Recent advancements in safeguarding online privacy include technologies like encrypted TLS server name indication (ESNI) and encrypted DNS, particularly DNS over HTTPS (DoH). These are generally seen as highly controversial by entities interested in collecting data.

Let’s delve into why these technologies are necessary, understand their workings, and explore the technical mechanisms behind them.

Ensuring Proper DNS Functionality

Numerous widely used technologies, such as Split-tunnel virtual private network (VPN) connections, the web proxy auto-discovery (WPAD) protocol, zero-configuration multicast DNS (mDNS), real-time blacklists (RBL), and many others, rely on the proper functioning of DNS. When DNS is compromised, these technologies can falter.

Exploiting the Internet for Profit and Recognition

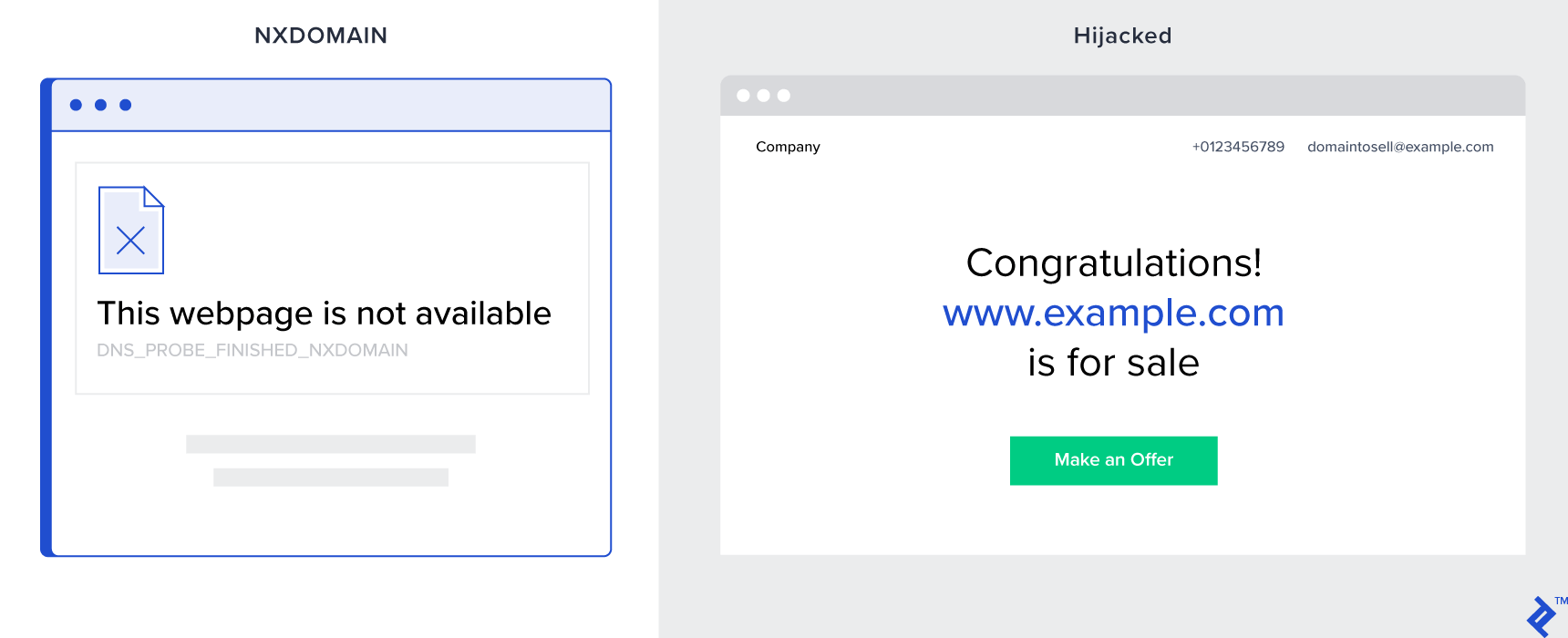

The critical importance of DNS on a global scale came to light as early as 2003. The company managing the .com top-level domain (TLD) at the time decided to cease issuing NXDOMAIN responses, choosing instead to mimic non-existent domains. This tactic aimed to display more ads, boost domain sales, and ultimately, drive revenue. However, this move triggered unintended consequences, igniting public discourse and leading to a damning report from ICANN’s Security and Stability Advisory Committee (SSAC). While the project was eventually shut down, the underlying technical vulnerability remained unaddressed.

Fast forward to 2008, another instance of DNS manipulation for profit surfaced. Several major ISPs introduced vulnerabilities that opened the door to cross-site scripting attacks, potentially impacting any website. The nature of these vulnerabilities even put websites hosted on private networks, inaccessible from the public internet, at risk of exploitation.

This issue doesn’t stem from flaws in core internet protocols but rather from the inappropriate monetization of specific DNS features. This exacerbates the problem.

Paul Vixie, Internet Systems Consortium (ISC)

While the protocols themselves might not be the root cause, they lack mechanisms to prevent malicious actors from exploiting the system. This means that, technically speaking, the vulnerability persisted.

