In the Java world, certain tools and libraries have become indispensable to me. Before Java 8, dependencies like Google Guava and Joda Time were practically ubiquitous in my projects, no matter the specific domain.

While not your typical library or framework, Lombok has also earned a permanent spot in my project builds. Despite its maturity and long existence since its 2009 release, Lombok still feels somewhat underappreciated, considering its remarkable ability to streamline Java’s inherent verbosity.

This post delves into the features that make Lombok such a valuable asset in a Java developer’s toolkit.

Java’s strengths extend beyond the exceptional JVM. It’s a mature and efficient language, boasting a vast and active community and ecosystem.

However, Java’s design choices and inherent quirks sometimes lead to verbosity. Certain constructs and class patterns, often essential for Java developers, contribute to code that’s lengthy, primarily serving to satisfy constraints or framework conventions rather than adding substantial value.

This is where Lombok steps in, dramatically reducing the “boilerplate” code we need to write. The creators of Lombok are clearly brilliant minds with a sense of humor—their this intro at a previous conference is not to be missed!

Let’s explore how Lombok achieves this and look at some practical examples.

Lombok: Under the Hood

Lombok functions as an annotation processor, essentially injecting code into your classes during compilation. Annotation processing was introduced in Java 5, allowing developers to include annotation processors (either custom-built or from third-party dependencies like Lombok) in the build classpath. During compilation, when the compiler encounters an annotation, it queries the classpath, effectively asking if any processors are interested in handling it. If a processor “raises its hand,” the compiler passes control and compilation context to it for processing.

While common use cases for annotation processors involve generating new source files or performing compile-time checks, Lombok takes a different route. It modifies the compiler’s internal data structures, specifically the abstract syntax tree (AST), which represent the code. This indirect manipulation of the AST ultimately affects the final bytecode generation.

This unconventional and rather intrusive approach has sometimes led to Lombok being labeled as a “hack.” While there’s some truth to this characterization, I prefer to view it as a “clever, technically ingenious, and innovative workaround.”

Admittedly, some developers avoid Lombok for this reason. However, my experience has shown that the productivity gains far outweigh these concerns. I’ve been using it confidently in production environments for years.

Two key reasons solidify my appreciation for Lombok:

- Clean and Concise Code: Lombok helps me write code that is clear, concise, and focused. While opinions may vary, I find Lombok-annotated classes to be highly expressive and intention-revealing.

- Rapid Prototyping: When starting a project, I often begin with rudimentary classes, iteratively refining them as my understanding of the domain model evolves. Lombok accelerates this process by eliminating the need to constantly adjust generated boilerplate code.

Bean Pattern and Common Object Methods

A significant portion of Java’s tools and frameworks rely on the Bean Pattern. These serializable classes typically have a default no-argument constructor (and potentially others) and use getters and setters, often backed by private fields, to expose their state. We encounter them frequently when working with JPA or serialization frameworks like JAXB or Jackson.

Imagine a User bean with up to five attributes (properties). We want an additional constructor for all attributes, a meaningful string representation, and equality/hashing based on the email field:

| |

For the sake of brevity, I’ve replaced the actual method implementations with comments indicating the method names and line counts. The actual boilerplate code would have constituted over 90% of the class!

Furthermore, any changes to the attributes (e.g., renaming email to emailAddress or changing registrationTs from Instant to Date) would necessitate tedious modifications to getters, setters, constructors, and more—a time-consuming endeavor for code that doesn’t directly contribute to business logic.

Let’s see how Lombok streamlines this:

