In the first installment of this article, we examined the progression from Web 1.0 to 2.0 and how its challenges led to the emergence of XML and JSON. Due to JavaScript’s significant influence on software development over the past decade, JSON has consistently garnered more attention than any other data interchange format. Numerous online articles compare these two standards, often highlighting JSON’s simplicity and criticizing XML’s verbosity. But is JSON truly superior to XML? A thorough examination of data interchange will expose the strengths and weaknesses of both JSON and XML, clarifying their suitability for various applications, from simple projects to intricate enterprise systems.

This second part of the article will delve into the following:

- A comparative analysis of the fundamental differences between JSON and XML, assessing their appropriateness for projects of varying complexity.

- An exploration of how JSON and XML influence software risk in both common applications and enterprise-level systems, and an investigation into potential risk mitigation strategies for each standard.

The software development landscape is vast and diverse, encompassing various platforms, programming languages, business needs, and scales. While “scale” often refers to user interaction, it also describes software attributes that distinguish simplicity from intricacy, such as “scale of development,” “scale of investment,” and “scale of complexity.” While all developers, whether individuals or teams, aim to minimize software risk in their applications, the strictness of adhering to requirements and specifications distinguishes standard applications from those used in enterprise environments. When considering JSON and XML, this difference in rigor highlights the strengths, weaknesses, and fundamental differences between these two data interchange standards.

JSON in Different Software Environments: From Everyday Apps to Large-Scale Enterprise Systems

To assess the suitability of JSON and XML for various applications, let’s define data interchange and use a straightforward example to illustrate the distinctions between the two standards.

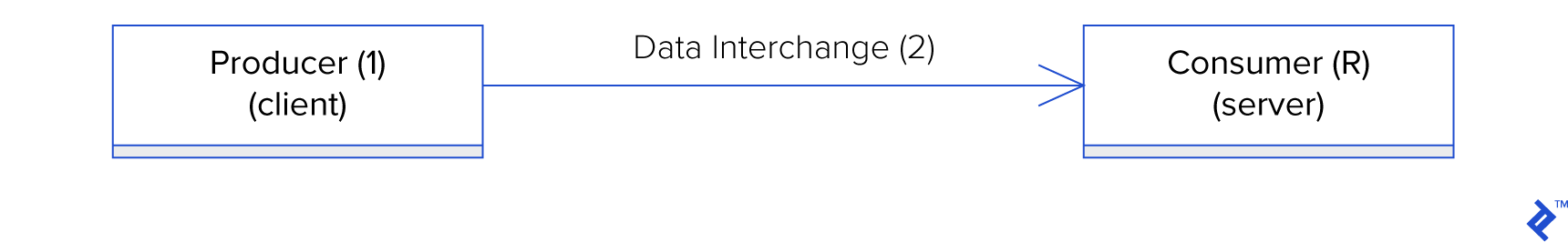

Data interchange involves two endpoints, represented by two actors: a producer and a consumer. The most basic form of data interchange is unidirectional, consisting of three primary phases: data production by the producer (1), data exchange (2), and data consumption by the consumer (3).

