To reiterate, Python is a powerful, high-level programming language known for its dynamic typing and binding. Its clear syntax, well-organized modules and packages, and wide array of features make it a favorite among many developers.

Python doesn’t force you to use classes and objects. For simpler projects, you can work with functions or even write a basic script without any strict code structure. This makes Python program design very flexible and straightforward.

Despite this, Python is undeniably object-oriented. This is because, in essence, every element in Python is treated as an object. This includes functions, which are considered first-class objects (the meaning of which will be discussed later). Remember this important fact about functions being objects.

Therefore, you can write both simple scripts and intricate frameworks, applications, and libraries in Python. Its capabilities are vast, though naturally, there are limitations, which are beyond the scope of this article.

However, due to Python’s power and flexibility, certain rules or patterns are necessary for effective programming. Let’s explore these patterns and their relevance to Python, along with implementing a few essential ones.

Why Is Python Suitable For Patterns?

Every programming language can benefit from patterns. In reality, patterns should be viewed in the context of the specific language being used. Both patterns and the syntax and nature of a language (dynamic, functional, object-oriented, etc.) impose constraints on programming. These constraints, along with the reasons behind them, can differ significantly. The limitations imposed by patterns are deliberate and serve a purpose. That’s the fundamental goal of patterns: to guide us on how to approach a problem and what to avoid. More on patterns, especially Python design patterns, later.

Python’s core philosophy emphasizes well-defined best practices. Being a dynamic language (as mentioned before), it either inherently implements or simplifies the implementation of numerous popular design patterns with minimal code. Some are so ingrained that we use them unknowingly. Even a moderately experienced developer could easily spot them within existing Python code. Other patterns become redundant due to the nature of the language.

For instance, the Factory pattern, a structural pattern in Python, aims to create new objects while abstracting the instantiation logic from the user. However, Python’s dynamic object creation makes additions like Factory generally unnecessary. You’re still free to implement it, and there might be specific cases where it proves beneficial, but these are exceptions.

What makes Python’s philosophy so advantageous? Let’s examine this in the Python terminal:

| |

While these might not be traditional Python patterns, they represent rules that define a “Pythonic” approach to programming, emphasizing elegance and practicality.

We also have the PEP-8 style guide for code structure. It’s an essential tool (with some exceptions, as PEP-8 itself encourages:

“However, always prioritize consistency. Sometimes, the style guide might not be applicable. When in doubt, use your best judgment, look at other examples, and don’t hesitate to seek advice!”

Combine PEP-8 with The Zen of Python (PEP-20), and you have a strong foundation for writing readable and maintainable code. Incorporate design patterns, and you’re equipped to build any software system with consistency and adaptability.

Python Design Patterns

What Is A Design Pattern?

It all begins with the Gang of Four (GOF). A quick online search will provide information if you’re unfamiliar with the GOF.

Design patterns offer established solutions to common problems. Two key principles underpin the design patterns defined by the GOF:

- Program to an interface, not an implementation.

- Favor object composition over inheritance.

Let’s delve into these principles from a Python programmer’s perspective.

