Traditional views regarding inversion of control (IoC) often create a distinct division between two approaches: the service locator and dependency injection (DI).

Almost every project I’ve come across utilizes a DI framework. Developers are drawn to them because they encourage loose coupling between components and their dependencies (typically achieved through constructor injection) with minimal to no boilerplate code. Although this is beneficial for rapid development, some argue that it can make code challenging to trace and debug. The “magic” behind the scenes usually relies on reflection, which can introduce a whole new set of issues.

This article explores an alternative pattern suitable for Java 8+ and Kotlin codebases. This approach retains most DI framework benefits while maintaining the simplicity of a service locator, all without external tools.

Motivation

- Eliminate external dependencies

- Avoid reflection

- Encourage constructor injection

- Minimize runtime behavior

An example

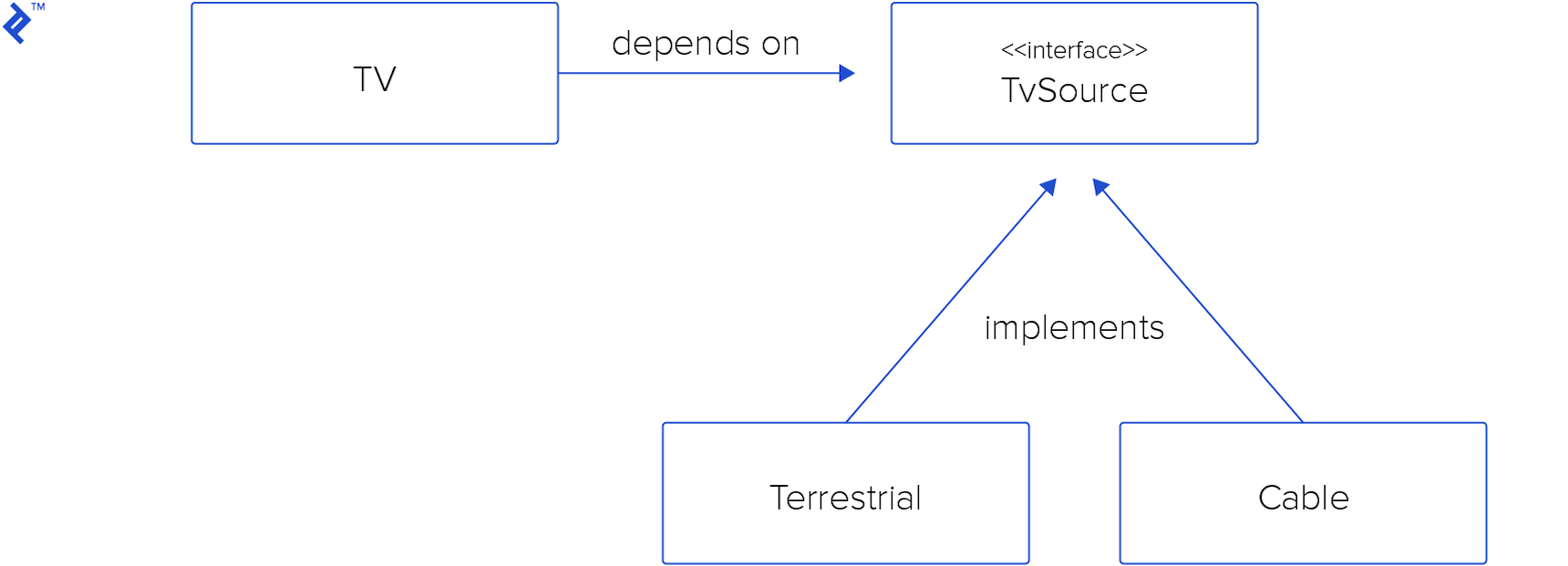

Let’s model a TV implementation with various content sources. We aim to build a device that receives signals from different sources (e.g., terrestrial, cable, satellite). The class hierarchy will look like this:

Let’s start with a traditional DI implementation using a framework like Spring:

| |

Observations:

- The TV class relies on a TvSource. An external framework recognizes this and injects a concrete implementation (Terrestrial or Cable).

- Constructor injection simplifies testing by easily building TV instances with alternative implementations.

While this is a good start, a DI framework might be overkill for this scenario. Some developers have reported debugging difficulties with construction problems (lengthy stack traces, untraceable dependencies). Additionally, our client has indicated longer than expected manufacturing times, and our profiler reveals slowdowns in reflective calls.

One alternative is the Service Locator pattern – straightforward, reflection-free, and potentially suitable for our small codebase. Another is to leave the classes untouched and handle dependency location externally.

