster than classical computing. It accomplishes this by leveraging quantum properties like superposition and interference, which we’ll explore in more detail later in this article.

This capability results in a quadratic speedup over classical search algorithms for unstructured data, which essentially represents the theoretical speed limit for quantum algorithms addressing this type of problem. For structured searches where additional information about the dataset is available, other quantum algorithms can outperform Grover’s algorithm. One instance is Shor’s algorithm, which can factor large numbers and solve discrete logarithm problems exponentially faster than classical algorithms.

Quantum Solutions for Quantum Challenges

Quantum computing is poised to transform numerous fields, and cryptography and cybersecurity are among those most likely to be revolutionized by this technology. Algorithms like RSA encryption, the bedrock of much of today’s digital security, rely on the fact that factoring a sufficiently large number to break one of its instances using classical computers could take centuries. However, this type of task is precisely where Shor’s algorithm excels. Running on a sufficiently stable quantum computer, this algorithm theoretically possesses the ability to crack these encryption methods within mere hours or days.

The potential impact is so significant that the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has been diligently developing algorithms resistant to these attacks for years, integrating them into a post-quantum cryptographic standard to safeguard information assets even after the development of large-scale quantum computers. The World Economic Forum estimates that over 20 billion digital devices will need replacement or updates in the coming 10 to 20 years to accommodate new forms of quantum-resistant encrypted communication.

New communication techniques and protocols are also being developed to further secure systems. For instance, Quantum key distribution (QKD) relies on the principles of quantum mechanics to enable two parties to establish a shared secret key, facilitating secure communication. Meanwhile, ongoing research in quantum secure direct communication protocols aims to enable the direct and secure transmission of information.

Cybersecurity isn’t the only field poised to reap the benefits of quantum-centric approaches. Quantum computing also holds immense promise in healthcare. Joao Diogo de Oliveira explains that its capacity to simulate molecular interactions with unprecedented detail can accelerate drug discovery. “By harnessing quantum algorithms, we can explore vast chemical spaces more efficiently and predict molecular behaviors with greater accuracy. Quantum computers can perform complex simulations that allow for more precise identification of potential drug candidates. This capability reduces the time and costs associated with the early stages of drug development. Furthermore, quantum-enhanced ML models can analyze massive datasets to identify patterns missed by classical methods, thereby improving drug efficacy and safety predictions. This integration has the potential to bring revolutionary treatments to market faster than ever,” he notes.

Quantum algorithms like Grover’s algorithm and quantum annealing are also likely to have a profound impact on optimization problems, assisting in finding more efficient solutions for large-scale, complex challenges in logistics, finance, and scheduling. However, the influence of quantum computing isn’t limited to practical applications; it extends to entire industries and scientific disciplines. Fields such as materials science, renewable energy research, climate modeling, and particle physics could all benefit from advancements in quantum computing power.

Quantum Computing: A Historical Perspective and Current State

Initially confined to the realm of theoretical physics, the concept of quantum computing began to materialize in the early 1980s. This evolution was driven by pioneers such as Nobel laureate Richard Feynman and Paul Dirac Prize recipient David Deutsch, who envisioned machines capable of harnessing quantum mechanics to achieve unprecedented processing capabilities. By 1996, a team under the leadership of IBM physics researcher Isaac Chuang successfully developed the world’s first quantum computer, which could handle a mere two quantum bits, or “qubits”—the quantum equivalent of the traditional bit and the fundamental unit of quantum computing.

Chuang’s device manipulated individual atoms of hydrogen and chlorine within chloroform, making them function as a computer. Although the system remained stable for only a few nanoseconds and was limited to solving simple problems, this achievement provided concrete evidence that quantum technology was more than just a theoretical concept.

By the late 2010s, quantum processors capable of operating on 50 to 72 qubits had emerged. In 2023, IBM unveiled IBM Quantum Condor, a quantum processor boasting over 1,000 qubits, along with a smaller processor known as the IBM Quantum Heron. Both processors can execute or simulate parallel processes, with the more compact Heron exhibiting significantly fewer errors and faster overall performance compared to Condor. These advancements have brought the practical applications of quantum computing considerably closer to reality.

While these represent substantial strides in the field, it’s crucial to acknowledge that current quantum computers lack the power and stability to genuinely rival classical computers in solving complex problems and processing the massive amounts of data that would set them apart from traditional machines. Today’s quantum computers primarily serve research purposes. The quantum computing revolution remains on the horizon, but quantum operations can be simulated on classical computers, and developers can gain practical experience with quantum computing using various tools available in the market.

