The significance of data quality in data warehouse systems is steadily increasing. The combination of stricter regulatory requirements and increasingly intricate data warehouse solutions necessitates that businesses prioritize and invest in data quality (DQ) initiatives.

While this article primarily centers on conventional data warehousing, it acknowledges the relevance of data quality in more contemporary approaches like data lakes. It will present key considerations and highlight prevalent pitfalls to circumvent when establishing a data quality strategy. However, it won’t delve into selecting the appropriate technology or tools for constructing a DQ framework.

A significant obstacle in DQ projects is the initial perception of increased workload for business units without tangible functional gains. Strong support for data quality initiatives usually arises when:

- Data quality issues noticeably impact business operations.

- Regulatory bodies mandate adherence to data quality standards (e.g., BCBS 239 in the financial sector).

DQ often receives similar treatment to testing in software development—it tends to be the first area scaled back when projects face time or budget constraints.

However, this perspective overlooks the long-term benefits. A robust data quality system facilitates early error detection, accelerating the delivery of sufficiently high-quality data to users.

Defining Key Terms

Before delving further, establishing a shared understanding of the terminology used is crucial.

Data Warehouse (DWH)

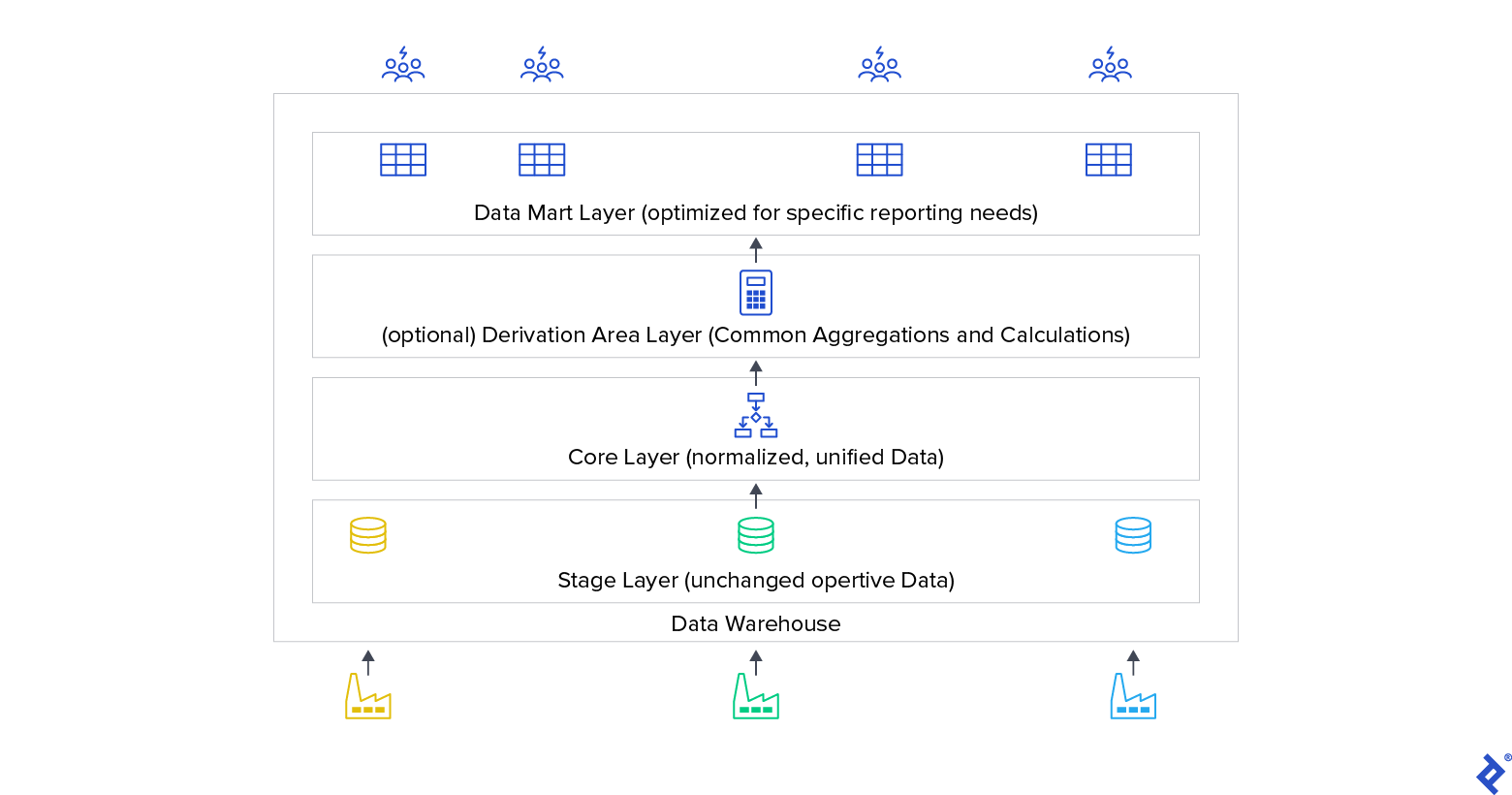

A data warehouse (DWH) is a non-operational system primarily designed for decision support. It integrates data from operational systems (either comprehensively or a focused subset) and offers query-optimized data to DWH system users, aiming to provide a unified and reliable “single version of truth” within the organization. A data warehouse typically consists of stages or layers:

Operational data is initially stored, mostly unaltered, in a staging layer. The core layer houses consolidated and standardized data. An optional derivation area may follow, providing derived data (e.g., customer scores for sales) and aggregations. The data mart layer contains data tailored for specific user groups, often including aggregations and derived metrics. Data warehouse users frequently interact solely with the data mart layer.

Data transformation occurs between each stage. Data warehouses are typically loaded periodically with incremental updates from operational data and incorporate mechanisms to retain historical data.

Data Quality

Data quality is typically defined as a measure of how effectively a product aligns with user expectations. As different user groups may have varying requirements, data quality implementation hinges on the user’s viewpoint, making it vital to identify these specific needs.

Data quality doesn’t necessarily equate to completely or near-error-free data—it depends on the user’s requirements. A “good enough” approach serves as a practical starting point. Many large organizations now have “data (or information) governance policies,” with data quality as a key component. A data governance policy should outline the company’s data management practices, ensuring appropriate data quality and adherence to data privacy regulations.

Data quality is an ongoing concern, requiring the implementation of a DQ circuit loop (discussed in the subsequent section). Regulatory requirements and compliance standards, such as TCPA (US Telephone Consumer Protection Act), GDPR for privacy in Europe, and industry-specific regulations like Solvency II for insurance in the EU, BCBS 239 and others for banking, also influence the required level of data quality.