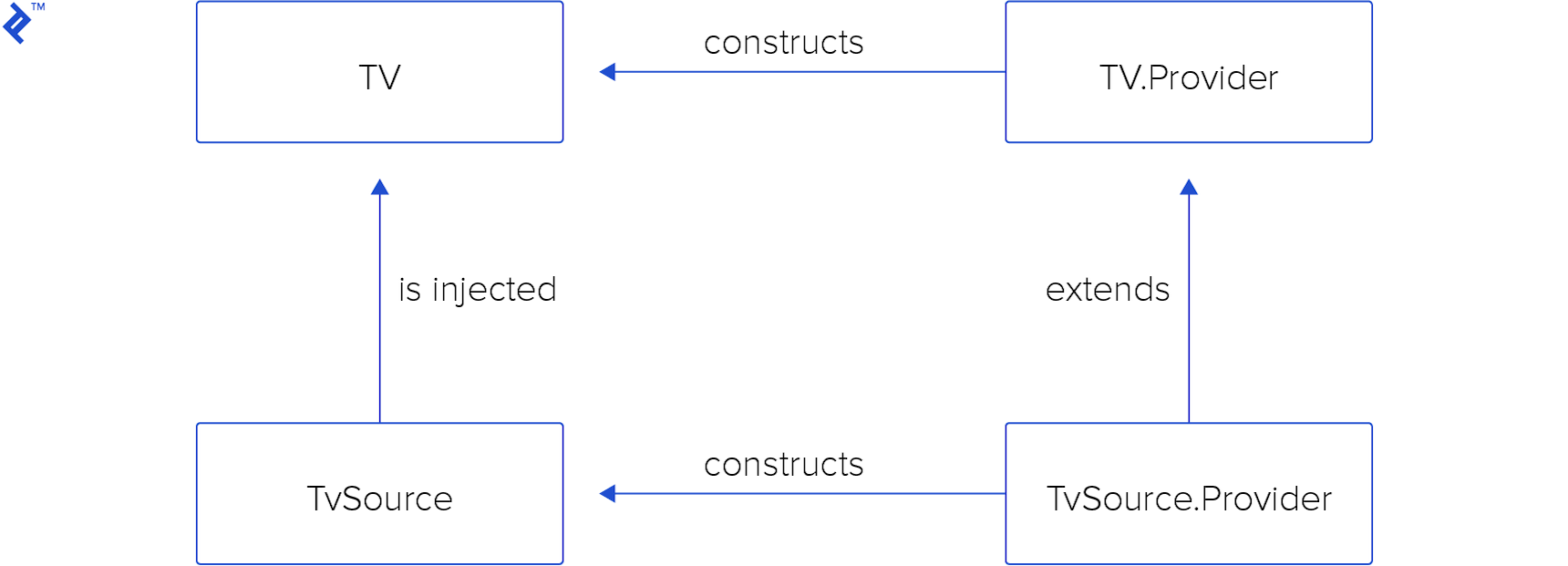

After considering various options, we’ll implement a hierarchy of provider interfaces. Each dependency will have a provider solely responsible for locating dependencies and constructing an injected instance. We’ll make the provider an inner interface for convenience and call it Mixin Injection since each provider mixes with others to locate its dependencies.

The rationale behind this structure is elaborated in the Details and Rationale section. Here’s the short version:

- It separates dependency location behavior.

- Extending interfaces avoids the diamond problem.

- Interfaces have default implementations.

- Missing dependencies are caught during compilation.

The following diagram illustrates the interactions between dependencies and providers. The implementation is shown below, along with a main method demonstrating dependency composition and TV object construction. You can find a more detailed example on this GitHub.

| |

Key points:

- The TV class relies on a TvSource without knowing its concrete implementation.

- TV.Provider extends TvSource.Provider, needing the tvSource() method to build a TvSource (usable even if not implemented there).

- Terrestrial and Cable sources are interchangeable for the TV.

- Terrestrial.Provider and Cable.Provider interfaces provide concrete TvSource implementations.

- The main method uses a concrete MainContext implementation of TV.Provider to get a TV instance.

- The program requires a TvSource.Provider implementation at compile time to instantiate a TV (Cable.Provider serves as an example).

Details and Rationale

We’ve seen the pattern in action and some of its reasoning. While it’s not a perfect solution, I believe it surpasses the service locator in most aspects. Compared to DI frameworks, however, we must weigh the benefits against the added boilerplate code.

Providers Extend Others to Locate Dependencies

Extending providers binds dependencies, providing a basis for static validation and preventing invalid contexts.

