Combining multiple models, known as ensemble methods, often leads to more accurate results in machine learning compared to using a single model. This approach has proven successful in numerous machine learning competitions, including the Netflix Competition where the winner used an ensemble method to create a powerful collaborative filtering algorithm. Similarly, the winner of KDD 2009 also utilized used ensembling. Further evidence of their effectiveness can be found in Kaggle competitions, such as here, which is an interview with the winner of CrowdFlower competition.

Before delving further, let’s clarify some terminology. In this article, the term “model” refers to the output generated by an algorithm trained on data. This model is then utilized for making predictions. The algorithm itself can be any machine learning algorithm, including logistic regression, decision trees, and others. These models, when used as input for ensemble methods, are referred to as “base models,” with the final output being an “ensemble model.”

This blog post focuses on ensemble methods for classification, exploring popular methods like voting, stacking, bagging, and boosting.

Combining Predictions with Voting and Averaging

Voting and averaging are straightforward ensemble learning techniques in machine learning. Both are easy to grasp and implement, with voting used for classification and averaging for regression.

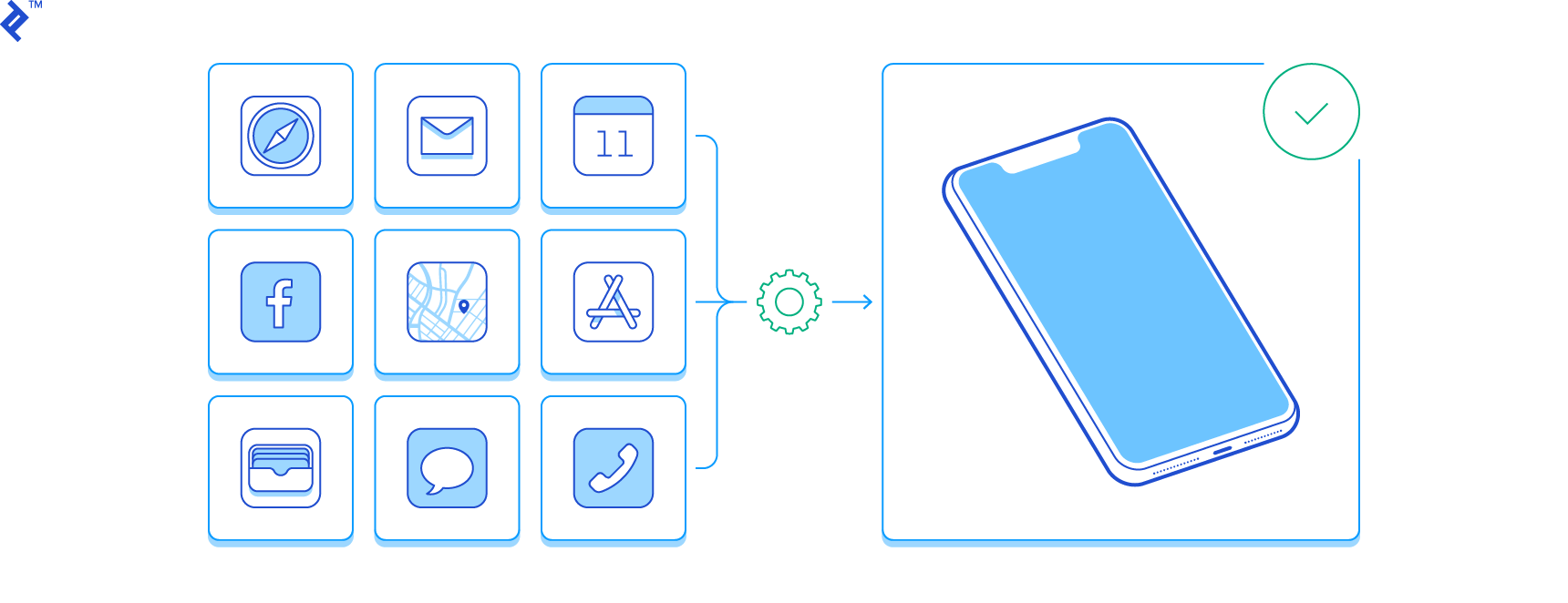

The initial step in both methods involves creating multiple classification/regression models using a training dataset. Each base model can be trained using different subsets of the training data with the same algorithm, the same dataset with different algorithms, or any other approach. The Python-like pseudocode below illustrates using the same training dataset with different algorithms:

| |

This pseudocode generates predictions from each model and stores them in a matrix called “predictions,” where each column holds the predictions of a single model.