Delving into the Fundamentals of Quantum Mechanics: Superposition, Entanglement, and Interference

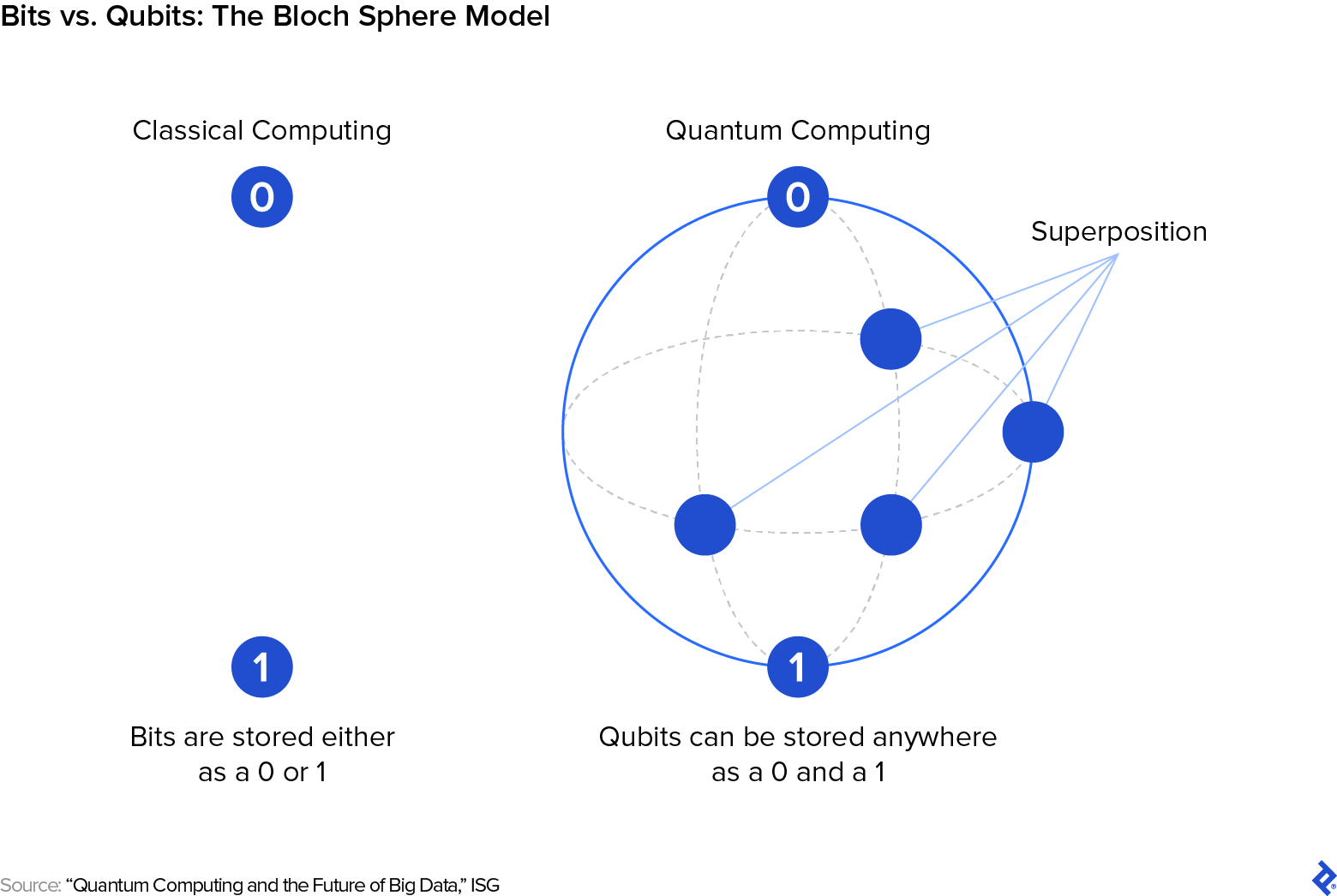

Quantum computing can seem unusual. The science behind its capabilities often appears counterintuitive because it deviates significantly from the laws governing our everyday experiences. Classical information processing relies on bits, which are either off or on, representing two possible values: 0 or 1. All classical computations can be decomposed into operations involving these binary values.

However, a quantum processor utilizes qubits. These fundamental units can exist in a state of quantum superposition, meaning they are not limited to being either 0 or 1 but can hold both possibilities concurrently. This state isn’t simply a third state but rather a spectrum of probable states where a qubit can embody every possible combination of 0 and 1 to varying degrees.