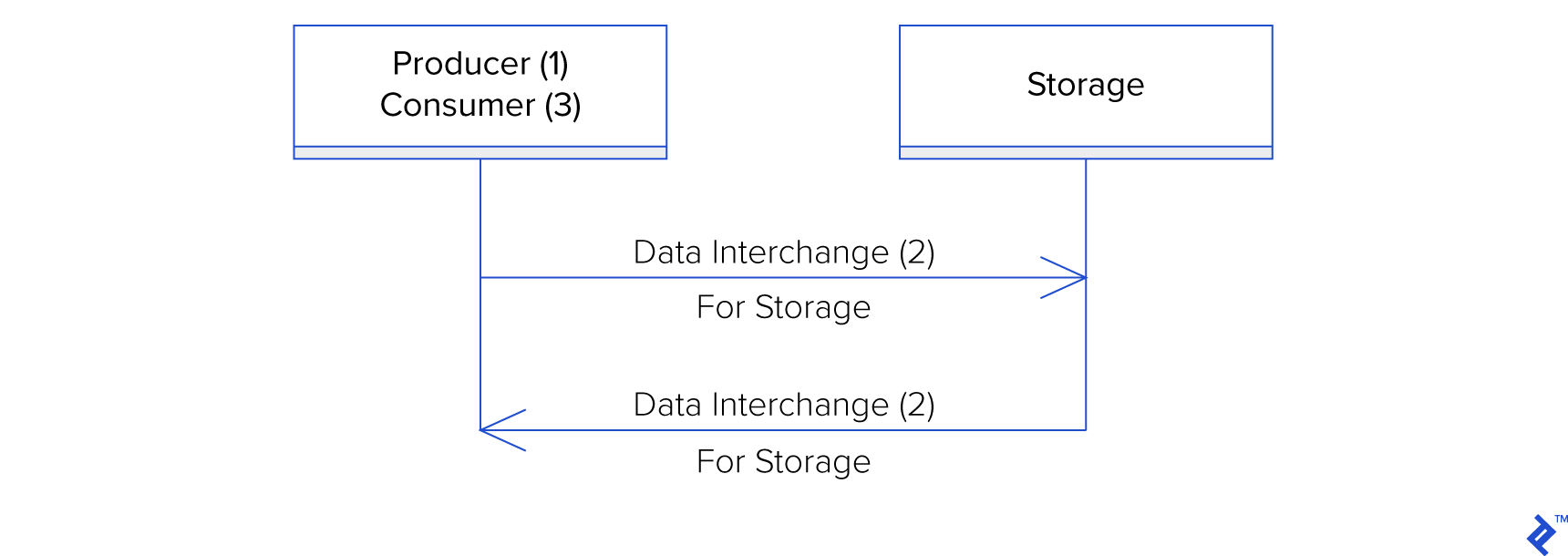

The unidirectional data interchange scenario becomes even simpler if the producer and consumer are the same logical entity, such as when an application uses data interchange for disk storage, acting as the producer at time $\xi_1$ and the consumer at time $\xi_2$.

Regardless of this simplification, the key takeaway is that data interchange provides a standardized format for exchanging data between a producer and a consumer, bridging the gap between data generation (1) and data utilization (3). It’s a fundamentally straightforward concept.

JSON as a Data Interchange Format

JSON’s creator, Douglas Crockford, emphasized that JSON was intentionally designed as a data interchange format.1 From its inception, it was intended to transmit structured data concisely between programs. Crockford outlined JSON in a succinct 9-page RFC document, specifying a format with clear, concise semantics tailored for its intended purpose: data interchange.2

JSON effectively meets the fundamental need to exchange data between two actors efficiently. However, in the real world of software development, these basic requirements are often just the tip of the iceberg. Simple applications with straightforward specifications may only require a simple data interchange mechanism, making JSON a suitable choice. However, as data interchange requirements become more intricate, JSON’s limitations become apparent.

Complex data interchange requirements often stem from the evolving relationship between the producer and consumer. For example, a software system’s evolutionary path may not be fully known during its initial design and implementation. Over time, objects or properties within a message format might need to be added or removed. If numerous parties are involved in producing or consuming the data, the system might also need to accommodate both current and previous versions of the message format. This challenge, known as managing consumer-driven contracts (CDC), often arises when service providers need to evolve the agreement between themselves and their consumers.3

Navigating Consumer-Driven Contracts

Let’s illustrate this with an example of a consumer-driven contract between a European bank and a retailer. The contract dictates how customer bank information is shared during a purchase transaction.

SWIFT is a long-standing standard for the electronic exchange of bank transactions.4 At its core, a SWIFT message includes a SWIFT code to identify an account, along with purchase-specific details.

