A lot of current C projects have their roots in the past, sometimes going back decades.

Take the UNIX operating system, for instance. Work began on UNIX in 1969, and its code was rewritten in C in 1972. The motivation behind creating the C language was to transition the UNIX kernel code from assembly language to a higher-level language, which would do the same tasks with fewer lines of code.

Similarly, Oracle database development commenced in 1977, with its code being rewritten from assembly to C in 1983, contributing to its global popularity.

Windows 1.0 was launched in 1985. While the source code for Windows isn’t publicly accessible, it’s been confirmed that its kernel is mostly written in C, along with some assembly components.

The Linux kernel, initiated in 1991, is also predominantly written in C. The following year, it was released under the GNU license, becoming a cornerstone of the GNU Operating System. Since the GNU operating system itself was launched using C and Lisp, a significant portion of its elements are written in C.

However, C programming isn’t confined to legacy projects that predate the current abundance of programming languages. Numerous C projects are still launched today for good reason.

How C Powers the World

Despite the prevalence of higher-level languages, C continues to be a driving force. Let’s explore some systems used by millions that rely on C programming.

Microsoft Windows

The core of Microsoft Windows, its kernel, is developed mostly in C, with some portions in assembly. For many years, the world’s most widely used operating system, boasting about 90 percent of the market share, has relied on a kernel written in C.

Linux

Similarly, Linux is largely written in C, with some assembly language components. A staggering 97 percent of the world’s 500 most potent supercomputers run the Linux kernel, and it’s also widely used in personal computers.

Mac

Mac computers also draw their power from C, given that the OS X kernel is written mostly in C. As with Windows and Linux, every program and driver on a Mac operates on a kernel built with C.

Mobile

iOS, Android, and Windows Phone kernels are all written in C. These are essentially mobile adaptations of existing Mac OS, Linux, and Windows kernels. Consequently, the smartphones we use daily rely on C-powered kernels.