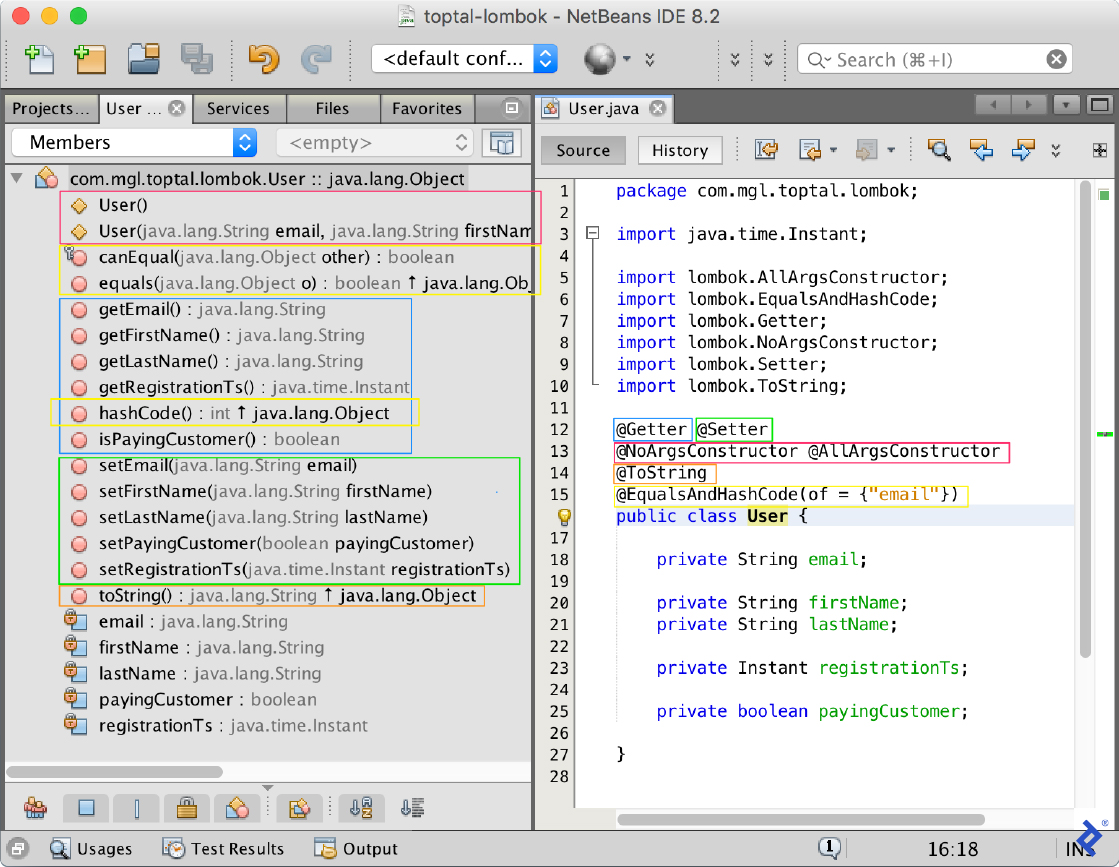

| |

With the addition of a few lombok.* annotations, we’ve achieved the desired outcome. This is all the code we need to write! Lombok takes care of generating everything else during compilation (as shown in the IDE screenshot below).

Notice that the NetBeans inspector (this applies to other IDEs as well) recognizes the compiled bytecode, including Lombok’s contributions. Here’s a breakdown:

@Getterand@Setterat the class level instruct Lombok to generate getters and setters for all attributes. Annotating individual fields allows for selective generation.@NoArgsConstructorprovides a default empty constructor for bean compliance, while@AllArgsConstructorgenerates a constructor accepting all attributes.@ToStringauto-generates a convenienttoString()method, displaying all class attributes with their names by default.@EqualsAndHashCode, parameterized with the relevant field (emailin this case), definesequals()andhashCode()based on the email field.

Customizing Lombok Annotations

Let’s customize Lombok’s behavior using the same User example:

- Constructor Visibility: We’ll restrict the visibility of the default constructor to

AccessLevel.PACKAGEusing@NoArgsConstructor(access = AccessLevel.PACKAGE), encouraging the use of the constructor that takes all fields. - Null Safety: To prevent null values from being assigned to fields, we’ll annotate them with

@NonNull. Lombok will generate null checks within the constructor and setters, throwingNullPointerExceptionas needed. - Excluding Fields from

toString(): For security reasons, we’ll exclude thepasswordattribute from the generatedtoString()method using@ToString(exclude = "password"). - Restricting Mutability: While we’ll expose state publicly via getters using

@Getter, we’ll limit mutability from outside the class by setting@SettertoAccessLevel.PROTECTED. - Custom Logic in Setters: We can override Lombok’s generated methods with our own implementations. For instance, to enforce constraints on the

emailfield, we can manually implement thesetEmail()method.

Here’s the updated User class:

| |

Note that some annotations use plain strings for class attribute names. Lombok provides safety by throwing compile-time errors if we mistype or reference non-existent fields.

As mentioned earlier, if a method or constructor is manually implemented, Lombok will recognize and skip its generation, ensuring flexibility.

Immutable Data Structures

Creating immutable data structures, often referred to as “value types,” is another area where Lombok shines. While some languages have native support for immutability, there’s ongoing work like a proposal to incorporate it into future Java versions.

Let’s consider modeling a response to a user login action (LoginResponse). This object would be instantiated and returned to other application layers (e.g., serialized as JSON in an HTTP response) and wouldn’t require mutability. Lombok allows us to represent this concisely:

| |

Key points:

@RequiredArgsConstructor: Generates a constructor for all final fields not explicitly initialized.@Wither: Facilitates creating modified copies of immutable objects. In this case,@WitherontokenExpiryTsgenerates awithTokenExpiryTs(Instant tokenExpiryTs)method that returns a newLoginResponsewith all values identical to the original instance, except for the updatedtokenExpiryTs. Placing@Witheron the class declaration would generate with-methods for all fields.

