This section delves into XML as a data interchange format, contrasting its capabilities with JSON, particularly in managing complex applications. While JSON excels in conciseness for simpler scenarios, its simplicity can become a liability when handling intricate tasks. This necessitates developers to create custom solutions for functionalities not inherent in JSON, potentially leading to inconsistencies and integration issues. For enterprise-level systems demanding robust error handling, these workarounds might introduce vulnerabilities affecting code quality, system stability, and adaptability to future changes. The section then sets the stage to explore whether XML, often perceived as the complex counterpart to JSON, offers solutions to these challenges.

The subsequent part of this article aims to:

- Analyze XML as a data interchange method, assessing its strengths in handling complex requirements.

- Examine the trajectory of JSON and explore solutions that integrate the robust features of XML into JSON, enabling developers to create more reliable and resilient software.

XML often receives the label of being the intricate and verbose sibling of JSON. Even reputable resources like w3schools.com, a widely used reference for web standards, present a rather simplistic comparison favoring JSON in a mere 58 words 1. This oversimplification overlooks the broader capabilities of XML, which extend beyond just data exchange. XML’s design goes beyond mere data interchange; it serves as a language for crafting custom markup languages tailored for diverse applications. Its rigorous syntax enforces data integrity for any XML document or sub-language, establishing a reliable standard. Contrary to the misconception that JSON has completely replaced XML, the latter remains a cornerstone in information representation and exchange globally 2. It continues to be extensively used, defying the notion of its obsolescence.

JSON: Simplicity vs. XML: Power

Part 2 of this article examined data interchange in the context of consumer-driven contracts (CDCs), protocol evolution, and message validation. Using our European Bank case study, we highlighted the challenges of using JSON for secure data exchange with retailers. The bank sought software designs that promoted low coupling, high encapsulation, and adaptability to future changes. However, using JSON for data exchange resulted in the opposite: high coupling, low encapsulation, and reduced adaptability.

Let’s revisit the European Bank scenario but replace JSON with XML as the data interchange format. The XML messages below correspond to the JSON messages for each account identifier type: SWIFT, IBAN, and ACH.

| |

While XML may appear less efficient in terms of raw byte count, its verbosity stems from its comprehensive approach to data exchange. Encoding with JSON addressed the immediate need for data transfer but lacked support for diverse message structures and their validation. To handle consumer-driven contracts, developers would need to introduce custom code, creating tight coupling between the message format, content, and processing logic. Alternatively, a patchwork of libraries and frameworks could be used to address these higher-level needs. Both approaches, however, layer complexity directly onto the data exchange mechanism, resulting in tight coupling with the application. In contrast, XML’s inherent features allow us to address a wider range of requirements without such coupling.

The equivalent XML messages utilize two fundamental aspects of the XML standard: namespaces and instance types. The attribute xmlns="urn:bank:message" defines the message’s namespace, while "xsi:type" specifies its instance type as "swift", "iban", or "ach". These XML standards enable a message processor to not only identify the message type but also reference the schema defining the validation rules.

The XML schema is a key differentiator between JSON and XML. It allows developers to encapsulate the message format’s rules in a separate, application-independent document. This schema can also define value constraints, enabling validation enforced by XML processors. An illustrative XML schema for the European Bank (using namespace: xmlns="urn:bank:message") with type definitions and value constraints is provided below:

| |

This XML schema mirrors the functionality of the isValid(message) function from Part 2. Although the XML schema appears more verbose at first glance, the crucial difference lies in its decoupling from the application, unlike isValid(message). The XML schema is a dedicated language for expressing rules about XML documents, with several variations like DTDs, Relax-NG, Schematron, and W3C XML schema definitions (XSD) 3 commonly used. For the European Bank, the XML schema offers a less risky solution for these higher-level requirements without introducing tight coupling.

Using an XML schema inherently reduces software risk. Validation rules are defined in a dedicated schema language, separate from the application logic. This decoupling ensures that the message format’s interpretation and its processing remain independent. The XML schema provides the European Bank with an encapsulated layer solely responsible for message validation, variability, versioning, and more.