| |

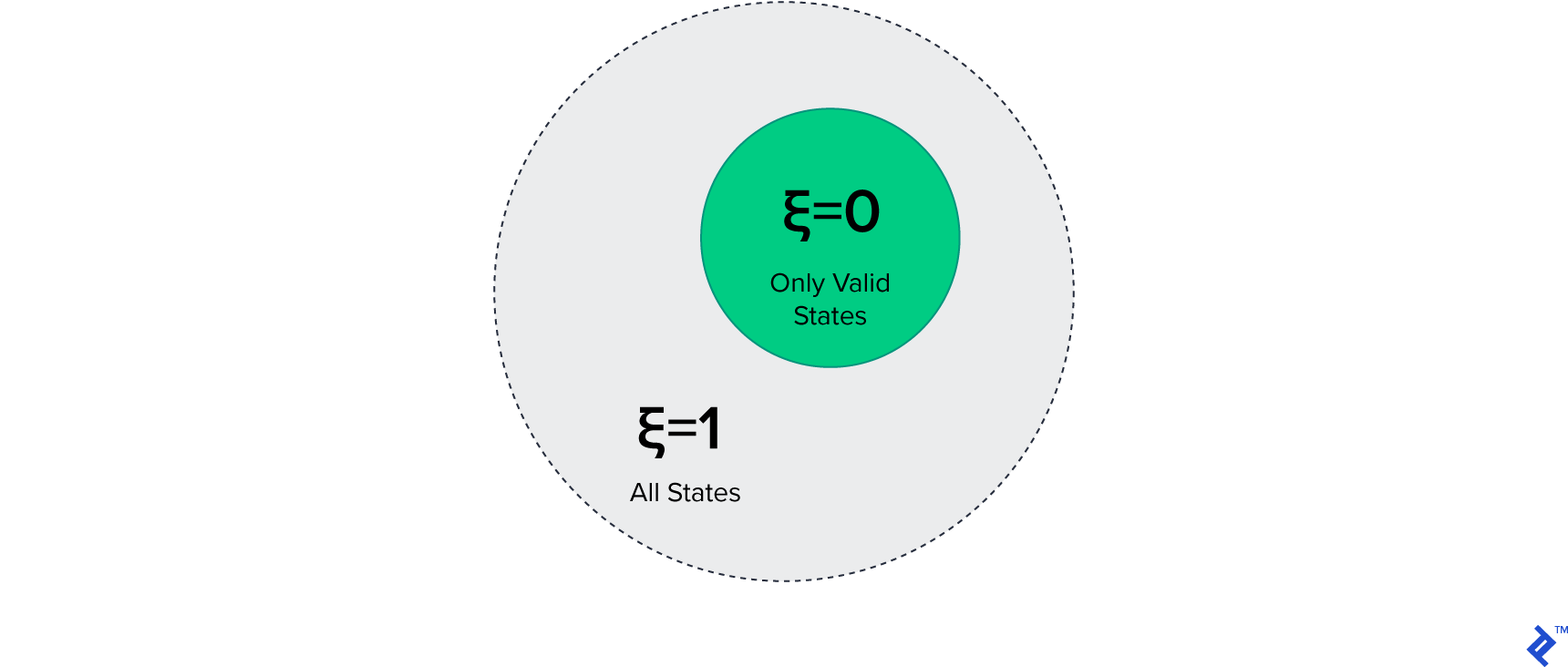

This message, containing the property code, possesses a “state space” determined by the possible values of code. The state space encompasses all expressible states of the message. By distinguishing between valid and invalid states within the state space, we can pinpoint the subset representing errors, referred to as the error space. Let $\xi$ represent the message’s error space, where $\xi = 1$ encompasses all valid and invalid states (the entire state space), and $\xi = 0$ represents only valid states.

The data interchange layer, the consumer’s point of contact, has an error space denoted as $\xi_0$ (the subscript 0 indicates the entry point layer). This value is determined by the ratio of all possible inputs, both valid and invalid, to those considered valid. Input message validity is assessed on two levels: technical and logical. In JSON, technical correctness hinges on the message’s adherence to JSON’s syntactic rules as defined in Crockford’s RFC document.2 Logical correctness, however, involves verifying the validity of account identifiers according to the SWIFT standard, which mandates “a length of 8 or 11 alphanumeric characters and a structure conforming to ISO 9362."5

After years of successful operation, regulatory changes necessitate that the European bank and retailers modify their consumer-driven contract to accommodate a new account identification standard: IBAN. The JSON message is adjusted to include a new property called type to distinguish between SWIFT and IBAN identifiers.

| |

Subsequently, the European bank expands into the US market and establishes a new consumer-driven contract with US retailers. This expansion requires support for the ACH account identification system, prompting further modification of the message to include "type": "ACH".

| |

Each expansion of the JSON message format introduces potential risks to the application. At the time of the initial SWIFT integration, the need to support IBAN and ACH was unknown. With numerous retailers exchanging data with the bank, the potential for errors grows, pushing the bank to implement measures for risk mitigation.