A service locator pain point is the generic GetService<T>() method that resolves dependencies without compile-time guarantees, potentially leading to runtime failures.

DI doesn’t fully address this either. Dependency resolution usually happens through reflection, hidden from the user and prone to runtime errors if dependencies aren’t met. While tools like IntelliJ’s CDI (paid version only) offer some static verification, only Dagger with its annotation preprocessor seems to inherently solve this.

Classes Maintain Constructor Injection

While not mandatory, this is highly favored by developers. It allows you to instantly understand a class’s dependencies by looking at its constructor and facilitates unit testing with mock dependencies.

This doesn’t mean other patterns are unsupported. In fact, Mixin Injection can simplify constructing complex dependency graphs for testing because you only need to implement a context class extending your subject’s provider. The MainContext above, with default implementations for all interfaces, demonstrates this with an empty implementation. Overriding a provider method is enough to replace a dependency.

Let’s examine a test for the TV class. Instead of calling the constructor, it uses the TV.Provider interface to instantiate a TV. We need to implement TvSource.Provider ourselves since it lacks a default implementation.

| |

Now, let’s introduce another dependency to the TV class: CathodeRayTube. This decouples the display technology from the TV implementation, allowing for future upgrades (LCD or LED).

| |

The previously written test still compiles and passes. Adding a new dependency to the TV didn’t break anything because we also provided a default implementation. This means we can use the real implementation without mocking and achieve any level of mock granularity in our tests.

This is useful when mocking specific parts of a complex class hierarchy (e.g., only the database access layer) and enables easy setup of sociable tests sometimes preferred over isolated tests.

Regardless of preference, this pattern allows you to adapt your testing strategy to different situations.

No External Dependencies

The code doesn’t rely on external components, which is crucial for projects with size or security restrictions. This also enhances interoperability as frameworks don’t need to commit to a specific DI framework. While efforts like JSR-330 Dependency Injection for Java Standard in Java aim to mitigate compatibility issues, they aren’t always sufficient.

Reflection-Free

Unlike DI implementations that often rely on reflection (except for Dagger 2), service locators and Mixin Injection don’t. This avoids the performance overhead of scanning modules, resolving dependency graphs, and reflectively constructing objects during application startup.

Similar to the registration step in the service locator pattern, Mixin Injection requires you to write code for instantiating services. This eliminates reflective calls, resulting in faster and more straightforward code.

Two notable projects, Graal’s Substrate VM and Kotlin/Native, benefit from avoiding reflection by compiling to native bytecode. This requires explicit declaration of reflective calls in a JSON file that is hard to write (for Graal), which can be cumbersome to maintain and refactor. Mixin Injection sidesteps this by avoiding reflection altogether, paving the way for native compilation benefits.

Minimal Runtime Behavior

The dependency graph is constructed incrementally by implementing and extending required interfaces. Each provider sits beside its concrete implementation, bringing order and logic reminiscent of the Mixin or Cake patterns.

The MainContext class deserves mention here. As the root of the dependency graph, it holds the overall picture. It includes all provider interfaces and plays a crucial role in enabling static checks. Removing Cable.Provider from its implements list in our example illustrates this:

| |

The compiler catches the error because the application doesn’t specify a concrete TvSource. Service locators and reflection-based DI might miss this until runtime, even with passing unit tests. This static verification, along with other benefits, outweighs the overhead of writing boilerplate code for this pattern.

Catching Circular Dependencies

Let’s revisit the CathodeRayTube example and introduce a circular dependency by injecting a TV instance:

| |

The compiler flags this cyclic inheritance, preventing us from defining this relationship. Many frameworks fail at runtime in such cases, leading developers to workarounds that just mask the problem. Although this anti-pattern exists in the wild, it usually indicates poor design. The compilation error encourages us to seek better solutions before it’s too late.

Simple Object Construction

A key argument for SL over DI is its simplicity and ease of debugging. The examples demonstrate that instantiating a dependency is just a chain of provider method calls. Tracing a dependency back to its source is as simple as stepping into the method calls. Debugging becomes easier than both alternatives because you can pinpoint where dependencies are instantiated directly from the provider.

Service Lifetime

You might have noticed that this implementation doesn’t address service lifetimes. All calls to provider methods create new objects, making it similar to Spring’s Prototype scope.

While important, this discussion is beyond the scope of this article. The goal was to present the pattern’s essence without getting bogged down in details. A production-ready implementation would need to address service lifetimes.

Conclusion

Whether you’re accustomed to dependency injection frameworks or prefer writing your own service locators, this alternative is worth exploring. Consider adopting this mixin-based approach to potentially make your code safer, cleaner, and easier to understand.