When a web application reaches a certain age and size, splitting it into smaller, self-contained parts and extracting services can become necessary. This can be driven by the need to speed up testing, enable independent deployments of different app sections, or establish clear boundaries between subsystems. Service extraction presents software engineers with crucial decisions, including the technology stack for the new service.

This post recounts our experience extracting a new service from our monolithic Toptal Platform. We’ll delve into our chosen tech stack, the rationale behind it, and the challenges we encountered during implementation.

Our Toptal Chronicles service manages all user actions on the Toptal Platform, essentially functioning as a log of user activities. Each action, like publishing a blog post or approving a job, generates a new log entry.

While originating from our Platform, Chronicles is inherently independent and can integrate with any application. This independence is why we’re sharing our process and the hurdles our engineering team overcame during the transition.

Several factors motivated our decision to extract the service and upgrade the stack:

- We aimed to enable other services to log events viewable and usable elsewhere.

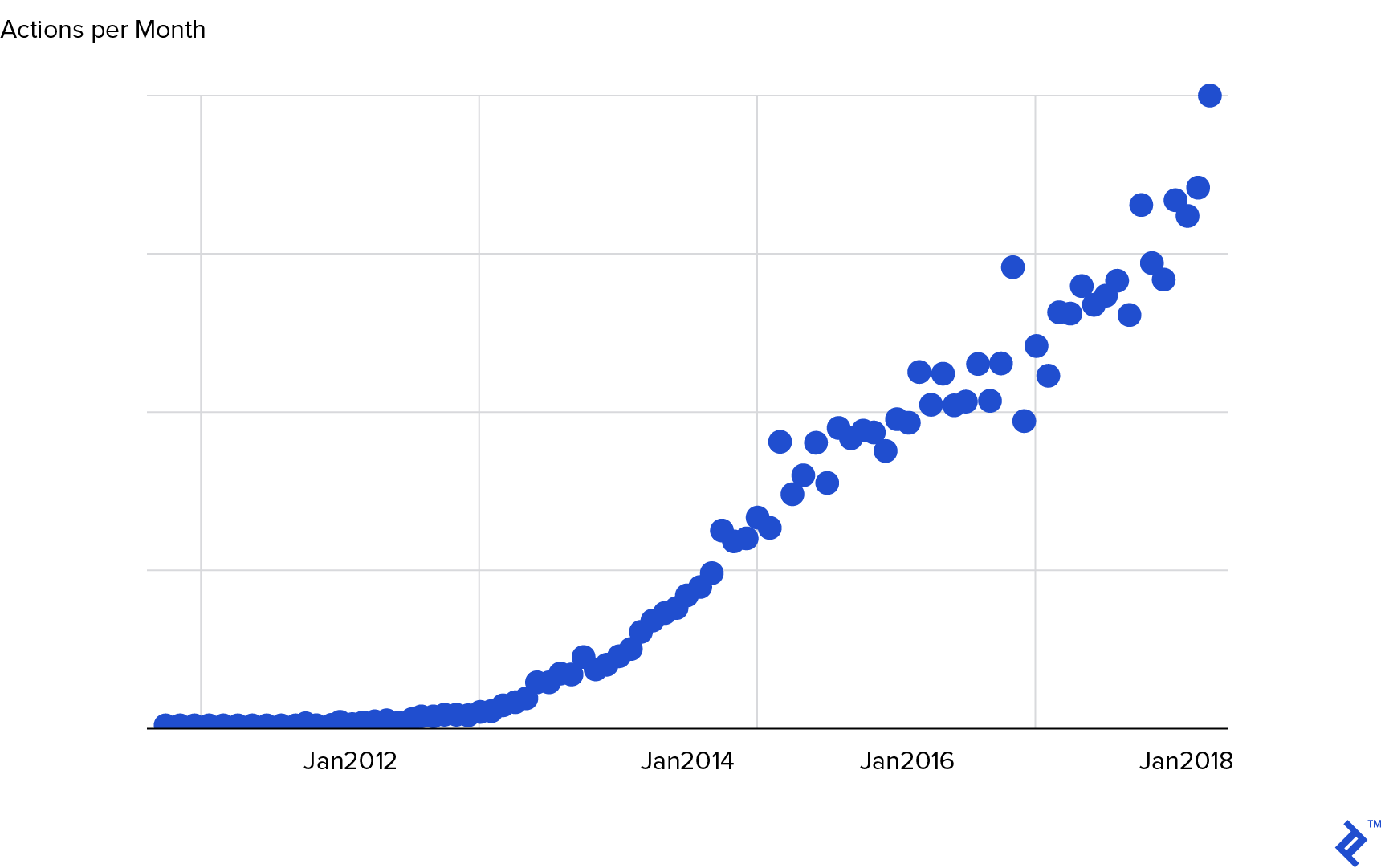

- The database tables storing history records were growing rapidly and unevenly, leading to high operational costs.

