It’s highly likely that you’ve come across numerous instances of native advertising without even realizing it. These ads have become ubiquitous, making them increasingly difficult to detect.

“Hold on, there’s something off about this cheeseburger…” This article aims to shed light on native advertising, exploring its definition, the reasons behind its controversial nature, and showcasing some noteworthy examples—both impressive and downright awful.

Defining Native Advertising

In essence, native advertising involves paid content. Whether it’s articles, infographics, videos, or any other form of content, if a creator can produce it, companies are willing to pay for it, and publishing platforms are ready to promote it.

Now, you might wonder about the distinction between native advertising and advertorials. To be considered true native advertising, the content needs to seamlessly integrate with the publication’s established editorial style, tone, and provide information that aligns with the audience’s expectations.

These characteristics make native advertisements particularly elusive, as they blend remarkably well with the organic content. Adding to the challenge is the lack of standardized guidelines on labeling these ads, resulting in inconsistent transparency across publications.

It’s important to differentiate native advertising from content advertising. The frequent overlap and name similarity between the two often lead to confusion.

«Need assistance with your ads? Explore our (complimentary!) All-Star Playbook to Online Advertising»

The Controversy Surrounding Native Advertising

“Avoid trickery and refrain from upsetting your audience.”

This sage advice comes from Eric Goeres, Director of Innovation at Time magazine, during his address at the recent Contently Summit. Participating in the “Truth in Advertising” panel, Goeres emphasized the significance of maintaining trust between publishers and their readership. He cautioned against jeopardizing this trust for short-term gains through deceptive advertising practices.

Brands and advertisers are drawn to native ads due to their significantly higher click-through rates and increased engagement compared to conventional advertisements. However, this enthusiasm isn’t universally shared, particularly among consumers.

Several professional bodies have raised concerns regarding the often ambiguous nature of native advertising. The Federal Trade Commission is contemplating regulatory measures for brands utilizing native ads, aiming to ensure consumer benefit. Similarly, the American Society of Magazine Editors has advocated for greater transparency and oversight within the realm of native advertising.

The potential for native advertising to erode public trust poses a significant concern for publishers. The question arises: if a publication like The New York Times publishes a “story” sponsored by a company like Dell, can it maintain objectivity in its reporting on Dell? This dilemma highlights the challenges publishers face today.

Native Advertising: By the Numbers

Before delving into examples, let’s familiarize ourselves with some notable the state of the native advertising landscape:

- Nearly half of consumers lack awareness about native advertising.

- Among those aware, 51% harbor skepticism.

- Three-quarters of publishers incorporate native advertising on their sites.

- 90% of publishers are either running or planning native ad campaigns.

- 41% of brands utilize native advertising within their promotional strategies.

Exemplary Native Advertising: 5 Stellar Examples

Having established that native advertising is here to stay (at least for now), let’s explore some of its finest (and worst) implementations.

1. The Onion’s “Woman Going to Take Quick Break After Filling Out Name, Address on Tax Forms”

Renowned for its satirical wit, The Onion also demonstrates a firm grasp of native advertising, as evident in this widely recognized example.

Admittedly, this example blurs the lines of our native advertising definition. While The Onion created this content specifically for H&R Block, rather than Block directly publishing on the site, its content and placement still qualify it as native advertising (at least in my view).

During its 2012 publication, the article was surrounded by traditional H&R Block banner ads. Even if those ads received minimal clicks (as you’re 475 times more likely to survive a plane crash than click a banner ad, according to Solve Media), the campaign significantly boosted brand recognition.

Why It Works

Despite not directly focusing on H&R Block, the content cleverly tackles the typically dull topic of taxes in a humorous, relatable, and highly entertaining manner. This creates a positive association with the brand. The native ad even injects humor by incorporating an endorsement from The Onion’s fictitious “Publisher Emeritus” T. Herman Zweibel within the sponsored content box.