Nephtali Garrido-Gonzalez explains that the number of possible states representable by a quantum computer increases exponentially with each qubit added. “For instance, two qubits can represent four states simultaneously, three qubits can represent eight states, and so on, growing as 2^n, where n is the number of qubits. This exponential growth is why quantum computing is so appealing for certain calculations.”

Number of Qubits | Possible Independent States |

1 | [0], [1] |

2 | [0, 0], [0, 1], [1, 0], [1, 1] |

3 | [0, 0, 0], [0, 1, 0], [0, 0, 1], [0, 1, 1] [1, 0, 0], [1, 1, 0], [1, 0, 1], [1, 1, 1] |

A common representation of qubits is the Bloch sphere. Visualize the poles of this sphere as our classical 0 and 1. A classical bit must reside at either the north pole (0) or the south pole (1), while qubits in superposition can exist anywhere on the sphere’s surface. This ability opens up a vast array of logical states, far exceeding the binary limitations of classical computers.

The qubit possesses other capabilities that further enhance computational efficiency: The property of entanglement enables a qubit to instantaneously influence the state of another, irrespective of the distance separating them. Entangled particles could be positioned at opposite ends of the universe and would still behave in unison.

Four states can be generated from the maximal entanglement of two qubits. These states are known as Bell states and represent the simplest example of quantum entanglement. Each state is linked to the others and perfectly correlated regardless of distance, making all states “maximally entangled.”

Mathematically, the four states can be represented as:

|Φ⁺⟩ = (|00⟩ + |11⟩) / √2 |

|Φ⁻⟩ = (|00⟩ - |11⟩) / √2 |

|Ψ⁺⟩ = (|01⟩ + |10⟩) / √2 |

|Ψ⁻⟩ = (|01⟩ - |10⟩) / √2 |

In this representation, |0⟩ and |1⟩ are the fundamental states of a qubit, while the + and - symbols indicate superpositions with equal probability but different phases between the components. The factor of 1/√2 serves as a normalization factor, ensuring that the total probability of finding the system in either state remains 1.

While we won’t delve deeply into the mathematical intricacies of Bell states, their fundamental functionality can be summarized as follows:

- For |Φ⁺⟩ and |Φ⁻⟩ Bell states: If one qubit is measured and found to be in state |0⟩, you instantaneously know that the other qubit is also in state |0⟩. Conversely, if the first qubit is measured as |1⟩, the other qubit will also be in state |1⟩.

- For |Ψ⁺⟩ and |Ψ⁻⟩ Bell states: Measuring one qubit as |0⟩ instantly reveals that the other qubit is in state |1⟩. Conversely, if the first qubit is measured as |1⟩, the other qubit will be in state |0⟩.

This extraordinary property can be exploited for teleporting qubits’ states from one location to another, which is crucial for sharing private keys in QKD and in superdense coding—a communication protocol that enables the transmission of two classical bits by sending only one qubit. However, its most prevalent application currently lies in quantum error correction, where the correlation between entangled qubits aids in detecting and rectifying errors without directly measuring the quantum information, thereby preserving the integrity of its quantum state.