- We recognized a significant technical debt in the existing implementation.

While appearing straightforward initially, alternative tech stacks often bring unforeseen challenges, which is what this article will explore.

Architecture Overview

Chronicles comprises three relatively independent parts, each running in separate Docker containers:

- Kafka consumer: A lightweight Karafka-based Kafka consumer that receives entry creation messages and queues them in Sidekiq.

- Sidekiq worker: Processes Kafka messages and creates corresponding entries in the database table.

- GraphQL endpoints:

- Public endpoint: Exposes the entry search API used for various Platform functions (e.g., rendering comment tooltips, displaying job change history).

- Internal endpoint: Enables tag rule and template creation from data migrations.

Initially, Chronicles connected to two databases: its own for storing tag rules and templates, and the Platform database for user actions, tags, and taggings. During extraction, we migrated data from the Platform database and severed the connection.

Initial Plan

We initially opted for Hanami and its default ecosystem (hanami-model with ROM.rb, dry-rb, hanami-newrelic, etc.). This “standard” approach promised minimal friction, rapid implementation, and readily available solutions for potential issues. The hanami ecosystem offered maturity, popularity, and active maintenance by respected Ruby community members.

Since a significant portion of the system, like the GraphQL Entry Search endpoint and CreateEntry operation, was already implemented on the Platform side, we planned to reuse much of that code in Chronicles without modification. This was another reason for not choosing Elixir, as it wouldn’t allow for direct code reuse.

Rails felt excessive for this relatively small project, particularly features like ActiveSupport, which wouldn’t provide significant benefits for our needs.

When the Plan Goes South

Despite our best efforts, several factors led us to deviate from the initial plan: our limited experience with the chosen stack, genuine issues with the stack itself, and our non-standard two-database setup. Ultimately, we abandoned hanami-model and then Hanami entirely, replacing it with Sinatra.

Sinatra, a well-maintained library with over a decade of history and widespread popularity, became our choice. Its familiarity within the team ensured ample hands-on experience.

Incompatible Dependencies

At the time of Chronicles’ extraction in June 2019, Hanami lacked compatibility with the latest dry-rb gems. Hanami 1.3.1 (the latest then) only supported dry-validation 0.12, while we needed dry-validation 1.0.0 for its contract feature. Additionally, Kafka 1.2 was incompatible with dry gems, forcing us to use the repository version. Currently, we use 1.3.0.rc1, which supports the latest dry gems.

Unnecessary Dependencies

The Hanami gem brought along many dependencies we didn’t intend to use, including hanami-cli, hanami-assets, hanami-mailer, hanami-view, and even hanami-controller. The hanami-model readme also revealed that it supported only one database by default, while ROM.rb, the foundation of hanami-model, offered out-of-the-box multi-database configurations.

Ultimately, Hanami and hanami-model felt like unnecessary layers of abstraction.

Consequently, ten days after the first substantial PR for Chronicles, we replaced hanami with Sinatra. While pure Rack was also an option due to our simple routing needs (four “static” endpoints), we opted for the slightly more structured Sinatra, which proved to be a perfect fit. If you are interested in learning more about this, check out our Sinatra and Sequel tutorial.

Dry-schema and Dry-validation Misunderstandings

Mastering dry-validation’s intricacies and proper usage took time and experimentation.

| |

This snippet shows multiple, slightly different ways of defining the url parameter. Some are equivalent, while others are nonsensical. Initially, we struggled to differentiate between these definitions due to our limited understanding, resulting in a somewhat chaotic first version of our contracts. Over time, we gained proficiency in reading and writing DRY contracts, resulting in consistent and elegant code—beautiful, even. We’ve even extended contract validation to our application configuration.