While the banners acted as calls to action, the primary objective was to amplify H&R Block’s brand awareness—a goal this native advertising example achieved remarkably well.

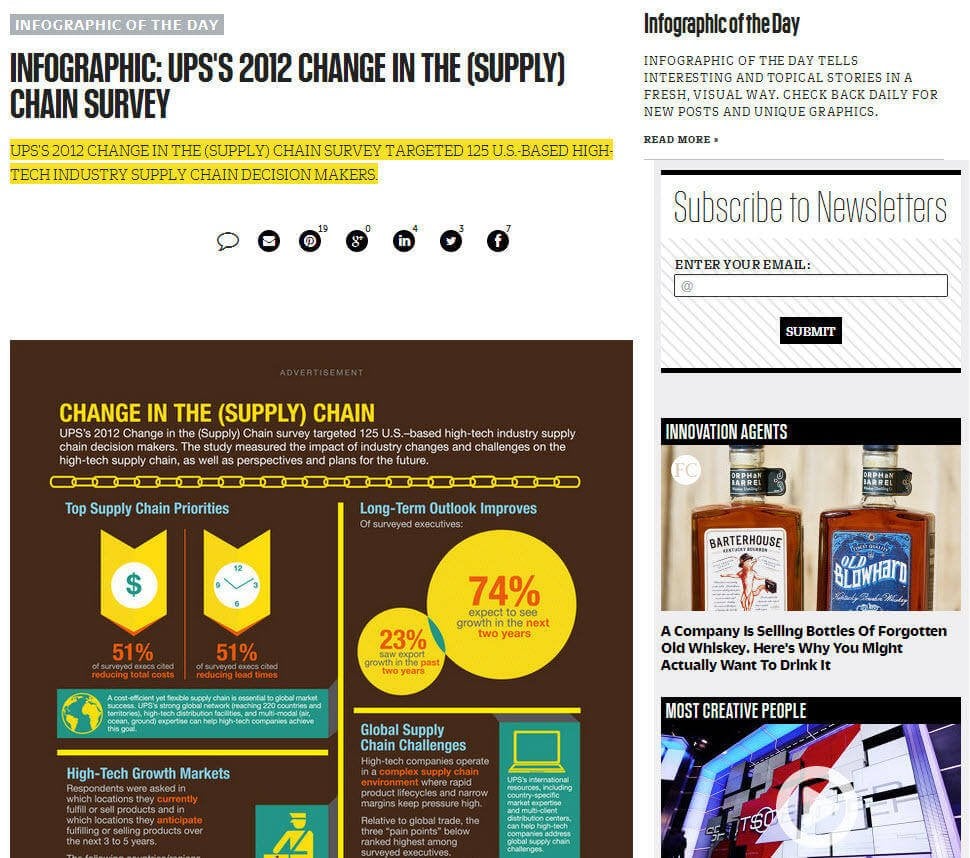

2. Fast Company’s “Infographic: UPS’s 2012 Change in the (Supply) Chain Survey”

This infographic showcases UPS’s supply chain management innovations and exemplifies effective native advertising. While not the most visually stunning infographic, it effectively conveys its message.

Why It Works

This infographic seamlessly integrates with Fast Company’s typical content, making it a prime example of native advertising. The subtle “Advertisement” tag at the top is easy to overlook. The use of UPS’s signature brown and yellow color scheme further reinforces brand messaging subtly. By employing the trusted “problem/solution” format, the infographic successfully promotes UPS’s services.

