What unites major chipmakers like AMD, ARM, Samsung, MediaTek, Qualcomm, and Texas Instruments? Besides their shared focus on semiconductors, they are all founding members of the HSA Foundation. So, what exactly is HSA, and why does it require support from such industry giants?

This article aims to explain why HSA might become incredibly important in the near future. Let’s start with the basics: What is HSA, and why should it matter to you?

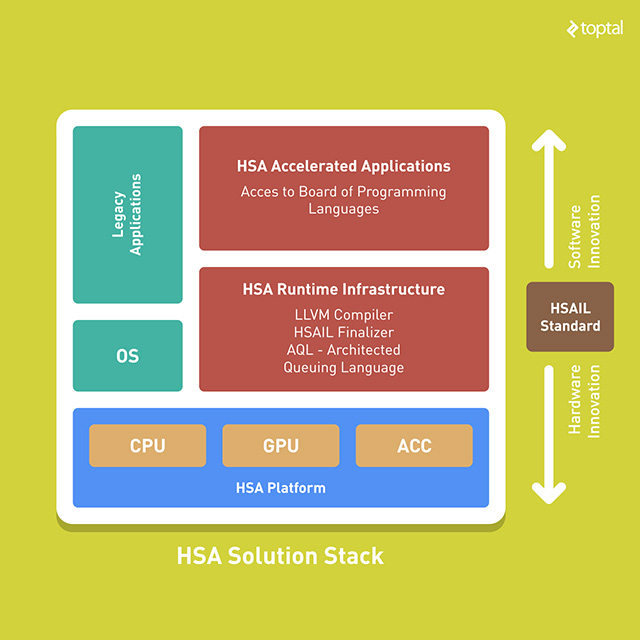

HSA, or Heterogeneous System Architecture, might sound a bit dull, but believe me, it has the potential to be revolutionary. Essentially, HSA is a collection of standards and specifications designed to enable closer integration of CPUs and GPUs on the same bus. This concept isn’t entirely new, as desktop CPUs and mobile SoCs have been using integrated graphics and shared buses for years. However, HSA elevates this to a whole new level.

HSA goes beyond just sharing the same bus and memory for the CPU and GPU; it allows these fundamentally different architectures to collaborate and divide tasks between them. This might not seem significant at first, but upon closer examination of its potential long-term implications, its technical brilliance becomes clear.

Another Technical Standard for Developers to Implement?

Well, yes and no.

Sharing the same bus isn’t a new concept, nor is using highly parallel GPUs for specific computing tasks (beyond just rendering graphics). These practices are already in place, and many readers are likely familiar with GPGPU standards like CUDA and OpenCL.

Unlike CUDA or OpenCL, however, HSA aims to remove the developer from the equation, at least when it comes to assigning workloads to specific processing cores. The hardware itself would decide when to shift calculations from the CPU to the GPU and vice versa. Importantly, HSA isn’t intended to replace existing GPGPU programming languages like OpenCL; these can still be implemented on HSA hardware.

HSA’s core purpose is to simplify this entire process, making it as seamless as possible. Developers wouldn’t necessarily need to consider offloading calculations to the GPU, as the hardware would handle it automatically.

For this to work, HSA needs broad support from various chipmakers and hardware manufacturers. Although the list of HSA supporters is impressive, one notable absence is Intel. Given Intel’s dominance in the desktop and server CPU markets, this is a significant factor. Another missing name is Nvidia, the current leader in the GPU compute market, which is heavily invested in CUDA.

It’s important to note that HSA isn’t designed exclusively for high-performance systems and applications typically associated with Intel. It can also be utilized in energy-efficient mobile devices, a market where Intel has minimal presence.

So, while HSA promises to simplify things, is it relevant yet? Will it gain widespread adoption? This isn’t just a technological question but an economic one, dependent on market forces. Let’s examine the current landscape and how we arrived here.

HSA Development: Challenges, Concerns, and Adoption

As mentioned earlier, HSA isn’t an entirely new idea. It was initially conceived by Advanced Micro Devices (AMD), a company with a strong interest in its success. A decade ago, AMD acquired graphics card manufacturer ATI, hoping to leverage ATI’s GPU technology to boost their overall sales.

The plan was seemingly straightforward: AMD would not only continue developing and manufacturing cutting-edge discrete GPUs, but also integrate ATI’s GPU technology into their processors. They dubbed this initiative ‘Fusion’, with HSA being referred to as Fusion System Architecture (FSA). It sounded promising, and in theory, offering a capable x86 processor with decent integrated graphics was a good idea.