The European bank, as an enterprise-level solution, prioritizes error-free operation with its retail partners. To achieve this, the bank aims to minimize the error space $\xi_0$ from 1 (representing all possible errors) to 0 (representing no errors). Organizations governing the SWIFT, IBAN, and ACH code standards provide simple test functions, expressible as regular expressions, to verify the logical correctness of identifiers.

| |

To approach an error space of 0, the bank’s system needs to rigorously test each input message to identify potential errors. Since JSON’s functionality is limited to data interchange, the logic for validation has to be implemented within the system itself. An example of such logic is:

| |

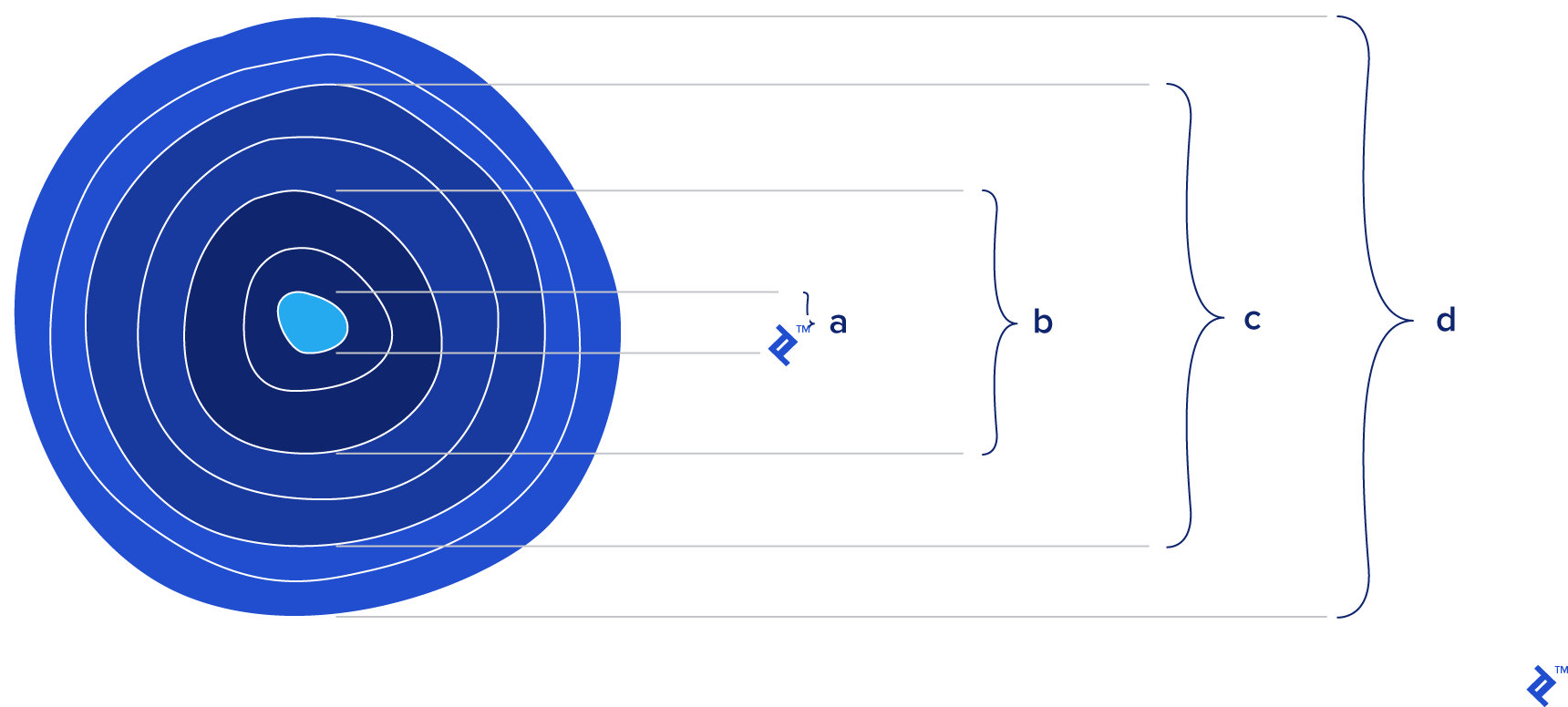

The complexity of the validation logic directly correlates with the complexity of the message variants requiring validation. The European bank’s simplified message format allows for relatively straightforward validation logic. However, for messages with numerous properties, particularly those with nested objects, the validation process can become significantly more complex, both in terms of code length and logical intricacy. With JSON as the data interchange format, the validation layer is tightly integrated into the system. Because the validation layer processes input messages, it inherits the error space ($\xi_0$) of the data interchange layer.

