Working in software development offers the flexibility to work across various industries, especially as a consultant. This is because a majority of software development skills are transferable across industries, companies, and projects. These transferable skills include areas like database design, design patterns, GUI layouts, and event management. However, there are also aspects specific to particular industries, companies, or projects.

The Role of Subject Matter Experts in Software Development

This is where a Subject Matter Expert (SME) becomes crucial, especially during the design phase of a project. SMEs possess extensive industry experience, understand industry-specific terminology, and comprehend the business logic driving the coding. While some technical understanding of software development can be beneficial for an SME, it isn’t mandatory for project success.

In many projects, a successful software application relies heavily on the developer understanding the business logic, which is where knowledge transfer from the SME becomes essential. The complexity of the project dictates the extent of knowledge transfer required.

Agile methodologies, which emphasize continuous collaboration, are particularly well-suited for this knowledge transfer process. Having one or more SMEs available throughout the development phases ensures ongoing knowledge transfer.

Challenges of Complete Knowledge Transfer

Depending on the industry and project scope, complete knowledge transfer from an SME might be impractical. For instance, expecting a physician with 25 years of experience or a biologist with 40 years of experience to transfer their vast knowledge within a typical software development timeframe of, say, 6 months, is unrealistic.

Furthermore, business rules within certain industries can be highly dynamic, changing more frequently than the typical software release cycle allows. In such scenarios, relying solely on frequent software releases to accommodate these changes may be impractical. This is where externalizing business rules using a business rules engine can be advantageous, enabling software to adapt to changes more readily and ensuring its long-term success.

When Business Rules Engines Are Beneficial

While many software projects allow for complete knowledge transfer and coding business logic directly into the application (using languages like C# or Java), certain projects are better suited for a different approach. These are projects with extensive and complex subject matter or highly volatile business rules. In such cases, allowing non-programmers (SMEs) direct access to manage business logic through a business rules engine becomes more effective.

