Programmers often classify programming languages into paradigms like object-oriented, imperative, and functional. This helps in identifying languages suitable for similar tasks. However, while languages like Elixir (and Erlang before it) share characteristics with functional languages, their reliance on OTP suggests a distinct process-oriented paradigm.

This article delves into process-oriented programming using these languages, contrasting it with other paradigms and highlighting its implications for learning and practical application. We’ll conclude with a concise process-oriented programming illustration.

Defining Process-oriented Programming

Process-oriented programming, rooted in Communicating Sequential Processes from a 1977 paper by Tony Hoare (also known as the actor model), prioritizes the structure and interaction of processes within a system. Languages like Occam, Limbo, and Go share similarities with this model. While the original concept focused on synchronous communication, many, including OTP, utilize asynchronous communication as well. OTP, built on this foundation, enables fault-tolerant systems through communicating sequential processes. Its “let it fail” philosophy, coupled with robust error recovery via supervisors and distributed processing, proves more reliable than the “prevent it from failing” approach.

In essence, process-oriented programming emphasizes the structure and communication channels of processes as the core aspects of system design.

Comparing Paradigms

Object-oriented vs. Process-oriented

Object-oriented programming revolves around the organization of data and functions within objects and classes. UML class diagrams epitomize this focus, as depicted in Figure 1.

A common criticism of object-oriented programming is the lack of clear control flow visibility, especially in complex systems. Conversely, its strength lies in the ease of extending systems with new object types that adhere to established conventions.

Functional vs. Process-oriented

Functional programming prioritizes immutable data and function manipulation. While many handle concurrency, their primary scope remains within a single address space. Communication between executables typically relies on operating system-specific methods.

Take Scala is a functional language, for example. Its foundation on the Java Virtual Machine allows access to Java’s communication features, but this isn’t inherent to the language. Similarly, its use in Spark is through a library.

Functional programming excels in control flow visualization due to its explicit function calls and lack of side effects. However, managing persistent state, crucial for real-world applications, poses a challenge. Well-designed functional systems handle this at the top level, preserving side-effect-free operation for most components.

Elixir/OTP and Process-oriented Programming

In Elixir/Erlang and OTP, communication primitives are integral to the virtual machine. Inter-process and inter-machine communication are fundamental, emphasizing the paramount importance of communication in this paradigm.

While Elixir’s logic is largely functional, its application is inherently process-oriented.

Understanding Process Orientation

Process-oriented design prioritizes identifying the types of processes needed and their interactions. Key considerations include process lifespan, system load, expected data volume and velocity. Only after addressing these factors does the logic within each process come into play.

Implications for Learning

Training should emphasize systems thinking and process allocation over language syntax. A deep understanding of OTP, lifecycle management, quality assurance, DevOps, and business needs is crucial.

Implications for Adoption

Process-oriented languages excel in distributed systems or those requiring extensive communication. They might be less suitable for single-workload, single-computer scenarios. Their inherent fault tolerance makes them ideal for long-running systems.