Majority Voting

Each model makes a prediction (vote) for every test instance. The final prediction is the one that receives over half of the votes. If no prediction gets a majority, the ensemble method might be considered inconclusive for that instance. While this is a common technique, using the most voted prediction, even if less than half, can be considered as the final prediction. This variation is sometimes called “plurality voting.”

Weighted Voting

Unlike majority voting, where each model has equal weight, the importance of certain models can be amplified. Weighted voting gives more weight to the predictions of better-performing models. Determining suitable weights is subjective and depends on the specific problem.

Simple Averaging

In simple averaging, the average prediction across all models is calculated for each test instance. This method often reduces overfitting, resulting in a smoother regression model. The following pseudocode demonstrates simple averaging:

| |

Weighted Averaging

This is a modification of simple averaging where each model’s prediction is multiplied by its assigned weight before calculating the average. Here’s the pseudocode for weighted averaging:

| |

Stacking Machine Learning Models

Stacking, also called stacked generalization, combines models using another machine learning algorithm. Trained on the initial training data, base algorithms generate a new dataset based on their predictions. This new dataset then serves as input for a combiner machine learning algorithm.

The pseudocode for stacking is as follows:

| |

As shown, the combiner algorithm’s training data comes from the base algorithms’ outputs. In this example, the base algorithms are trained and then used to make predictions on the same dataset. However, in real-world scenarios, using the same data for training and prediction is not ideal. To address this, some stacking implementations split the training data. The following pseudocode shows how to split the training data before training the base algorithms:

| |

Bootstrap Aggregating (Bagging)