The XML schema effectively represents the normative definition of the consumer-driven contract. This offers a lower-risk approach for the European Bank, pushing the error space $\xi_0$ closer to 0. Both the bank and the retailer can leverage the schema to validate and enforce the contract, thanks to its decoupled nature.

Decoding the Verbosity of the XML Schema

The XML schema specification provides developers with a language to implement structural and logical rules that define and constrain elements within any XML document. This enables embedding deeper meaning into each component of an XML document. For instance, the XML schema allows for:

- Defining regular expression constraints for text strings within the document.

- Defining ranges and specific formats for numeric values.

- Defining whether specific elements and attributes are mandatory or optional.

- Defining relationships between elements within the document using keys and references, among other features.

The XML schema empowers systems to leverage generic XML validators to verify the integrity of incoming messages. This intrinsically minimizes the “error space” $\xi_0$, automatically shielding the core business logic from invalid inputs.

Mitigating the Risks of Future Development

Systems can leverage inherent features of the XML specification to reduce the risk associated with future development. By establishing a common contract through an XML schema, systems define the rules and constraints governing data exchange, encompassing all objects and properties (elements and attributes in XML). This foundation allows them to harness XML’s capabilities for handling message variations, protocol versioning, and content validation. For example, XML namespaces equip messages with the information needed to:

- Determine the specific version of the message being exchanged.

- Locate and reference the agreed-upon contract schema.

- Perform validation to ensure the correctness and integrity of the XML document.

With the wide array of features and capabilities offered by the XML schema, XML itself can address most of the complexities associated with data exchange. This underscores the sentiment behind Dr. Charles Goldfarb’s statement referring to XML as the “holy grail of computing.” 4

The XML schema empowers applications to be resilient to errors and adaptable to future changes.

XML enjoys widespread adoption and has been rigorously tested, with a vast ecosystem of libraries available across various platforms to facilitate the processing and validation of XML documents. Choosing XML as the data interchange format empowers developers to address not only immediate requirements but also those related to consumer-driven contracts, message variability, protocol versioning, and content validation. This allows them to effectively manage the risks associated with complex requirements and, more crucially, adapt to unforeseen future needs.