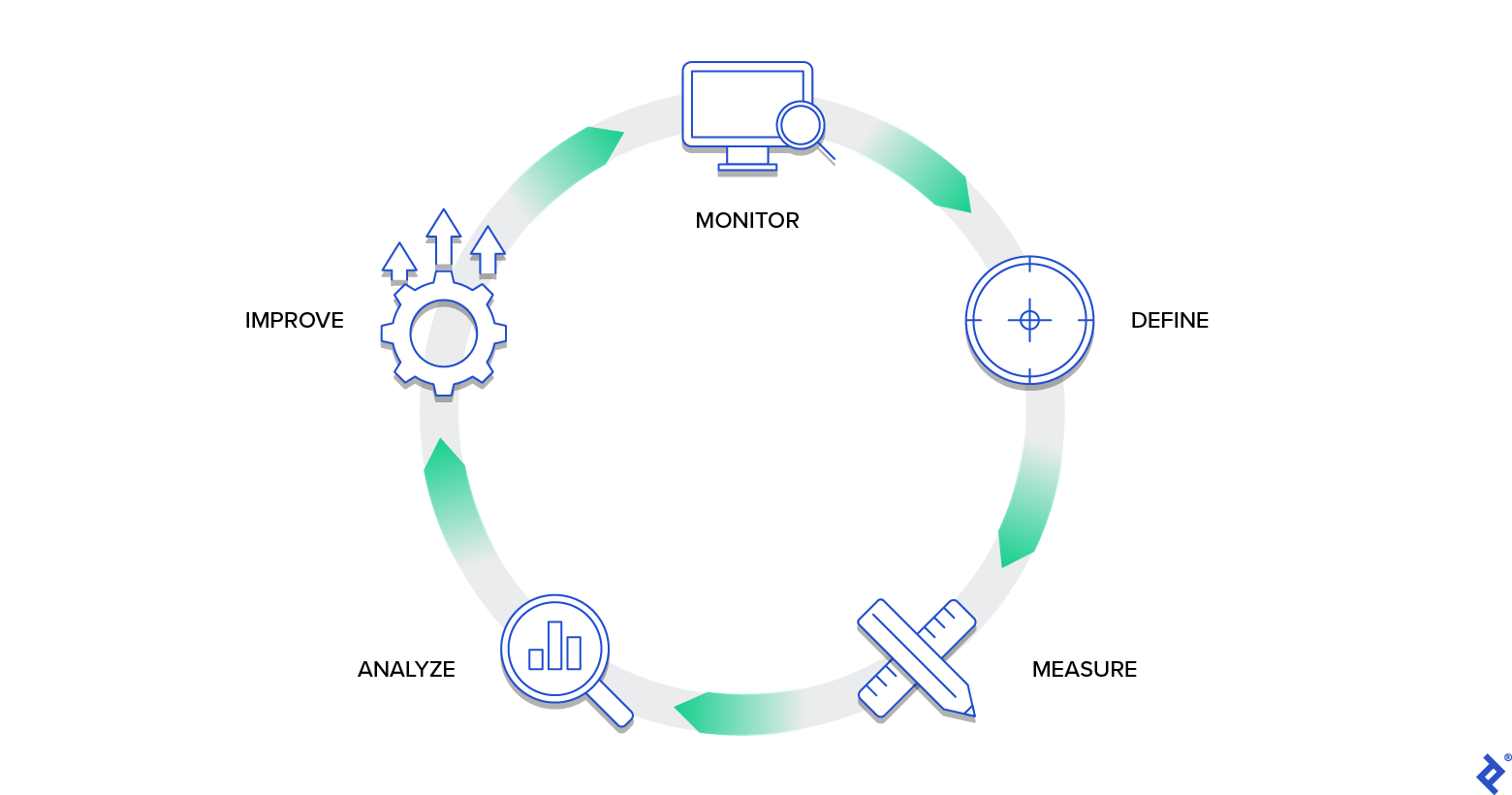

Data Quality Circuit Loop

Like all quality-related endeavors, DQ is a continuous process to sustain satisfactory quality. A DQ project should result in the implementation of a circuit loop resembling the following:

The steps within this loop will be elaborated upon in the following sections.

Roles in Data Quality

Next, we’ll explore methods for enhancing data quality in data warehousing and implementing successful DQ initiatives. The following roles are essential in this process:

- Data Owner. Responsible for data quality and data privacy, the data owner “owns” a data domain, manages access, ensures data quality, and addresses any identified issues. Larger organizations often have multiple data owners for different data domains (e.g., marketing data, financial data). If multiple data owners exist, a designated individual (data owner or otherwise) should oversee the overall data quality process. Data owners require sufficient authority to enforce data quality and support the DQ process, often making them senior stakeholders. Strong business domain knowledge and effective communication skills are crucial for this role.

- Data Steward. Supporting data users with data interpretation, data model understanding, and data quality issues, data stewards facilitate data quality implementation within an organization. They often work under the data owner or as part of a data quality competence center or team. Data stewards can come from IT or business backgrounds but should possess knowledge of both areas. Analytical skills, coupled with a solid understanding of the supported business domain and strong communication skills, are key attributes for successful data stewards.

- Data User. These are individuals working directly with data within the data warehouse, typically interacting with the data mart layer and responsible for the outcomes of their data-driven work. Data users ensure adequate data quality checks for their required quality levels. They need a strong grasp of their data, the business domain, and the analytical skills to interpret data. It’s advisable to have designated individuals within each business unit responsible for addressing data quality concerns.

Clear definition and organization-wide acceptance of these roles during the initial stages of a DQ project are crucial for its success. Equally important is identifying and appointing skilled data professionals who are genuinely committed to supporting the project.

Establishing DQ Rules in Data Warehousing

There’s a strong interdependence between data quality and data warehousing. Defining effective data quality rules requires a thorough understanding of the data warehouse itself.

Identifying DQ Rules

As emphasized earlier, data users (along with the data owner) bear the responsibility for data utilization and, consequently, the necessary level of data quality. Their insights into the data make them invaluable contributors to defining practical data quality rules.