Problems with ROM.rb and Sequel

ROM.rb and Sequel’s differences from ActiveRecord were expected. Our initial assumption of easily copying code from the Platform, which heavily relied on ActiveRecord, proved incorrect. We had to rewrite almost everything in ROM/Sequel, with only small, framework-agnostic code snippets being reusable. This process brought its share of frustrating issues and bugs.

Filtering by Subquery

For instance, figuring out subqueries in ROM.rb/Sequel took considerable effort. What would be a simple scope.where(sequence_code: subquery) in Rails became more involved in Sequel: not that easy.

| |

Instead of a concise base_query.where(sequence_code: bild_subquery(params)), we ended up with lengthy code, raw SQL fragments, and multiline comments explaining the reasons behind this verbosity.

Associations with Non-trivial Join Fields

The entry relation (representing the performed_actions table) uses the sequence_code column for joining with *taggings tables, despite having a primary id field. While straightforward in ActiveRecord:

| |

Replicating this in ROM was possible:

| |

However, this seemingly correct code would compile but fail during runtime:

| |

Fortunately, the differing types of id and sequence_code resulted in a PostgreSQL type error. Had they been the same, debugging would have been significantly more challenging.

Since entries.join(:access_taggings) failed, we tried explicitly specifying the join condition as entries.join(:access_taggings, performed_action_sequence_code: :sequence_code), as suggested in the documentation:

| |

This, however, resulted in :access_taggings being incorrectly interpreted as the table name. Replacing it with the actual table name:

| |

While this finally worked, it introduced a leaky abstraction, as table names ideally shouldn’t leak into application code.

SQL Parameter Interpolation

Chronicles’ search feature allows users to search by payload using queries like {operation: :EQ, path: ["flag", "gid"], value: "gid://plat/Flag/1"}, where path is always an array of strings and value can be any valid JSON value.

In ActiveRecord, this translates to: this

| |

In Sequel, properly interpolating :path proved difficult, forcing us to resort to: that

| |

While path undergoes validation to ensure it contains only alphanumeric characters, this code snippet highlights the awkwardness we encountered.

Silent Magic of ROM-factory

We used the rom-factory gem to streamline model creation in tests. However, we encountered unexpected behavior several times. Can you identify the issue in this test?

| |

The expectation itself is not the problem.

The issue lies in the second line, which fails due to a unique constraint validation error. This occurs because the Action model doesn’t have an action attribute. The correct attribute is action_name. The correct way to create actions would be:

| |

The mistyped attribute was silently ignored, defaulting to the factory’s default (action_name { 'created' }). This led to a unique constraint violation when attempting to create two identical actions. This issue recurred multiple times, proving quite cumbersome.

Fortunately, this was fixed in version 0.9.0. Dependabot automatically submitted a pull request with the library update, which we merged after fixing several mistyped attributes in our tests.

General Ergonomics

This example illustrates the situation effectively:

| |

This difference becomes even more pronounced in more complex scenarios.

The Good Parts

Despite the challenges, our journey also had numerous positive aspects that far outweighed the negatives, making the entire endeavor worthwhile.

Test Speed

Running the entire test suite locally takes a mere 5-10 seconds, as does RuboCop. While CI takes longer (3-4 minutes), the ability to run everything locally minimizes the impact, as CI failures become less frequent.

The guard gem has become usable again. Imagine being able to write code and run tests on every save, receiving instant feedback. This was unimaginable when working with the Platform.

Deploy Times

Deploying the extracted Chronicles app takes just two minutes. While not exceptionally fast, it’s still an improvement. Frequent deployments amplify the benefits of even small time savings.

