GWT Web Toolkit, previously known as Google Web Toolkit, provides a collection of development tools for creating and enhancing sophisticated browser-based applications using Java.

GWT’s uniqueness lies in its compiler, which transforms Java code into JavaScript, HTML, and CSS. This allows developers to build front-end web applications while enjoying the advantages of Java.

The seamless integration of Java and JavaScript is facilitated by GWT’s robust interoperability architecture. Similar to how the Java Native Interface (JNI) enables the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) to interact with platform-specific routines, GWT allows developers to write most of an application in Java. When needed, they can leverage specific web APIs or existing JavaScript libraries by seamlessly transitioning into JavaScript.

Originating as a Google product, GWT transitioned to open source in late 2011 under the Apache License (Version 2) and is now known as the GWT Open Source Project. It is overseen by a steering committee comprising representatives from various companies such as Google, RedHat, ArcBees, Vaadin, and Sencha, along with independent developers.

The Journey and Future of GWT

GWT was initially released in 2006 to assist Google engineers in developing complex browser-based applications like AdWords, Google Wallet, Google Flights, and more recently, Google Sheets and Inbox.

Back then, browsers and JavaScript interpreters lacked standardization. Front-end code was inefficient, error-prone, and challenging to use reliably. High-quality libraries and frameworks for web development were virtually nonexistent. For building large-scale web applications, Google engineers decided to utilize their existing tools and expertise. Java was the ideal choice due to its familiarity, seamless IDE integration, and capabilities, leading to the creation of GWT.

The primary objective was to abstract away browser inconsistencies and encapsulate the intricacies of writing efficient JavaScript within a Java compiler, freeing developers from browser-specific complexities.

Over the past decade, the web landscape has transformed significantly. Browsers have become faster and more standardized, and numerous exceptional front-end frameworks and libraries have emerged, including jQuery, Angular, Polymer, and React. This raises the question, “Is GWT still relevant?”

The answer is a resounding Yes.

In contemporary web development, browser targeting is crucial, and JavaScript has become the dominant language for front-end applications. However, different tools and languages are better suited for specific tasks. GWT, along with other similar projects, aims to target browsers without limiting developers to JavaScript.

The development and use of “compile-to-the-web” tools like GWT will be further aided by the World Wide Web Consortium’s WebAssembly group. This approach not only offers significant potential for tools that compile to JavaScript but also addresses the need for offloading computations to browsers, reusing existing code and libraries, sharing code between back-end and front-end, leveraging existing skills and workflows, and utilizing features of different languages (such as static typing in GWT).

The GWT Project is preparing to release version 2.8 soon, with version 3.0 in development. These versions promise significant enhancements, including:

- Improved interoperability with JavaScript

- A significantly enhanced (almost entirely rewritten) compiler

- Support for modern Java features (e.g., lambdas)

Most of GWT 3.0’s features are already available on the public Git repository. You can access the trunk, here, and compile GWT following the instructions in the documentation here.

The GWT Community

Since becoming open source in 2011, the GWT community has played a vital role in the project’s growth.

All development takes place on the Git repository hosted on gwt.googlesource.com, with code reviews conducted on gwt-review.googlesource.com. These platforms provide a space for anyone interested in GWT’s development to contribute and stay updated on community efforts. In recent years, the contribution of non-Google developers has increased from approximately 5 percent in 2012 to around 25 percent in the previous year, highlighting the growing community engagement.

This year, the community has organized several large gatherings in the U.S. and Europe. GWT.create, organized by Vaadin, took place in Munich, Germany, and Mountain View, California, in January, attracting over 600 attendees from various countries. On November 11th, Florence, Italy will host the second edition of GWTcon, a community-driven GWT conference which I am assisting in organizing.

Ideal Use Cases for GWT

Vaadin conducts an annual survey on GWT, exploring its development trajectory, developer perspectives, strengths, weaknesses, and more. The survey reveals how GWT is being utilized, how the user base is evolving, and developers’ expectations for the toolkit’s future.

The Future of GWT Report for 2015 is available here. It highlights the popularity of GWT for building large-scale web applications. Page 14 states, “Most applications are business applications that are data-intensive and are used for many hours per day.”

Unsurprisingly, GWT excels in developing large-scale web applications where code maintainability is crucial, and large teams benefit from Java’s structured approach.