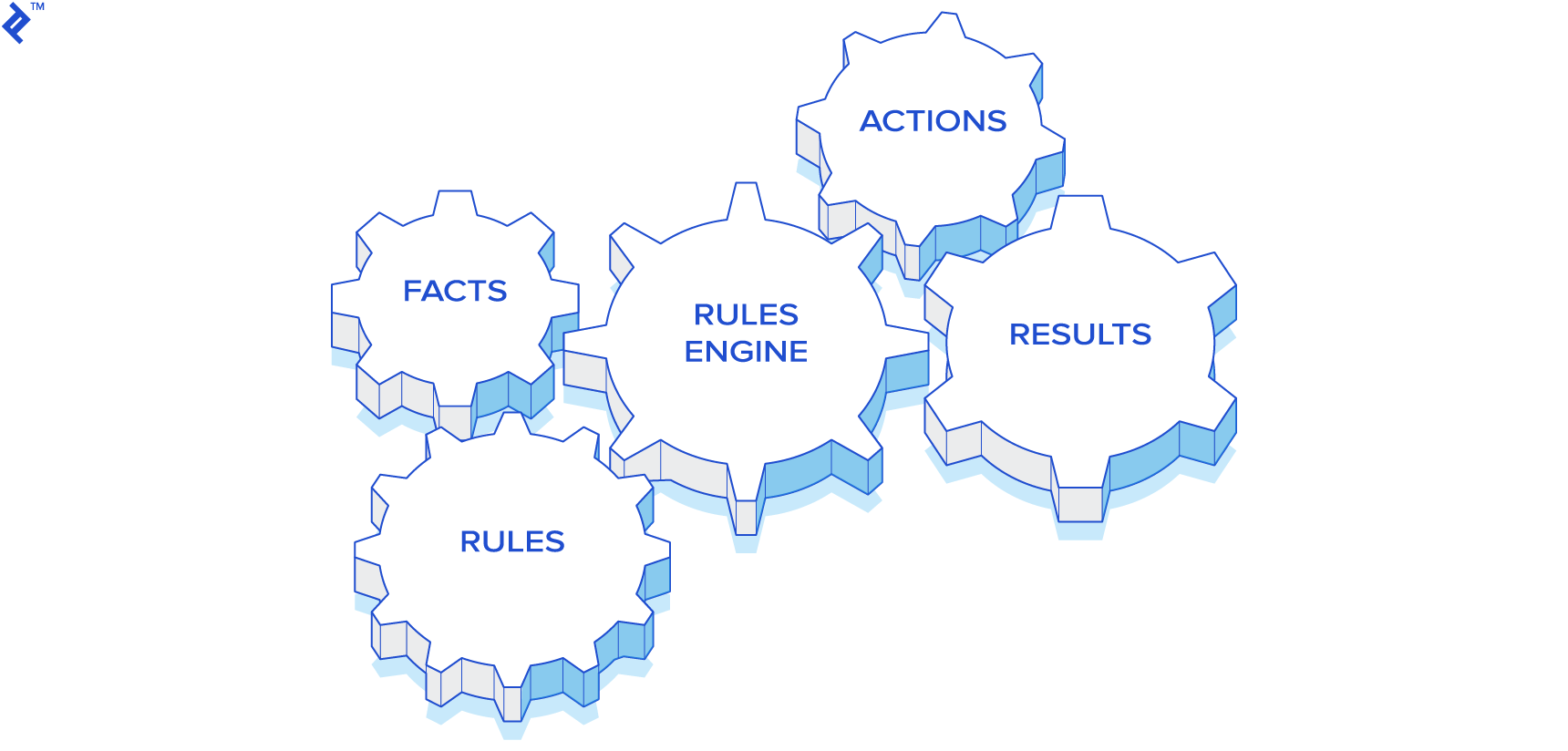

Understanding Business Rules Engines

A business rules engine is a tool designed to execute business rules. These rules consist of facts and conditional statements, essentially “if-then” statements commonly found in traditional business logic.

Let’s illustrate this with some examples: if an employee is absent for over 5 days without a doctor’s note, then a disciplinary action is required. If a business associate hasn’t been contacted in over 6 months and hasn’t made any purchases, then a follow-up email could be sent. If a patient presents with a high temperature, vision problems, and a family history of glaucoma, then further testing like an MRI might be necessary.

How SMEs Interact with Business Rules

Instead of requiring SMEs to learn complex programming languages, a simplified “mini-language” is created for them to express business rules. This language revolves around querying available facts relevant to their domain.

For example, facts in Human Resources could be salary, position, manager, or years with the company. In the medical field, facts could include temperature, blood pressure, or current medication. For finance, facts might be the current stock price, 52-week high/low, P/E ratio, or upcoming earnings dates. Essentially, the SME needs streamlined access to the information required for making business decisions.

The Structure of Business Rules

For this illustration, we’ll use Drools, an open-source, Java-based business rules engine. In Drools, rules are written in Java code and follow this basic structure:

Import statements go here:

| |

Working Memory in Drools

Drools utilizes a concept called Working Memory. Application code loads relevant facts into this Working Memory, enabling SMEs to write rules that query these facts. To maintain optimal performance, only facts pertinent to the application’s business logic should be loaded, avoiding irrelevant data.

For instance, when determining loan approval, relevant facts would include salary, credit scores, and existing loans. Factors like the day of the week or gender would be irrelevant.

Evaluating Rules in Drools

Once the Drools Working Memory contains both rules and facts, the rules are evaluated. This evaluation focuses on the “then” part of each rule. If the “then” condition is true, the “when” part of the rule is executed.

Typically, all rules are evaluated concurrently. However, grouping rules for evaluation on a per-group basis is also possible. Actions performed in the “then” part of a rule can modify the Working Memory, prompting Drools to re-evaluate all rules. If any re-evaluated rules now evaluate to true, their corresponding “when” parts are executed. This recursive evaluation process necessitates careful rule design.

Defining the “If” Side of a Rule in Drools

In Drools, facts are represented as objects. Rules can query for the presence or absence of specific object types, as well as the values of their attributes.

Here are a few examples:

Checking if an employee’s earnings exceed $100,000:

| |

Checking if a patient’s cholesterol is above 200 and if they are prescribed Lipitor:

| |

Checking if a stock’s price is within 1% of its yearly high:

| |

Combining Queries for Complex Logic

Drools allows combining multiple queries using Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) and parentheses for nesting, enabling complex business logic.

For example, to check if any manager earns below $75,000 or any director earns below $100,000:

| |

Querying Across Multiple Object Types

While previous examples focused on single object types, Drools allows queries spanning multiple object types.