Unfortunately, AMD encountered numerous obstacles, including:

- Competition from Intel, who quickly recognized the potential of the idea.

- Losing their technological advantage to Intel, making it increasingly difficult to compete in the CPU market due to Intel’s superior manufacturing technology.

- Execution challenges, resulting in delays and cancellations of new processors.

- The 2008 economic downturn and the subsequent rise of mobile devices, which significantly impacted the tech landscape.

These factors, among others, hampered AMD’s progress and hindered market adoption of their products and technologies. In mid-2011, AMD began releasing processors with their new generation of integrated Radeon graphics, branding them Accelerated Processing Units (APUs) instead of CPUs.

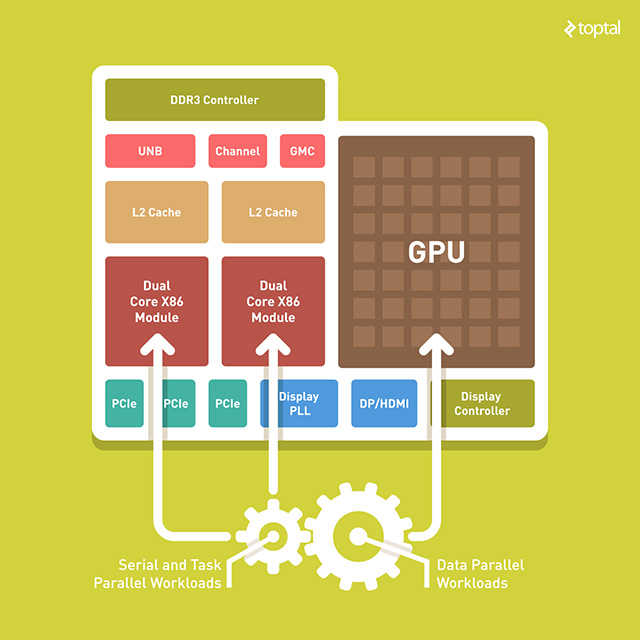

Marketing aside, AMD’s first-generation APUs (codenamed Llano) were a flop. They were delayed and couldn’t compete with Intel’s offerings. Significant HSA features were absent, but AMD started incorporating them in their 2012 platform (Trinity, essentially a refined Llano). 2014 saw the introduction of Kaveri APUs, which supported heterogeneous memory management (shared address space for GPU IOMMU and CPU MMU). Kaveri also brought about closer architectural integration, enabling coherent memory between the CPU and GPU (AMD calls this hUMA, short for Heterogeneous Unified Memory Access). The subsequent Carizzo refresh added even more HSA features, enabling the processor to context switch compute tasks on the GPU and perform other advanced operations.

AMD’s upcoming Zen CPU architecture, and the APUs built upon it, promise even more advancements, if and when they reach the market.

So, what’s the issue?

AMD wasn’t the only chipmaker to recognize the potential of on-die GPUs. Intel began incorporating them into their Core CPUs, as did ARM chipmakers. As a result, integrated GPUs are now found in virtually every smartphone SoC and the majority of PCs/Macs. Meanwhile, AMD’s position in the CPU market dwindled, making their platforms less attractive to developers, businesses, and consumers. There simply aren’t that many AMD-powered PCs out there, and Apple, a major player, doesn’t use AMD processors (though they have used AMD graphics, primarily for OpenCL compatibility).

AMD no longer competes with Intel in the high-end CPU market, and even if they did, it wouldn’t change much in this regard. People buying expensive workstations or gaming PCs don’t rely on integrated graphics; they opt for dedicated, high-performance graphics cards, prioritizing performance over energy efficiency.

HSA in Smartphones and Tablets?

But what about mobile platforms? Couldn’t AMD simply offer similar solutions for smartphones and tablets? Unfortunately, it’s not that simple.

Shortly after the ATI acquisition, AMD faced financial difficulties, worsened by the economic crisis. To mitigate this, they sold their Imageon mobile GPU division to Qualcomm. Qualcomm rebranded these products as Adreno (an anagram of Radeon) and became the dominant force in the smartphone processor market, utilizing their newly acquired GPU technology.

In retrospect, selling a smartphone graphics division just as the smartphone revolution was taking off might not seem like a wise business decision. However, hindsight is always 20/20.

Initially, HSA was associated solely with AMD and their x86 processors, but this is no longer the case. If all HSA Foundation members began shipping HSA-enabled ARM smartphone processors, they would vastly outsell AMD’s x86 processors in terms of both revenue and units shipped. What would happen if they did? How would it impact the industry and developers?