Program to an interface, not an implementation

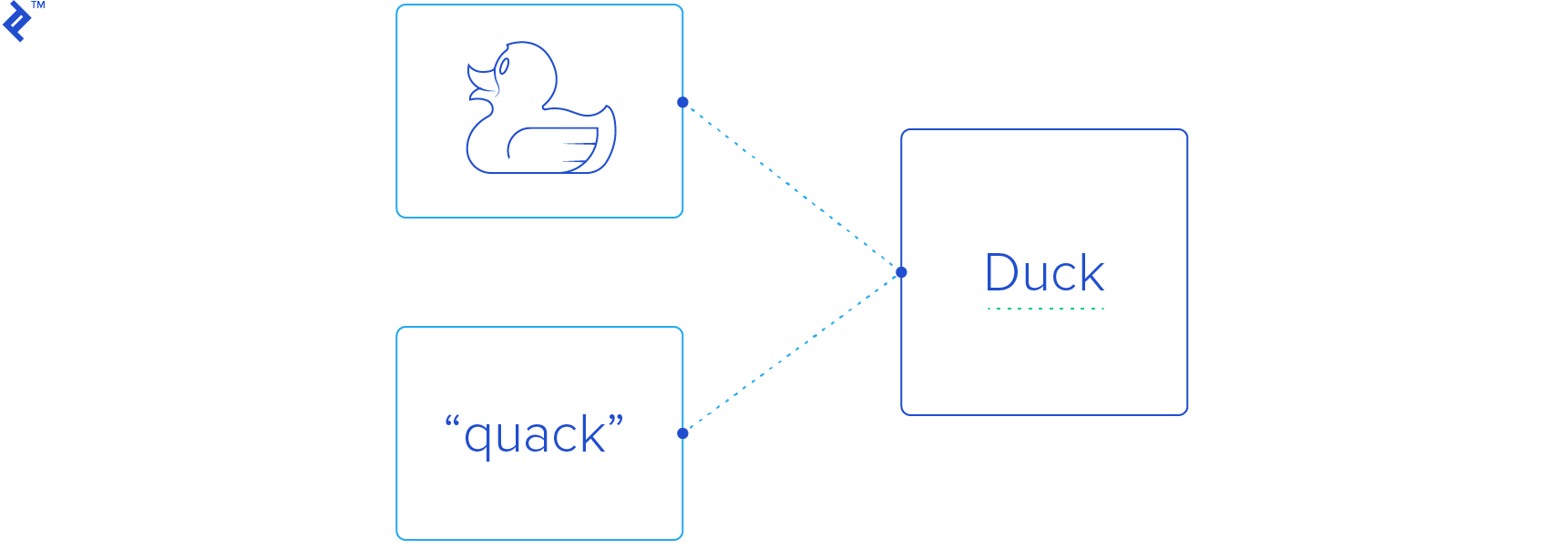

Consider Duck Typing. In Python, we tend not to explicitly define interfaces and program classes accordingly. However, this doesn’t mean we disregard interfaces altogether. In fact, we implicitly deal with them constantly through Duck Typing.

Let’s discuss Duck Typing to understand its role in this paradigm of programming to an interface.

The focus is not on the object’s inherent nature but on its ability to perform the required actions. We’re only concerned with its interface.

If it can quack like a duck, let it quack!

| |

Did we explicitly define an interface for our duck? No. Did we program to the interface instead of the implementation? Yes, and quite elegantly.

As Alex Martelli aptly puts it in his presentation on Python software design patterns, “Teaching ducks to type might take a while, but it saves you a lot of effort later!”

Favor object composition over inheritance

This principle truly embodies the “Pythonic” way. It’s more common to wrap classes within each other than to create complex class hierarchies.

Instead of doing this:

| |

We can do this:

| |

The benefits are clear. We can control which methods of the wrapped class are exposed. We can even inject the persister instance at runtime! For example, today it’s a relational database, tomorrow it could be something else entirely, as long as it provides the required interface (those ducks again).

Composition feels natural and elegant in Python.

Behavioral Patterns

Behavioral patterns deal with communication and interaction between objects to achieve a specific task. According to GOF principles, there are 11 behavioral patterns in Python: Chain of responsibility, Command, Interpreter, Iterator, Mediator, Memento, Observer, State, Strategy, Template, Visitor.

While I find these patterns incredibly useful, it doesn’t diminish the importance of other pattern groups.

Iterator

Iterators are fundamental to Python and contribute significantly to its power. Mastering Python iterators and generators equips you with a deep understanding of this particular pattern.

Chain of responsibility

This pattern provides a way to handle a request through a series of methods, each addressing a specific aspect. One crucial principle for clean code is Single Responsibility.

Every piece of code should have one, and only one, purpose.

This principle is deeply ingrained in the Chain of Responsibility pattern.

For instance, filtering content can be achieved using different filters, each designed for a precise type of filtering, such as offensive language, ads, or inappropriate content.

| |

Command

This was one of the first design patterns I implemented. It’s a reminder that patterns aren’t invented; they’re discovered. The Command pattern becomes particularly useful when we need to prepare an action in advance and execute it later. This encapsulation allows for adding features like undo/redo or maintaining an action history.

Here’s a simple, frequently used example:

| |

Creational Patterns

It’s worth noting that creational patterns are less prevalent in Python due to its dynamic nature.

Some argue that Factory is inherently built into Python. The language provides the flexibility to create objects elegantly, often negating the need for patterns like Singleton or Factory.