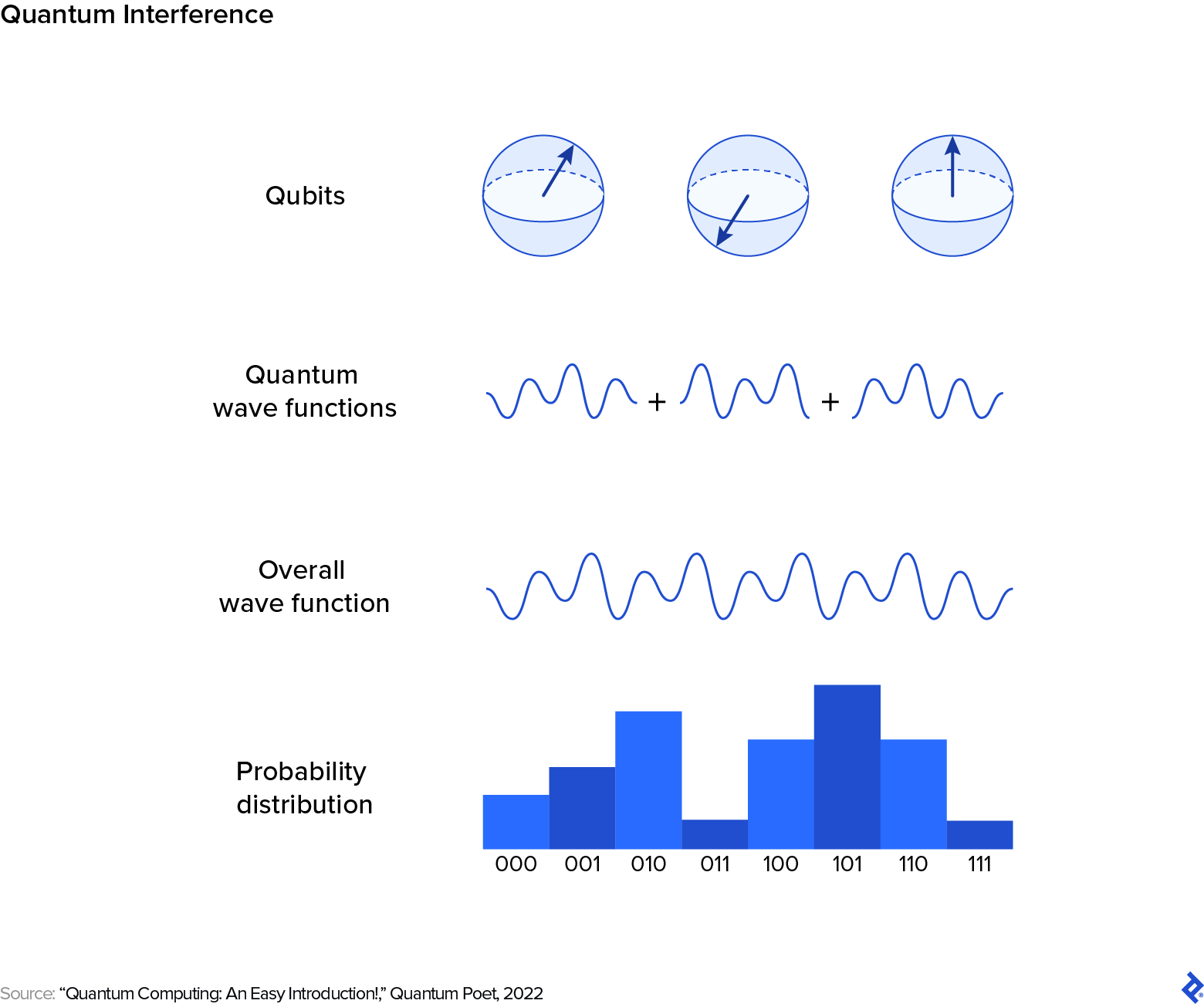

Interference is the third property that grants quantum computing its advantage. Quantum states can be represented as wave functions due to the wave-particle duality inherent in quantum mechanics. Just as quantum superposition allows qubits to exist in a state embodying a continuum between 0 and 1, interference enables these superposed states to interact in ways that can be harnessed for computation.

Imagine two musical notes played simultaneously. Depending on their frequencies (pitches), they can produce different effects. When the frequencies align harmoniously, the sound waves from each note combine to amplify the overall sound, resulting in a pleasant and rich tone. However, if the frequencies clash slightly, they can interfere destructively, producing a dissonant sound. Analogously, a quantum system can be conceived as having multiple states or paths that interfere with one another, much like a complex musical piece comprises multiple notes and interacting harmonies.

“We’ve developed methods to ensure that the wave amplitudes of the qubits that don’t correspond to the desired answer cancel each other out, while those corresponding to the desired outcome are amplified. This process results in a state where the probability of identifying the correct element is significantly high,” says Garrido-Gonzalez, whose work in quantum computing includes building a laser control system for quantum experiments at the University of Sussex. “The precision varies depending on the capabilities of your system. Theoretically, increasing the number of qubits enhances the accuracy of the outcome. However, this introduces additional challenges, such as quantum decoherence, which affects the stability of information in a quantum system once it’s measured.”

In simpler terms, while quantum computers possess the potential to solve problems rapidly, they also require careful management to maintain their accuracy as the complexity—both in terms of the number of qubits and the complexity of the query—increases.

Layers of the Quantum Computing Stack

The layers of the quantum computing stack, resembling the classical stack, consist of several levels of abstraction that facilitate the transition from physical hardware to high-level algorithmic solutions:

- Hardware: At the foundation, quantum computing hardware refers to the physical devices that leverage quantum phenomena to perform calculations. These devices can range from small-scale quantum processors with a handful of qubits to more advanced systems with hundreds or thousands of qubits. Hardware may also encompass technologies like superconducting qubits, trapped ions, topological qubits, or photonic circuits.

