With the introduction of tools like Docker, Linux Containers, and others, creating isolated Linux system environments for individual processes has become incredibly easy. This eliminates the need for virtual machines, allowing a wide range of applications to coexist on a single Linux machine without interference. These tools have significantly benefited PaaS providers. But how do they achieve this?

These tools leverage various Linux kernel features and components, some relatively new and others requiring kernel patches. One crucial component, Linux namespaces, has existed since Linux version 2.6.24, released in 2008.

This article covers the fundamentals of Linux namespaces: their purpose, creation, and use. If you’re familiar with chroot, you already grasp the basic concept. Just as chroot makes any directory appear as the root filesystem to a process, Linux namespaces allow independent modification of other operating system aspects, such as process trees, network interfaces, mount points, and inter-process communication resources.

Why Use Linux Namespaces for Process Isolation?

Why use namespaces in Linux? On a single-user system, a single system environment might suffice. However, on servers running multiple services, isolating these services is crucial for security and stability. Imagine a server with multiple services, one of which is compromised. Without isolation, the intruder could potentially exploit the compromised service to gain access to others, even compromising the entire server. Namespace isolation mitigates this risk by providing a secure environment.

For instance, namespacing enables the safe execution of untrusted or unknown programs on servers. Online programming platforms like HackerRank, TopCoder, Codeforces, and others, as well as continuous integration services like Drone.io, rely on automated pipelines to run and validate user-submitted code, which may contain malicious elements. Running these programs in isolated namespaces safeguards the rest of the system from potential harm.

Namespacing tools like Docker offer fine-grained control over resource usage, making them popular among PaaS providers such as Heroku and Google App Engine. By isolating web applications within containers, these providers ensure that one application’s resource consumption or potential conflicts don’t impact others on the same hardware. This isolation even allows for different dependency software stacks and versions for each environment.

Docker’s ability to isolate processes in lightweight “containers” is similar to virtual machines but with less overhead. Virtual machines emulate hardware and run a separate operating system, providing complete isolation. Docker containers achieve comparable isolation using namespaces and other kernel features without the need for hardware emulation or a separate operating system, making them significantly more lightweight.

Process Namespace

Traditionally, Linux maintained a single process tree, a parent-child hierarchy representing all running processes. With sufficient privileges and conditions met, processes could inspect or even terminate others.

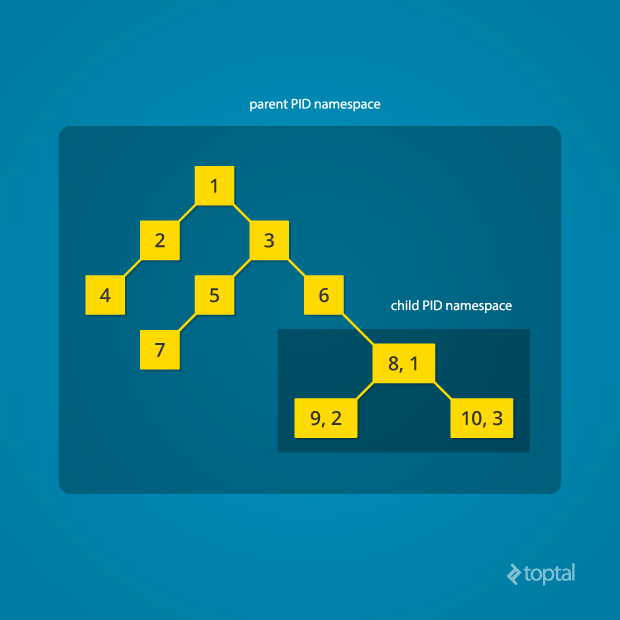

Linux namespaces introduced “nested” process trees, each with its own isolated set of processes. Processes in one tree cannot view, terminate, or even be aware of those in sibling or parent trees.