Leveraging the Internet for Surveillance and Censorship

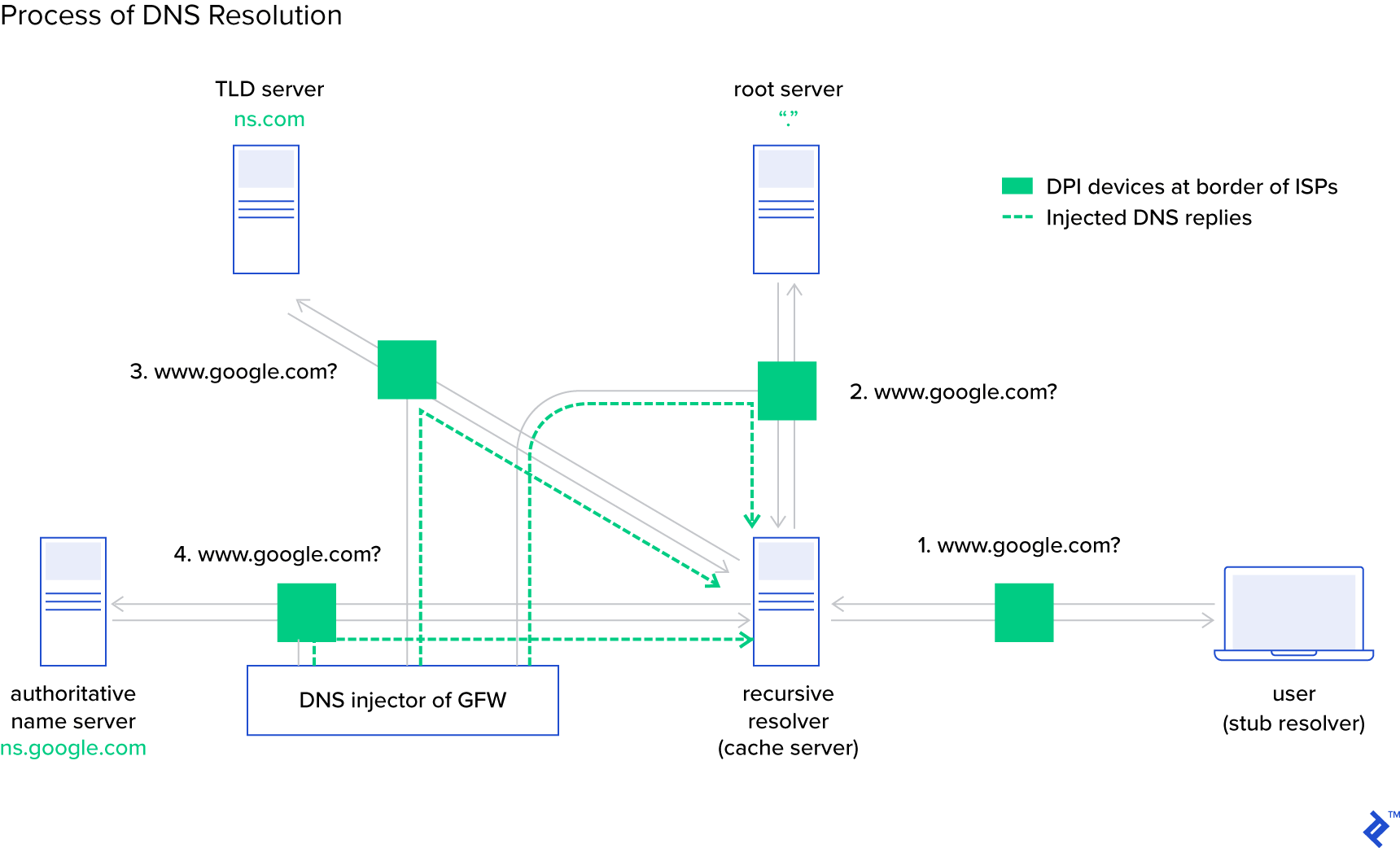

In 2016, it came to light that ISPs in Iran were manipulating DNS, but this time, instead of injecting ads, they were blocking access to the email servers of 139 out of the top 10,000 domains specific parts of the internet. Whether this was a deliberate denial-of-service tactic against certain domains—akin to the world-renowned censorship in China—or a consequence of flawed implementation in their DNS interception system, remains unclear.

See also:

The ambiguity surrounding the reasons behind DNS interception is crucial. Even if we disregard the ethical and legal implications of widespread surveillance and censorship, the technology employed for such purposes inherently deviates from established standards. Consequently, it could disrupt regular, legitimate internet usage.

Yet, the underlying technical vulnerability persisted.