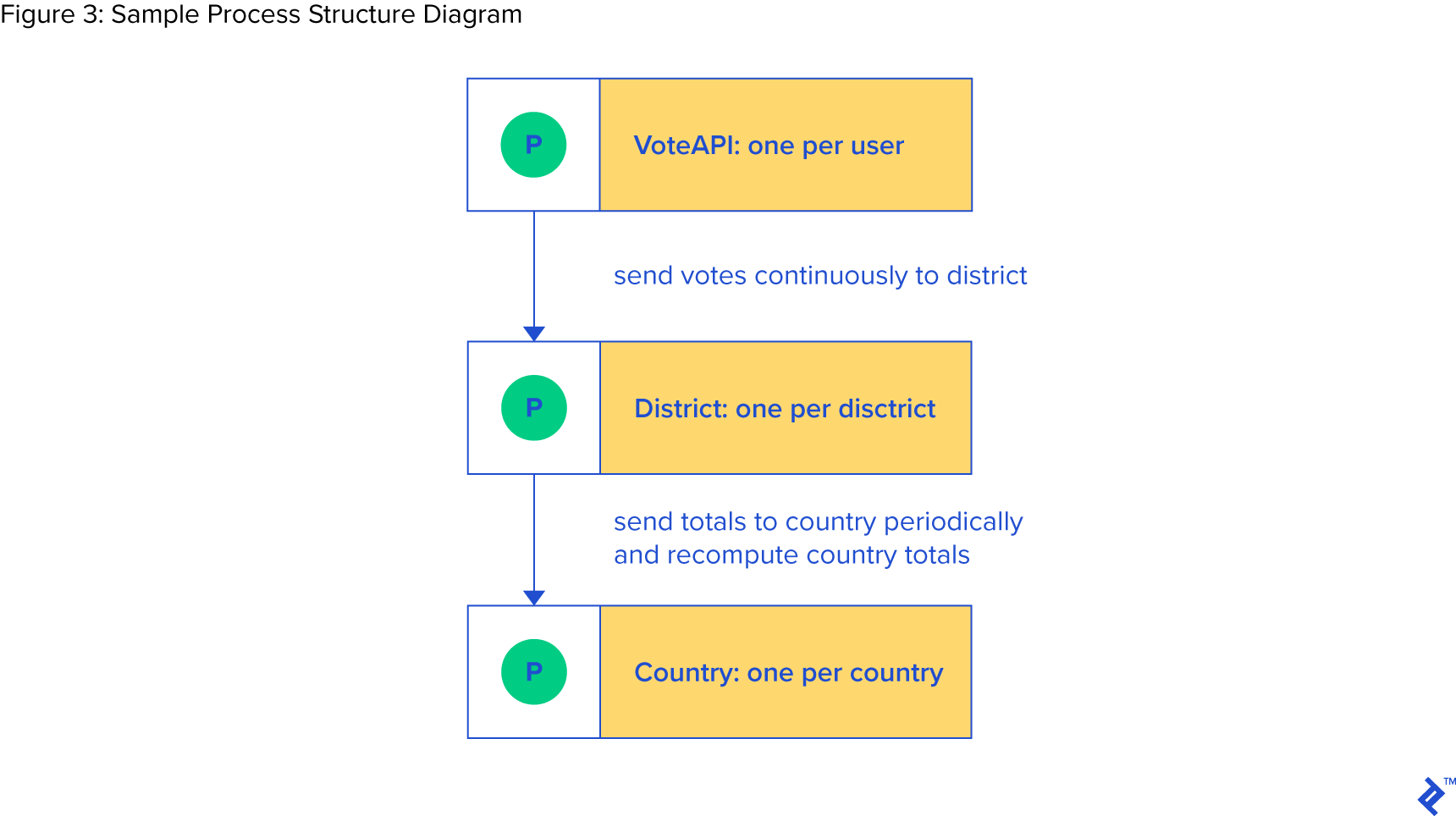

For documentation and design, sequence diagrams (Figure 2) effectively illustrate temporal relationships between processes. Simple box-and-arrow diagrams can represent process types and relationships (Figure 3).

A Process-oriented Example: Global Election System

Let’s design a system to manage global elections, handling vote casting, real-time aggregation, and result presentation.