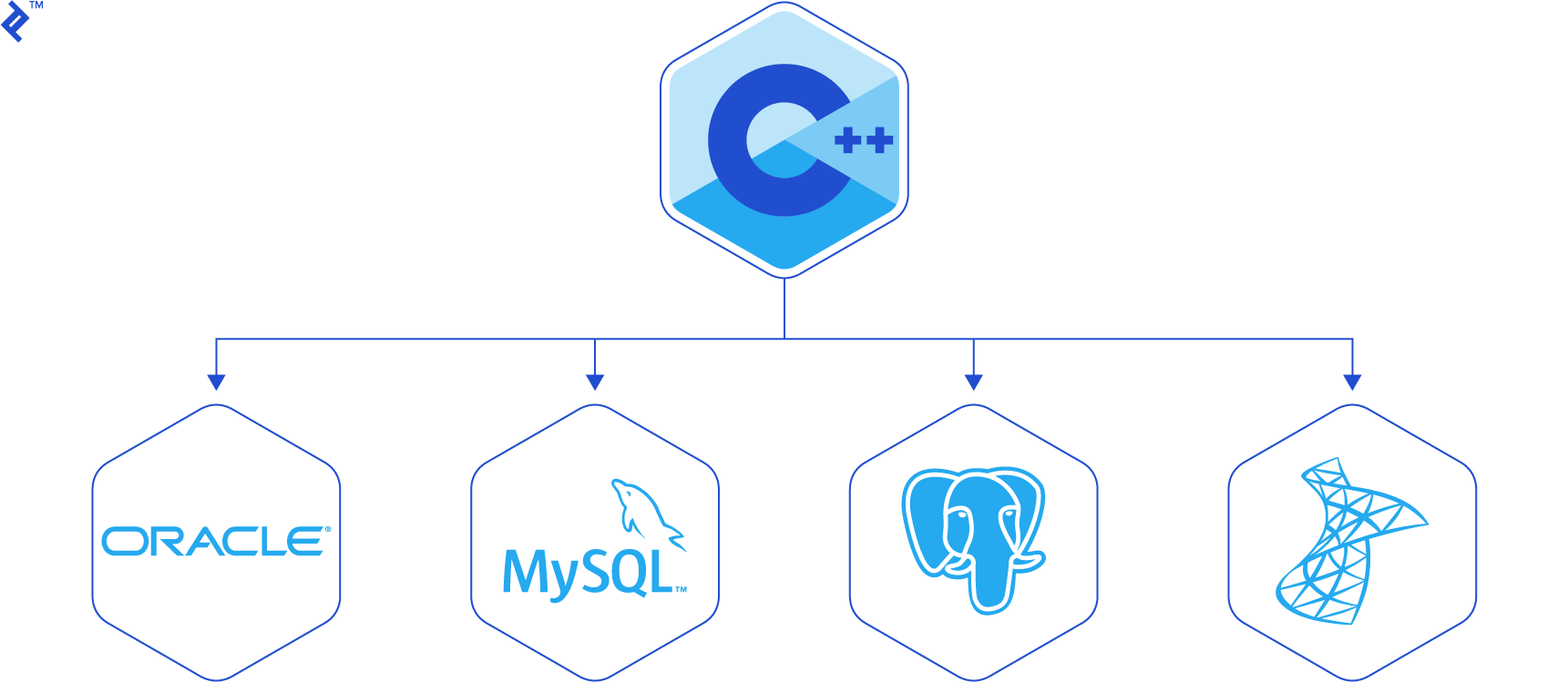

Databases

Leading databases globally, such as Oracle Database, MySQL, MS SQL Server, and PostgreSQL, are coded in C (with the first three employing both C and C++).

Databases are integral to a wide array of systems, spanning finance, government, media, entertainment, telecommunications, healthcare, education, retail, social networks, the web, and more.

3D Movies

The applications used to create 3D movies are commonly written in C and C++. These applications demand exceptional efficiency and speed due to the massive datasets and calculations they handle every second. Enhanced efficiency translates to shorter production times for artists and animators, ultimately saving companies money.

Embedded Systems

Consider your typical day. Your alarm clock is likely programmed in C. The microwave or coffee maker you use for breakfast? Also likely C-powered embedded systems. Your TV and radio? More embedded systems, powered by C. Using your garage door remote? You guessed it - likely another embedded system that is most likely programmed in C.

Your car, too, is laden with features potentially programmed in C, including automatic transmission, tire pressure monitoring systems, various sensors, seat and mirror memory, dashboard displays, anti-lock brakes, stability control, cruise control, climate control, child safety locks, keyless entry, heated seats, and airbag control.

At the store, the vending machine dispensing your soda and the cash register processing your purchase are likely running on C. Paying with a credit card? The reader is probably C-powered as well.

These devices are all embedded systems, essentially small computers with microcontrollers/microprocessors running programs, often called firmware. These programs must detect user input and respond accordingly while displaying information. For example, an alarm clock needs to register button presses, duration of presses, and program itself based on this input, all while displaying relevant information to the user.

Take a car’s anti-lock brake system. It must detect sudden tire locking and momentarily release brake pressure to prevent skidding. These calculations are performed by a programmed embedded system.

While programming languages used in embedded systems can vary, C is a dominant choice due to its flexibility, efficiency, performance, and ability to interact closely with hardware.

Why C Still Matters

Despite the emergence of numerous programming languages that offer greater productivity than C for specific tasks, there are compelling reasons why C programming is here to stay.

In the realm of programming languages, one size doesn’t fit all. Let’s delve into the reasons why C is both unparalleled and practically indispensable for certain applications.

Portability and Efficiency

Think of C as “portable assembly.” It gets as close to the machine as possible while maintaining near-universal availability for current processor architectures. You’ll find at least one C compiler for almost any architecture out there. What’s more, the highly optimized binaries generated by today’s compilers make it challenging to outperform their output with hand-written assembly.