@Data and @Value Shorthands

Recognizing the prevalence of these patterns, Lombok offers convenient shortcuts:

@Data: Annotating a class with@Datais equivalent to using@Getter,@Setter,@ToString,@EqualsAndHashCode, and@RequiredArgsConstructor.@Value: This annotation transforms your class into an immutable (and final) one, similar to using the combination mentioned above for@Data.

Builder Pattern

As classes grow, managing constructors with numerous arguments can become unwieldy. Let’s revisit our User example. The constructor now requires up to six arguments, and we might need to set default values for lastName and payingCustomer.

Lombok’s @Builder feature provides an elegant solution using the Builder Pattern. Let’s add it to our User class:

| |

We can now effortlessly create new User instances:

| |

The Builder Pattern becomes increasingly valuable as the complexity of our classes increases.

Delegation and Composition

Java’s verbosity becomes apparent when adhering to the principle of “favor composition over inheritance” and implementing composition. Manually writing delegating methods can be tedious.

Lombok’s @Delegate offers a solution. Let’s introduce a new concept of ContactInformation, which our User class will possess, and other classes might need as well. We’ll represent this with an interface:

| |

Next, we’ll create a ContactInformation class using Lombok:

| |

Finally, we’ll refactor our User class to include ContactInformation, leveraging Lombok to generate the necessary delegating methods to fulfill the interface contract:

| |

Observe that we didn’t need to implement the methods from HasContactInformation. Lombok handles this, delegating calls to our ContactInformation instance.

We’ve also prevented external access to the delegated instance by using @Getter(AccessLevel.NONE), effectively suppressing getter generation for it.

Checked Exceptions

Java’s distinction between checked and unchecked exceptions can sometimes lead to overly verbose code. controversy and criticism arises when exception handling, particularly with APIs throwing checked exceptions, forces us to either catch them or propagate them, potentially cascading this burden to callers.

Consider this scenario:

| |

This pattern is all too familiar. While confident that the URL is valid, the checked exception thrown by the URL constructor forces us to either catch it or declare our method as throwing it, perpetuating the issue. Wrapping checked exceptions in RuntimeException is a common practice, but this approach can become unwieldy as the number of checked exceptions increases.

Lombok’s @SneakyThrows annotation provides relief. It wraps any checked exceptions that might be thrown within a method into an unchecked exception, simplifying our code:

| |

Logging

Adding logger instances to classes is a standard practice: (SLF4J example)

| |

Lombok offers a convenient annotation that generates a logger instance with a customizable name (defaulting to “log”) and supports popular logging frameworks. Here’s an SLF4J-based example:

| |

Annotating Generated Code

While Lombok generates code for us, it doesn’t restrict our ability to annotate that generated code. We can guide Lombok on how to annotate generated elements using a specific notation.

Let’s look at an example involving dependency injection. Our UserService uses constructor injection to obtain references to UserRepository and UserApiClient.

| |

This example illustrates how to annotate a generated constructor. Lombok extends this capability to generated methods and parameters as well.

Exploring Further

This post highlighted the Lombok features I’ve found most beneficial. However, Lombok offers a wide range of additional features and customizations.

The Lombok’s documentation is an invaluable resource, providing comprehensive explanations and examples for each annotation. I encourage you to delve deeper into Lombok’s documentation.

The project site also outlines how to integrate Lombok with various programming environments. Support for popular IDEs like Eclipse, NetBeans, and IntelliJ ensures a seamless experience. I personally use Lombok without issues across these IDEs on a project-by-project basis.

Delombok: Reverting to Source

Delombok is a handy tool within the Lombok ecosystem. It generates Java source code from Lombok-annotated code, replicating the behavior of the Lombok-generated bytecode.

This is an excellent option for teams hesitant about committing to Lombok. It allows you to experiment with Lombok without vendor lock-in. If needed, you can use delombok to generate the equivalent source code, eliminating the Lombok dependency.

Delombok is also invaluable for understanding Lombok’s inner workings. Integrating it into your build process is straightforward.

Alternatives

The Java landscape offers various tools that leverage annotation processors for compile-time code enhancement, such as Immutables and Google Auto Value. These tools often overlap with Lombok in terms of functionality. I have a particular fondness for Immutables and have used it in several projects.

It’s also worth mentioning “bytecode enhancing” tools like Byte Buddy and Javassist. These tools typically operate at runtime and fall outside the scope of this post.

Concise and Maintainable Java

Modern JVM languages like Groovy, Scala, and Kotlin provide more expressive and concise syntax. However, if you’re working within a Java-only codebase, Lombok proves to be an invaluable tool for writing cleaner, more maintainable, and more expressive Java code.