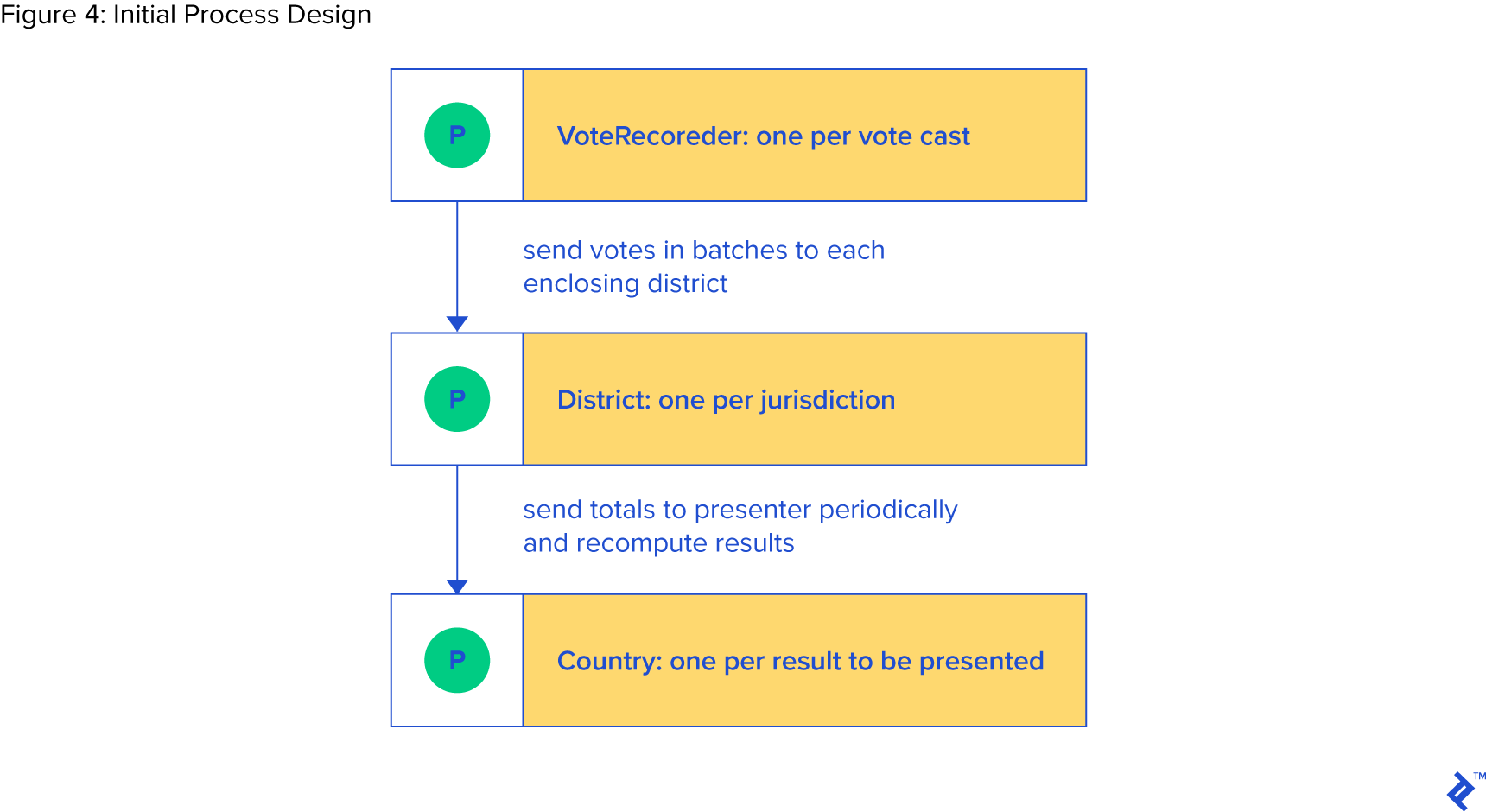

Initial Design

- Vote Collection: Numerous processes, potentially distributed geographically, receive and log votes, forwarding them in batches to aggregators.

- Vote Aggregation: Dedicated processes, potentially one per country and state/province, compute and hold real-time results.

- Result Presentation: Processes, possibly distributed geographically, cache and serve results to users, minimizing load on aggregators.

This initial process-agnostic design ensures scalability, geographic distribution, and data integrity through acknowledgments. (Figure 4)

