JavaScript has a unique identity as a programming language. Drawing inspiration from Smalltalk yet utilizing a syntax reminiscent of C, it blends aspects of procedural, functional, and object-oriented programming paradigms. With a multitude of approaches for tackling any programming challenge, it remains flexible and doesn’t enforce strict preferences. Its weakly and dynamically typed nature, coupled with a complex type coercion system, can be challenging even for seasoned developers.

JavaScript isn’t without its shortcomings, peculiarities, and potentially problematic features. Beginners often grapple with concepts like asynchronicity, closures, and hoisting. Programmers familiar with other languages often make incorrect assumptions about how similarly named features function in JavaScript. For instance, arrays don’t behave exactly like arrays, the purpose of this can be unclear, and the role of prototypes and the new keyword can be puzzling.

The Issue with ES6 Classes

Among its more problematic features, the most troublesome is a recent addition in ECMAScript 6 (ES6): classes. Some discussions about classes reveal a fundamental misunderstanding of the language’s mechanics:

“With the introduction of classes, JavaScript is now a true object-oriented language!"

Or:

“Classes liberate us from the flawed inheritance model of JavaScript."

Or even:

“Classes provide a more reliable and user-friendly approach to creating types in JavaScript.”

These statements are concerning not because they suggest flaws in prototypical inheritance, but because they are inaccurate and highlight how JavaScript’s “something for everyone” philosophy can hinder a programmer’s comprehension. Let’s illustrate this with an example.

JavaScript Pop Quiz #1: What’s the Fundamental Difference Between These Code Blocks?

| |

| |

The answer is there is none. Both achieve the same outcome; the only difference is the use of ES6 class syntax.

While the second example might be considered more expressive, the issue runs deeper than syntax.

JavaScript Pop Quiz #2: What Is the Output of the Following Code?

| |

The correct answer is that it prints the following to the console:

| |

An incorrect answer suggests a misunderstanding of class in JavaScript. This is not a personal failing. Like Array, class is not a fundamental language feature but rather syntactic sugar. It aims to conceal the prototypical inheritance model and its associated complexities, creating an illusion of functionality that isn’t truly present.

You might have heard that class was introduced to make JavaScript more approachable for developers coming from classical OOP languages like Java. If you are one such developer, the previous example likely raised concerns, as it should. It reveals that JavaScript’s class keyword lacks the guarantees typically associated with classes and highlights a key difference in the prototype inheritance model: Prototypes are object instances, not types.

Comparing JavaScript Prototypes and Classes

The most crucial distinction between class-based and prototype-based inheritance in JavaScript lies in how they define structure. A class establishes a type that can be instantiated during runtime, while a prototype is itself an active object instance.

A subclass (child) of an ES6 class represents a new type definition, inheriting and extending the parent’s properties and methods. In contrast, a child of a prototype is another object instance that relies on the parent for any properties not defined within itself.

Side note: The reason for mentioning class methods but not prototype methods is that JavaScript lacks a distinct concept of methods. In JavaScript, functions are first-class, and they can possess properties or belong to other objects.

A class constructor is used to create an instance of that class. In JavaScript, a constructor is simply a function designed to return an object. Its uniqueness lies in its behavior when called with the new keyword, which assigns the constructor’s prototype to the returned object. If this sounds a bit complicated, you’re not alone – it’s a significant reason why prototypes are often misunderstood.

To emphasize, a child of a prototype is neither a duplicate nor an object with the same structure as its prototype. It holds a live reference to the prototype, and any prototype property absent in the child becomes a one-way reference to a property of the same name on the prototype.