- Physical qubits: These are the fundamental building blocks of a quantum computer, representing the quantum counterpart to classical bits. However, physical qubits are susceptible to errors and decoherence, potentially leading to data corruption or loss.

- Quantum error correction: This layer focuses on detecting and correcting errors in quantum data caused by decoherence and noise in physical qubits. It typically involves spreading quantum information across multiple physical qubits and applying algorithms to rectify detected errors and recover the intended quantum state.

- Logical qubits: Logical qubits offer a more stable and accurate means of storing quantum information, achieved through quantum error correction and other strategies that minimize errors. An [instruction set architecture](https://ipo.lbl.gov/quantum-instruction-set-architecture-quasar/#:~:text=As%20quantum%20computing%20matures%2C%20there,instruction%20set%20architecture%20(ISA) outlines the operations executable on these logical qubits, providing a framework for quantum computing tasks.

- Quantum intermediate representation (QIR): QIR serves as a bridge between quantum algorithms and physical hardware, enabling the description of quantum circuits and algorithms in a way that’s compatible with compilers and adaptable to various quantum computing technologies.

- Quantum algorithms: These are specialized instructions or operations that leverage quantum theory—specifically phenomena like superposition, entanglement, and interference—to solve problems efficiently. Notable examples include Shor’s algorithm for integer factorization and the group isomorphism algorithm.

Getting Practical: Hands-on Quantum Computing

A solid grasp of quantum information is essential for starting with quantum software. However, according to Ghassan Hallaq, engineers venturing into the quantum realm don’t need a deep understanding of the physics behind quantum mechanics. “The fundamental concepts are linear algebra, vector spaces, and complex numbers. Within a complex vector space, quantum states are defined as vectors, while matrices represent quantum operations. Linear algebra provides the necessary tools to understand these representations and operations. Complex numbers are also crucial because they are used to describe the probability amplitudes of quantum states,” Hallaq explains.

To supplement the fundamentals covered in this article, Hallaq recommends that newcomers to quantum development explore a free series of courses offered by IBM as additional preparation for working with quantum software. For now, we’ll discuss the available quantum software development kits (SDKs) for quantum computing and then walk through simple quantum development examples using Cirq and TensorFlow Quantum.

Available Kits for Software Development

Developers seeking to program and interact with quantum computers have access to a variety of quantum software development kits and programming frameworks. These resources abstract away the complexities of quantum computing, allowing users to employ higher-level programming languages and libraries to create and execute quantum circuits and algorithms.

Two prominent and readily available quantum SDKs are Cirq and TensorFlow Quantum (TFQ), both developed by Google. Cirq is an open-source library that empowers developers to create, manipulate, and optimize quantum circuits. It’s particularly valuable for researchers and developers working on the fundamental aspects of quantum computing, such as quantum algorithm design, quantum circuit optimization, and low-level quantum hardware control.

TFQ takes a different approach, focusing on integrating quantum computing into machine learning models and workflows. Built on top of TensorFlow, a cornerstone of machine learning and one of the most widely used libraries in the field, TFQ provides a set of tools and abstractions for constructing quantum circuits, simulating quantum computations, and integrating these quantum computations with classical machine learning components.

While both Cirq and TFQ can interface with real quantum computers through different back ends, Google does not offer public access to its quantum infrastructure currently. If you’re looking to test your circuits and algorithms on actual hardware, a popular option is IBM’s Qiskit.

Qiskit aims to be user-friendly and approachable, catering to users without extensive quantum computing backgrounds. It enables developers to write quantum programs using high-level programming languages like Python, offering a wide range of features for circuit construction, optimization, simulation, and visualization. IBM has built a robust ecosystem around Qiskit through partnerships with businesses, research organizations, and academic institutions. Other notable services include Microsoft’s Azure Quantum Development Kit and Amazon’s Braket, each with its unique features and capabilities.

Getting Started With Cirq

Cirq simplifies working with the technical details of quantum hardware platforms, enabling developers to create quantum algorithms and circuits on Google’s hardware. Google provides comprehensive extensive resources to help individuals interested in quantum computing get up to speed quickly.

Let’s begin by examining the code for a basic quantum algorithm. Our goal is to define and manipulate qubits through a sequence of quantum gates and operations. These manipulations occur within a quantum circuit, a structured pathway that guides the evolution of qubits from their initial states to a final measurement.