For example, to determine if a customer’s salary is above $50,000 and they haven’t filed for bankruptcy:

| |

Defining Actions in the “Then” Side of a Rule

The “then” part of a rule dictates the actions taken when the “when” condition is met. In Drools, this can be any valid Java code.

However, for better rule reusability, it’s recommended to avoid including I/O operations, flow control, or general execution code within a rule. Instead, use the “then” part to modify the Working Memory, such as inserting a fact when a rule evaluates to true.

For example:

| |

Identifying Rule Evaluation Results

After all rules have fired, applications often need to know which rules evaluated to true. If rules add objects to the Working Memory upon evaluating to true, code can be written to check for the presence of these objects.

Referring to the previous example, after all rules have executed, the application can check if a LoanApproval() object exists in the Working Memory.

| |

Integrating a Business Rules Engine into Applications

Traditional applications typically combine business logic, GUI elements, I/O operations, and flow control code. Here’s a simplified example of how an application might process a user request:

| |

Introducing a rules engine adds a few steps to this process:

| |

SME Interaction: Creating, Editing, and Deleting Rules

A user-friendly GUI is essential for SMEs to effectively manage rules. Some business rules engines come bundled with such interfaces. For instance, Drools provides two user-friendly GUIs. The first resembles a spreadsheet, enabling rule creation without coding. The second GUI caters to more complex business logic.

While these GUIs are useful for simpler conditions, as logic complexity increases, custom GUI development might be necessary.

Key Features of a Custom SME GUI

For optimal SME productivity, consider these features in a custom GUI:

- Syntax Checker: A button to validate rule syntax by invoking Drools code and highlighting potential errors with line numbers.

- Drag/Drop Functionality: Simplify rule creation by providing SMEs with picklists to drag and drop objects and attributes, eliminating the need for memorization.

- Web Interface: Employing a thin client web interface ensures accessibility for SMEs without distribution concerns and simplifies GUI enhancements and maintenance.

- Rule Tester: Enhance SME productivity by enabling isolated testing of individual rules without relying on the entire application. Allow the GUI to define facts and execute specific rules.

Rule Storage Options

Drools offers two primary rule storage methods. By default, it works with file-based rules (typically with a .drl extension). This approach is suitable for smaller rule sets. For larger and more complex rule sets, database storage is preferable. While requiring more effort to implement, database storage offers better scalability and maintainability as the number of rules increases.

This overview covers only a fraction of the Drools Rules Language. For a comprehensive understanding, refer to the official reference documentation.

The decision to implement a rules engine should be weighed carefully. While offering greater flexibility and empowering SMEs, it also adds complexity to development, testing, and deployment. For further considerations, you might want to review the following guidelines.

Let’s move on to a practical example of Drools in a scenario familiar to many Toptal blog readers.