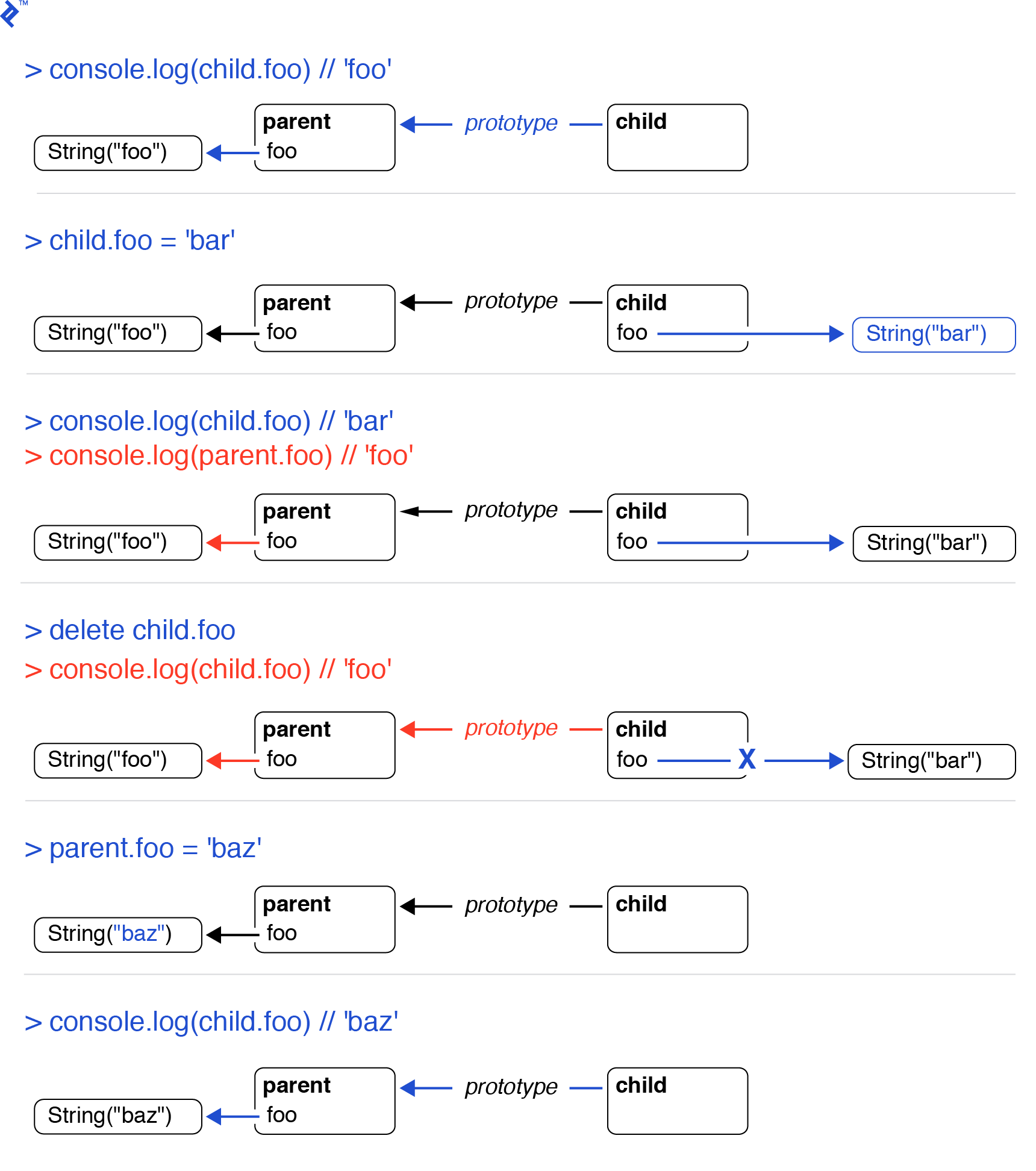

Consider the following code:

| |

In this example, child.foo initially referenced parent.foo while being undefined. When foo was defined on child, child.foo took on the value 'bar', but parent.foo retained its original value. After delete child.foo, it reverted to referencing parent.foo, inheriting any changes to the parent’s value.

Here’s a visual representation of how this unfolds (assuming Strings instead of string literals for clarity, though the difference is irrelevant here):

The internal workings of this mechanism, particularly the nuances of new and this, are a topic for another time. Mozilla offers a thorough article about JavaScript’s prototype inheritance chain for those eager to explore further.

The key takeaway is that prototypes do not define a type; they are themselves instances and remain modifiable during runtime, with all the implications and consequences that entails.

Now, let’s return to our analysis of JavaScript classes.

JavaScript Pop Quiz #3: How Is Privacy Implemented Within Classes?

Looking back, the properties in our prototype and class examples are exposed rather than truly “encapsulated.” How can we address this?

No code examples are provided for this. The answer is that you can’t.

JavaScript lacks a built-in concept of privacy but offers closures:

| |

Understanding what occurred here is crucial. If not, it indicates a need to grasp closures. Don’t worry – they’re not as daunting as they seem, are highly useful, and deserve further take some time to learn about them.

Let’s shift our focus to the other side of the JavaScript class versus function debate.

JavaScript Pop Quiz #4: How Can the Previous Example Be Replicated Using the class Keyword?

This is another trick question. While achievable, the implementation looks like this:

| |

Consider whether this appears clearer or simpler than the SecretiveProto approach. Personally, I find it somewhat less favorable – it deviates from conventional class usage in JavaScript and functions differently than one might anticipate, especially when compared to languages like Java. The following example illustrates this:

JavaScript Pop Quiz #5: What Does SecretiveClass::looseLips() Do?

Let’s find out:

| |

That’s not ideal.

