This article builds on the first in our REST API series, where we set up a back-end project using npm, TypeScript, the debug module, Express.js, and Winston logging. If you’re comfortable with those concepts, you can clone the project repository (this), check out the toptal-article-01 branch using git checkout, and continue reading.

REST API Services, Middleware, Controllers, and Models

This article dives deeper into these modules:

- Services: These functions encapsulate business logic, making code cleaner and easier for middleware and controllers to utilize.

- Middleware: These functions validate requests before they reach the appropriate controller, ensuring prerequisites are met.

- Controllers: Using services, controllers process requests and formulate responses to send back to the requester.

- Models: These define the structure of our data and assist with compile-time type checking.

This part also introduces a simplified, temporary database unsuitable for production. It exists solely to illustrate concepts and prepare for a later article focusing on MongoDB and Mongoose integration.

Hands-on: First Steps with DAOs, DTOs, and Our Temporary Database

Instead of persistent storage, this tutorial’s database will temporarily hold user data in an array, meaning data is lost when Node.js exits. It only supports fundamental create, read, update, and delete (CRUD) operations.

Two key concepts we’ll use are:

- Data access objects (DAOs)

- Data transfer objects (DTOs)

Despite the subtle difference in acronyms, their roles are distinct: DAOs handle database interactions (CRUD), while DTOs hold the data exchanged between the DAO and the database.

Essentially, DTOs are objects adhering to data model types, and DAOs are the services that utilize them.

While DTOs can become more complex (e.g., representing nested database entities), in this tutorial, a DTO instance will correspond to an action on a single database row.

Why DTOs?

Using DTOs to align TypeScript objects with data models enforces architectural consistency. However, it’s crucial to understand that neither DTOs nor TypeScript alone provide automatic user input validation, which must occur at runtime. User input received at an API endpoint might:

- Contain extraneous fields

- Lack required fields (those not marked optional with

?in TypeScript) - Have fields with data types different from those defined in the model

TypeScript (and the resulting JavaScript) won’t catch these issues at runtime (won’t magically check this). Validations are vital, especially for public APIs. Libraries like ajv can help but often rely on their own schema definitions instead of native TypeScript types. (Mongoose, covered in the next article, will serve a similar purpose in this project.)

You might wonder about the necessity of both DAOs and DTOs. As experienced developer Gunther Popp offers an answer, DTOs might be overkill for smaller Express.js/TypeScript projects unless significant scaling is anticipated.

Even if you’re not immediately using them in production, this example project offers valuable practice in:

- Utilizing TypeScript types for data modeling (in additional ways)

- Working with DTOs to understand their benefits and drawbacks compared to simpler approaches when adding components and models

Our User REST API Model at the TypeScript Level

Let’s define three DTOs for users. Create a dto folder within the users folder, and within it, create create.user.dto.ts:

| |

This code defines a CreateUserDto interface, specifying the required fields (ID, password, email) and optional fields (firstName, lastName) when creating a user, regardless of the database used. These requirements can vary based on project needs.

For PUT requests (complete object updates), optional fields become required. In the same folder, create put.user.dto.ts:

| |

For PATCH requests (partial updates), TypeScript’s Partial utility comes in handy. It creates a new type with all fields of the original type marked optional. Create patch.user.dto.ts:

| |

Now, let’s set up the temporary in-memory database. Create a daos folder inside users and add users.dao.ts.

Begin by importing the DTOs:

| |

Install the shortid library for generating unique IDs:

| |

In users.dao.ts, import shortid:

| |

Now, create the UsersDao class:

| |

This class uses the singleton pattern, ensuring that importing it from different files always returns the same instance with the same users array. This is due to Node.js’s module caching—the first instance of UsersDao is cached and reused.

This pattern will be evident as we use this class later in the article. It’s a common practice in TypeScript/Express.js projects for most classes.

Note: Singletons can be harder to unit test. This won’t be a major concern for many of our classes, as they lack member variables requiring resetting. For those that do, consider techniques like dependency injection (dependency injection).