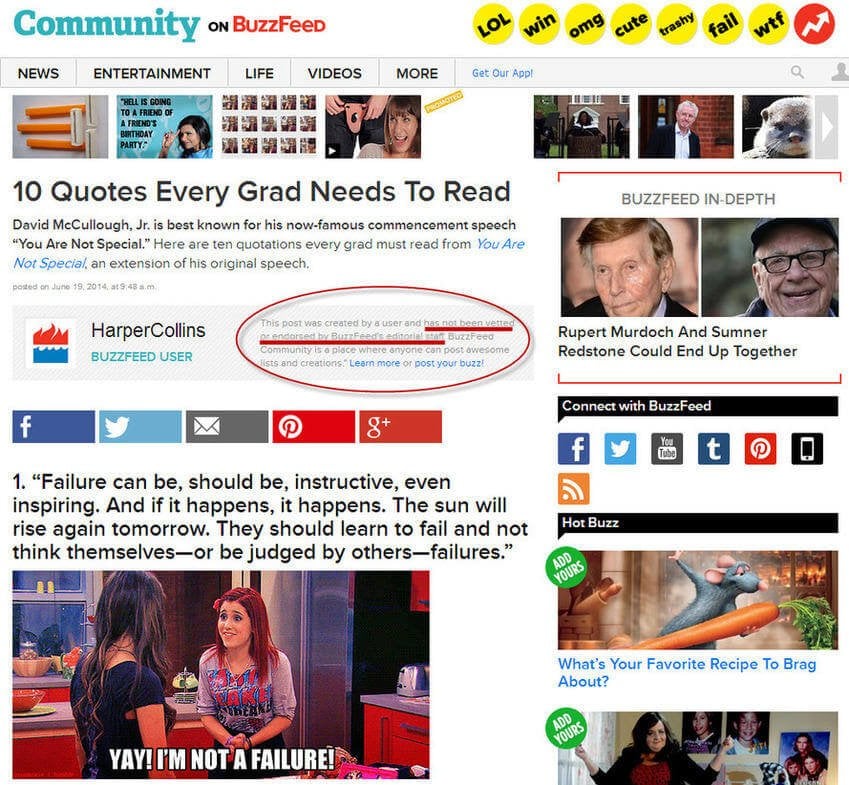

3. BuzzFeed’s “10 Quotes Every Grad Needs to Read”

BuzzFeed, alongside Upworthy, reigns supreme in the realm of viral content creation. It’s no surprise that the platform would leverage its massive readership by offering opportunities to deep-pocketed sponsors. A prime example is the BuzzFeed “Community” pages, featuring brands like publishing powerhouse HarperCollins:

As depicted, BuzzFeed clearly labels posts within the Community section as “not been vetted or endorsed by BuzzFeed’s editorial staff.” This implies that brands like HarperCollins are paying for exposure to BuzzFeed’s audience. Apart from the prominent HarperCollins logo above the social sharing buttons, there’s minimal distinction from regular BuzzFeed content.

Why It Works

The success of this native advertising example hinges on its timeliness. Firstly, its late June publication coincides perfectly with graduation season. Secondly, it capitalizes on the virality of teacher David McCullough, Jr.’s renowned “You Are Not Special” commencement speech.

Adhering to BuzzFeed’s popular animated .GIF/listicle format ensures easy consumption. The headline is impeccably tailored to resonate with BuzzFeed’s audience. The connection between the client (a major publishing house) and the content remains subtle, relying on the implicit association between graduates and books. This “soft sell” approach is more palatable to audiences compared to forceful product placements.

4. Forbes’ “Should You Accept Your Employer’s Pension Buyout Offer?”

Articles like this have been a staple on Forbes for years. As the publication transitioned from a full-time staff model to a contributor-driven one, it’s unsurprising to see native advertising from financial institutions like this piece by Fidelity Investments.

This serves as a particularly strong example of native advertising. While clearly branded and presenting a specific perspective, the post offers valuable content. It delves into the advantages and disadvantages of both monthly and lump-sum pension buyout options, supported by concrete data on inflation rates and the tax implications of accepting such offers.