C’s portability and efficiency are so impressive that “compilers, libraries, and interpreters of other programming languages are often implemented in C”. Even interpreted languages like Python, Ruby, and PHP rely on C for their primary implementations. C acts as a bridge between compilers for other languages and the machine, serving as an intermediary. Eiffel and Forth, for example, use C as their intermediate language. Instead of generating machine code for each supported architecture, compilers for these languages produce intermediate C code, leaving the machine code generation to the C compiler.

C has also evolved into a common language for developers to communicate with each other. As Alex Allain, Dropbox Engineering Manager and the mind behind Cprogramming.com, puts it:

“C is excellent for expressing fundamental programming concepts in a way that most people grasp. Many principles used in C, like ‘argc’ and ‘argv’ for command-line parameters, loop structures, and variable types, are found in numerous other languages. This common ground allows you to communicate effectively with other programmers, even if they aren’t familiar with C.”

Memory Manipulation

C’s ability to access memory addresses directly and perform pointer arithmetic is crucial for system programming, which includes operating systems and embedded systems.

At the junction of hardware and software, computer systems and microcontrollers assign memory addresses to peripherals and I/O pins. System applications must be able to read from and write to these specific memory locations to communicate with the outside world. That’s where C’s memory manipulation prowess becomes indispensable.

For example, a microcontroller might be designed so that writing a byte to memory address 0x40008000 causes the universal asynchronous receiver/transmitter (UART), a common hardware component for peripheral communication, to send that byte whenever bit 4 of address 0x40008001 is set to 1. The microcontroller automatically resets this bit after it’s set.

Here’s a C function that would send a byte through this UART:

| |

The first line of this function would translate to:

| |

This line instructs the compiler to treat the value ‘0x40008000’ as a pointer to a ‘char,’ then dereference this pointer (access the value it points to) using the leftmost ‘*’ operator, and finally assign the ‘byte’ value to that dereferenced location. In essence, it writes the value stored in the ‘byte’ variable to memory address ‘0x40008000’.

The subsequent line translates to:

| |

Here, a bitwise OR operation is performed on the value at address ‘0x40008001’ and the value ‘0x08’ (binary ‘00001000’, representing a 1 in bit position 4). The result is then stored back to address ‘0x40008001’. In other words, we set bit 4 of the byte residing at memory address ‘0x40008001’. The ‘volatile’ keyword is used to indicate that this value might be modified by processes outside of our code, preventing the compiler from making assumptions about the value at that address after it’s written to. This is crucial information for the compiler’s optimizer. Without the ‘volatile’ keyword, if this operation were within a ‘for’ loop, the compiler might assume the value never changes after the initial setting and skip subsequent executions of the command.

Deterministic Resource Use

System programming often cannot rely on garbage collection, a common feature in many languages. Some embedded systems might not even have the luxury of dynamic allocation. Embedded applications operate with limited time and memory resources and are frequently employed in real-time systems. In these scenarios, an unpredictable garbage collection cycle simply isn’t feasible. If dynamic allocation is off the table due to memory constraints, having alternative memory management mechanisms becomes vital. C pointers offer this flexibility by enabling data placement at specific addresses. Languages heavily reliant on dynamic allocation and garbage collection would be ill-suited for such resource-constrained environments.

Code Size

C has a very small runtime and generates more compact code than most other languages.

Compared to C++, for instance, a C-generated binary deployed to an embedded device can be about half the size of a binary produced from comparable C++ code. A major contributing factor to this difference is exception handling.

Exceptions are a valuable addition in C++ that C lacks. When not triggered and implemented thoughtfully, they incur practically no runtime overhead, but they do increase code size.