Benchmarks for GWT-generated code (see keynote of last year’s GWT.create conference, pages 7, 8, and 11) demonstrate that the compiled JavaScript is exceptionally efficient in terms of performance and code size. When used effectively, the performance achieved is comparable to the best hand-written JavaScript. This makes GWT a viable option for porting Java libraries to the web.

This highlights another compelling use case for GWT. The Java ecosystem boasts a rich collection of high-quality libraries that lack readily available JavaScript counterparts. GWT’s compiler can be employed to adapt these libraries for web use, enabling developers to combine libraries from both Java and JavaScript and run them within the browser.

This approach is demonstrated in the development of PicShare, which showcases the porting of several Java libraries not typically considered for web use (such as NyARToolkit) to the browser using GWT. By integrating these libraries with web APIs like WebRTC and WebGL, it becomes possible to create fully web-based Augmented Reality tools. This project was presented at the 2015 GWT.create conference last January I was proud to present PicShare.

Behind the Scenes: Transforming Java into JavaScript

Despite its complexity, the GWT Toolkit is surprisingly accessible, thanks to a user-friendly surprisingly easy-to-use integration with Eclipse.

Creating a simple application with GWT is relatively straightforward for anyone familiar with Java development. However, understanding its inner workings requires a closer look at its key components:

- Java to JavaScript Transpiler

- Emulated Java Runtime Environment

- Interoperability Layer

GWT’s Optimizing Compiler

While a detailed explanation of the compiler’s inner workings can quickly become highly technical, some fundamental concepts are worth exploring.

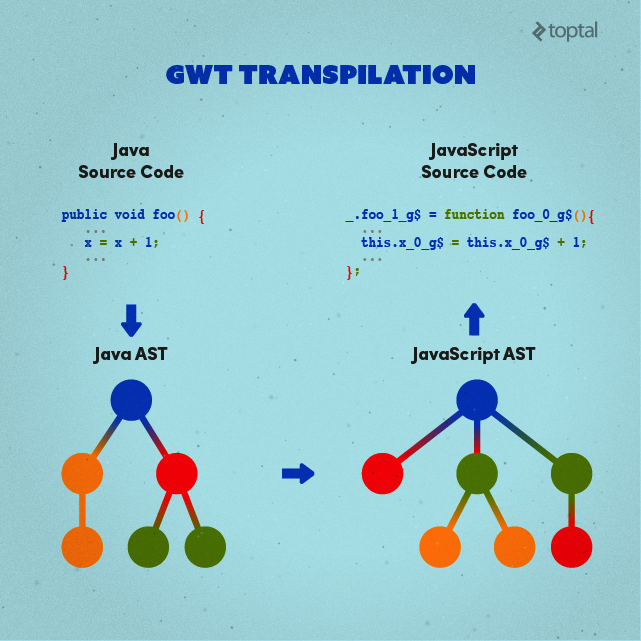

GWT compiles Java into JavaScript through source code translation, also known as transpilation. Instead of relying on a Java Virtual Machine written in JavaScript to execute Java bytecode (as seen in Doppio), GWT takes a different approach.

In GWT, the Java code is first parsed into an abstract syntax tree (AST) representing the code’s structure. This AST is then mapped to an equivalent and optimized JavaScript AST, which is finally converted back into JavaScript code.

While discussing the advantages and disadvantages of transpilation is beyond the scope of this article, it is worth noting that GWT leverages the JavaScript interpreter’s garbage collection and other native browser features through this method.

Naturally, there are challenges. For instance, JavaScript’s single numeric type cannot accommodate Java’s 64-bit long integer type, requiring special handling by the compiler. Additionally, Java’s static typing has no direct equivalent in JavaScript, necessitating careful consideration to maintain the equivalence of operations like typecasting after transpilation.

However, transpilation offers a significant advantage: GWT can perform optimizations for both size and performance at both the Java and JavaScript levels. The generated JavaScript code can be further optimized in the deployment pipeline. A common practice, now integrated into the standard GWT distribution, involves using the specialized JavaScript-to-JavaScript Closure Compiler (another valuable tool from Google) to optimize the transpiler’s JavaScript output.

The most comprehensive description of the GWT compiler can be found in this slide deck and the original talk that it comes from. These resources delve into advanced features such as GWT’s ability to perform code splitting, generating multiple independent script files for individual loading by the browser.