Exploiting the Internet for Malicious Ends

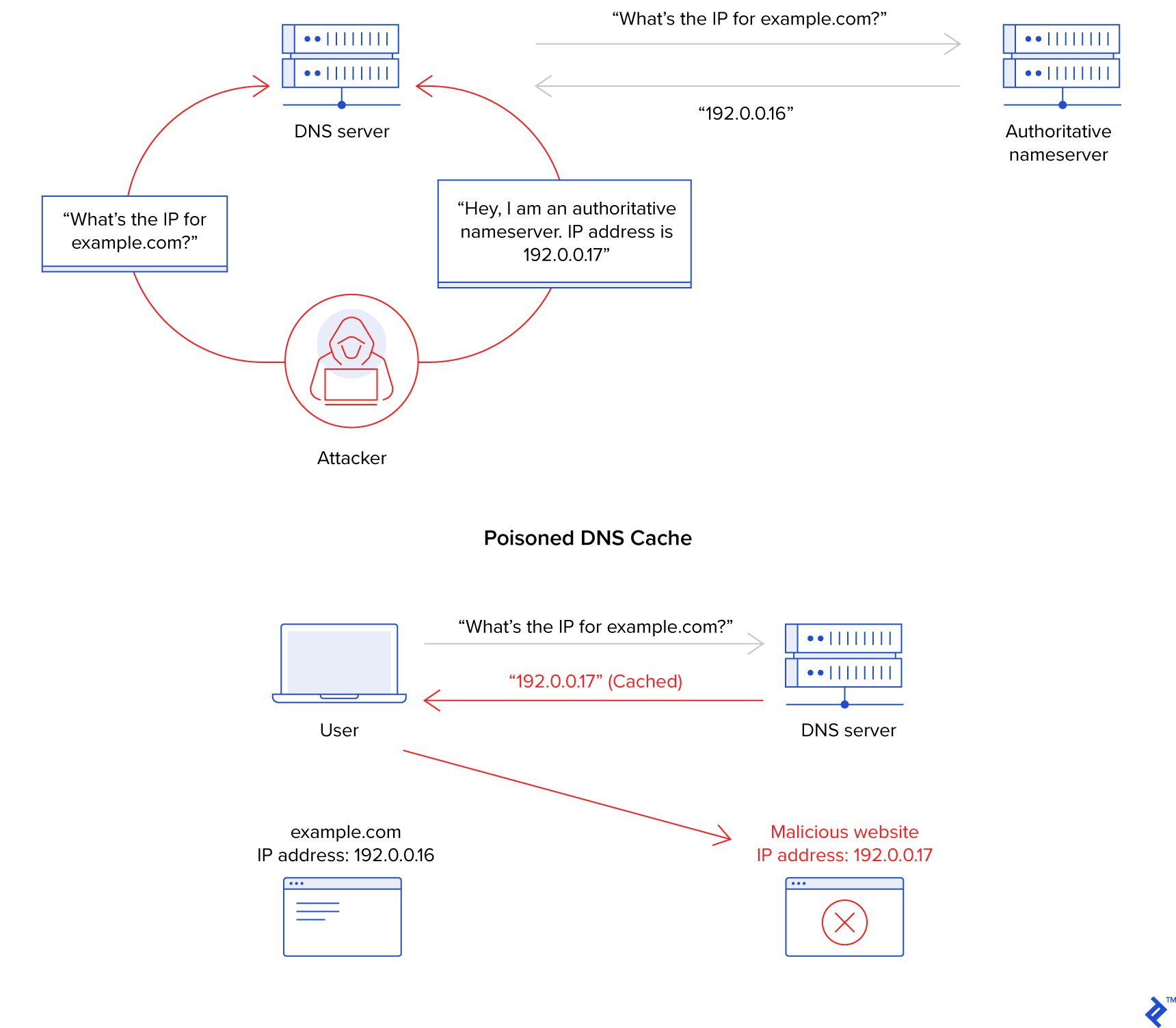

Attempts to intercept internet traffic for personal gain are not limited to corporations and governments. Numerous cases involve criminals trying to hijack connections, often to steal user information or deceive them into divulging sensitive login credentials. One prevalent example is the use of DNS cache poisoning to redirect users to phishing websites, enabling deploy ransomware, deploy botnets, deny service to specific websites, among other malicious activities.