For starters, smartphone processors already leverage heterogeneous computing to some extent. Heterogeneous computing typically refers to utilizing different architectures within a single chip. Given the various components found in today’s highly integrated SoCs, this definition can be quite broad. Consequently, almost any SoC could be considered a heterogeneous computing platform, depending on the criteria used. Sometimes, even processors based on the same instruction set are referred to as a heterogeneous platform (for instance, mobile chips with both ARM Cortex-A57 and A53 cores, both based on the 64-bit ARMv8 instruction set).

Many experts agree that most ARM-based processors, including Apple’s A-series chips, Samsung’s Exynos SoCs, and processors from other major vendors like Qualcomm and MediaTek, can be considered heterogeneous platforms.

But why would anyone need HSA on smartphone processors? Isn’t the primary purpose of utilizing GPUs for general computing to handle demanding workloads, not mobile games and apps?

While true, it doesn’t mean a similar approach can’t be employed to enhance efficiency, a crucial aspect of mobile processor design. Instead of crunching massive parallel tasks on a high-end workstation, HSA could be used to make mobile processors more efficient and versatile.

Most people don’t scrutinize processor details; they typically glance at the spec sheet when purchasing a new phone and focus on the numbers and brand names. They rarely examine the SoC die itself, which reveals a lot. In high-end smartphone processors, GPUs often occupy more silicon real estate than CPUs. Since they’re already present, why not utilize them effectively for tasks beyond gaming?

A hypothetical, fully HSA-compliant smartphone processor could empower developers to harness this potential without significant cost increases, enabling them to implement more features and improve efficiency.

Theoretically, here’s how HSA could benefit smartphone processors:

- Enhanced efficiency by offloading suitable tasks to the GPU.

- Improved performance by offloading the CPU in certain scenarios.

- More effective utilization of the memory bus.

- Potential reduction in chip manufacturing costs by utilizing more silicon simultaneously.

- Introduction of new features that CPUs would struggle to handle efficiently.

- Simplified development through standardization.

This sounds promising, especially considering developers wouldn’t need to invest substantial effort in implementation. That’s the theory, but we need to see it in action, which might take some time.

How Does HSA Work?

I’ve already outlined the basics, but I’ll avoid delving into excessive detail for a couple of reasons: lengthy technical explanations can be tedious, and HSA implementations can vary.

Therefore, I’ll provide a concise overview of the concept.

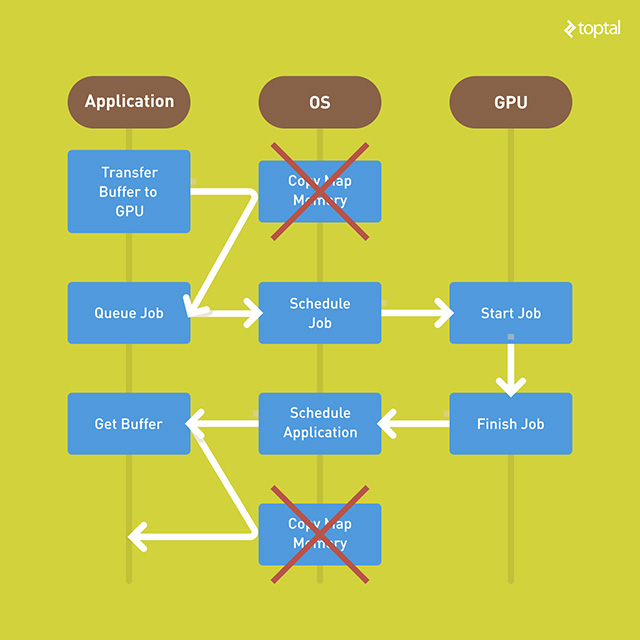

In a standard system, an application would offload calculations to the GPU by transferring data buffers to the GPU’s memory. This involves a CPU call followed by queuing. The CPU then schedules and dispatches the job to the GPU, which returns the processed data to the CPU upon completion. Finally, the application retrieves the buffer, which needs to be mapped by the CPU before it can be accessed. This approach involves a lot of back-and-forth communication.

In an HSA system, the application simply queues the job. The HSA-enabled CPU takes over, hands it off to the GPU, retrieves the results, and delivers them back to the application. It’s that simple.

This is achieved by allowing the CPU and GPU to directly share system memory, though other processing units could also be involved (e.g., DSPs). To enable this level of memory integration, HSA utilizes a virtual address space for compute devices. This means CPU and GPU cores can access memory on equal terms, provided they share page tables, allowing data exchange between different devices using pointers.

This significantly improves efficiency by eliminating the need to allocate separate memory to the GPU and CPU using virtual memory for each. Thanks to unified virtual memory, both can access system memory as needed, leading to better resource utilization and greater flexibility.