Next, add basic CRUD operations as functions to the class. The create function:

| |

Read operations: one for fetching all users, another for retrieving by ID:

| |

Similarly, update can be a full replacement (PUT) or a partial modification (PATCH):

| |

Importantly, despite using UserDto in function signatures, TypeScript doesn’t enforce these types at runtime. This means:

putUserById()has a potential issue—it doesn’t prevent storing data for fields not defined in the DTO.patchUserById()relies on a separate list of field names that need to be kept in sync with the model. Without this, it might silently ignore fields defined in the DTO but missing from the object being updated.

These scenarios will be handled correctly at the database level in the next article.

The final operation, delete, is straightforward:

| |

Additionally, let’s add a “get user by email” function, a common requirement before creating a user (to prevent duplicates):

| |

Note: In real-world scenarios, you’d typically use database libraries like Mongoose or Sequelize to abstract away these basic operations. This tutorial skips those details for simplicity.

Our REST API Services Layer

With a basic DAO, we can create a service that utilizes its CRUD functions. Since these operations are fundamental, let’s define a CRUD interface that services connecting to databases can implement.

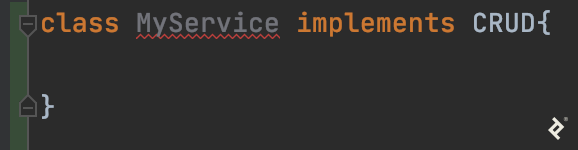

Many IDEs now offer code generation to reduce boilerplate. For example, in WebStorm IDE:

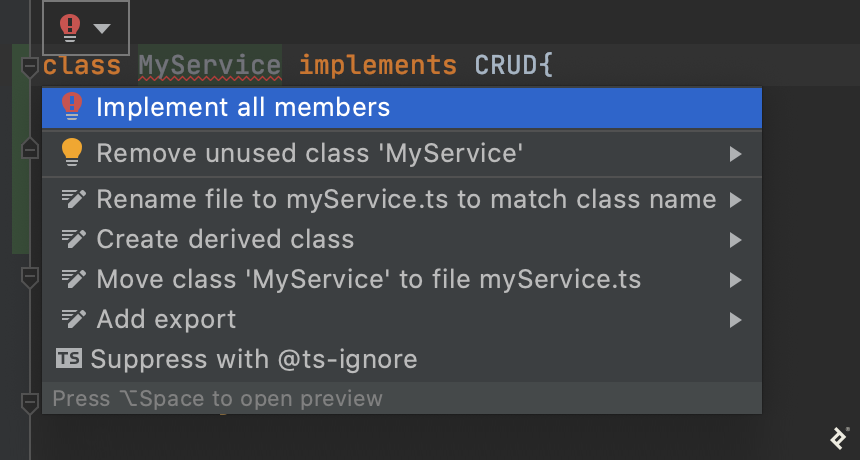

The IDE might suggest:

Choosing “Implement all members” would automatically generate the functions needed to conform to the CRUD interface:

First, create the CRUD interface. Within the common folder, create an interfaces folder and add crud.interface.ts:

| |

Now, create a services folder within users and add users.service.ts:

| |

This code imports the in-memory DAO, the CRUD interface, and DTO types. UsersService is implemented as a singleton, mirroring the DAO pattern.

All CRUD functions simply delegate to their counterparts in UsersDao. If the DAO changes in the future, modifications are localized to this service file, thanks to the separation of concerns.

For instance, replacing the list() function wouldn’t require hunting down every usage throughout the codebase. This modularity comes at the cost of some initial boilerplate.

Async/Await and Node.js

The use of async in service functions might seem unnecessary at this point. They currently return values directly without utilizing Promises or await. This is intentional to prepare for future services that will incorporate asynchronous operations. Similarly, you’ll notice await used when calling these functions.

By the end of this article, you’ll have a functional project. It’s a good opportunity to experiment with introducing errors at various points and observing the behavior during compilation and testing. Errors in async contexts can behave unexpectedly. It’s worth exploring topics like error handling in asynchronous JavaScript and the event loop (exploring various solutions) beyond the scope of this article.

With the DAO and services in place, let’s move on to the user controller.

Building Our REST API Controller

Controllers separate route handling logic from route configuration. Ideally, validations occur before a request reaches the controller. The controller assumes a valid request and focuses solely on processing it. It achieves this by calling the appropriate service functions.