Let’s illustrate with a C++ example:

| |

Assume the methods of classes ‘A’, ‘B’, and ‘C’ are defined elsewhere (potentially in different files). The compiler, unable to analyze these methods, cannot determine if they might throw exceptions. Consequently, it must be prepared to handle exceptions potentially thrown by constructors, destructors, or other method calls within those classes. While destructors ideally shouldn’t throw exceptions (doing so is generally bad practice), the possibility remains, whether directly by the user or indirectly through function or method calls.

If any call within ‘myFunction’ throws an exception, the stack unwinding mechanism must be equipped to call the destructors of all successfully constructed objects. One way to implement stack unwinding is to use the return address associated with the last call from this function. This information helps identify the “checkpoint” at which the exception occurred. This is achieved through an automatically generated auxiliary function, akin to a lookup table, which comes into play during stack unwinding if an exception is thrown from within the function. Here’s a simplified representation:

| |

If the exception arises from checkpoints 1 or 9, no object destruction is needed. For checkpoint 3, objects ‘b’ and ‘a’ need to be destructed. For checkpoint 6, it’s ‘c’ and ‘a’. In all cases, the destruction order must be maintained. For checkpoints 2, 4, 5, 7, and 8, only object ‘a’ requires destruction.

This auxiliary function adds to the code size, contributing to the overhead C++ carries compared to C. Many embedded applications cannot accommodate this extra baggage. That’s why C++ compilers for embedded systems often include flags to disable exceptions. However, disabling exceptions in C++ isn’t without its drawbacks. The Standard Template Library (STL) relies heavily on exceptions for error reporting. Working without exceptions necessitates more effort from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standard_Template_Library to identify potential issues and debug their code.

Keep in mind that we’re talking about C++, a language that embodies the principle of “You don’t pay for what you don’t use.” This increase in binary size is exacerbated in other languages that introduce additional overhead with features that, while beneficial, are untenable for embedded systems. While C might not provide these extra features, it shines in scenarios where a compact code footprint is paramount.

Why Learn C?

C is very approachable, and the rewards of learning it are well worth the effort. Let’s explore some of the advantages.

A Common Tongue

As we’ve touched upon, C serves as a common language among developers. It’s not unusual to find implementations of new algorithms, whether in textbooks or online resources, initially or exclusively available in C. This approach maximizes the portability of the implementation. I’ve encountered programmers online struggling to translate a C algorithm into another language simply because they lacked a basic understanding of C.

Given C’s longevity and widespread use, you’re bound to stumble upon algorithms written in it across the web. Knowing C is likely to prove beneficial throughout your programming journey.

Understanding the Machine (Thinking in C)

When discussing code behavior or features of other languages with fellow programmers, we often find ourselves “talking in C.” Is a particular piece of code passing a “pointer” to an object, or is it copying the entire object? Could there be any implicit “casting” happening? These are common lines of inquiry.

We rarely delve into the assembly instructions executed by high-level code when analyzing its behavior. Instead, we tend to reason in terms of C, providing a clearer mental model of what the machine is doing.

If you can’t pause and think this way about your code, you risk approaching programming with a touch of superstition, blindly trusting that things work without truly comprehending how.

Working on Captivating C Projects

C is the language behind many fascinating projects, from large-scale database servers and operating system kernels to small, self-contained applications that you can tinker with at home for personal fulfillment. Don’t let the lack of familiarity with this venerable language hold you back from pursuing projects that ignite your passion.

Conclusion

C doesn’t appear to be going away anytime soon. Its proximity to hardware, excellent portability, and deterministic resource management make it an ideal choice for low-level development tasks such as building operating system kernels and embedded software. Furthermore, its versatility, efficiency, and solid performance make it a strong contender for applications that involve complex data manipulation, such as databases and 3D animation. While newer languages might surpass C in specific domains, they don’t outshine it in every arena. C remains unmatched when performance reigns supreme.

The world hums along on devices powered by C, devices we use daily, often without realizing it. C represents the past, the present, and, as far as we can tell, the future for many areas within the realm of software.