Grouping data points into clusters based solely on the characteristics of each sample is the goal of clustering, an unsupervised machine learning technique. By organizing data into clusters, we can discover previously unknown relationships between samples or identify outliers in a dataset. From marketing to biology, clustering is important in a wide range of industries. Its uses include market segmentation, social media analysis, and medical imaging for diagnosis.

Since this process is unsupervised, different clustering results can be generated based on different features. As an illustration, suppose you have a dataset containing numerous images of red trousers, black trousers, red shirts, and black shirts. One algorithm might identify clusters based on clothing shape, while another might group items according to color.

When examining a dataset, we need a way to reliably assess how well different clustering algorithms perform. We might want to compare the outputs of two algorithms or determine how similar a clustering outcome is to a desired result. We will examine several metrics that can be used to compare various clustering results from the same data in this article.

Clustering Explained: A Quick Example

Let’s establish a sample dataset that we’ll use to illustrate several clustering metric ideas and investigate the types of clusters it might produce.

First, a few common terms and notations:

- $D$: the data set

- $A$, $B$: two clusters that are subsets of our data set

- $C$: the ground truth clustering of $D$ that we will compare another cluster to

- Clustering $C$ has $K$ clusters, $C = {C_1, …, C_k}$

- $C’$: a second clustering of $D$

- Clustering $C’$ has $K’$ clusters, $C’ = {C^\prime_1, …, C^\prime_{k^\prime}}$

Clustering results can differ not only based on the features used for sorting, but also the total cluster count. The outcome is influenced by the algorithm used, its susceptibility to minor disturbances, the model’s parameters, and the characteristics of the data. Using our previously mentioned dataset of black and red trousers and shirts, we could get a variety of clustering results depending on the algorithm.

To differentiate between general clustering $C$ and our example clusterings, we will use a lowercase $c$ to denote our example clusterings:

- $c$, with clusters based on shape: $c = {c_1, c_2}$, where $c_1$ represents trousers and $c_2$ represents shirts

- $c’$, with clusters based on color: $c’ = {c’_1, c’_2}$, where $c’_1$ represents red clothes and $c’_2$ represents black clothes

- $c’’$, with clusters based on shape and color: $c’’ = {{c^{\prime \prime}}_1, {c^{\prime \prime}}_2, {c^{\prime \prime}}_3, {c^{\prime \prime}}_4}$, where ${c^{\prime \prime}}_1$ represents red trousers, ${c^{\prime \prime}}_2$ represents black trousers, ${c^{\prime \prime}}_3$ represents red shirts, and ${c^{\prime \prime}}_4$ represents black shirts

Additional clusterings might include more than four clusters based on various features, such as the presence or absence of sleeves in a shirt.

As demonstrated in our example, a clustering method separates every sample in a dataset into non-empty, separate subsets. In cluster $c$, no image can belong to both the trouser subset and the shirt subset: $c_1 \cap c_2 = \emptyset$. This idea can be expanded upon: no two subsets of any cluster share the same sample.