JavaScript Pop Quiz #6: Which Do Seasoned JavaScript Developers Prefer: Prototypes or Classes?

As you might have guessed, this is another trick question. Experienced JavaScript developers often aim to avoid both whenever possible. Here’s an elegant solution using idiomatic JavaScript:

| |

This goes beyond merely evading inheritance complexities or enforcing encapsulation. Consider the possibilities with secretFactory and leaker that prototypes or classes might not easily offer.

For instance, destructuring becomes feasible due to the absence of this context concerns:

| |

This is quite convenient. Besides bypassing new and this intricacies, it ensures our objects work seamlessly with both CommonJS and ES6 modules. Composition also becomes more straightforward:

| |

Clients of blackHat remain oblivious to the origin of exfiltrate, and spyFactory avoids the complexities of Function::bind context management or deeply nested properties. While this might not pose significant issues in simple synchronous code, it can lead to complications in asynchronous scenarios, making its avoidance preferable.

With some ingenuity, spyFactory could evolve into a highly sophisticated tool capable of handling various infiltration targets – in other words, a façade.

Naturally, achieving this with a class, or rather a collection of classes inheriting from an abstract class or interface, is conceivable. However, JavaScript lacks the concept of abstracts or interfaces.

Let’s revisit the greeter example to see its factory-based implementation:

| |

You might have noticed the increasing conciseness of these factories. Don’t be alarmed; they function identically. Consider it a gradual removal of training wheels!

This approach already involves less boilerplate compared to prototypes or classes. Furthermore, it achieves more effective property encapsulation and potentially offers better memory and performance characteristics in some cases (thanks to the JIT compiler optimizing for reduced duplication and type inference).

Given its safety, potential speed, and coding ease, why revert to classes? One reason might be reusability. What if we desire unhappy and enthusiastic greeter variations? With the ClassicalGreeting class, the immediate inclination might be to establish a class hierarchy, parameterizing punctuation and creating subclasses:

| |

This seems reasonable until a feature request disrupts the hierarchy, rendering it nonsensical. Keep that in mind as we attempt the same functionality with factories:

| |

The improvement might not be immediately apparent, even with slightly shorter code. One could argue about readability and potential obtuseness. Why not simply have unhappyGreeterFactory and enthusiasticGreeterFactory?

Now, your client requests a greeter that is both unhappy and wants everyone to know it.

| |

If this enthusiastically unhappy greeter is needed more than once, simplification is possible:

| |

Similar composition styles can be achieved with prototypes or classes. For instance, UnhappyGreeting and EnthusiasticGreeting could be reimagined as decorators. This would still involve more boilerplate compared to the functional approach but would offer the safety and encapsulation of true classes.

However, JavaScript doesn’t provide such automatic safety. Frameworks relying heavily on class often employ “magic” to mask these issues and force JS classes into a semblance of proper behavior. Take a look at Polymer’s ElementMixin source code sometime; it’s a testament to the depths of JavaScript’s complexities.

While Object.freeze or Object.defineProperties can partially address some concerns, the question arises: Why mimic form without function while neglecting JavaScript’s native tools, tools that might not be present in languages like Java? Would you use a hammer labeled “screwdriver” when a real screwdriver is readily available?

Embracing the Strengths

JavaScript developers often focus on the language’s strengths, both informally and in reference to the book of the same name. The goal is to sidestep potential pitfalls arising from its design choices and leverage the aspects that facilitate clean, readable, error-resistant, and reusable code.

While opinions on which parts of JavaScript qualify as “good parts” may vary, I hope to have illustrated that class might not belong in that category. At the very least, it should be clear that inheritance in JavaScript can be complex, and class neither resolves this nor eliminates the need to understand prototypes. As a bonus, you might have noticed how object-oriented design patterns function perfectly well without classes or ES6 inheritance.

This isn’t to say class should be avoided entirely. Inheritance is sometimes necessary, and class provides cleaner syntax for it. Specifically, class X extends Y is undeniably more elegant than the traditional prototype approach. Moreover, many popular front-end frameworks encourage its use, and writing unconventional code should generally be avoided. However, the direction this trend is taking raises concerns.

A nightmare scenario involves a wave of JavaScript libraries built upon class with the flawed expectation of behavior mirroring other languages. New categories of bugs (pun intended) would emerge, and old ones thought to be eradicated could resurface. This “class” trap could plague experienced JavaScript developers, reminding us that popularity doesn’t always equate to quality.

In this bleak future, frustration might lead developers to abandon JavaScript and reinvent solutions in languages like Rust, Go, or Haskell, compiling to Wasm for web deployment. New web frameworks and libraries would proliferate in a multilingual chaos.

It’s a genuine concern that keeps me up at night.