Data users, as the primary analyzers of data quality rule outcomes, benefit from defining their own rules. This fosters greater acceptance when evaluating and assessing the results of DQ rules assigned to their respective units (see “Analyze” section).

However, this approach has a limitation—data users typically only work with the data mart layer, not the underlying layers of the data warehouse. Errors introduced in earlier stages might go undetected if checks are limited to the “top” layer.

Addressing Errors

What types of errors commonly occur in a data warehouse?

- Incorrect Transformation Logic in the Data Warehouse: The complexity of your IT landscape often correlates with the complexity of data transformation logic. These are among the most frequent DQ issues, potentially leading to data loss, duplication, inaccurate values, and more.

- Unstable Load Processes or Load Handling Errors: Data warehouse loading can be intricate, with potential errors in job orchestration (e.g., jobs starting out of sequence, unexecuted jobs). Manual intervention (e.g., skipping jobs, initiating jobs with incorrect dates or outdated data files) often introduces errors, especially during out-of-band load process executions due to disruptions.

- Data Source Transfer Errors: Data transfer is frequently managed by the source system. Anomalies or interruptions in job flows can result in incomplete or empty data deliveries.

- Inaccurate Operational Data: Errors present in the operational system but not yet identified can impact data quality. While it might seem counterintuitive, data warehouse projects often reveal data quality issues in the operational data only after it’s integrated into the DWH.

- Data Misinterpretation: While the data itself is correct, users might misinterpret it. This common “error” falls under data governance and is a task for data stewards rather than a strict data quality issue.

These problems often stem from a lack of adequate knowledge and skills in defining, implementing, operating, and utilizing data warehouse solutions.

Data Quality Dimensions

DQ dimensions provide a structured approach to categorize and group DQ checks. Numerous definitions exist, with varying numbers of dimensions (e.g., 16 or more). Practically, it’s best to start with a few dimensions and ensure a shared understanding among users.

- Completeness: Is all necessary data present and accessible? Are required sources available and loaded? Has data been lost during transformations?

- Consistency: Does the data contain errors, conflicts, or inconsistencies? For example, the termination date of a “Terminated” contract should logically be a valid date equal to or later than the contract start date.

- Uniqueness: Are there duplicate records?

- Integrity: Are data relationships correctly established? For instance, are there orders linked to non-existent customer IDs (a classic referential integrity issue)?

- Timeliness: Is the data up-to-date? In a data warehouse with daily updates, yesterday’s data should be available today.

Data generated by the data warehouse load process can also be insightful.

- Tables for Discarded Data: Data warehouses might employ processes to bypass or delay data that can’t be loaded due to technical problems (e.g., format conversion issues, missing mandatory values).

- Logging Information: Logs, either in tables or files, can capture significant issues.

- Bill of Delivery: Some systems utilize “bills of delivery” for data received from operational systems, providing details like record counts, distinct key counts, and value sums. These can be used for reconciliation checks (discussed later) between the data warehouse and operational systems.

It’s crucial to remember that at least one data user should analyze each data quality check (see the “Analyze” section) in case errors are found. Having someone accountable and available to review every implemented check is essential.

Complex data warehouses can result in numerous (sometimes thousands) of DQ rules. Ensure your execution process for data quality rules is robust and efficient enough to manage this volume.

Avoid redundant checks. Don’t waste resources checking aspects guaranteed by the technical implementation. For example, if using a relational DBMS, there’s no need to check if:

- Columns defined as mandatory contain NULL values.

- Primary key field values are unique within a table.

- Foreign key relationships are violated if referential integrity checks are active.

However, remember that data warehouses constantly evolve, and field and table definitions can change over time.

Housekeeping is essential. Consolidate overlapping rules defined by different data user groups. More complex organizations will require more extensive housekeeping efforts. Data owners should establish a process for rule consolidation as a form of “data quality for data quality rules.” Additionally, retire data quality checks that become obsolete if the data is no longer used or its definition changes.

Classifying Data Quality Rules

Data quality rules can be grouped based on their test type:

- Data Quality Check: The standard case, verifying data within a single data warehouse layer (refer to Figure 1), either within a single table or across multiple tables.