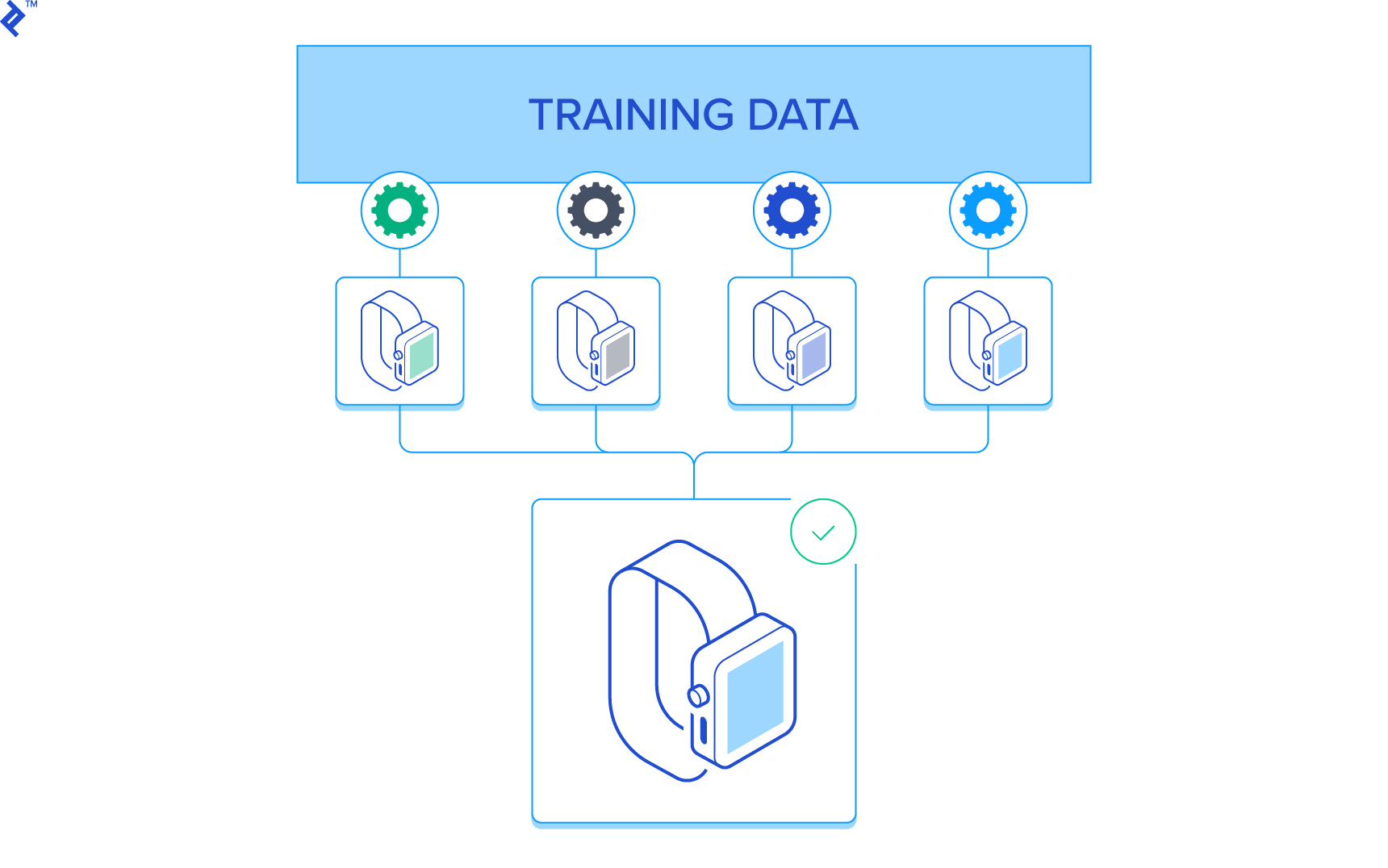

Bagging involves creating multiple models using the same algorithm but with different random sub-samples of the original dataset. These sub-samples are created using bootstrap sampling, where some original data points may appear multiple times while others might be absent. To create a sub-dataset with “m” elements, randomly select “m” elements from the original dataset with replacement. Repeat this process “n” times to generate “n” datasets.

This results in “n” datasets, each containing “m” elements. The following Python-esque pseudocode demonstrates bootstrap sampling:

| |

The next step in bagging is aggregating the predictions of these models, often using methods like voting or averaging.

The complete pseudocode for bagging is as follows:

| |

Since each sub-sample in bagging is independent, their generation and model training can be done in parallel.

Some algorithms inherently utilize bagging. For instance, the Random Forest algorithm uses a variation of bagging with random feature selection and decision trees as its base algorithm.

Boosting: From Weak to Strong Models

Boosting encompasses algorithms that transform weak models into strong ones. A model is considered weak if it has a significant error rate but still performs better than random guessing (which would result in an error rate of 0.5 for binary classification). Boosting iteratively builds an ensemble, training each model on the same dataset but with instance weights adjusted based on the previous model’s errors. This focuses the models on challenging instances. Unlike bagging, boosting is sequential, limiting parallel operations.

The general boosting algorithm procedure is:

| |

The “adjust_dataset” function identifies and returns a new dataset containing the most challenging instances, prompting the base algorithm to learn from them.

AdaBoost, a popular boosting algorithm, earned its creators the Gödel Prize. Decision trees are commonly used as the base algorithm for AdaBoost, with sklearn using it as the default (AdaBoostRegressor and AdaBoostClassifier). AdaBoost employs the same incremental approach discussed earlier, using information about each training sample’s difficulty from each step. However, the “adjusting dataset” step differs from the previous description, and the “combining models” step uses weighted voting.

Conclusion

While powerful and capable of achieving high accuracy, ensemble methods might not always be suitable for industries prioritizing interpretability over raw performance. Nevertheless, their effectiveness is undeniable and can be invaluable in the right applications. For instance, in healthcare, even slight improvements in machine learning model accuracy can have significant positive implications.