A Python Design Patterns tutorial I came across described creational patterns as providing “a way to create objects while hiding the creation logic, rather than instantiating objects directly using a new operator.”

This highlights the key difference: We don’t have a new operator in Python!

However, let’s see how to implement a few, just in case they offer any specific advantages.

Singleton

Singleton ensures only one instance of a class exists during runtime. Is it truly necessary in Python? In my experience, it’s simpler to create one instance explicitly and use it instead of implementing the Singleton pattern.

However, if you must implement it, you can leverage Python’s ability to modify the instantiation process using the __new__() method:

| |

In this example, Logger is a Singleton.

Here are some alternatives to using Singleton in Python:

- Use a module.

- Create a single instance at the top level of your application (e.g., in a config file).

- Pass the instance to every object that requires it (dependency injection).

Dependency Injection

Whether dependency injection is a design pattern is debatable, but it’s undoubtedly a powerful mechanism for achieving loose coupling, leading to more maintainable and extendable applications. Combine it with Duck Typing, and you have a winning combination.

I’ve included it in the creational patterns section because it deals with where and when objects are created – or rather, where they are not created. With dependency injection, objects are created externally and provided to the code that needs them, rather than being created directly within that code.

Consider this simple example of dependency injection:

| |

We inject the authenticator and authorizer methods into the Command class. The Command class simply needs to execute them without worrying about their implementation. This allows us to use the Command class with various authentication and authorization mechanisms at runtime.

We demonstrated injection through the constructor, but we can also inject dependencies by directly setting object properties:

| |

Dependency injection is a vast topic; exploring concepts like Inversion of Control (IoC) is highly recommended.

Before you do, though, take a look at another insightful Stack Overflow answer, the most upvoted one to this question.

Again, this showcases how implementing such a valuable design pattern in Python often boils down to utilizing the language’s built-in features.

The beauty of dependency injection lies in its facilitation of flexible and straightforward unit testing. Imagine an architecture where data storage can be switched on-the-fly. Mocking a database becomes incredibly easy. You can find more information in Toptal’s Introduction to Mocking in Python.

You might also want to research the Prototype, Builder, and Factory design patterns.

