It’s clear that some struggle with, or even completely neglect, proper error handling. Yet, it’s crucial not only for faster development through easier bug detection but also for building robust large-scale applications.

Node.js developers, in particular, often grapple with messy code and inconsistent error handling, leading them to question Node.js’s error-handling capabilities. However, the responsibility lies with us developers, not the framework itself.

Here’s a solution I find particularly effective.

Node.js Error-handling: Error Types

A clear understanding of Node.js errors is paramount. They fall into two categories: operational errors and programmer errors.

- Operational errors are expected runtime issues requiring proper handling. They don’t indicate application flaws but necessitate careful management. Examples include “out of memory” or invalid API endpoint inputs.

- Programmer errors are unexpected bugs stemming from flawed code, signaling issues within the code itself. An example is attempting to access a property of “undefined.” Fixing this requires code modification – it’s a developer error, not an operational one.

Distinguishing these is crucial: operational errors are inherent, while programmer errors are developer-induced bugs. This distinction begs the question: “Why differentiate and handle them differently?”

Without this clarity, you might consider restarting your application for every error. But restarting due to a “File Not Found” error while thousands are actively using the application is illogical.

Conversely, allowing an application to run with an unknown bug that could snowball into a larger issue is equally unwise!

Towards Proper Error Handling

If you’ve worked with async JavaScript and Node.js, you’ve likely encountered the drawbacks of callback-based error handling. Nested callbacks lead to the infamous “callback hell,” hindering code readability.

Promises or async/await offer a better alternative. Here’s a typical async/await flow:

| |

Leveraging Node.js’s built-in Error object is recommended, as it provides insightful information like the StackTrace, invaluable for tracing error origins. Extending the Error class with properties like HTTP status codes and descriptions enhances clarity further.

| |

For brevity, I’ve included only a few HTTP status codes, but feel free to add more.

| |

While extending BaseError or APIError isn’t mandatory, it can be beneficial for common errors, based on your needs.

| |

Here’s how to use it:

| |

Centralized Node.js Error-handling

Now, let’s build the core of our Node.js error-handling system: the centralized error-handling component.

A centralized component prevents code duplication during error handling. It interprets caught errors by, for example, notifying admins, pushing events to services like Sentry.io, and logging them.