Why It Works

While undeniably branded content, with Fidelity openly promoting its services, this post surpasses typical Forbes finance articles in terms of insightful financial advice. Readers should, of course, remain cognizant of Fidelity’s agenda. However, this native advertisement delivers genuine value, aligns with the expectations of Forbes’ audience, and adheres to the publication’s editorial and stylistic guidelines. A commendable example indeed.

5. Vanity Fair’s “Hennessy Fuels Our Chase for the Wild Rabbit … But What Does It All Mean?”

Vanity Fair boasts a rich history of publishing effortlessly stylish lifestyle journalism, making it an ideal platform for native advertising.

This particular native ad seamlessly blends video and written content to provide a behind-the-scenes glimpse into a video about Sir Malcolm Campbell, an English race car driver known as “The Fastest Man on Earth.” Campbell etched his name in history by becoming the first to break the 300mph land speed barrier back in 1935. He remains an enduring symbol of ambition—a fitting personality to endorse a premium liquor brand. Hennessy collaborated with the creative agency Droga5 to produce the video, aligning it with their “Never Stop, Never Settle” campaign.

Why It Works

Beyond drawing a subtle yet impactful parallel between Campbell’s adventurous spirit and Hennessy’s “Wild Rabbit” campaign (described as “a metaphor for one’s inner drive to succeed”), the content itself is engaging. The product placement is handled deftly, avoiding any sense of forcefulness or irrelevance. Furthermore, the piece exudes the same level of sophistication as any other Vanity Fair feature, creating a captivating experience for the reader.

The Hall of Shame: Native Advertising Gone Wrong

Now that we’ve witnessed how experts craft sponsored content, let’s turn our attention to some cringeworthy examples of native advertising from the depths of the internet.

The Atlantic’s “David Miscavige Leads Scientology to Milestone Year”

While The Atlantic swiftly removed this ill-conceived native advertising endeavor from its site, it remains preserved online it will live on forever courtesy of the Poynter Institute for Media Studies, serving as a cautionary tale.

Setting aside the substantial financial incentives The Atlantic must have received for publishing this blatant advertorial, it’s baffling why promoting what many perceive as a questionable organization in a respected national publication ever seemed like a sound strategy.

The Atlantic did attempt to mitigate the damage by prominently labeling the content as “Sponsor Content.” However, this did little to quell the backlash. The publication faced widespread ridicule from mainstream media, cementing this as a prime example of native advertising gone wrong.