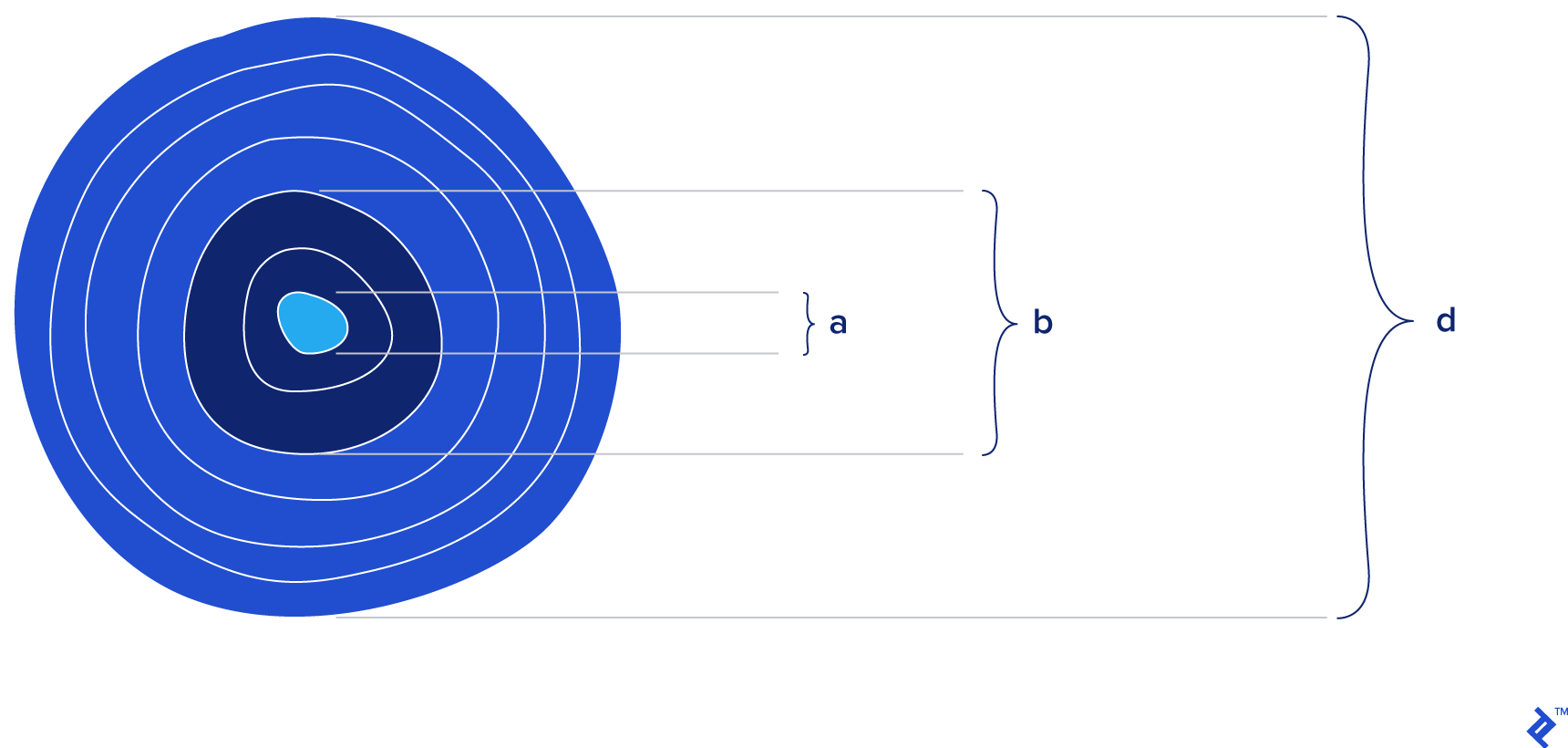

XML’s capabilities extend beyond data exchange, offering solutions for a broader range of challenges compared to JSON. When viewed from this perspective, XML encompasses a larger portion of the application’s architecture, effectively absorbing several layers of complexity within its own scope.

When selecting a data interchange format, should we focus solely on the core data exchange, or consider the broader architectural implications and future needs of the application?

Contrasting JSON and XML: The Fundamental Differences

XML’s capabilities reach far beyond simple data exchange, allowing it to handle complexities that JSON struggles with. It addresses a wider range of complex requirements related to data exchange, allowing systems to utilize standardized, decoupled libraries and frameworks.

As a specification, XML inherently addresses these complex requirements. It’s a well-defined standard established by the W3C and supported by all major software vendors and programming languages. Adopting XML for data interchange inherently leads to a systematic reduction in software risk for applications.

Charting the Future of JSON

There’s no doubt that JSON will remain a significant player in the data interchange landscape. Its close ties to JavaScript, the dominant development platform today, have cemented its place. JSON is a perfect fit for smaller, less complex projects. However, as we strive to build larger, more sophisticated applications, the inherent complexity of our software will inevitably increase. Inspired by XML’s robust features, several groups are developing similar standards for JSON.

A key limitation of JSON lies in its lack of a standard way to formally describe the logical structure and constraints of its data.

JSON Schema: Bridging the Gap

Initiated in 2009, the JSON schema 5 project aims to provide a standardized vocabulary for describing and validating JSON documents. It uses JSON’s syntax to define rules and constraints for the elements within JSON data. Several projects across various platforms have implemented libraries that support the JSON schema specification.

While not yet an official standard, the JSON schema project addresses a range of needs similar to what the XML schema offers. This vocabulary empowers developers to define logical and structural rules and constraints for JSON documents, enabling validation using libraries that are decoupled from the application, thus reducing the need for tightly coupled, custom code. By incorporating the JSON schema, developers can choose JSON as their data format while mitigating risks associated with complex requirements that were previously difficult to address with JSON alone.

The JSON schema project, a community-driven effort, has become the most widely adopted specification for JSON schemas after a decade of revisions. Although not yet an official standard, its widespread adoption underscores the strong demand for such a solution.