- Reconciliation: Rules that validate the accurate transfer of data between data warehouse layers (see Figure 1), primarily used to check the “Completeness” DQ dimension. Reconciliation can be row-level or summarized. Row-level checks offer greater granularity but require replicating transformation steps (e.g., data filtering, field value modifications, denormalization, joins) between the compared layers. The more layers skipped, the more complex the transformation logic becomes. Therefore, it’s advisable to perform reconciliation between each layer and its predecessor rather than comparing the staging layer directly to the data mart layer. If transformations are needed for reconciliation rules, use the specification, not the data warehouse code. For summarized reconciliation, identify meaningful fields (e.g., aggregations, distinct value counts).

- Monitoring: Data warehouses often store historical data and are loaded with incremental extracts of operational data. This introduces the risk of a growing discrepancy between the data warehouse and the operational systems over time. Building summarized time series data helps identify such issues (e.g., comparing last month’s data with the current month’s data). Data users familiar with their data can provide valuable metrics and thresholds for monitoring rules.

Quantifying Data Quality Issues

Once you’ve defined what to check, specify how to measure identified issues. Information like “five data rows violate DQ rule with ID 15” lacks context for data quality assessment.

The following aspects are missing:

- Error Quantification/Counting: Go beyond simply counting rows; consider monetary scales (e.g., exposure). Remember that monetary values might have different signs, requiring careful summarization. Using both quantification units (row counts and summarizations) for a data quality rule can be beneficial.

- Population: What’s the total number of units examined by the data quality rule? “Five data rows out of five” signifies different quality compared to “five out of five million.” Measure the population using the same units as for errors. Expressing data quality rule results as percentages is common. The population shouldn’t always be the total row count in a table. If a DQ rule focuses on a subset of data (e.g., only terminated contracts in a contracts table), apply the same filter when determining the population.

- Result Definition: Even when a data quality check identifies issues, it shouldn’t always be classified as an error. A traffic light system (red, yellow, green) with threshold values to rate findings is helpful for data quality. For example, green: 0-2%, yellow: 2-5%, red: above 5%. Consider that different data user units sharing the same rules might have different thresholds. A marketing unit might tolerate a few lost orders, while an accounting unit might be concerned about even minor discrepancies. Allow threshold definitions based on percentages or absolute figures.

- Sample Error Rows: Include a sample of detected errors within the data quality rule output—typically, business keys and checked data values are sufficient for investigation. It’s advisable to limit the number of error rows written for a single data quality rule.

- Whitelists: Sometimes, you might encounter “known errors” in the data that won’t be fixed immediately but are flagged by useful data quality checks. In these cases, implement whitelists (lists of record keys to be ignored by a data quality check).

Additional Metadata

Metadata is vital for directing the “Analyze” and monitoring phases of the data quality control loop.

- Checked Items: Associate the checked table(s) and field(s) with a data quality rule. An advanced metadata system can leverage this information to automatically assign data users and data owners to the rule. For regulatory purposes (like BCBS 239), demonstrating how data is checked via DQ is essential. However, automatic assignment of rules to data users/data owners through data lineage (*) can be problematic (see below).

- Data User: Assign at least one data user or data user unit to each DQ rule to review the results during the “Analyze” phase and determine how findings impact their work.

- Data Owner: Every DQ rule must have a designated data owner.

(*) Data lineage illustrates the flow of data between two points, allowing you to trace all data elements influencing a specific target field within your warehouse.

Using data lineage for user assignment to rules can be problematic. As noted earlier, business users often only understand the data mart layer (and potentially the operational systems) but not the lower levels of the data warehouse. Data lineage mapping might assign them rules they’re unfamiliar with. IT staff might be needed to evaluate data quality findings in lower layers. Manual mapping or a hybrid approach (data lineage mapping only within the data mart) can be more effective.

Measuring Data Quality

Measuring data quality involves executing the defined data quality rules, which should be an automated process triggered by the data warehouse load processes. Given the potentially large number of data quality rules, these checks can be time-consuming.

Ideally, data warehouses would only be loaded with error-free data. However, in reality, this is rarely the case. Your data quality process should integrate with the overall loading strategy, but it shouldn’t (and likely won’t) dictate the entire load process. A recommended design is to have data quality processes (job networks) running in parallel and linked to the “regular” data warehouse load processes.

If service-level agreements are in place, ensure data quality checks don’t impede data warehouse loads. Errors or issues within data quality processes shouldn’t halt the regular loading process. Report unexpected errors within the data quality processes and surface them during the “Analyze” phase (discussed next).