Upon booting, Linux starts with a single process (PID 1), the root of the process tree. It initiates other processes and services. The PID namespace allows creating new trees, each with its own PID 1 process. The creating process remains in the parent namespace but designates the child as the root of its own tree.

PID namespace isolation hides the parent process from the child namespace, while the parent retains full visibility into the child namespace.

Creating nested child namespaces is possible, with each child spawning its own isolated process tree.

PID namespaces allow a single process to have multiple PIDs, one for each namespace it belongs to. In the Linux kernel, we can see the pid struct, which previously tracked a single PID, now manages multiple PIDs using the upid struct:

| |

Creating a new PID namespace requires calling the clone() system call with the CLONE_NEWPID flag (accessible through wrappers in C and other languages). Unlike other namespaces, a PID namespace can only be created when spawning a new process using clone(). The new process immediately runs in the new PID namespace under a new process tree. Here’s a simple demonstration in C:

| |

Running this program with root privileges produces output similar to:

| |

The PID within child_fn will be 1.

Despite its simplicity, this code accomplishes a lot. clone() creates a new process, cloning the current one, and begins execution at child_fn(). However, it also detaches the new process from the original process tree, creating a separate tree for it.

Modify the child_fn() function to print the parent PID from the isolated process’s perspective:

| |

Running the modified program shows:

| |

The parent PID is 0, indicating no parent from the isolated process’s view. Removing the CLONE_NEWPID flag from the clone() call:

| |

Results in a non-zero parent PID:

| |

This is merely the first step. These processes still share access to resources like networking interfaces. For instance, the child process listening on port 80 would prevent other processes from doing the same.

Linux Network Namespace

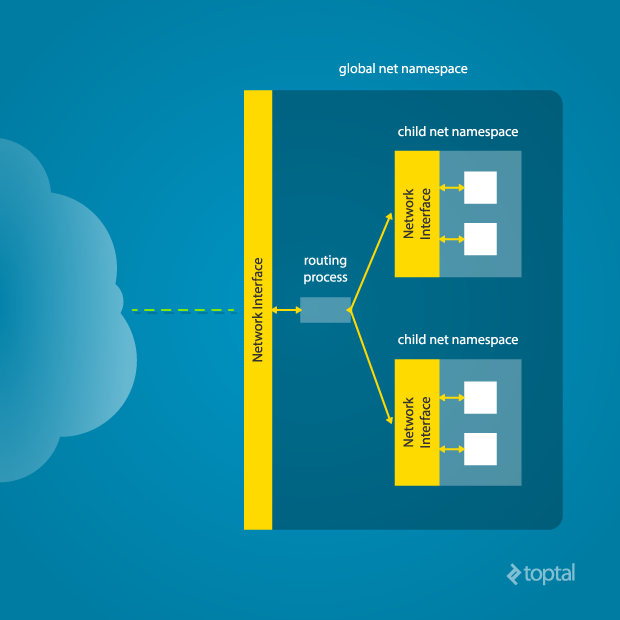

Network namespaces address this by providing each process with its own set of network interfaces, including separate loopback interfaces.

To isolate a process in its own network namespace, add the CLONE_NEWNET flag to the clone() call:

| |

Output:

| |

The physical interface enp4s0 resides in the global network namespace, while it’s absent in the child namespace. The loopback device is active globally but “down” in the child namespace.

To establish connectivity, create virtual network interfaces spanning namespaces. You can then create Ethernet bridges and route packets between them. A “routing process” in the global namespace directs traffic from the physical interface to the appropriate child namespaces through these virtual interfaces. Tools like Docker automate this complex process.

To manually connect a parent and child namespace, run this command from the parent namespace:

| |

Replace <pid> with the child process’s PID from the parent’s perspective. This creates a virtual Ethernet connection, with veth0 in the parent namespace and veth1 in the child namespace, simulating a physical connection. Assign IP addresses to both ends.