As mentioned earlier, qubits can exist in a state of superposition, simultaneously embodying both 0 and 1. The first step in constructing our quantum circuit is to define these qubits. In Cirq, qubits are not merely abstract entities; they can be named, arranged linearly, or positioned on a grid, mirroring the potential layouts of physical quantum processors. This flexibility allows for tailoring the circuit’s structure to the specific needs of algorithms or hardware configurations.

There are three primary methods for defining qubits:

cirq.NamedQubit: Qubits are identified by an abstract name.cirq.LineQubit: Qubits are identified by a number within a linear array.cirq.GridQubit: Qubits are identified by two numbers within a rectangular grid.

Here’s an example of how to define qubits using these three methods:

| |

With our qubits defined, we introduce quantum gates—the dynamic elements that modify the state of qubits. Quantum gates are to qubits what operations are to classical bits. In Cirq, a gate is defined as an effect that can be applied to a collection of qubits, represented as transforming them into operations. These operations are the actual events that transpire within the circuit, such as flipping a qubit’s state or entangling two qubits.

In the next example, we’ll define a circuit where two common gates will act on a pair of qubits:

- Pauli-X gate: Often referred to as the bit-flip gate, it serves the same purpose as the classical NOT gate, flipping the state of a qubit: |0⟩ becomes |1⟩, and vice versa.

- Hadamard gate: The Hadamard gate creates superposition. It transforms the basis states |0⟩ and |1⟩ into equal superpositions of both, enabling parallel computation over the superposed states.

After applying the gates, we’ll measure the results. Measurement is crucial because it collapses the quantum state into a classical state, revealing the outcome of the quantum operations performed on the qubits. Without measurement, while the qubits might undergo various transformations, the results of these operations would remain undetermined.

| |

This printed output represents the sequence of operations within the circuit for each qubit:

| |

Let’s break down the output:

- 0 and 1 denote the line (or qubit) numbers.

- X represents the Pauli-X gate applied to qubit q0.

- H represents the Hadamard gate applied to qubit q0 immediately after the Pauli-X gate.

- M indicates a measurement operation. The measurement is shown on both qubits, indicating that the states of both qubits q0 and q1 will be measured at the end of the circuit’s execution.

Now, let’s assume that both qubits start in the state |0⟩. The Pauli-X gate flips q0 from |0⟩ to |1⟩. Subsequently, the Hadamard gate creates a superposition, transforming the state of q0 |1⟩ into a superposition of |0⟩ and |1⟩ with equal probabilities but a phase difference. Upon measurement, q0 can collapse to either |0⟩ or |1⟩. Since q1 remains unaltered in state |0⟩, the potential measurement outcomes for the two qubits are:

- [0,0] with a 50% probability.

- [1,0] with a 50% probability.

The actual output from executing the circuit wouldn’t display these probabilities but rather one of the possible measurement outcomes, determined by the inherent randomness of quantum measurement in superposition states.

While this circuit is quite basic, it demonstrates fundamental quantum computing principles that serve as essential building blocks. For instance, one of the steps in Grover’s search algorithm involves applying a Hadamard gate to each qubit in the system, putting each qubit into a superposition of states.

Executing a Cirq Circuit

So far, we’ve only defined what our circuit should do, not actually run it. To observe actual results, we need to introduce either a quantum simulator or a real quantum computer. Quantum simulators are software tools that emulate the behavior of a quantum computer while still relying on classical computing resources. The simulator executes the circuit a specified number of times and provides the measurement outcomes for each run, allowing for analysis of the probability distribution of the outcomes.

Cirq offers various simulators. For basic circuits, cirq.Simulator is a suitable choice:

| |

After executing our circuit (where one qubit has a Hadamard gate applied) and running it for 1,000 repetitions, you might observe the following measurement output:

- [0,0]: 498 times

- [1,0]: 502 times

These results align with the expected theoretical probabilities.

Running the circuit on a real quantum computer wouldn’t be drastically different, but the results might deviate from those predicted by ideal simulators due to physical noise and errors still prevalent in quantum processors. It would also be more expensive, and you would need to ensure that your circuit is compatible with any hardware constraints, such as the available qubit connections and supported gates.

The choice between a simulator and a real quantum computer often hinges on the development stage and objectives of your project, the circuit’s complexity, and the required level of precision. Initial development, testing, and learning are efficiently conducted on simulators. In contrast, final validation, experiments demonstrating quantum advantage, and investigations into the effects of noise and quantum hardware characteristics necessitate using real quantum processors.