Conceptually, the JSON schema shares similarities with the XML schema. However, a closer comparison reveals differences in their models, capabilities, and underlying logic. For example, while the JSON schema language defines numerous properties to constrain JSON values, its extensive set of attributes can lead to contradictory schema definitions.

For instance, the following snippet defines an "object" type with three properties: "number", "street_name", and "street_type".

| |

Introducing an additional constraint like "minProperties": "4" to the "object" type definition creates a logical conflict because only three properties are explicitly defined.

The abundance of constraint properties within the JSON schema, some overlapping in functionality, presents two main challenges:

- The extensive vocabulary and nuanced semantics of the JSON schema can lead to a steeper learning curve for developers.

- The complexity of the specification makes it challenging to create consistent implementations of validation libraries, potentially leading to inconsistencies across different libraries.

While the XML schema language is not entirely immune to contradictory definitions, they are far less frequent and less severe. This is partly because the XML schema specification was developed with a focus on being both developer-friendly and straightforward to implement in validation libraries.

Furthermore, while the JSON schema project defines the schema language, its implementation is left to various community projects.

The JSON schema validator 6 is a widely used project that implements a JSON schema validator for the Java platform. Integrating this library allows Java applications to verify the conformance of all JSON documents they exchange. Similar implementations exist for a variety of other platforms.

Let’s revisit the European Bank example and use the JSON schema to define a schema for JSON messages containing account identifiers.

| |

This JSON schema defines three object types: "swift", "iban", and "ach". Regular expression patterns are used to validate account information, and both "type" and "code" are marked as required properties for all types. Additionally, "routing" is a required property specifically for the "ach" type. By utilizing this JSON schema, the European Bank can validate incoming JSON messages, ensuring data integrity for all interactions.

While the JSON schema introduces many of XML’s capabilities to JSON, it’s still under development. Despite being a valuable tool for managing software risk, the JSON schema specification has room for improvement. Its organic evolution has led to the omission of potentially important features and the inclusion of structural and logical patterns that can be confusing. For instance, the lack of support for defining abstract types might force developers to implement convoluted workarounds, introducing further risks 7.

Despite its limitations, the JSON schema project has made significant contributions to the concept of a schema language for JSON. Its extensive features, though requiring further refinement for clarity and consistency, make it a versatile solution that brings many of XML’s strengths to the JSON ecosystem.

For a more in-depth look at the JSON schema specification, refer to Understanding JSON Schema.

JSONx: Merging the Strengths of JSON and XML

The JSONx project, initiated in 2014, takes a different approach by directly leveraging XML to provide a powerful schema solution for JSON, specifically designed for enterprise use. It introduces the JSON schema definition (JSD) language, closely modeled after the XML schema specification. This allows the JSD to define structural and logical patterns that resemble those found in the XML schema definition language.

Let’s apply the JSD language to the European Bank example to create a schema for JSON messages containing account identifiers.

| |

At first glance, the JSD schema might appear similar to the JSON schema. However, one noticeable difference lies in the more concise and intuitive semantics of the JSD. In this example, the JSD places the "use": "required" property directly within the property definition, while the JSON schema associates it with the parent object, requiring property names to match. The constraint "use": "required" is explicitly stated only for the "code" property of the "swift" object and omitted for others because it’s the default value. The JSD language was designed with such nuances in mind, offering a cleaner and more user-friendly way to express JSON schemas.

A distinguishing feature of the JSONx project is its focus on clarity and practicality for developers. This is evident in the JSD’s ability to be represented in both JSON (JSD) and XML (JSDx) formats, allowing developers to utilize advanced XML editing tools for creating and validating JSD documents, ensuring accuracy and reducing errors.

The JSD schema from above can be expressed in the following JSDx format:

| |

The JSDx format provides a clear, self-validating, and less error-prone way to define JSON schemas.