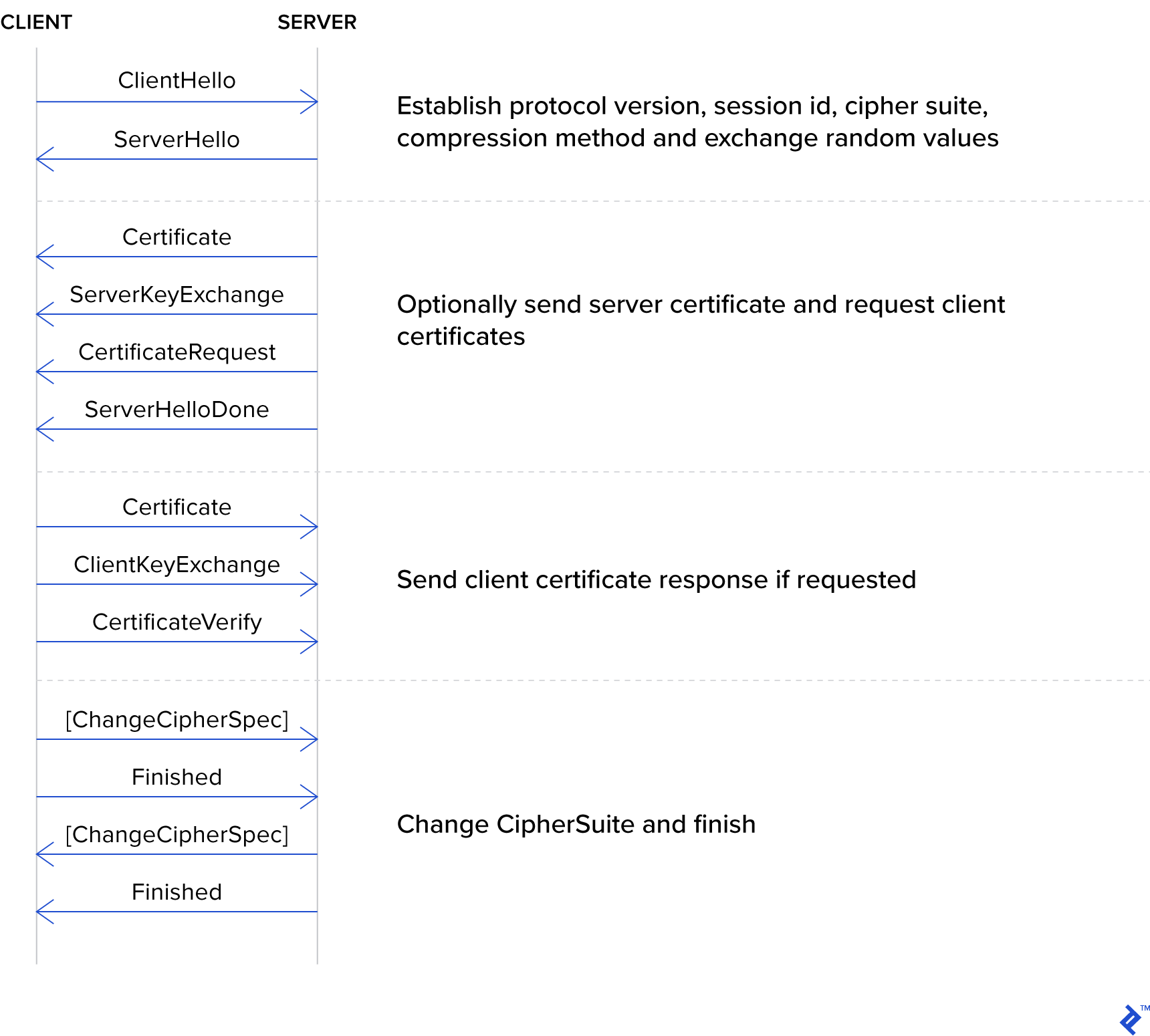

TLS: Exposing Connections

Transport Layer Security (TLS) forms the bedrock of HTTPS, the secure version of HTTP we rely on daily. Establishing a TLS connection involves several steps, including the server verifying its identity with a certificate and the exchange of new encryption keys.