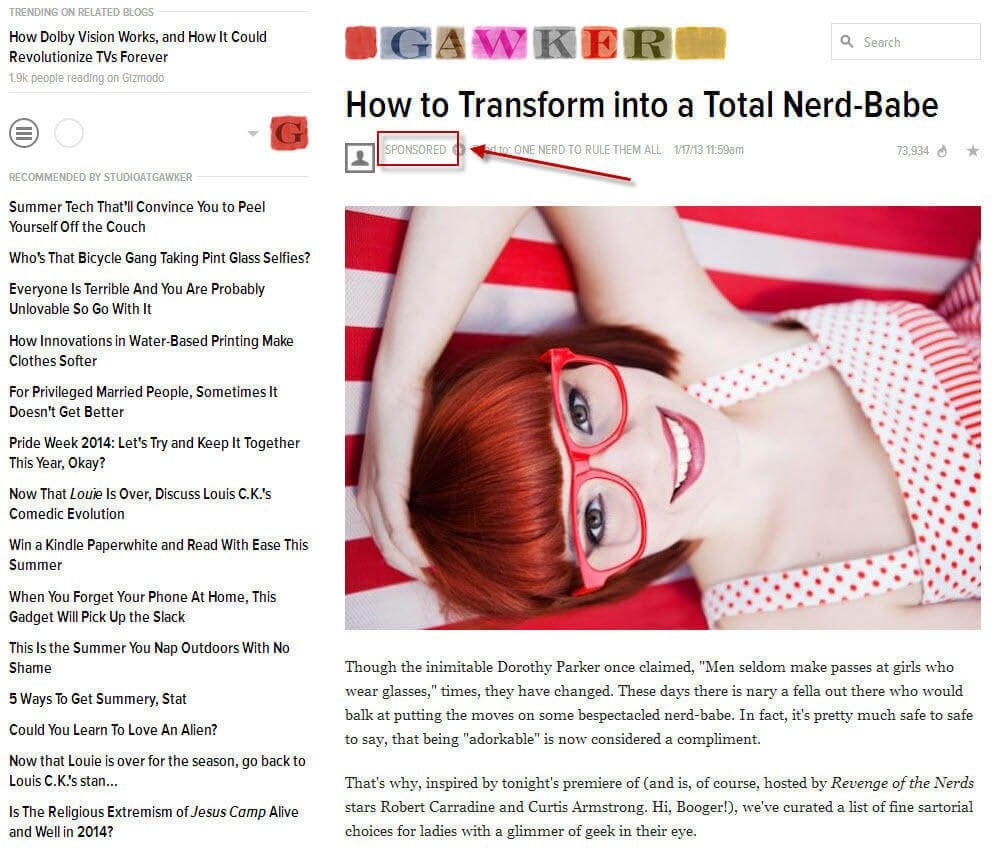

Gawker’s “How to Transform into a Total Nerd Babe”

Every aspect of this “content”—and I use that term loosely—is utterly objectionable and offensive, from its shallow headline to its clichéd copy. And that’s not even the worst part.

This “content” served as an advertisement for the TBS reality show “King of the Nerds.” Aside from the barely noticeable “Sponsored” tag, nothing distinguishes this from Gawker’s usual brand of content. Adding insult to injury, after the promotion ended, the editorial staff didn’t even bother to maintain grammatical correctness, simply deleting the show’s name. Simply shameful.

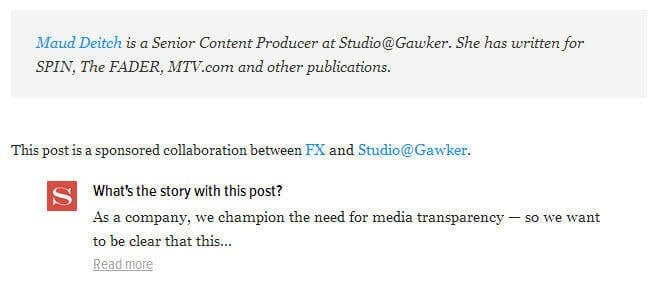

Gawker (rightfully so) faced considerable criticism for this and other native ads, prompting a revised transparency policy. Their native ads now look like this:

Native ads on Gawker are now clearly tagged by network, confined to a dedicated “Studio @ Gawker” section, credited to specific writers, and accompanied by unambiguous disclaimers at the bottom. At the very least, identifying posts to avoid has become easier.

The New York Times’ “Will Millennials Ever Completely Shun the Office?”

This advertorial reaches new levels of awfulness.

Not only is the agenda glaringly obvious from the outset, but the overused “Millennial work ethic” trope is tired and clichéd. Even the article’s premise is ridiculous. Millennials won’t “shun” offices simply because they are burdened by student loans and face employment challenges. The underlying message? If they do choose to work remotely, they can always rely on Dell hardware, right?

The sole redeeming factor of this native ad is its clear distinction from The Times’ actual editorial content. It appears that (as of this writing) the Times has removed Dell’s other sponsored posts, suggesting the experiment was an utter failure.

Oh dear.

Native Ads: More Than Meets the Eye?

Executed effectively, native ads can be engaging, informative, and successful in promoting products or building brands. However, miss the mark, and your readership will hold it against you. Striking the delicate balance between these extremes is challenging, yet it hasn’t deterred publishers from embracing the native advertising trend. Whether the FTC or other regulatory bodies intervene to establish clearer guidelines remains to be seen. For now, both brands and publishers continue to seek the winning formula for native advertising.