An Overview of Clustering Comparison Metrics

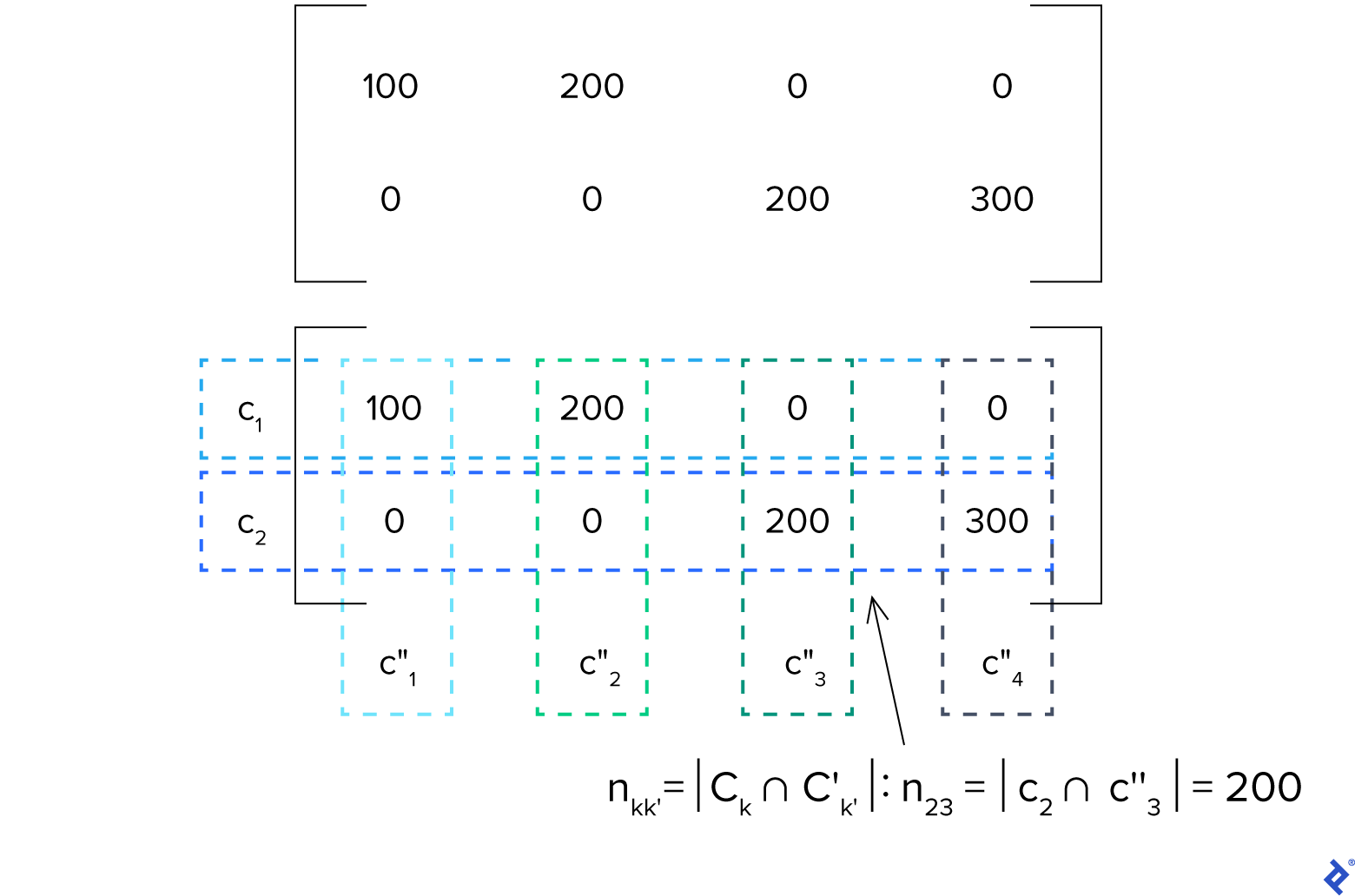

Most clustering comparison metrics can be defined using the confusion matrix for the pair $C, C’$. The confusion matrix would be a $K \times K’$ matrix whose $kk’$th element (the element in the $k$th row and $k’$th column) is the sample count in the intersection of clusters $C_k$ of $C$ and $C’_{k’}$ of $C’$:

[n_{kk’} = |C_k \cap C’_{k’}|]

Let’s analyze this using our simplified black and red trousers and shirts example, assuming that data set $D$ has 100 red trousers, 200 black trousers, 200 red shirts, and 300 black shirts. Let’s examine the confusion matrix of $c$ and $c’’$:

As $K = 2$ and $K’’ = 4$, this is a $2 \times 4$ matrix. Let’s assume that $k = 2$ and $k’’ = 3$. We can see that element $n_{kk’} = n_{23} = 200$. This indicates that the intersection of $c_2$ (shirts) and ${c^{\prime\prime}}_3$ (red shirts) is 200, which is accurate because $c_2 \cap {c^{\prime\prime}}_3$ would just be the set of red shirts.