Before proceeding, install the bcrypt library for password hashing:

| |

Create a controllers folder inside the users folder and add users.controller.ts:

| |

Note: Sending a 204 No Content response without a body for successful PUT, PATCH, and DELETE requests aligns with common REST practices (RFC 7231).

The user controller is implemented as a singleton. Next, let’s work on user middleware, which also depends on the API object model and service.

Node.js REST Middleware with Express.js

Middleware is well-suited for validations. Let’s add some basic validation checks:

- Verify the presence of required fields like

emailandpasswordfor user creation and updates. - Ensure that email addresses are unique.

- Prevent modifications to the

emailfield after user creation (treating it as a primary identifier for simplicity). - Check if a user with the given ID exists.

These validations need to be adapted into Express.js middleware functions using the next() function for control flow, as covered in the previous article. Create users/middleware/users.middleware.ts:

| |

After the singleton setup, add middleware functions to the class:

| |

To simplify subsequent requests related to a newly created user, let’s add a helper function to extract the userId from request parameters (the URL) and add it to the request body (containing other user data).

This way, when updating user information, the ID is readily available in the request body, avoiding repeated retrieval from parameters. This logic is centralized in the middleware. Add the following function:

| |

The key difference between middleware and controllers lies in the use of next() to pass control along the middleware chain until it reaches the final destination (the controller).

Putting it All Together: Refactoring Our Routes

With the new architecture in place, revisit users.routes.config.ts from the previous article. Update it to use the middleware and controllers, which in turn rely on the user service and model.

The final version of the file should look like this:

| |

This code defines routes with middleware for validation and controller functions for processing valid requests. The .param() method from Express.js extracts the userId.

The .all() method applies validateUserExists from UsersMiddleware to all GET, PUT, PATCH, and DELETE requests targeting /users/:userId. This eliminates the need to repeat it for each HTTP method.

Middleware reusability is demonstrated by using UsersMiddleware.validateRequiredUserBodyFields for both POST and PUT requests, streamlining common validation logic.

Disclaimers: This article covers basic validations. Real-world projects often demand more comprehensive checks. For simplicity, we assume email addresses cannot be changed.

Testing Our Express/TypeScript REST API

Now, compile and run the Node.js application. Once it’s running, use a REST client like Postman or cURL to test the API routes.

First, attempt to fetch all users:

| |

The response should be an empty array, as expected. Now, try creating a user:

| |

This request should result in an error from the middleware:

| |

Fix the request by providing the required fields:

| |

The response should resemble:

| |

The id is unique to the created user. Store this ID in a variable for subsequent tests (assuming a Linux-like environment):

| |

Fetch the user using the stored ID:

| |

Update the entire user resource using a PUT request:

| |

Test the email validation by attempting to change the email address, which should trigger an error.

Remember that PUT requests expect the entire object to be provided. To update only the lastName field, use a PATCH request instead:

| |

This distinction between PUT and PATCH is enforced by the route configuration and middleware.

PUT, PATCH, or Both?

It may sound like there’s not much reason to support PUT given the flexibility of PATCH, and some APIs will take that approach. Others may insist on supporting PUT to make the API “completely REST-conformant,” in which case, creating per-field PUT routes might be an appropriate tactic for common use cases.

In reality, these points are part of a much larger discussion ranging from real-life differences between the two to more flexible semantics for PATCH alone. We present PUT support here and widely-used PATCH semantics for simplicity, but encourage readers to delve into further research when they feel ready to do so.

Fetch the user list again:

| |

Finally, test deleting the user:

| |

Fetching the user list once more should confirm that the user is no longer present.

This completes the implementation and testing of basic CRUD operations for the users resource.

Node.js/TypeScript REST API

This part of the series explored building a REST API using Express.js, focusing on services, middleware, controllers, and models. Each component plays a distinct role, from validation and business logic to request processing and response generation.

A simple in-memory database was used for demonstration purposes. In the next part, it will be replaced with a more robust solution using MongoDB and Mongoose.

The series will conclude by covering:

- Integrating MongoDB and Mongoose for data persistence

- Implementing JWT-based authentication for stateless security

- Setting up automated testing for scalability

You can find the code for this part of the series here.