Keep in mind that data quality rules can fail due to unforeseen errors (e.g., rule implementation errors, underlying data structure changes). It’s helpful if your data quality system allows deactivating such rules, especially in organizations with infrequent releases.

Execute and report DQ processes as early as possible, ideally immediately after loading the checked data. This facilitates early error detection during the data warehouse load process, which can span several days in complex systems.

Analyze

“Analyze” in this context refers to responding to data quality findings, a task for the assigned data users and data owner.

Your data quality project should clearly define the response protocol. Data users should be obligated to provide comments on rules with findings (especially those flagged as red), explaining the actions taken to address the issue. Inform the data owner, who will then collaborate with the data user(s) to determine the appropriate course of action.

Possible actions include:

- Serious Problem: The issue requires immediate resolution, necessitating a data reload after the fix.

- Acceptable Problem: While aiming to fix it for future loads, manage the problem within the data warehouse or reporting for the current load.

- Defective DQ Rule: Correct the problematic data quality rule.

Ideally, every data quality problem would be resolved. However, resource or time constraints often lead to workarounds.

To enable timely responses, the DQ system must notify data users about findings related to “their” rules. A data quality dashboard (potentially with notifications) is highly recommended. The sooner users are informed, the better.

The data quality dashboard should provide:

- A view of all rules assigned to a given role.

- Rule results (traffic light status, measures, sample rows) with filtering options based on result and data domain.

- A mandatory comment section for data users to document their assessment of findings.

- An option to “override” the result (e.g., if the data quality rule flags errors due to a faulty implementation). In cases where multiple business units share a data quality rule, “overriding” should only apply to the data user’s unit, not company-wide.

- Visibility into unexecuted or failed rules.

The dashboard should also display the current status of the recent data warehouse load process, offering users a comprehensive view.

The data owner is responsible for ensuring that every finding receives a comment and that the data quality status (original or overridden) is at least yellow for all data users.

Simple KPIs (key performance indicators) for data users and data owners can provide a quick overview. Displaying an overall traffic light status for all associated rule results is relatively straightforward if each rule carries equal weight.

Calculating an overall data quality value for a specific data domain can be complex and potentially arbitrary. However, you can at least show the total number of rules grouped by their result for a data domain (e.g., “100 DQ rules with 90% green, 5% yellow, and 5% red results”).

The data owner is ultimately accountable for ensuring that findings are addressed and data quality is improved.

Process Improvement

Data warehouse processes evolve, and so should the data quality mechanism.

Data owners should prioritize the following:

- Keep It Up-to-Date: Reflect changes in the data warehouse within the data quality system.

- Enhance: Implement new rules to cover errors not yet addressed by existing data quality rules.

- Streamline: Retire obsolete data quality rules and consolidate overlapping ones.

Monitoring Data Quality Processes

Monitoring the entire data quality process helps identify areas for improvement.

Key metrics to track include:

- The extent of data coverage by data quality rules.

- The percentage of data quality findings within active rules over time.

- The number of active data quality rules (monitor for potential issues like data users disabling rules to avoid addressing findings).

- The time required within a data load cycle to have all findings assessed and resolved.

Final Data Warehouse Data Quality Process Tips

Many of these points hold true for various types of projects.

Expect Resistance: As mentioned earlier, data quality is often perceived as an added burden without immediate functional benefits, especially when no urgent quality issues exist. Be prepared to address concerns about potential workload increases for data users. Compliance and regulatory requirements can be helpful in convincing users of its necessity.

Secure a Sponsor: DQ isn’t always easy to promote. Having a strong sponsor or stakeholder, preferably from higher management, is invaluable.

Find Allies: Similar to a sponsor, anyone who supports the importance of strong data quality can be a valuable asset. The DQ circuit loop is an ongoing process that needs dedicated individuals to keep it running effectively.

Start Small: If a DQ strategy is lacking, identify a business unit with a clear need for better data quality. Develop a prototype to demonstrate the benefits. If tasked with improving or replacing an existing data quality strategy, identify and retain elements that work well and are accepted within the organization.

Maintain a Holistic Perspective: While starting small is practical, remember that certain aspects, particularly well-defined roles, are crucial for a successful DQ strategy.

Sustained Effort: Integrate the data quality process as an integral part of data warehouse use. Over time, the focus on data quality might wane. It’s your responsibility to champion its continued importance.