Each layer within a software system possesses its own error space, denoted as $\xi$. The validation layer positioned above the data interchange layer has its own potential for errors, represented by $\xi_1$, which is influenced by the complexity of its own code. For the European bank, this complexity lies in the isValid(message) function. Since the validation layer relies on input from the data interchange layer, its error space ($\xi_1$) is affected by $\xi_0$. This relationship highlights a pattern: the error space of a given layer is influenced by the error space of the layer below it, which in turn is affected by the layer below it, and so on. This relationship can be represented as follows:

$\xi_n = \alpha_n \times \xi_{n - 1}$

In this equation, $\xi_n$ symbolizes the error space of layer $n$. It’s calculated as a function of $\xi_{n - 1}$ (the error space of the preceding layer) multiplied by $\alpha_n$, representing the error potential introduced by the code complexity within layer $n$ itself. This illustrates how errors can compound based on the complexity of each layer.

A resilient system is one that minimizes its software risk by reducing the complexity of its inputs, internal processing logic, and outputs.

The Relationship Between Complex Requirements and Software Risk

The “software risk” of a system is essentially equivalent to $\xi_N$, where $N$ represents the uppermost layer in the system. Assessing $\xi_N$ during the architectural design phase of a new application can be challenging due to the limited visibility of the final implementation. However, a system’s overall complexity, and thus its inherent risk, can be estimated by analyzing the complexity of its requirements.

Software risk is directly proportional to the complexity of the requirements. As requirements become more intricate, the potential for bugs and errors increases. More complex message formats necessitate more error-handling considerations within the system. This is particularly crucial for service providers dealing with diverse systems, as they need to adopt a defensive approach to message handling.

For applications with complex requirements, particularly enterprise-level systems, mitigating software risk is paramount.

To manage the risk associated with logical complexity, the programming principle of “encapsulation” helps developers structure code into layers with clear boundaries. Each encapsulated layer validates its inputs, processes them, and passes the results to the next layer. This methodical approach aims to systematically reduce the “error space” ($\xi$) at each layer ($n$). Effective encapsulation leads to higher cohesion, meaning that each module has a well-defined responsibility and avoids unnecessary dependencies.

JSON as a Data Interchange Format for Complex Requirements

When using JSON as the data interchange format in systems with complex requirements, the complexities surrounding the data interchange often bleed into other layers of the application. JSON’s simplicity, while advantageous in straightforward scenarios, can become a liability as the need for complex data validation and processing arises. To manage this risk, developers often rely on encapsulation to separate message validation from the core business logic.

However, JSON’s tight integration with JavaScript can lead to validation logic being intertwined with the business logic, often residing in higher layers of the application stack. While an intermediary layer dedicated to handling message variant translations would be a more robust solution, this approach is often deemed excessive and is therefore rarely implemented.

For example, the logic to validate an account identifier can be implemented in one of two ways:

- Within a dedicated validation layer positioned just above the data interchange layer: This approach promotes encapsulation, clear responsibility assignment, and logical cohesion.

- Embedded directly within the business logic: This approach leads to a merging of responsibilities and tight coupling, making the system harder to maintain and more prone to errors.

When JSON is used for data interchange in complex systems, the validation logic becomes intertwined with the application code. Implementing the isValid(message) function within the application creates a tight coupling between the logical interpretation of the message format (which is negotiated between the producer and consumer as part of the consumer-driven contract) and the technical implementation of message processing. Consequently, the scope of the consumer-driven contract broadens to include validation and the processing code handling different message variants.

From this perspective, JSON can be seen as the core of an onion, surrounded by layers representing additional logic required for validation, processing, business logic, and so on.

When selecting a data interchange format for an application, the decision should consider not just the core data representation, but also the complexities and potential overhead it might introduce in other parts of the system.

Custom validation logic implemented on the consumer side is not inherently reusable by the producer or vice versa. This is especially true when systems are built on different platforms, making it impractical to share validation functions between parties involved in a communication protocol. Code sharing is only feasible if both systems use the same platform and the validation function is properly encapsulated and decoupled from the application logic. However, this ideal scenario is often unrealistic. As validation logic becomes more complex, integrating it directly within the application can lead to unintended (or sometimes intended) coupling, rendering the function difficult to share.

For instance, the European bank might want to further mitigate risk by requiring retailers to perform message validation on their end as well. This would necessitate that both the bank and the retailers implement their own versions of the isValid(message) function. However, with each party responsible for their own implementation, this approach introduces several challenges:

- Potential discrepancies: There’s a risk of inconsistencies between the implementations developed by different parties.

- Tight coupling: The logical meaning of the message format becomes tightly coupled to the technical implementation of its processing in each system.

The dotted line represents the lack of a standardized way to formally express a consumer-driven contract that would bind both the producer and consumer. Enforcing the contract becomes the responsibility of each party through their own implementations.