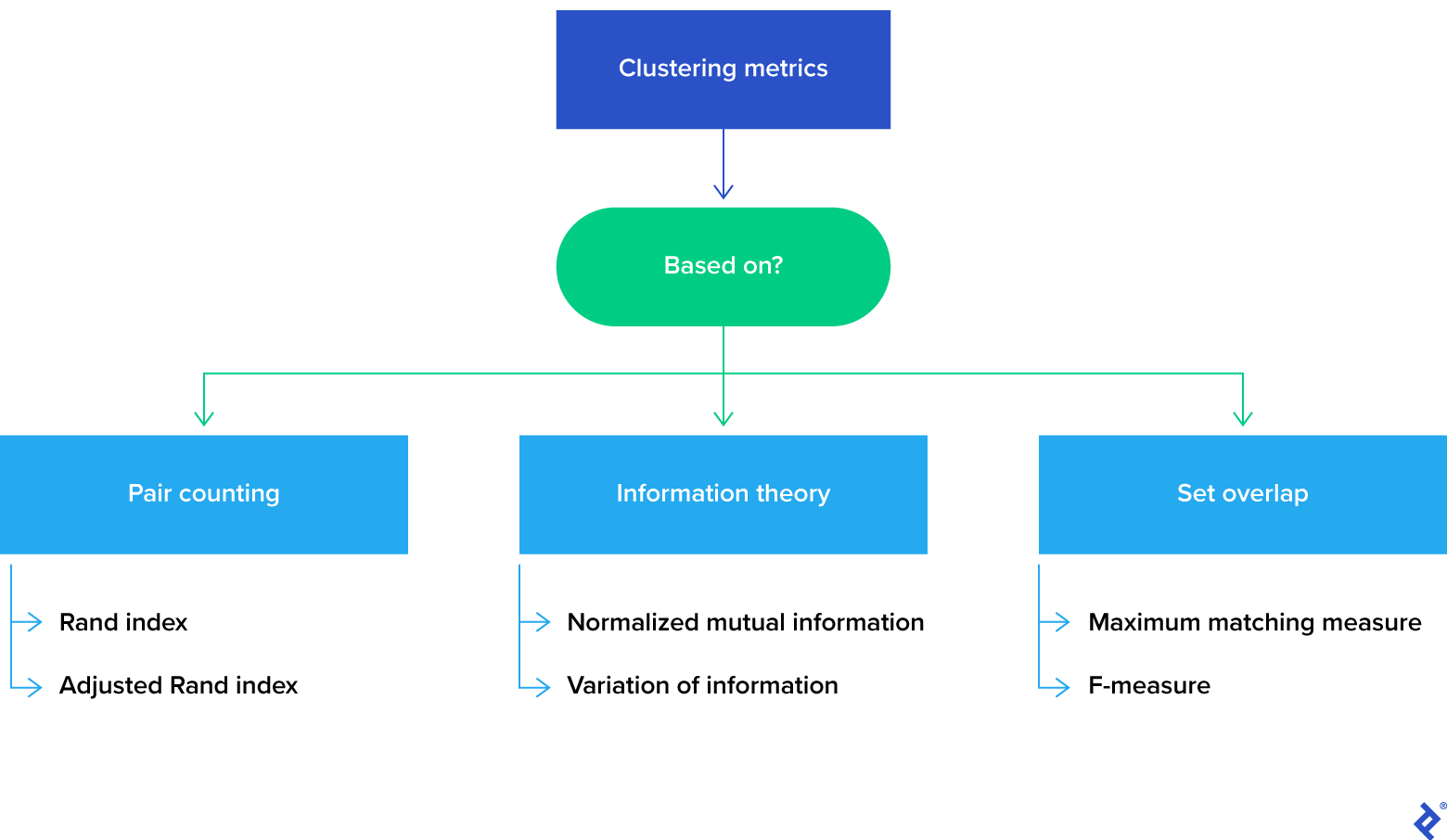

Clustering metrics can be broadly classified into three types based on the underlying method of cluster comparison:

We will only go over a few of the many metrics available in this article, but our examples will help to illustrate the three clustering metric categories.