Application Performance

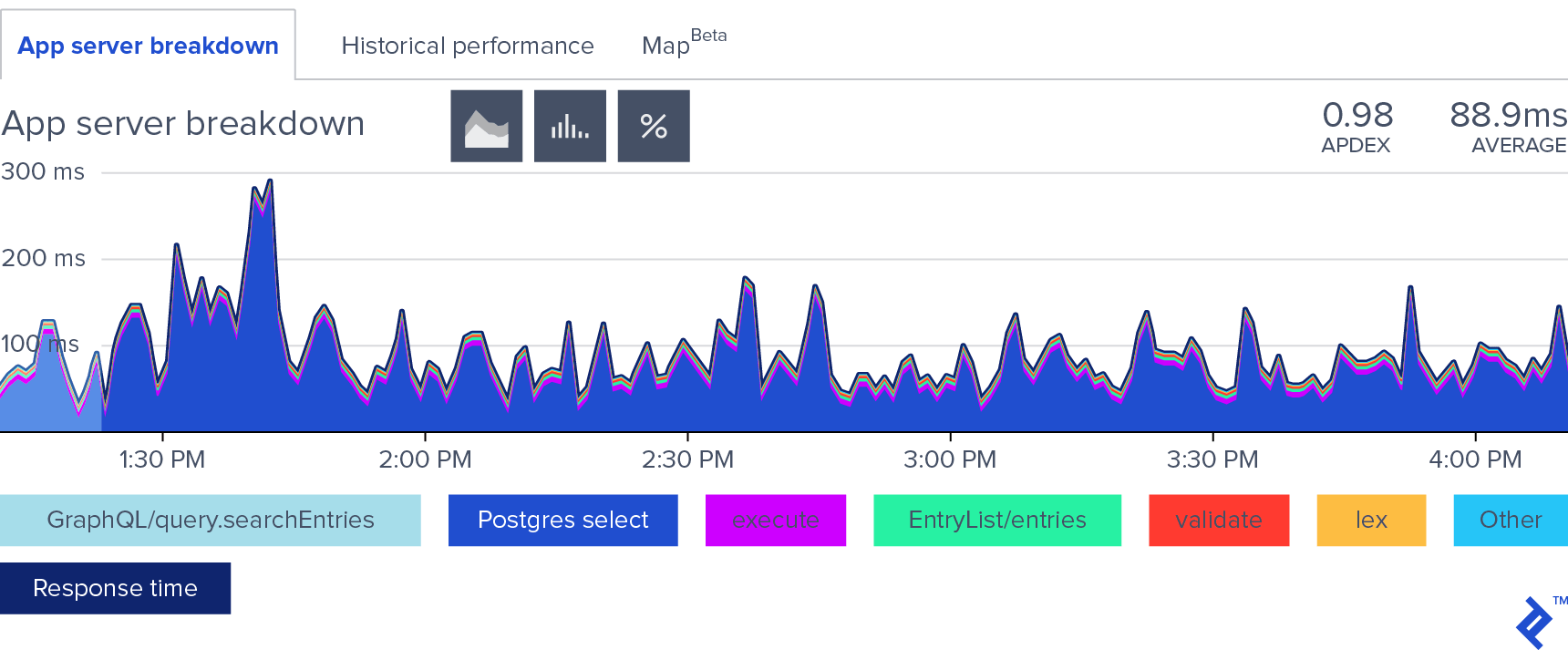

Chronicles’ most performance-critical aspect is Entry search. With about 20 places in the Platform back end fetching history entries from Chronicles, its response time contributes to the Platform’s 60-second response time budget.

Despite the massive actions log (over 30 million rows and growing), the average response time is less than 100ms, as illustrated in this chart:

With 80-90% of the app’s time spent in the database, this demonstrates a healthy performance profile.

While some slow queries can take up to tens of seconds, we have a plan to eliminate them, further improving the extracted app’s performance.

Structure

dry-validation has proven to be a powerful and versatile tool for our requirements. By passing all external input through contracts, we ensure data integrity and well-defined types.

The need for to_s.to_sym.to_i calls in application code is eliminated, as data is cleansed and typecast at the app’s boundaries. This effectively brings the sanity of strong typing to the dynamic world of Ruby. We highly recommend it.

Final Words

Choosing a non-standard stack turned out to be more complex than anticipated. We carefully considered various factors: the monolith’s existing stack, the team’s familiarity with the new stack, and the chosen stack’s maintenance status.

Despite meticulous planning and initially opting for the standard Hanami stack, the project’s unique technical requirements forced us to reconsider. We eventually settled on Sinatra and a DRY-based stack.

Would we choose Hanami again for a similar app extraction? Probably yes. With our current knowledge of the library’s strengths and weaknesses, we could make more informed decisions from the outset. However, a plain Sinatra/DRY.rb app would also be a strong contender.

Ultimately, exploring new frameworks, paradigms, and programming languages provides valuable insights and fresh perspectives on our existing tech stack. Expanding our knowledge of available tools allows us to make better-informed decisions and choose the most appropriate tools for our applications.