Mount Namespace

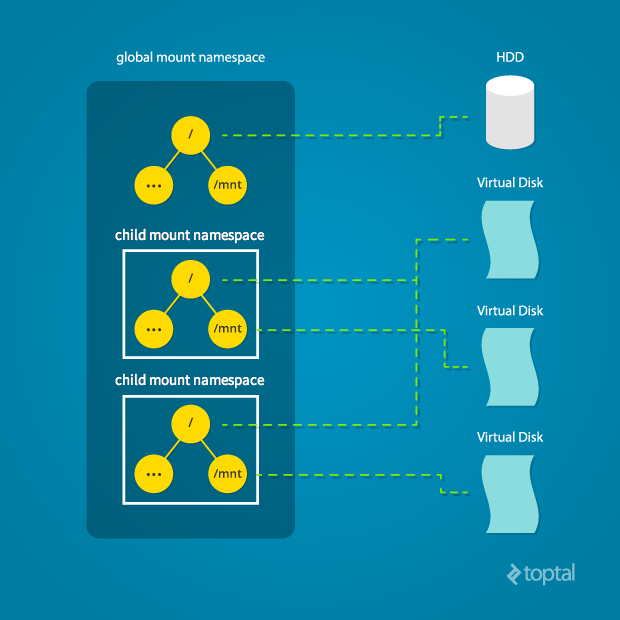

Linux maintains a data structure representing the system’s mount points, including mounted partitions, mount locations, and read-only status. Namespaces allow cloning this structure, enabling independent mount point manipulation without affecting other namespaces.

Creating a separate mount namespace is akin to chroot() but provides complete isolation beyond the root mountpoint. Each isolated process perceives its own view of the entire system’s mountpoint structure. This enables separate root filesystems and process-specific mountpoints, enhancing isolation and security.

Use the CLONE_NEWNS flag to achieve this:

| |

Initially, the child process inherits its parent’s mountpoints. However, it can freely mount and unmount endpoints within its own namespace without impacting others. While the child might initially share its parent’s root partition, it can later switch to a different one, affecting only its own namespace.

Spawning the target process directly with CLONE_NEWNS isn’t ideal. A better approach involves starting an “init” process with CLONE_NEWNS, modifying mountpoints as needed ("/", “/proc”, “/dev”, etc.), and then launching the target process. This is elaborated upon later in this tutorial.

Other Namespaces

Other namespaces include user, IPC, and UTS. The user namespace allows processes to have root privileges within the namespace without affecting the outside. IPC namespace isolation provides processes with their own interprocess communication resources, such as System V IPC and POSIX messages. The UTS namespace isolates the system’s nodename and domainname.

Here’s an example demonstrating UTS namespace isolation:

| |

Output:

| |

child_fn() prints, modifies, and reprints the nodename, demonstrating that the change is localized to the new UTS namespace.

For more information about namespaces and their functionalities, refer to here

Cross-Namespace Communication

Communication between parent and child namespaces is often necessary, whether for configuration, monitoring, or other purposes. While running a separate SSH daemon within each namespace is possible, it consumes significant resources. This is where the “init” process mentioned earlier proves beneficial.

The “init” process can establish a communication channel (e.g., UNIX sockets, TCP) between the namespaces. Creating a UNIX socket spanning namespaces involves creating the child process, then the socket, and finally isolating the child in a new mount namespace. Linux provides unshare(), allowing a process to isolate itself instead of being isolated by its parent. For example, this code achieves the same result as the network namespace example:

| |

This approach allows the “init” process to perform necessary setup tasks before isolating itself and executing the target child.

Conclusion

This tutorial provides a high-level overview of Linux namespaces and their use in process isolation. While tools like Docker and Linux Containers offer convenient abstractions, understanding the underlying mechanisms can be beneficial, especially when customized isolation is required.

This article only scratches the surface. There are more advanced concepts and techniques for enhancing process isolation and security in Linux. Nevertheless, this should serve as a solid starting point for those interested in the intricacies of namespace isolation.