A Real-World Drools Example: Applicant Tracking

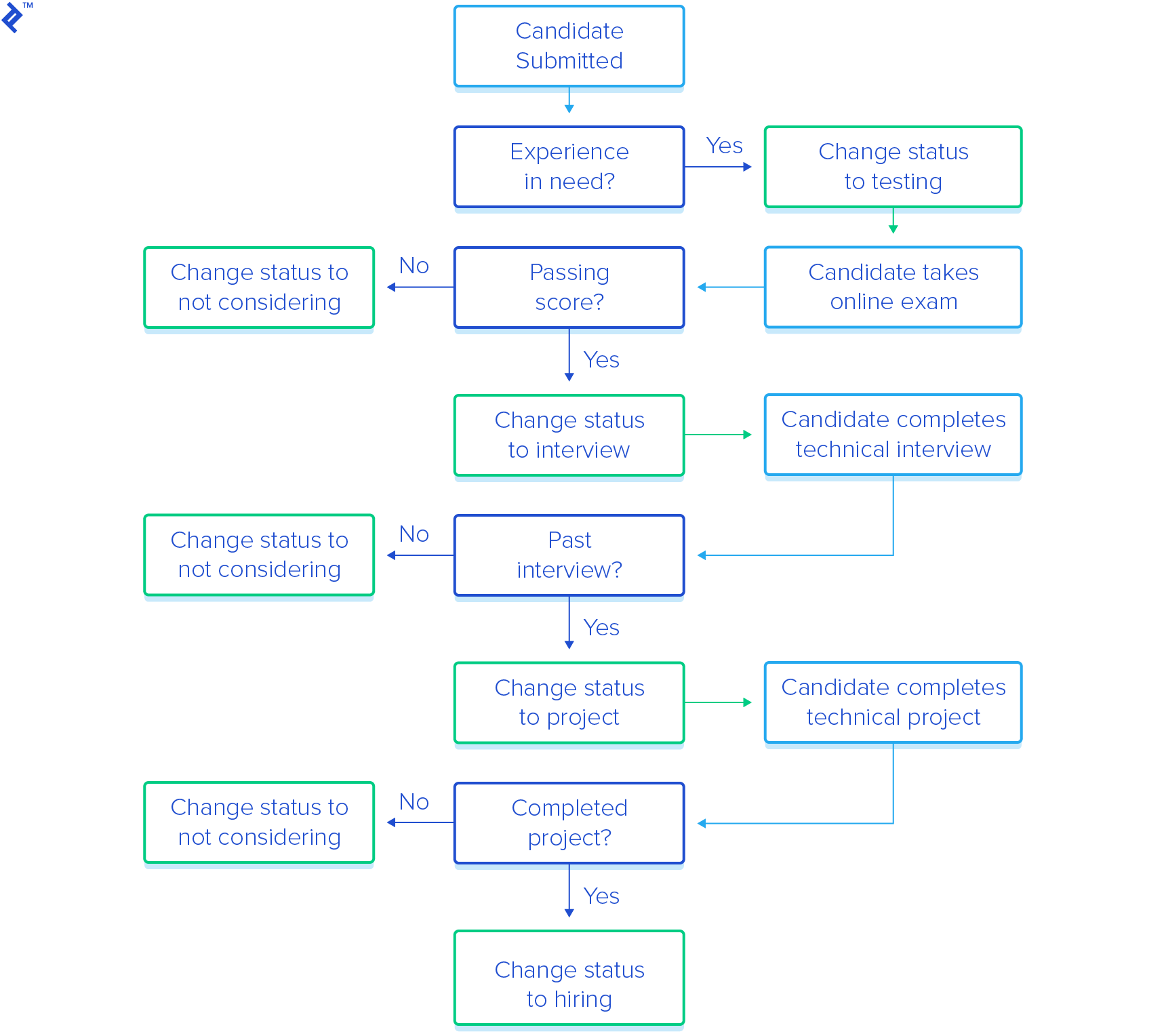

Toptal, a prominent platform for connecting businesses with top software developers, utilizes Applicant Tracking software to manage the various stages of its hiring process. Here’s a simplified visual representation:

Currently, the logic determining an applicant’s progression through the hiring stages is hardcoded, requiring IT involvement for any modifications. Toptal aims to empower Human Resources (HR) to directly manage these rules.

The proposed solution involves integrating a rules engine into the Applicant Tracking software. This enables HR-defined rules to be executed at each decision point in the hiring process. HR will work with a “Candidate” object representing an applicant, with fields for experience, test scores, interview scores, and other relevant data.

This simplified example showcases four interconnected rules:

- Submitted -> Testing

- Testing -> Interview

- Interview -> Project

- Project -> Hiring

Rule 1: Submitted -> Testing

HR wants a rule to determine whether a candidate should proceed to online testing based on current client requirements.

| |

Rule 2: Testing -> Interview

After the online exam, which assesses software development theory, problem-solving, and syntax, HR needs to evaluate candidate scores. This rule allows HR to define the score thresholds for advancing to a technical interview.

| |

Rule 3: Interview -> Project

Technical interviews evaluate a candidate’s experience, problem-solving skills, and communication abilities. HR defines the passing criteria for this stage.

| |

Rule 4: Project -> Hiring

Candidates passing the technical interview receive an offline programming project. The project submission is then assessed for completeness, architecture, and GUI design.

| |

This basic example highlights the potential of a rules engine in streamlining operations and empowering HR. The ability for HR to modify rules directly, without IT intervention, saves time and accelerates the candidate screening process.

Dynamic rule changes provide HR with greater flexibility. If there’s an overwhelming number of qualified candidates, criteria can be instantly adjusted. Conversely, if there’s a shortage, requirements can be relaxed to focus on the most critical skills.