Imagine a low-power system with 4GB of RAM, where 512MB is typically allocated to the integrated GPU. This model lacks flexibility, as the amount of GPU memory is fixed. With HSA, this allocation becomes dynamic. If the GPU handles numerous tasks and requires more RAM, the system can provide it seamlessly. For instance, in graphics-intensive applications with high-resolution assets, the system could allocate 1GB or more RAM to the GPU on the fly.

In essence, HSA and non-HSA systems would share the same memory bandwidth and access the same amount of memory. However, the HSA system could utilize it far more efficiently, enhancing performance and reducing power consumption. It’s all about maximizing resource utilization.

What Can Heterogeneous Computing Do?

The straightforward answer is that heterogeneous computing, including HSA as one implementation, should be used for tasks better suited to GPUs than CPUs. But what does that actually mean? What are GPUs good at?

Modern integrated GPUs, while less powerful than discrete graphics cards (especially high-end gaming and workstation solutions), are significantly more potent than their predecessors.

You might assume integrated GPUs are still underwhelming, and for years, they were essentially just good enough for basic home and office PCs. However, this started changing around a decade ago as integrated GPUs moved from the chipset into the CPU package and die, becoming truly integrated.

While still significantly less powerful than flagship GPUs, integrated GPUs possess considerable potential. Like all GPUs, they excel at single instruction, multiple data (SIMD) and single instruction, multiple threads (SIMT) workloads. If you need to process large amounts of data in repetitive, parallel tasks, GPUs are ideal. CPUs, on the other hand, still outperform GPUs in complex, branching workloads.

This is why CPUs have fewer cores, typically between two and eight, optimized for sequential processing. GPUs, in contrast, can have hundreds or even thousands of smaller, more efficient cores in high-end discrete graphics cards. GPU cores are designed to handle multiple simple tasks concurrently, while CPUs are better suited for fewer, more complex tasks. Offloading these parallel tasks to the GPU can significantly improve efficiency and performance.

If GPUs are so well-suited for these tasks, why haven’t we been using them for general computing for years? The industry has tried, but progress was initially slow and limited to specific niches. This concept was initially called General Purpose Computing on Graphics Processing Units (GPGPU). Early attempts faced limitations, but the GPGPU concept was sound and eventually led to the development and standardization of Nvidia’s CUDA and Apple’s/Khronos Group’s OpenCL.

CUDA and OpenCL significantly advanced the field, enabling programmers to utilize GPUs in novel and more effective ways. However, they were vendor-specific. CUDA worked on Nvidia hardware, while OpenCL was initially limited to ATI hardware (and later embraced by Apple). Microsoft’s DirectCompute API, released with DirectX 11, offered a more limited, vendor-agnostic approach but was restricted to Windows.

Here’s a summary of some key GPU computing applications:

Traditional high-performance computing (HPC): HPC clusters, supercomputers, GPU clusters for compute workloads, GRID computing, load balancing.

Physics simulations: These can be related to gaming or graphics but also encompass fluid dynamics, statistical physics, and other complex calculations.

Geometry processing: This includes tasks like transparency computations, shadows, collision detection, and more.

Audio processing: Using GPUs instead of dedicated DSPs for tasks like audio effects, speech processing, and analog signal processing.

Digital image processing: This is what GPUs are designed for, so they excel at accelerating image and video post-processing and decoding. Even an entry-level GPU can outperform a CPU in tasks like decoding a video stream and applying a filter.

Scientific computing: This includes climate modeling, astrophysics, quantum mechanics, molecular modeling, and other computationally demanding scientific applications.

Other computationally intensive tasks: Encryption/decryption is one example. Whether it’s mining cryptocurrencies, encrypting sensitive data, cracking passwords, or detecting viruses, GPUs can significantly accelerate these processes.

This is not an exhaustive list, as GPU compute can be applied to a wide range of fields, including finance, medical imaging, database management, and statistics. You’re limited only by your imagination. “Computer vision” is another emerging application. Powerful GPUs are essential for training self-driving cars and drones to avoid obstacles and navigate their surroundings.

Feel free to insert your favorite driverless car joke here.

Developing for HSA: Not Quite There Yet

While potentially biased by my enthusiasm for GPU computing, I believe HSA holds immense promise, provided it’s implemented effectively and gains sufficient support from chipmakers and developers. However, progress has been slow, perhaps slower than I’d hoped. As someone who loves seeing new technology in action, I’m eager for it to gain traction.

The main challenge is that HSA isn’t quite there yet. While it might eventually take off, it could take a while. We’re not just talking about new software; HSA requires new hardware to fully realize its potential. Much of this hardware is still in development, though progress is being made.