The JSD language is designed to prevent contradictory definitions and follows standard patterns for expressing constraints. Its close resemblance to the XML schema definition (XSD) language ensures that type declarations and constraint definitions in JSD closely mirror their XML counterparts. The JSD(x) specification provides a comprehensive solution for defining structural and logical rules for JSON documents. Furthermore, it’s self-describing, meaning the JSD(x) language itself is defined using the JSD(x) format. For a deeper dive into the JSD(x) specification, refer to JSON Schema Definition Language.

Beyond the JSD(x) language, the JSONx project provides reference implementations of JSD(x) processors and validators. It also includes a class binding API and code generator for the Java platform. This empowers developers to generate strongly-typed Java classes based on a JSD(x) schema, facilitating the parsing and serialization of JSON documents that adhere to the schema. These generated classes provide a type-safe link between the schema and the Java platform, representing the usage, constraints, and relationships defined in the schema. This strong typing further reduces software risk by catching potential incompatibilities introduced by future modifications at compile time.

By leveraging Java’s compiler, these strongly typed bindings highlight incompatibilities early in the development cycle through compile-time errors. This significantly reduces the risk of data-related bugs in message processing. This approach allows developers to implement changes and address incompatibilities quickly and with confidence, without relying on runtime checks or user feedback to uncover issues. The binding API utilizes Java annotations, enabling a lightweight yet robust way to associate any class with a JSD(x) schema using strong types. The strong typing and code generation capabilities of JSONx fully support the JSD(x) specification, making it well-suited for the rigorous demands of enterprise solutions.

Developed with enterprise solutions in mind, the JSONx framework offers a high standard of quality and utility for complex systems, combined with ease of use and edit-time error validation for developers.

The JSD(x) binding engine, processor, and validator boast an impressive 87% test coverage, giving Java developers confidence in integrating the framework for binding JSD(x) schemas to their applications, allowing them to reliably encode, decode, and validate JSON documents. For a closer look at the JSONx framework for Java, refer to JSONx Framework for Java.

Conclusion

Examining the evolution of the web and software development trends reveals a close correlation between the rise of JavaScript and the popularity of JSON. However, numerous articles and blog posts tend to offer a limited perspective when comparing JSON and XML, often prematurely dismissing XML as obsolete. This leads to many developers being unaware of XML’s powerful capabilities that can enhance software architecture, resilience to change, and overall quality and stability. A deeper understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of both standards empowers developers to make more informed decisions for their projects.

Similar to how the “divergence catastrophe” with HTML led to the creation of XML, a similar phenomenon can be observed in complex codebases heavily reliant on JSON for data exchange. JSON lacks the ability to encapsulate the functionalities surrounding data exchange, leading to logic fragmentation in higher application layers. In contrast, XML allows developers to push this complexity to lower layers, facilitating early bug detection. This is particularly beneficial for compiled languages where, combined with a binding framework, XML-based architectures can significantly minimize the potential for data-related errors. For enterprise-level systems, these powerful capabilities in systematically reducing software risk solidify XML’s position as a valuable tool in software development.

While JSON remains a prominent data interchange format, several projects are actively working to bridge the gap by bringing XML’s robust features to the JSON ecosystem. The JSON schema project offers a community-developed schema specification that has organically grown to support a wide range of attributes and patterns for describing and constraining JSON documents. On the other hand, the JSONx project provides an enterprise-grade schema language closely modeled after the XML schema definition language, offering both JSON and XML formats for defining JSON schemas. These specifications and frameworks empower developers to mitigate software risks associated with higher-level data exchange requirements, such as consumer-driven contracts, protocol versioning, content validation, and more.

The advanced features inherent in XML were specifically designed to manage software risks associated with markup languages. This applies equally to JSON use cases, making a schema language a time-tested and proven approach to systematically address the myriad software risks associated with data exchange.

References

1. JSON vs. XML (w3schools.com, December 2016) 2. The World Wide Success That Is XML (W3C, July 2018) 3. W3C - What Is an XML Schema? (W3C, October, 2009) 4. The Internet: A Historical Encyclopedia. Chronology, Volume 3, p. 130 (ABC-CLIO, 2005) 5. JSON Schema (July 2008) 6. JSON Schema Validator (GitHub) 7. JsonSchema and SubClassing (Horne, March 2016)