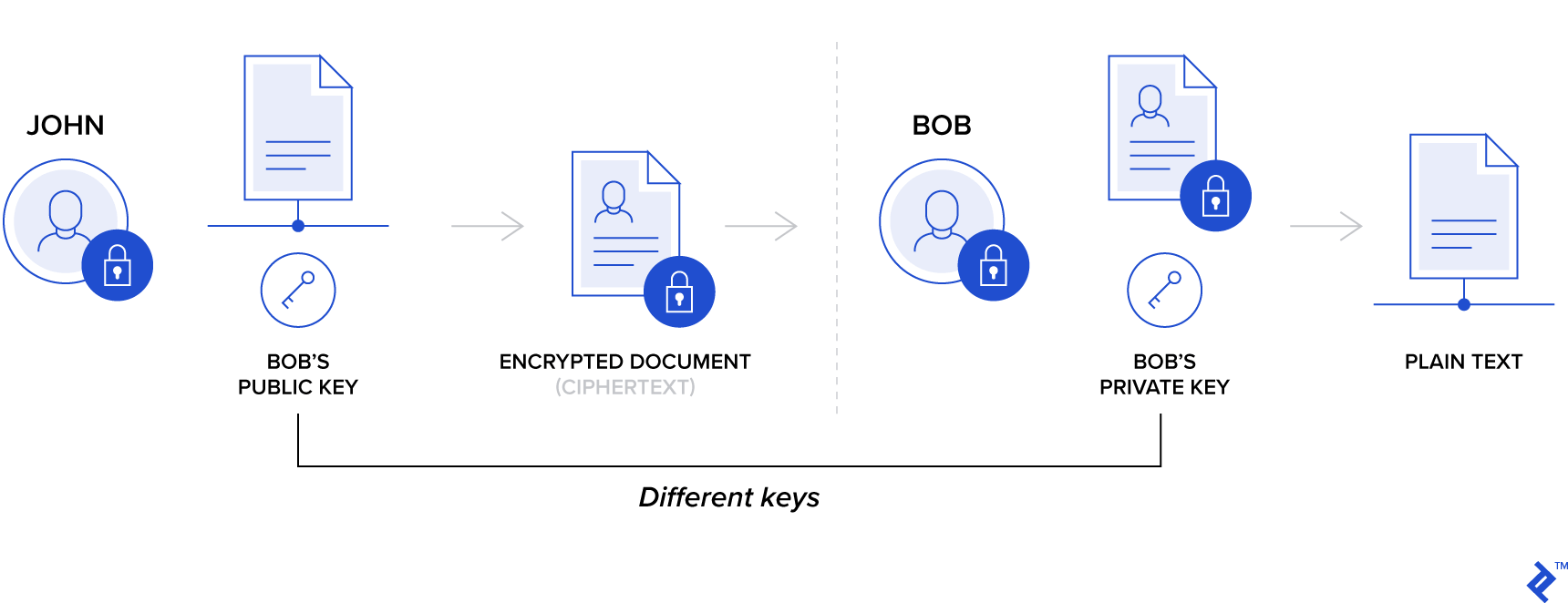

Server identity verification using a certificate is paramount. The certificate contains an asymmetric public encryption key.

When a client sends a message encrypted with this public key, only the server possessing the corresponding private key can decrypt it. This mechanism ensures that any entity intercepting or eavesdropping on the connection cannot decipher the content.

However, the initial exchange occurs in plain text without encryption, revealing the server’s identity to observers.

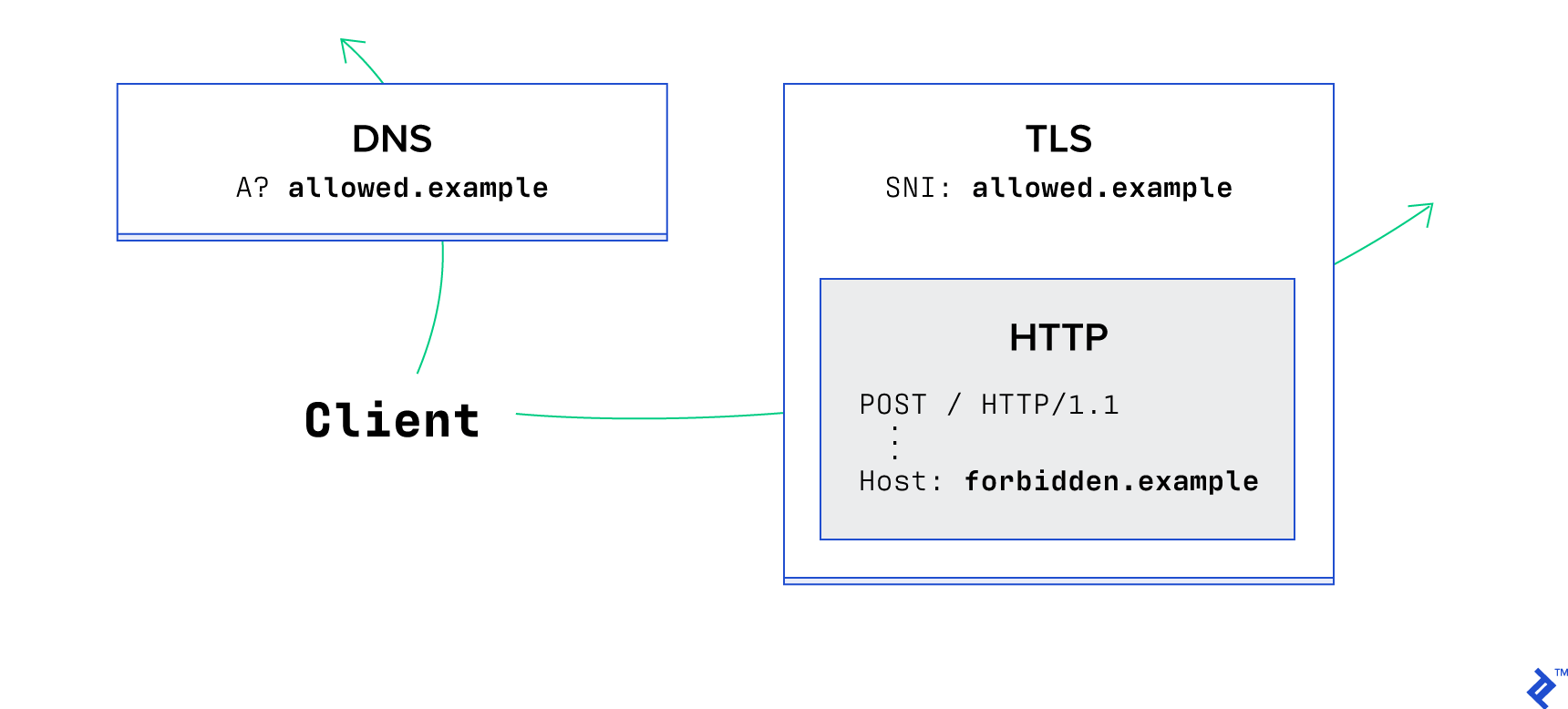

Domain Fronting

Some anti-censorship tools](https://signal.org/blog/looking-back-on-the-front/) temporarily circumvented this TLS vulnerability using a technique called domain fronting. This method exploited the fact that many large hosting providers didn’t verify if the hostname in each [HTTP request matched the one used during the TLS handshake, once an HTTPS connection was established. While privacy tools viewed this as a beneficial feature for discreet communication with hidden sites, hosting providers and data collectors saw it as an exploitation of implementation loopholes in the specification.