Bridging the Gap with Open-Source Libraries

While JSON excels as a simple and efficient data interchange standard, it lacks built-in mechanisms to assist developers with managing the complexities that extend beyond basic data representation. To address these complexities, developers often resort to one of two architectural approaches:

- Custom code implementation: This approach, as exemplified by the

isValid(message)function, risks tight coupling and reduced code maintainability. - Integration of third-party libraries: While this approach leverages existing solutions, it introduces the software risk associated with relying on external dependencies.

Numerous open-source solutions aim to address common challenges surrounding data interchange. However, these solutions are often specialized, targeting specific aspects of the problem without offering a comprehensive solution. For instance:

- OpenAPI: An open-source specification defining an interface description format for REST APIs.6 While OpenAPI facilitates REST service discovery and specification, it doesn’t inherently address the enforcement of consumer-driven contracts.

- GraphQL: A popular library developed by Facebook to simplify data querying.7 GraphQL enables consumers to access data from producers by exposing APIs directly at the data layer. While this approach can reduce boilerplate code in simple applications, it can lead to reduced encapsulation, lower cohesion, and tighter coupling in enterprise systems, potentially increasing software risk.

Relying on JSON for data interchange often leaves companies and developers to assemble a patchwork of libraries and frameworks to meet complex requirements. This lack of standardization makes it challenging to find solutions that simultaneously address these needs:

- Effectively handling the complexities surrounding data interchange to fulfill system requirements and specifications.

- Maintaining high encapsulation and cohesion while minimizing coupling to reduce overall software risk ($\xi_N$).

Due to the non-standard nature of these solutions, projects inherit the risks associated with each dependency. Applications heavily reliant on external libraries generally carry a higher software risk compared to those with fewer dependencies. To manage risk in complex applications, developers and software architects often prioritize established standards over custom solutions. Standards offer a higher degree of stability and assurance that they won’t suddenly change, break, or become obsolete, unlike custom solutions, especially those integrating a mix of open-source projects with their own evolving risks.

Assessing JSON: Strengths and Weaknesses

Among data interchange standards, JSON stands out for its simplicity, compactness, and human-readable format. For simple applications with straightforward requirements, JSON’s basic data interchange capabilities suffice. However, as the demands on data interchange escalate, JSON’s limitations become increasingly apparent.

Similar to how HTML’s limitations led to the creation of XML to address the “divergence catastrophe,” complex codebases relying on JSON for data interchange can experience a comparable effect. JSON lacks standardized mechanisms to handle common data interchange functionalities, leading to fragmented logic spread across different application layers. Essentially, JSON’s simplicity pushes the responsibility of managing data interchange complexities onto other parts of the application, potentially jeopardizing code quality and maintainability.

The core limitation of JSON lies in its lack of a standardized way to formally describe the logical structure and constraints of its documents.

For enterprise applications requiring robust error handling, relying solely on JSON for data interchange can inadvertently increase software risk and create obstacles to achieving high code quality, stability, and adaptability to future changes.

JSON’s straightforward syntax and inherent simplicity are advantageous for basic data exchange. However, without proper architectural consideration, its use in complex systems can erode encapsulation and introduce unforeseen challenges. While JSON handles basic data representation effectively, managing complexities such as consumer-driven contracts, protocol versioning, and content validation requires additional mechanisms external to JSON itself.

Developers can mitigate these challenges through meticulous encapsulation, creating well-defined layers to handle these additional requirements in a cohesive and decoupled manner. However, this necessitates significant architectural effort early in the development process. To avoid this overhead, developers often opt for solutions that blur the lines between layers, spreading data interchange complexities throughout the application and potentially increasing the risk of errors.

In essence, while JSON is a convenient and efficient choice for simple applications, its use in systems with complex data interchange needs warrants careful consideration. Its apparent simplicity can mask potential risks, particularly for enterprise systems that prioritize code quality, stability, and resilience.

In the upcoming Part 3 of this article, we will shift our focus to XML as a data interchange format, comparing and contrasting its strengths and weaknesses with JSON. Armed with a deeper understanding of XML’s capabilities, we will explore the future of data interchange and examine current initiatives that aim to bring the robustness of XML to JSON.

References

1. Douglas Crockford: The JSON Saga (Yahoo!, July 2009) 2. RFC 4627 (Crockford, July 2006) 3. Consumer-Driven Contracts: A Service Evolution Pattern (MartinFowler.com, June 2006) 4. Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (Wikipedia) 5. ISO 9362 (Wikipedia) 6. OpenAPI - Swagger 7. GraphQL - A query language for your API