Pair-Counting

Pair-counting involves looking at every pair of samples and tallying up the instances where the clusterings agree and disagree. Each pair of samples can fall into one of four sets, where set element counts ($N_{ij}$) are obtained from the confusion matrix:

- $S_{11}$, with $N_{11}$ elements: the pair’s elements are in the same cluster under both $C$ and $C’$

- When comparing $c$ and $c’’$, a pair of two red shirts would be classified as $S_{11}$.

- $S_{00}$, with $N_{00}$ elements: the pair’s elements are in different clusters under both $C$ and $C’$

- When comparing $c$ and $c’’$, a pair consisting of a red shirt and black trousers would fall under $S_{00}$.

- $S_{10}$, with $N_{10}$ elements: the pair’s elements are in the same cluster in $C$ but different clusters in $C’$

- When comparing $c$ and $c’’$, a red shirt and a black shirt would fall under $S_{10}$.

- $S_{01}$, with $N_{01}$ elements: the pair’s elements are in different clusters in $C$ but the same cluster in $C’$

- When comparing $c$ and $c’’$, $S_{01}$ is empty ($N_{01} = 0$).

The Rand index is calculated as $(N_{00} + N_{11})/(n(n-1)/2)$, where $n$ is the number of samples; it can also be interpreted as (number of similarly treated pairs)/(total number of pairs). Although its value theoretically ranges from 0 to 1, its practical range is usually much narrower. A larger value implies a stronger resemblance between the clusterings. (A Rand index of 1 would represent a perfect match, where the clusters in two clusterings are identical.)

One disadvantage of the Rand index is how it behaves as the cluster count grows to match the number of elements. When this happens, it approaches 1, making it difficult to precisely measure clustering similarity. Several enhanced or modified Rand indices have been developed to solve this problem. The adjusted Rand index is one such variation, but it operates under the presumption that two clusterings are selected randomly with a fixed number of clusters and cluster elements.

Information Theory

General information theory concepts form the basis of these metrics. We’ll talk about two of them: entropy and mutual information (MI).

Entropy quantifies the amount of information contained in a clustering. If a clustering has an entropy of 0, there is no ambiguity regarding the cluster to which a randomly chosen sample belongs, which is the case when there is only one cluster.

MI quantifies how much knowledge one clustering provides regarding the other. The degree to which knowing the cluster of a sample in $C$ decreases uncertainty regarding the cluster of the sample in $C’$ can be determined by MI.

Normalized mutual information is MI that has been normalized using the geometric or arithmetic mean of the clusterings’ entropies. Because standard MI is not limited by a constant value, normalized mutual information provides a more understandable clustering metric.

Another well-known metric in this category is variation of information (VI), which considers both the clustering entropy and MI. Let $H(C)$ represent the entropy of a clustering and $I(C, C’)$ represent the MI between two clusterings. The VI between two clusterings can be defined as $VI(C,C’) = H(C)+H(C’)-2I(C,C’)$. When the VI is 0, it means that the two clusterings are a perfect match.

Set Overlap

Finding the best match for clusters in $C$ with clusters in $C’$ based on the greatest overlap between the clusters is the goal of set overlap metrics. A value of 1 indicates that the clusterings are the same for all metrics in this category.

The confusion matrix is examined by the maximum matching measure in descending order, and the confusion matrix’s largest entry is matched first. It then removes the matched clusters and repeats the procedure until all of the clusters have been used.