Exploring TensorFlow Quantum

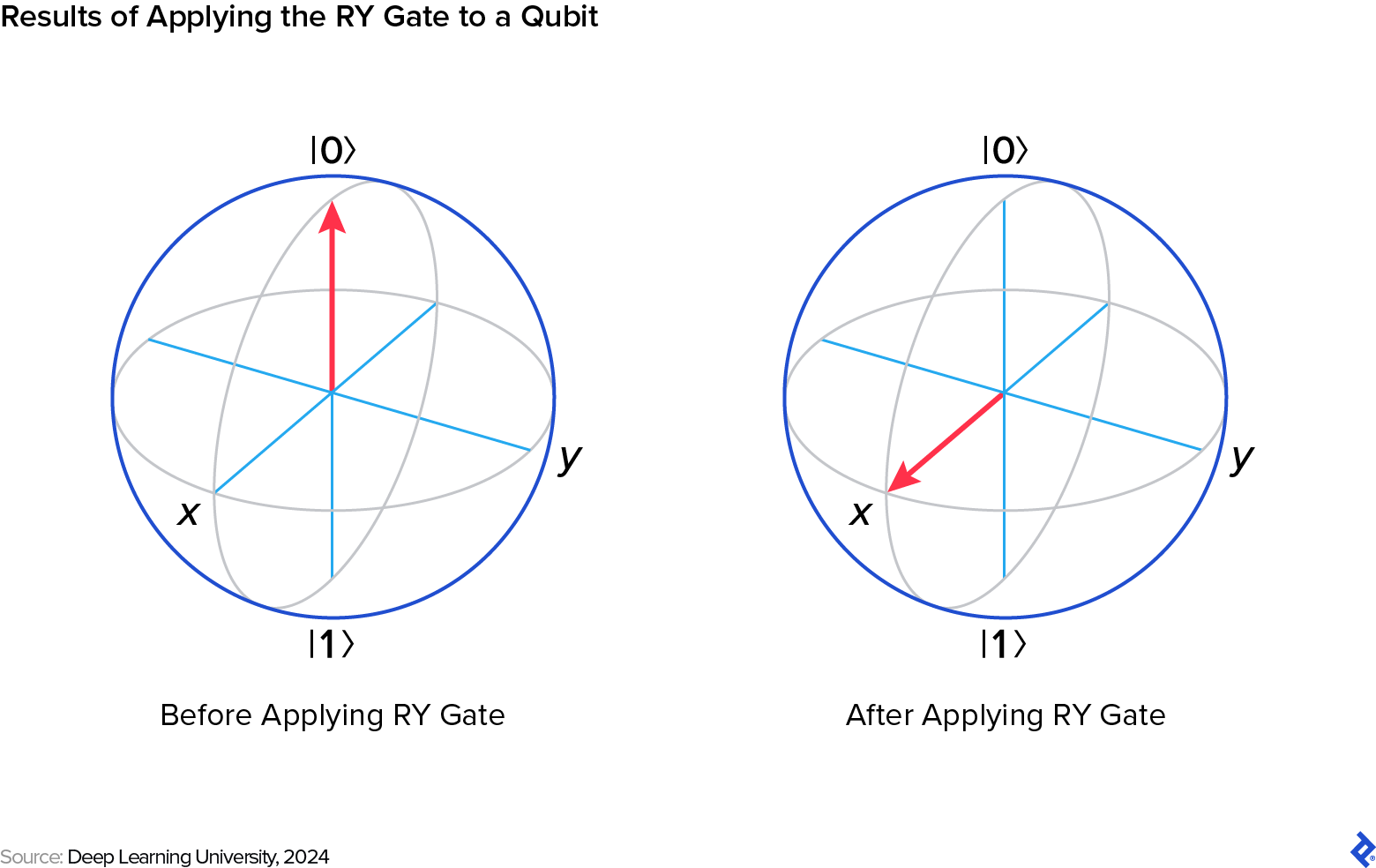

To illustrate TFQ’s capabilities, let’s build on the Cirq example by introducing two new quantum gates: the controlled-NOT (CNOT) gate, crucial for creating entanglement between qubits, and the RY gate, a single-qubit gate that rotates a qubit around the y-axis of the Bloch sphere. By adjusting the rotation angle θ (theta), you can control the probabilities of measuring the qubit in the ∣0⟩ or ∣1⟩ state, enabling a broader and more intricate range of quantum operations.

