The contemporary digital landscape is heavily reliant on JavaScript. In recent years, JavaScript has become ubiquitous on the web, revolutionizing the industry. The introduction of Node.js empowered the JavaScript community to leverage the language’s simplicity and dynamic nature to manage everything from server-side to client-side operations, even making strides in machine learning. However, JavaScript has undergone significant transformations in recent years, introducing new concepts such as arrow functions and promises.

Initially, the concepts of promises and callbacks were perplexing during my early encounters with Node.js. Accustomed to procedural code execution, I eventually grasped their significance.

This leads to a crucial question: why were callbacks and promises introduced? Why not simply adhere to sequentially executed code in JavaScript?

Technically, sequential execution is possible. But is it advisable?

This article provides a concise overview of JavaScript and its runtime, challenging the prevailing notion within the JavaScript community that synchronous code is inherently inferior in performance and should be avoided. Is this belief truly accurate?

Before proceeding, this article assumes familiarity with JavaScript promises. For those unfamiliar or seeking a refresher, refer to JavaScript Promises: A Tutorial with Examples.

N.B. This article is based on tests conducted in a Node.js environment, not a pure JavaScript one. Node.js version 10.14.2 was utilized, and benchmarks and syntax heavily rely on Node.js. Tests were performed on a MacBook Pro 2018 with an Intel i5 8th Generation Quad-Core Processor operating at a base clock speed of 2.3 GHz.

The Event Loop

A challenge in JavaScript programming stems from the language’s single-threaded nature. Unlike languages like Go or Ruby, which can spawn threads for simultaneous procedure execution, JavaScript can only execute one procedure at a time.

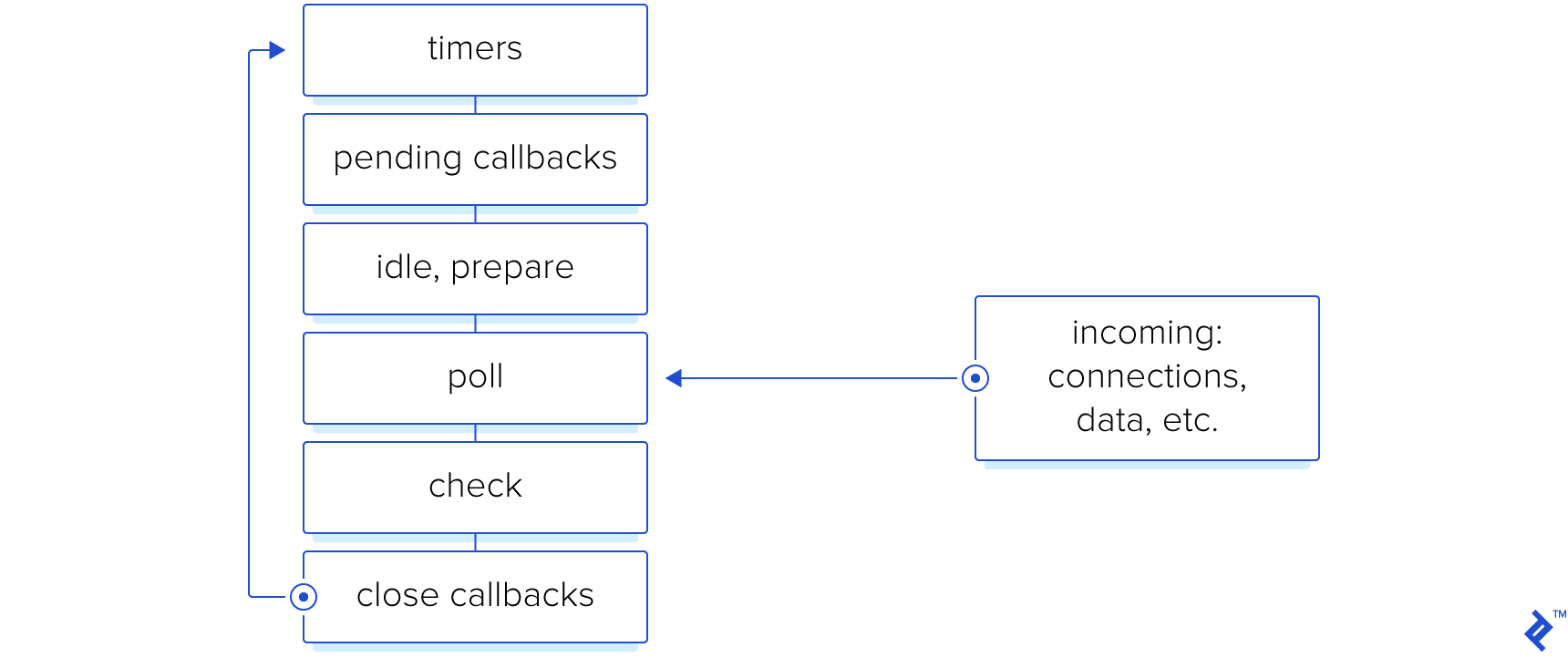

JavaScript utilizes an event loop, a procedure with multiple stages, to execute code. The JavaScript process iterates through these stages repeatedly. Detailed information can be found in the official Node.js guide.