The Emulated JRE

The Java-to-JavaScript compiler would be incomplete without an implementation of the Java Runtime Environment (JRE). The JRE provides the essential libraries relied upon by most Java applications. Without core functionalities like Collections or String methods, working with Java would be impractical, and porting these libraries is an immense task. GWT addresses this with its Emulated JRE.

Rather than a complete re-implementation of the Java JRE, the Emulated JRE offers a carefully chosen subset of classes and methods suitable for client-side use. The functionalities present in the Java JRE but absent from the Emulated JRE fall into three categories:

Features impossible to port client-side. For instance,

java.lang.Threadorjava.io.Filecannot be implemented in a browser with the same semantics as in Java due to the single-threaded nature of browser pages and their lack of direct filesystem access.Features that could be implemented but are omitted due to concerns about code size, performance, or dependencies. For example, Java reflection (

java.lang.reflect) is excluded because it would necessitate the transpiler to retain class information for each type, significantly increasing the compiled JavaScript’s size.Features that haven’t been implemented due to a lack of community interest.

If the Emulated JRE doesn’t meet specific requirements, GWT provides the flexibility to create custom implementations. This powerful mechanism, accessible through the <super-source> tag, proves invaluable when adapting external libraries that rely on JRE components not included in the emulation.

While providing a complete implementation of certain JRE parts might be overly complex or even impossible, custom implementations may not strictly adhere to Java’s JRE semantics for specific tasks, even if they work in particular cases. However, when contributing back to the project, it’s crucial to ensure that any Emulated JRE class implementation adheres strictly to the original Java JRE semantics. This consistency guarantees that anyone can recompile Java code into JavaScript and expect predictable results. Thoroughly testing code before contributing it back to the community is essential.

Interoperability Layer

For building real-world web applications, GWT needs to seamlessly interact with the underlying platform: the browser and the DOM.

From the outset, GWT has facilitated this interaction through its JavaScript Native Interface (JSNI), simplifying access to in-browser APIs. For example, GWT’s compiler-specific syntax allows writing Java code like this:

| |

This allows developers to implement the method body in JavaScript and even wrap JavaScript objects in a [JavaScriptObject (JSO)](http://www.gwtproject.org/javadoc/latest/com/google/gwt/core/client/JavaScriptObject.html#JavaScriptObject() for access within Java code.

UI composition is a prime example of this layer’s significance. Traditionally, Java has relied on the Widgets toolkit for building UI elements, utilizing the Java Native Interface to interact with the operating system’s windowing and input systems. GWT’s interoperability layer replicates this functionality within the browser, ensuring that traditional Widgets work seamlessly.

However, native front-end frameworks have advanced rapidly, offering significant advantages over GWT’s Widgets. As these frameworks become more sophisticated, attempts to implement them using JSNI have exposed limitations in the interoperability layer’s architecture. In version 2.7, GWT introduced JsInterop, a new annotation-based approach for seamless integration between GWT classes and JavaScript. This eliminates the need for JSNI methods or JSO classes, allowing developers to work with native JavaScript classes as if they were Java classes using annotations like @JSType or @JSProperty.

While the full specification of JsInterop is still under development and the latest updates require compiling GWT from its source repository, it’s clear that this approach is crucial for GWT to keep pace with the evolving web.

One project leveraging JsInterop is the recently released gwt-polymer-elements, which provides GWT access to the Iron and Paper elements from Polymer. What’s interesting is that the project uses gwt-api-generator to automatically generate most of the interfaces by analyzing the Polymer library and JSDoc annotations, ensuring easy maintenance and synchronization of the bindings.

Conclusion

The advancements in the compiler, the interoperability layer, and the performance and size of the generated code over the past two years clearly demonstrate that GWT is not just another web development tool. It’s on track to become a key toolkit for developing large-scale, complex web applications and a compelling choice for building impressive, simpler apps.

As a developer and consultant, I use GWT daily. What excites me most about GWT is its ability to push the boundaries of what’s possible in browsers and showcase the potential of modern web applications to rival desktop applications in power and functionality.

With a highly active community constantly proposing new libraries, projects, and applications built on GWT, the toolkit continues to evolve rapidly. For those in the region, the community-driven GWTcon2015 conference in Florence on November 11th offers a fantastic opportunity to connect with core developers and explore the possibilities of contributing to this exceptional toolkit.