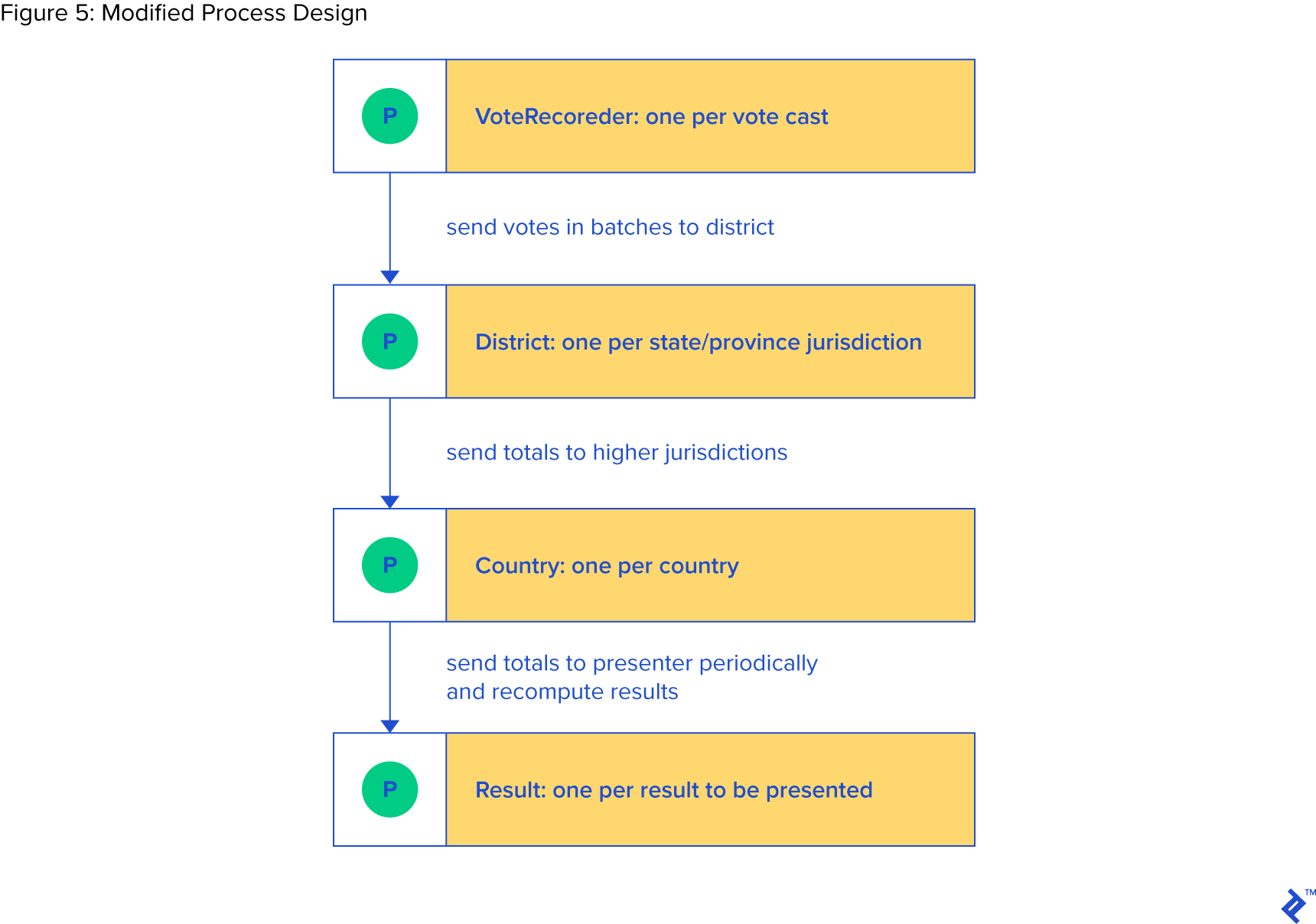

Incorporating Complexity

Introducing jurisdiction-specific rules for vote aggregation and result determination necessitates a revised process structure. Results from state/province aggregators now feed into country-level aggregators. Reusing the communication protocol allows logic reuse, but distinct processes and communication paths are required. (Figure 5)

Code Implementation

The following Elixir OTP code snippets demonstrate the example’s implementation, assuming a separate web server (e.g., Phoenix) handles user requests. Full source code with tests is available at https://github.com/technomage/voting.

Vote Recorder

| |

Vote Aggregator

| |

Result Presenter

| |

Conclusion

This exploration highlighted Elixir/OTP’s strength as a process-oriented language, comparing it to other paradigms and illustrating its practical application. The key takeaway: prioritize a process-centric design approach, considering system-level interactions before delving into code logic.

For those interested, the complete example code can be found on GitHub.