This, in itself, constituted a vulnerability. Several major hosting providers have since rectified this, including AWS such loopholes.

Resolving the Issue Through Standard Modification: Encrypted SNI (ESNI)

ESNI aims to prevent TLS data leakage by encrypting all communications, including the initial Client Hello message. This effectively blinds any observer to the server certificate being presented.

To achieve this, the client requires an encryption key prior to establishing a connection. Consequently, ESNI mandates the inclusion of specific ESNI encryption keys in an SRV record within DNS.

The precise details remain in development, as the the specification is still under finalization. Nevertheless, Mozilla Firefox and Cloudflare have already deployed an ESNI implementation.

Fortifying DNS Security and Encryption

Protecting against DNS tampering is crucial for the secure delivery of ESNI keys.

Efforts to secure DNS date back to 1993. Early IETF discussions revolved around:

- Safeguarding DNS data from unauthorized access.

- Ensuring data integrity.

- Authenticating data origin.

These discussions culminated in the Domain Name System Security Extensions (DNSSEC) standard in 1997. The standard tackled two out of these three concerns, with the design team consciously excluding data disclosure threats from its scope.

Therefore, DNSSEC primarily enables users to trust that the answers to their DNS queries are what domain owners intend them to be. In the context of ESNI, this verifies the integrity of the received key. Thankfully, DNSSEC mitigates many of the vulnerabilities outlined earlier. However, it doesn’t guarantee privacy, leaving it susceptible to surveillance and censorship.