However, JavaScript employs I/O callbacks to overcome the blocking problem.

The need for threads often arises from requests for actions outside the language’s purview, such as fetching data from a database. In multithreaded languages, the requesting thread waits for the database response, which can waste resources. Developers also face the challenge of determining the appropriate thread pool size to prevent memory leaks and resource overallocation under high demand.

JavaScript excels in handling I/O operations. It allows for asynchronous operations like data requests, file manipulations, and shell command execution. Callbacks are executed upon operation completion, or promises are resolved with results or rejected with errors.

The JavaScript community strongly advises against synchronous code for I/O operations to avoid blocking other tasks. Due to its single-threaded nature, synchronous operations like file reading can halt the entire process until completion. Asynchronous code, on the other hand, allows for multiple simultaneous operations with individual response handling, eliminating blocking.

However, in environments where handling numerous processes is inconsequential, wouldn’t synchronous and asynchronous code perform similarly?

Benchmark

Our test aims to benchmark the performance difference between synchronous and asynchronous code, specifically focusing on file reading as the I/O operation.

Initially, a function was written to generate a file with random bytes using the Node.js Crypto module.

| |

This file served as a constant for the next step, which involved reading the file. The code used is as follows:

| |

Executing this code yielded the following results:

| Run # | Sync | Async | Async/Sync Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.278ms | 3.829ms | 13.773 |

| 2 | 0.335ms | 3.801ms | 11.346 |

| 3 | 0.403ms | 4.498ms | 11.161 |

Contrary to the expectation of equal execution times, the results were unexpected. To further investigate, another file was added to the reading process.

The file “test.txt” was duplicated and named “test2.txt.” The updated code is as follows:

| |

An additional read operation was added for each file, and in the case of promises, the reading promises were awaited in parallel. The results were as follows:

| Run # | Sync | Async | Async/Sync Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.659ms | 6.895ms | 4.156 |

| 2 | 0.323ms | 4.048ms | 12.533 |

| 3 | 0.324ms | 4.017ms | 12.398 |

| 4 | 0.333ms | 4.271ms | 12.826 |

The initial run exhibited significantly different values compared to the subsequent three runs. This discrepancy is likely attributed to the JavaScript JIT compiler, which optimizes code with each execution.

The results thus far do not favor asynchronous functions. Perhaps increasing the dynamism and load on the application could yield different results.

Therefore, the next test involves writing and reading 100 different files.

The code was modified to write 100 files before the test execution. Each run generated different files of similar sizes, and old files were cleared before each run.

The updated code is as follows:

| |

The cleanup and execution code is as follows:

| |

Running the test produced the following results:

| Run # | Sync | Async | Async/Sync Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.999ms | 12.890ms | 2.579 |

| 2 | 5.077ms | 16.267ms | 3.204 |

| 3 | 5.241ms | 14.571ms | 2.780 |

| 4 | 5.086ms | 16.334ms | 3.213 |

These findings suggest that as demand and concurrency increase, the overhead associated with promises becomes more pronounced. In scenarios like web servers handling numerous requests per second, the performance benefit of synchronous I/O operations diminishes rapidly.

To further explore the cause of the delay, a function was written to measure the resolution time of an empty promise and 100 empty promises.

The code is as follows:

| |

| Run # | Single Promise | 100 Promises |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.651ms | 3.293ms |

| 2 | 0.758ms | 2.575ms |

| 3 | 0.814ms | 3.127ms |

| 4 | 0.788ms | 2.623ms |

Interestingly, promises do not appear to be the primary source of delay. The delay likely stems from the kernel threads performing the actual reading, although further experimentation is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

A Final Word

So, should promises be used or not?

For scripts running on a single machine with a specific flow triggered by a pipeline or single user, synchronous code is suitable. However, for web servers handling high traffic and numerous requests, the overhead of asynchronous execution outweighs the performance benefits of synchronous code.

The code for all functions used in this article can be found in the repository.

The next logical step in your JavaScript development journey is understanding the async/await syntax. To delve deeper into this topic and its evolution, refer to Asynchronous JavaScript: From Callback Hell to Async and Await.