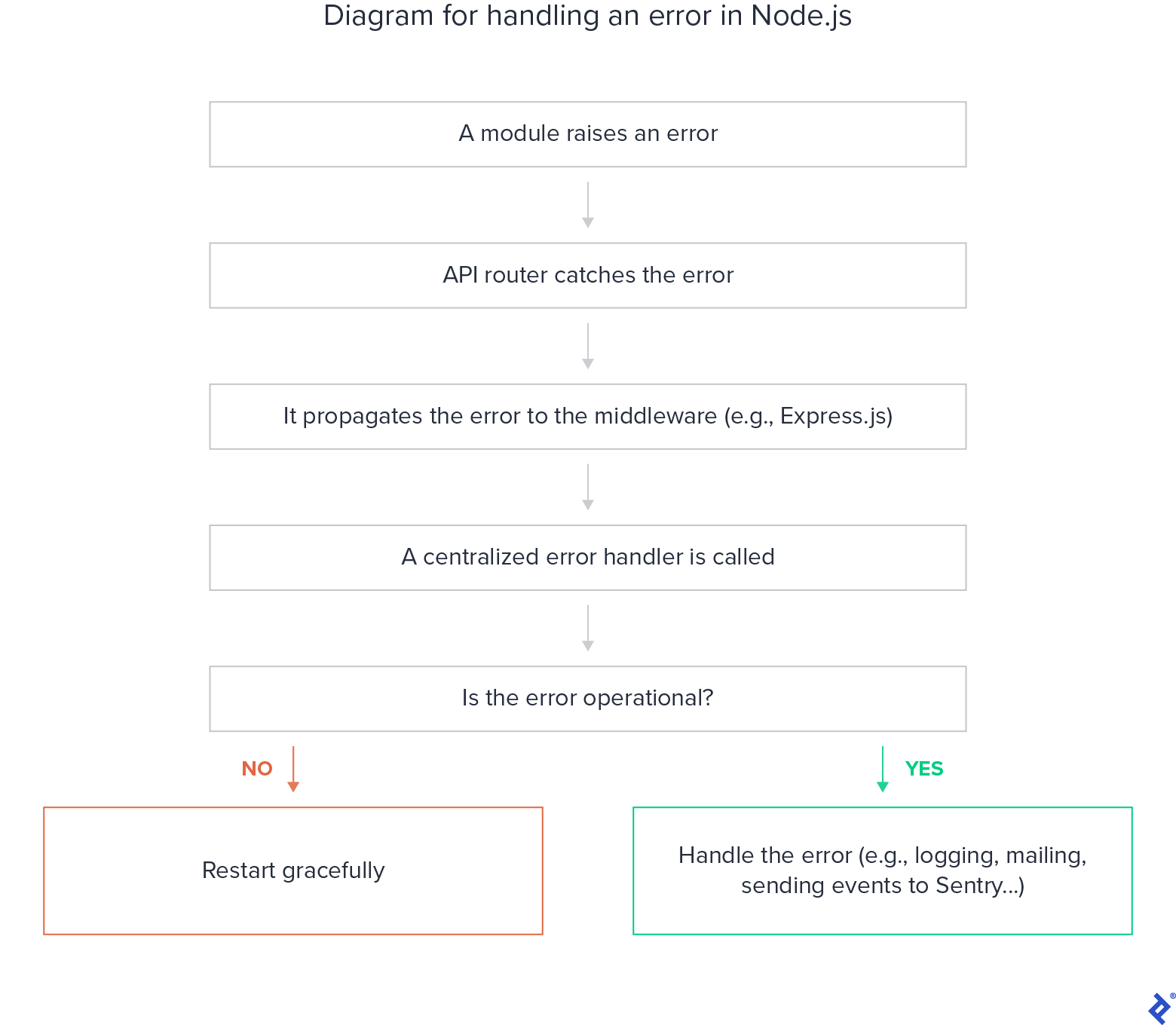

Here’s a basic error-handling workflow:

In certain code sections, caught errors are passed to an error-handling middleware.

| |

This middleware acts as a triage, differentiating error types and routing them to the centralized error-handling component. Familiarity with Express error-handling basics](https://expressjs.com/en/guide/error-handling.html) is beneficial here, as is a deeper dive into best practices with Promises.

| |

By now, you likely envision the centralized component’s structure, as we’ve used some of its functionalities. Implementation is flexible, but here’s a potential structure:

| |

The default “console.log” output can be difficult to parse. A formatted output is more effective, allowing developers to swiftly understand and address issues.

This streamlined approach saves time and enhances error visibility and management. Employing a customizable logger like winston or morgan is a wise choice.

Here’s a custom Winston logger:

| |

This logger provides multi-level logging with formatting and colors, outputting to different media based on the runtime environment. It allows log viewing and querying through Winston’s APIs. You can even integrate log analysis tools for further insights. Powerful, right?

So far, we’ve focused on operational errors. What about programmer errors? The optimal approach here is an immediate crash followed by a graceful restart using an auto-restarter like PM2. Why? Because these are unexpected bugs that can leave the application in an unpredictable, potentially harmful state.

| |

Finally, let’s address unhandled promise rejections and exceptions.

Promise handling is common in Node.js/Express applications. Forgetting to handle rejections often leads to “unhandled promise rejection” warnings.

These warnings merely log the issue. A better practice is to implement a robust fallback and subscribe to process.on(‘unhandledRejection’, callback), acting as a global Node.js error handler.

A typical error-handling flow could look like this:

| |

Error-handling in Node.js: Essential, Not Optional

Error-handling is not optional – it’s fundamental for development and production.

Centralizing error handling in Node.js saves time and promotes clean, maintainable code by minimizing duplication and preserving error context.

I hope this article provided valuable insights and that the discussed workflow and implementation help you build robust Node.js applications.