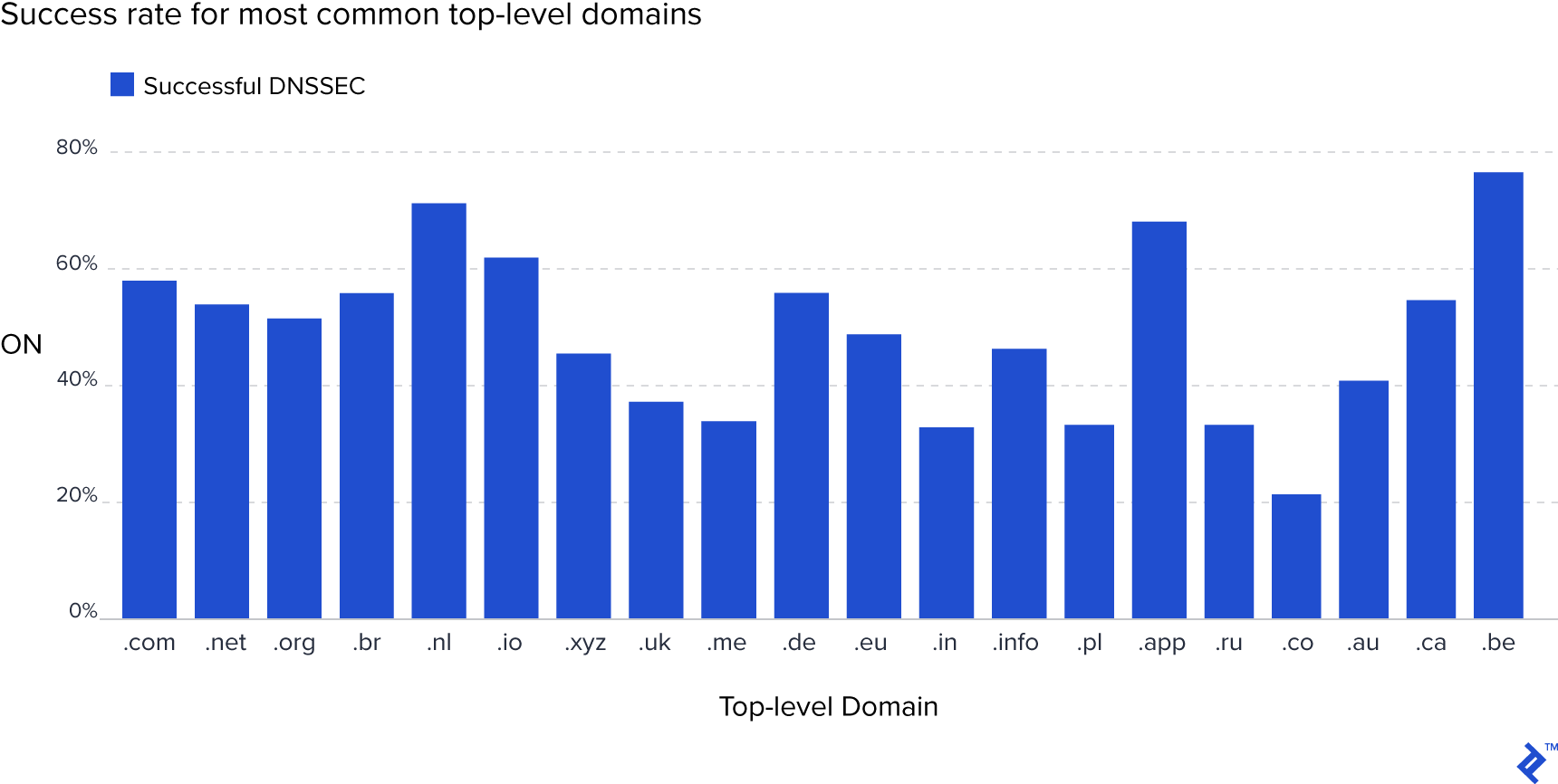

Unfortunately, due to its backward compatibility with “insecure DNS” and the complexity of its implementation, adoption of DNSSEC is very low. Many domain owners abandon the configuration process midway, as evidenced by numerous incomplete and invalid configurations observed in practical use.

DNS over HTTPS (DoH)

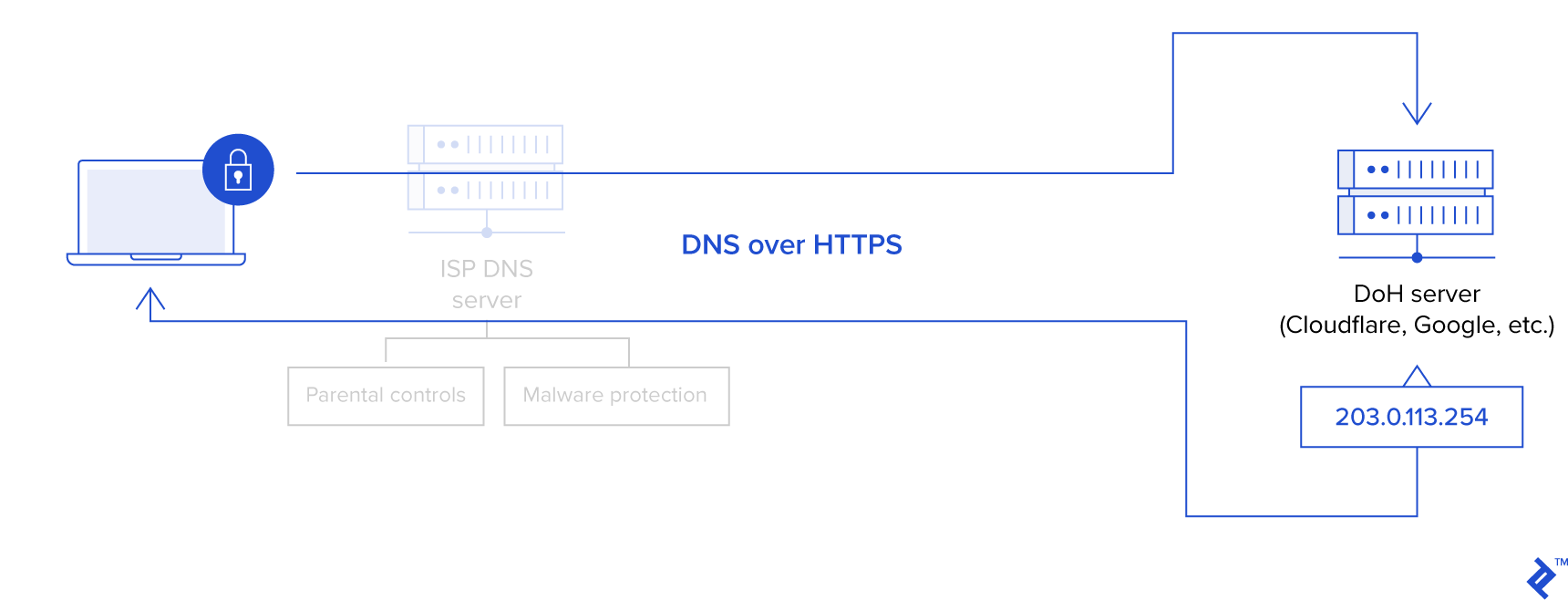

Protecting against DNS eavesdropping is paramount for delivering ESNI keys without revealing the user’s intended destination. Hence, encrypted DNS, such as DoH, emerges as a logical and desirable solution. However, DNS remains unencrypted as of today.

Efforts are underway by Mozilla, Google, APNIC, Cloudflare, Microsoft, and others to change this.

The Ideal Encrypted User Experience

Users seeking to utilize these technologies might have a comprehensive list of practical UX requirements when it comes to encryption. They would likely prefer to avoid:

- Mandated use of specific DNS service providers (regardless of their quality), or having the choice obscured or difficult to locate.

- Inconsistent DNS handling across apps on a device (e.g., Firefox resolving addresses that Safari cannot).

- The need for all apps on a device to create its own secure DNS implementation internally.