The F-measure is another metric for determining set overlap. In contrast to the maximum matching measure, the F-measure is frequently employed to compare a clustering to an ideal solution rather than contrasting two clusterings.

Using the F-Measure to Apply Clustering Metrics

We’ll go over the F-measure in more detail with an example because it’s widely used in machine learning models and has significant uses in things like search engines.

Definition of F-measure

Let’s say $C$ is our ideal or ground truth solution. For any $k$th cluster in $C$, where $k \in [1, K]$, we’ll calculate an individual F-measure with every cluster in clustering result $C’$. This individual F-measure indicates how well the cluster $C^\prime_{k’}$ describes the cluster $C_k$ and can be determined through the precision and recall (two model evaluation metrics) for these clusters. Let’s say that $I_{kk’}$ represents the intersection of elements in the $k$th cluster of $C$ and the $k’$th cluster of $C’$, and that $\lvert C_k \rvert$ represents the number of elements in the $k$th cluster.

Precision $p = \frac{I_{kk’}}{\lvert C’_{k’} \rvert}$

Recall $r = \frac{I_{kk’}}{\lvert C_{k} \rvert}$

The individual F-measure of the $k$th and $k’$th clusters can then be determined as the harmonic mean of the precision and recall for those clusters:

[F_{kk’} = \frac{2rp}{r+p} = \frac{2I_{kk’}}{|C_k|+|C’_{k’}|}]

Let’s now examine the overall F-measure to compare $C$ and $C’$. First, we’ll build a matrix resembling a contingency table with each cell’s values representing the clusters’ individual F-measures. Let’s say that the rows of a table represent the clusters in $C$ and the columns represent the clusters in $C’$, with table values denoting specific F-measures. Locate the cluster pair with the highest individual F-measure, then delete the row and column that correspond to these clusters. Repeat this process until all clusters have been used. Finally, we are able to define the overall F-measure:

[F(C, C’) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^K n_imax(F(C_i, C’_j)) \forall j \in {1, K’}]

As you can see, the weighted sum of our highest individual F-measures for the clusters constitutes the overall F-measure.

Data Setup and Anticipated Results

Our environment will function with any Python notebook appropriate for machine learning, such as a Jupyter notebook. You might want to look over the README for my GitHub repository, the expanded readme_help_example.ipynb example file, and the requirements.txt file (which lists the required libraries) before we begin.

We will be using sample data from news articles that is available in the GitHub repository. Information such as category, headline, date, and short_description is organized in the data:

| category | headline | date | short_description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 49999 | THE WORLDPOST | Drug War Deaths Climb To 1,800 In Philippines | 2016-08-22 | In the last seven weeks alone. |

| 49966 | TASTE | Yes, You Can Make Real Cuban-Style Coffee At Home | 2016-08-22 | It’s all about the crema. |

| 49965 | STYLE | KFC’s Fried Chicken-Scented Sunscreen Will Kee… | 2016-08-22 | For when you want to make yourself smell finge… |

| 49964 | POLITICS | HUFFPOLLSTER: Democrats Have A Solid Chance Of… | 2016-08-22 | HuffPost’s poll-based model indicates Senate R… |

We can read, examine, and alter the data with the help of pandas. Because the entire dataset is so large, we’ll order the data by date and choose a small sample (10,000 news headlines) for our demonstration:

| |

The notebook should output the result 30 after running, indicating that this data sample contains 30 categories. You can also run df.head(4) to see the data’s storage format. (It ought to resemble the table in this section.)

Improving Clustering Features

Prior to applying clustering, we should preprocess the text to eliminate our model’s superfluous features, such as:

- Making the text’s case consistent.

- Taking out any special or numerical characters.

- Lemmatization.