This doesn’t mean developers aren’t working on HSA-related projects, but interest and progress remain limited. Here are some resources to explore if you’re interested in experimenting with HSA:

The HSA Foundation @ GitHub is the primary hub for HSA resources. The HSA Foundation hosts and maintains numerous projects on GitHub, including debuggers, compilers, essential HSAIL tools, and more. Most resources are currently geared towards AMD hardware.

The HSAIL resources provided by AMD provides a good overview of the HSAIL specification. HSAIL stands for HSA Intermediate Language, a crucial tool for compiler and library developers targeting HSA devices.

The HSA Programmer’s Reference Manual (PDF) contains the complete HSAIL specification along with a comprehensive explanation of the intermediate language.

While HSA Foundation resources are currently limited and their Developers Program is “coming soon,” there are several official developer tools available. These provide valuable insights into the necessary software stack for getting started.

The official AMD Blog also features some useful HSA content.

These resources should be enough to get you started if you’re curious. The question is whether it’s worth investing your time and effort right now.

The Future of HSA and GPU Computing

When discussing emerging technologies, we face a dilemma: encourage readers to dive in and explore or advise them to wait and see.

As mentioned, I’m personally invested in the concept of GPU computing. While most developers might not need it right now, it could become increasingly important in the future. Unfortunately for AMD, it’s unlikely to disrupt the x86 processor market significantly. However, it could play a more substantial role in ARM-based mobile processors. Despite being AMD’s brainchild, companies like Qualcomm and MediaTek are better positioned to bring HSA-enabled hardware to millions of users.

Success hinges on a perfect synergy between software and hardware. If mobile chipmakers embrace HSA, it could be a game-changer. A new generation of HSA chips would blur the line between CPU and GPU cores, sharing the same memory bus as equals. This could lead to a shift in how companies market these chips. For example, AMD already promotes its APUs as “compute devices” comprised of different “compute cores” (CPUs and GPUs).

Mobile chipmakers might adopt a similar approach. Instead of advertising a chip with eight CPU cores and a separate GPU, they could focus on clusters, modules, and units. A processor with four small and four large CPU cores could be marketed as a “dual-cluster” or “dual-module” design, or a “tri-cluster” or “quad-cluster” design if GPU cores are included. Many technical specifications become less meaningful over time, like the DPI of your printer or the megapixel count of a budget smartphone camera.

This shift goes beyond just marketing. If GPUs become as flexible as CPU cores, accessing system resources on equal terms, why even distinguish them by their traditional names? Two decades ago, dedicated mathematical coprocessors (FPUs) became integrated into CPUs, rendering them obsolete. Within a few product cycles, we forgot they ever existed.

It’s worth noting that HSA isn’t the only approach to leveraging GPUs for general-purpose computing.

Intel and Nvidia have chosen different paths. Intel has been quietly increasing its GPU R&D investment, and their latest integrated graphics solutions are quite capable. As on-die GPUs become more powerful and occupy more silicon real estate, Intel will need to find innovative ways to utilize them for general computing.

Nvidia, on the other hand, exited the integrated graphics market years ago (when they stopped producing PC chipsets) after a brief foray into the ARM processor market with their Tegra series. While not hugely successful, Tegra chips are still used in some devices, and Nvidia is now focusing on embedded systems, particularly automotive applications. In this context, integrated GPUs are crucial for tasks like collision detection, indoor navigation, 3D mapping, and more. Remember Google’s Project Tango? Some of its hardware relied on Tegra chips for depth sensing and other advanced features. On the opposite end of the spectrum, Nvidia’s Tesla product line dominates the high-end GPU compute market, solidifying their position in this niche for years to come.

In conclusion, while GPU computing shows immense promise, current technological limitations remain. HSA could address many of these challenges but faces hurdles due to limited industry-wide support.

It might take several years, but I’m optimistic that GPUs will eventually become integral to general computing, even in mobile devices. The technology is almost ready, and economic factors will drive adoption. Here’s a simple example: Intel’s current Atom processors feature 12 to 16 GPU Execution Units (EUs), a significant increase from the four EUs found in their predecessors. As integrated GPUs become larger, more powerful, and consume more die area, chipmakers will inevitably utilize them to improve overall performance and efficiency. Failing to do so would negatively impact profit margins and shareholder value.

Don’t worry, you’ll still be able to play games on these future GPUs. However, even when you’re not gaming, the GPU will be working behind the scenes, offloading the CPU to enhance performance and efficiency.

This would be a significant development, particularly for affordable mobile devices.