- Multiple instances of manually configure DNS.

- An opt-in approach to privacy and security.

- Apps reverting to insecure operation without user consent.

Privacy-conscious users, on the other hand, would prioritize:

- Protection from unwarranted surveillance by any entity.

- Shielding from targeted advertising without explicit consent.

- Ensuring the integrity of their published content (e.g., on personal websites) against alteration or manipulation during transmission.

- Guaranteeing that individuals accessing their published content do not face repercussions simply for doing so.

- Retaining control over DNS on their networks (because sometimes, split-horizon DNS is beneficial for restricting internal resources to internal users).

- The ability to opt into, or at the very least, opt out of, filtering at the DNS level (e.g., Quad9, CleanBrowsing, and OpenDNS Family Shield).

- Straightforward and effortless configuration (i.e., DHCP).

- Explicit consent requests for using unencrypted DNS.

- Extending protection beyond browser traffic to encompass all traffic types, including email, Slack, VoIP, SSH, VPN, etc.

Current Encryption Initiatives

What choices are available to users with these objectives?

Mozilla’s solution, while a step in the right direction, falls short of ideal. Their approach focuses solely on securing Firefox](https://www.mozilla.org/en-GB/firefox/new/), with the default behavior overriding OS settings to prioritize their chosen provider ([Cloudflare) without explicit user notification. Furthermore, it silently reverts to insecure modes (e.g., when encrypted DNS is blocked).

Google’s solution presents a more favorable approach. They are securing Android 9+, which encompasses all apps. (Their plans for Chrome OS remain unclear, but it’s reasonable to anticipate developments in that area.) Additionally, they are securing Chrome across platforms. However, this security enhancement only activates when the host platform is configured to use a provider supporting those security features. While this respects user choice, it’s not ideal as it silently falls back to insecure modes.

Other major browsers are also implementing support similar initiatives.

Ideally, the broader software and OS development community would:

- Shift away from implementing new DNS security features at the application level.

- Prioritize implementation at the OS level.

- Respect OS-level configurations or obtain explicit user consent.

By implementing encrypted DNS at the OS level, we can maintain the existing distributed model for DNS resolvers. Users should retain the option to run their own secure DNS servers on their networks, alongside the choice of using centralized providers.

Linux and BSD already offer this functionality with a range of available options. Regrettably, to my knowledge, no distribution enables these features by default. Explore options like nss-tls for solutions that integrate seamlessly with glibc.

Google’s DNS-over-TLS implementation in Android 9+ also follows this approach. It tests DNS servers for encryption support, utilizing it if available. Similar to Chrome, if encryption isn’t supported, it proceeds insecurely without prompting for user consent.

It’s important to acknowledge that most networks default to using DNS servers lacking encryption support. Consequently, the solution integrated into Android doesn’t yet impact the majority of users. A potential improvement could involve offering a fallback to centralized encrypted DNS when decentralized options lack encryption support.

As of now, official support for encrypted DNS on Apple and Microsoft devices is pending. With the release of Microsoft having announced in November 2019 their intentions to support encrypted DNS, hopefully, Apple will follow suit soon.

Encrypted DNS Workarounds

Several workarounds exist in the form of locally run proxies. These proxies allow a user’s computer to communicate using unencrypted DNS internally while using encrypted DNS for communication with the configured external provider. While not a perfect solution, it serves as a reasonable workaround.

This article was inspired by the DNSCrypt proxy proxy, known for its stability, comprehensive features, and cross-platform nature. It supports both older protocols like DNSCrypt protocol and newer ones like DNS over TLS (DoT) and DNS over HTTPS (DoH).

Windows users have access to installer and GUI called Simple DNSCrypt, a user-friendly and feature-rich option.

I recommend these workarounds but caution that widespread adoption might take time. Be prepared to disable them occasionally, such as when connecting to captive portals at cafes or during LAN parties.

Additional Choices

Another noteworthy option is Technitium DNS Server, which supports encrypted DNS, boasts cross-platform compatibility (Windows, MacOS, Linux on ARM/Raspberry Pi) and a user-friendly web interface. It falls under the “other” category because it functions as a comprehensive tool rather than a solution specifically addressing this issue. (It could be a suitable choice for running a Raspberry Pi DNS server at home. I’d appreciate feedback from anyone who tries it in the comments below.)

For users with Android or iOS (iPhone, iPad, etc.) devices, the 1.1.1.1 app is an option. This app routes all DNS queries through the Cloudflare Encrypted DNS service. I’ve heard positive things about more versatile alternatives like Intra, though I haven’t personally tested them yet.

Of course, enabling encrypted DNS within both Firefox and Chrome remains an option, but remember the caveats discussed earlier.

DNS Reliability: The Top Priority

Internet privacy technologies often spark debate. However, the primary goal of implementing security and privacy measures isn’t solely about secrecy. It’s about ensuring the reliability and proper functioning of technology, irrespective of external factors. Nonetheless, it’s crucial to remember that just as technology lacking privacy safeguards is detrimental, poorly implemented safeguards can exacerbate existing issues.