- Eliminating stop words.

| |

The resulting preprocessed headlines are displayed as processed_input, which you can view by running df.head(4) once more:

| category | headline | date | short_description | processed_input | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 49999 | THE WORLDPOST | Drug War Deaths Climb To 1,800 In Philippines | 2016-08-22 | In the last seven weeks alone. | drug war deaths climb philippines |

| 49966 | TASTE | Yes, You Can Make Real Cuban-Style Coffee At Home | 2016-08-22 | It’s all about the crema. | yes make real cuban style coffee home |

| 49965 | STYLE | KFC’s Fried Chicken-Scented Sunscreen Will Kee… | 2016-08-22 | For when you want to make yourself smell finge… | kfc fry chicken scent sunscreen keep skin get … |

| 49964 | POLITICS | HUFFPOLLSTER: Democrats Have A Solid Chance Of… | 2016-08-22 | HuffPost’s poll-based model indicates Senate R… | huffpollster democrats solid chance retake senate |

We must now represent each headline as a numerical vector in order to apply any machine learning model to it. To do this, a variety of feature extraction methods are available. We’ll be employing TF-IDF (term frequency-inverse document frequency). Because these words shouldn’t be the deciding factor in clustering or classifying documents, this technique lessens the impact of frequently used words (in our example, news headlines).

| |

Next, we’ll test out our first clustering method, agglomerative clustering, on these feature vectors.

Method 1 for Clustering: Agglomerative Clustering

Let’s contrast the results of agglomerative clustering with the news categories we were given as the best solution (with the desired number of clusters set to 30 because there are 30 categories in the dataset):

| |

We will use integer labels to denote the clusters that are found; identical integer labels are applied to headlines that correspond to the same cluster. Using the cluster_measure function from the compare_clusters module of our GitHub repository, we can determine the aggregate F-measure and the number of perfectly matching clusters to gauge the precision of our clustering result:

| |

When we compare these cluster results to the best solution, we discover a low F-measure of 0.198 and no clusters that correspond to the headline categories we selected, indicating that the agglomerative clusters do not correspond to the headline categories we selected. Let’s examine a cluster from the outcome to understand its composition.

| |

When we examine the results, we discover that this cluster includes headlines from each category:

| |

Given that the clusters in our result do not correspond to the ideal solution, our low F-measure makes sense. It’s crucial to remember that the category classification we selected only represents one potential way to divide the dataset. A low F-measure in this instance does not mean that the clustering result is incorrect, but rather that it did not match our intended method of data partitioning.

Method 2 for Clustering: K-means

Let’s test a different well-liked clustering algorithm on the same dataset: k-means clustering. We will make a new dataframe and use the cluster_measure function once more:

| |

Our k-means clustering result, like the agglomerative clustering result, produced clusters that are not similar to our predetermined categories: When compared to the best solution, it has an F-measure of 0.18. It would be interesting to compare the two clustering results because their F-measures are so similar. We only need to determine the F-measure because we already have the clusterings. In order to begin, we’ll combine both results into a single column, with class_gt containing the agglomerative clustering output and class_prd containing the k-means clustering output:

| |

We can see that the clusterings generated by the two algorithms are more similar to one another than they are to the optimal solution because the F-measure is higher at 0.4.

Discover More for Improved Clustering Results

Your analysis of machine learning models will benefit from an understanding of the clustering comparison metrics that are available. We demonstrated the F-measure clustering metric in action and provided you with the fundamental knowledge you need to use these lessons in your subsequent clustering result. My top recommendations for further reading are listed below if you want to learn more:

- Comparing Clusterings - An Overview by Dorothea Wagner and Silke Wagner

- Comparing clusterings—an information based distance by Marina Meilă

- Information Theoretic Measures for Clusterings Comparison: Variants, Properties, Normalization and Correction for Chance by Nguyen Xuan Vinh, Julien Epps, and James Bailey

The Toptal Engineering Blog thanks Luis Bronchal for reviewing the code samples used in this article.