We start by defining a quantum circuit that applies a Hadamard gate to the first qubit to create a superposition, followed by a rotation using an RY gate. This demonstrates how classical data (the parameter for the RY gate) can be encoded into a quantum state. Finally, we use a CNOT gate to entangle it with the second qubit, creating a Bell state and showcasing the three fundamental properties of quantum computing.

| |

Here’s how our circuit looks at this point:

| |

Here’s a breakdown of the circuit:

- 0 and 1 represent the line numbers corresponding to the first and second qubits, respectively.

- H denotes the Hadamard gate applied to the first qubit (q0), putting it into a superposition state.

- RY(θ) indicates a rotation around the y-axis applied to q0, parameterized by θ (theta). This represents how classical data is encoded into the quantum state using the rotation angle.

- @ and X together symbolize the CNOT gate, with q0 acting as the control qubit and q1 as the target qubit. This gate entangles q0 and q1.

- M indicates measurement operations on both qubits, collapsing their quantum states to classical bits.

Now, let’s incorporate this quantum circuit into a hybrid quantum-classical model that processes classical data (theta) through the quantum circuit and then classifies it using a classical neural network:

| |

The ControlledPQC layer in TFQ allows for using parameterized quantum circuits where classical data can control quantum operations, bridging the gap between classical and quantum computing. The benefits of this integration might not be immediately apparent, as this example only scratches the surface of TFQ’s capabilities and hybrid models. Let’s consider a potential practical application.

In drug discovery, identifying molecules that can bind to specific protein targets is a critical step known as a complex and computationally intensive task. This process involves analyzing vast databases of chemical compounds to predict their interactions with biological targets, which is crucial for pinpointing promising drug candidates. The high-dimensional nature of molecular data and the complex, nonlinear interactions between molecules and biological targets make this task quite challenging for classical machine learning models.

However, by employing an RY gate in a quantum circuit like the one above to encode classical molecular data (such as molecular fingerprints) into quantum states, we can map the high-dimensional data into a state that reflects the molecule’s characteristics.

Then, by applying quantum operations to these encoded states, we can perform computations that explore the complexity of the molecular data. For instance, this step could involve using quantum interference to highlight patterns indicative of a molecule’s binding affinity to the target protein.

The quantum-processed data is then fed into a classical neural network, which classifies the molecules based on their predicted binding affinity. The quantum preprocessing step aims to enhance the features, making it easier for the classical neural network to identify promising drug candidates.

This approach could substantially accelerate the initial screening process for drug candidates, enabling researchers to focus on investigating the most promising compounds.

While we’ve covered a simple example, TFQ offers a rich set of tools and abstractions for constructing more complex hybrid quantum-classical models, empowering developers to explore the potential of quantum computing for enhancing machine learning algorithms and models.

Achieving Quantum Supremacy

Quantum computing is within reach for any developer eager to learn and experiment. However, several challenges must be addressed before we can fully realize its potential. Even with powerful algorithms and techniques available, current hardware lacks the stability to achieve “quantum supremacy”—the theoretical point at which a quantum algorithm solves a problem that’s either impossible or would take an impractical amount of time to solve using the best-known classical algorithms for that task.

One of the most pressing issues is the current error rates and limited coherence times of quantum hardware. Qubits are highly susceptible to external disturbances and decoherence, leading to errors and noise that affect quantum computations.

Researchers are actively pursuing error correction strategies and approaches to achieve fault-tolerant quantum computing. There’s also a concerted effort to develop materials and designs for quantum hardware that extend qubit coherence times and minimize error rates.

Despite these challenges, quantum computing remains an incredibly promising field. Ongoing research and development are pushing the boundaries of computing as we know it. Researchers are exploring the potential of quantum communication](https://www.technologyreview.com/2019/02/14/103409/what-is-quantum-communications/) and quantum networking, which could enable secure and tamper-proof communication channels and distributed quantum computing capabilities. Integrating quantum computing with emerging technologies such as machine learning and artificial intelligence could lead to groundbreaking advancements. Similarly, hybrid quantum-classical models and quantum-enhanced algorithms are expected to bring breakthroughs in fields like computer vision, natural language processing, and scientific simulations.

As the quantum revolution unfolds, businesses, researchers, and policymakers must stay informed about and engaged with this rapidly evolving field. By embracing quantum computing and fostering a culture of innovation, organizations can position themselves to harness the transformative power of this technology and unlock new frontiers in product development and technological progress.