Structural Patterns

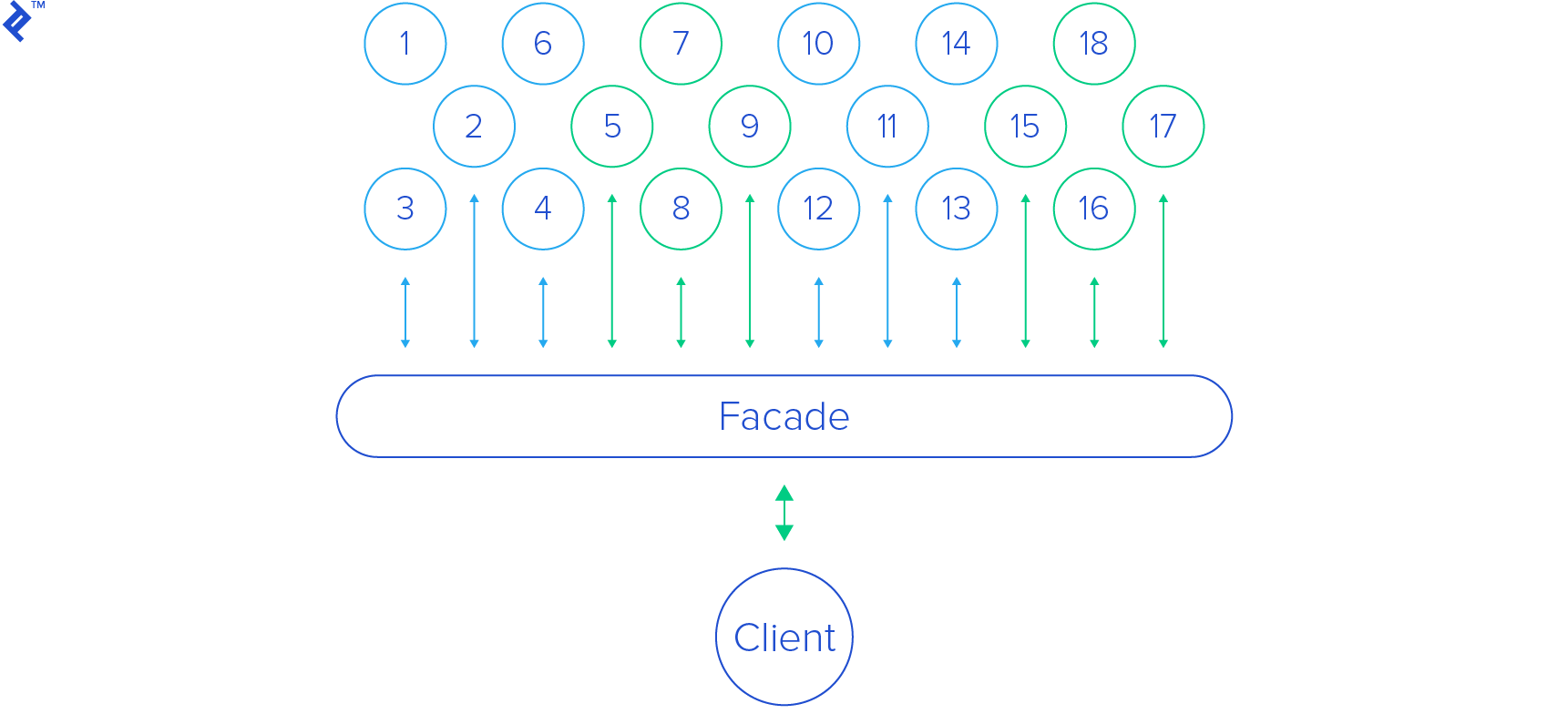

Facade

This could be the most well-known Python design pattern.

Imagine a system with numerous objects, each offering a wide array of API methods. While powerful, such a system can be complex to use. This is where the Facade pattern comes in. It involves creating a simplified interface object that exposes a well-defined subset of these API methods.

Here’s a Python Facade design pattern example:

| |

No surprises, no magic. The Car class acts as a Facade.

Adapter

While Facades simplify interfaces, Adapters modify them, much like using a cow when the system expects a duck.

Let’s say you have a method for logging information to a specific destination. Your method expects the destination to have a write() method (like a file object).

| |

This is a well-written method with dependency injection, allowing for great extensibility. However, what if you want to log to a UDP socket instead of a file? The socket object lacks a write() method. This is where you need an Adapter.

| |

The power of the adapter pattern shines when combined with dependency injection. Instead of modifying existing code to support new interfaces, you can simply create an adapter to translate the new interface to the familiar one.

You should also familiarize yourself with the bridge and proxy design patterns due to their similarities to adapter. Think about how easily they can be implemented in Python and their potential applications in your projects.

Decorator

Fortunately for us, Decorators are already integrated into Python. What I appreciate most about Python is its emphasis on best practices. While we still need to be mindful of them (including design patterns), Python naturally guides us towards them. Its best practices are intuitive, making it a joy for both novice and experienced developers.

The decorator pattern introduces additional functionality without relying on inheritance.

Let’s see how to decorate a method without using Python’s built-in decorator syntax. Here’s a straightforward example:

| |

The problem here is that the execute function handles more than just execution, violating the single responsibility principle.

It would be cleaner to have:

| |

We can move the authentication and authorization functionality to a separate decorator:

| |

Now, the execute() method is:

- Easy to read

- Focused on a single task

- Decorated with authentication

- Decorated with authorization

We can achieve the same result using Python’s integrated decorator syntax:

| |

Importantly, decorators aren’t limited to functions. They can involve entire classes as long as they are callable (by defining the __call__(self) method).

Exploring Python’s functools module is highly recommended for further exploration of decorators.

Conclusion

We’ve seen how naturally and easily design patterns can be implemented in Python. But more importantly, we’ve seen that programming in Python should be enjoyable.

“Simple is better than complex,” remember? You might have noticed that none of the design patterns were described in a rigid, overly formal way. No complex, full-blown implementations were provided. The key is to understand the essence of each pattern and implement it in a way that suits your coding style and the specific needs of your project.

Python is a powerful language that empowers you to write flexible and reusable code.

However, it also gives you the “freedom” to write really bad code. Avoid that! Embrace the Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY) principle, keep your lines of code under 80 characters, and incorporate design patterns where appropriate. It’s a fantastic way to learn from the collective experience of other developers and improve your code.