I frequently work with custom full-screen layouts, almost every day. These layouts typically involve a significant amount of interaction and animation. The UI often demands more than just using a pre-built plugin solution with minor adjustments, whether it’s a time-based intricate timeline of transitions or a scroll-driven series of user interactions. However, I’ve observed many JavaScript developers gravitating towards their preferred slider JS plugin to simplify their work, even when the task might not require all the features a particular plugin offers.

Disclaimer: Naturally, there are advantages to using one of the many available plugins. You’ll gain access to a range of options that you can customize without extensive coding. Furthermore, the majority of plugin developers optimize their code, ensuring cross-browser and cross-platform compatibility, among other benefits. Nevertheless, you end up including a full-fledged library in your project for potentially just one or two features it provides. While I’m not suggesting that using third-party plugins is inherently wrong (I utilize them daily in my projects), it’s generally wise to weigh the pros and cons of each approach as a good coding practice. opting to build your own solution requires more coding expertise and a clear understanding of your objectives. However, ultimately, you should end up with a code snippet that performs a specific function exactly as you intend it to.

This article aims to demonstrate a CSS/JS-only method for crafting a full-screen, scroll-activated slider layout featuring custom content animation. In this streamlined approach, we’ll delve into the fundamental HTML structure you’d anticipate from a CMS backend, contemporary CSS (SCSS) layout techniques, and vanilla JavaScript coding for comprehensive interactivity. This bare-bones concept can be effortlessly expanded into a more extensive plugin and/or utilized in various applications without any core dependencies.

The design we’ll be replicating is a minimalist architect portfolio showcase featuring project images and titles. The complete slider with CSS animations will resemble this:

You can explore the demo here and find additional details in my Github repo.

HTML Overview

Here’s the basic HTML we’ll be working with:

| |

Our primary container is a div with the ID hero-slider. The internal layout is segmented into sections:

- Logo (static)

- Slideshow (our main focus)

- Info (static)

- Slider navigation (indicates active slide and total slide count)

Let’s concentrate on the slideshow section, as it’s our primary interest in this article. Within it, we have two components: _main_ and _aux_. The main div houses featured images, while aux holds image titles. The structure of each slide within these containers is fairly simple.

In the main holder, we have an image slide:

| |

We’ll utilize the index data attribute to monitor our position within the slideshow. The abs-mask div will create an engaging transition effect, and the slide-image div contains the specific featured image. Images are rendered inline as if directly from a CMS, set by the end-user.

Similarly, for title slides within the aux holder:

| |

Each title is an H2 tag with a corresponding data attribute and a link to its respective project page.

The remaining HTML is straightforward. We have a logo at the top, static info about the current page and some descriptions, and a slider indicator displaying the current/total slides.

CSS Overview

The source CSS is written in SCSS, a CSS preprocessor that compiles into regular, browser-interpretable CSS. SCSS offers the advantage of using variables, nested selection, mixins, and other valuable features but requires compilation into CSS for browser compatibility. For this tutorial, I’ve used Scout-App to handle compilation, aiming for minimal tooling.

I’ve employed flexbox for the basic side-by-side layout, placing the slideshow on one side and the info section on the other.

| |

Focusing on the slideshow’s positioning:

| |

The main full-page slider is set to absolute positioning, with background images covering the entire area using background-size: cover. For contrast against slide titles, an absolute pseudo-element acts as an overlay. The aux slider, containing slide titles, is positioned at the bottom of the screen, layered atop the images.

Since only one slide is visible at a time, each title is also positioned absolutely. The holder size is calculated using JS to prevent cut-offs (more on this later). Here, you can observe the use of SCSS’s extend feature:

| |

Due to the frequent use of absolute positioning, this CSS is placed in an extend for easy access across various selectors. An “outlined” mixin is created for a DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) approach when styling titles and the main slider title.

| |

The static layout is uncomplicated, but there’s a noteworthy method for positioning text vertically instead of its usual flow:

| |

Pay attention to the transform-origin property, which I find underutilized in such layouts. This element is positioned with its anchor in the upper-left corner, setting the rotation point and allowing text to flow downwards continuously without encountering issues on different screen sizes.

Now, let’s examine a more compelling aspect of the CSS slider—the initial loading animation:

This synchronized animation is typically achieved using libraries like GSAP, known for its excellent rendering, ease of use, and timeline functionality, allowing developers to programmatically chain element transitions.

However, for this pure CSS/JS example, I’ve opted for a rudimentary approach. Each element has a default starting position—hidden by transform or opacity—and is revealed upon slider load, triggered by our JavaScript. All transition properties are meticulously adjusted to ensure a smooth, captivating flow, with each transition seamlessly leading into the next for a visually pleasing experience.

| |

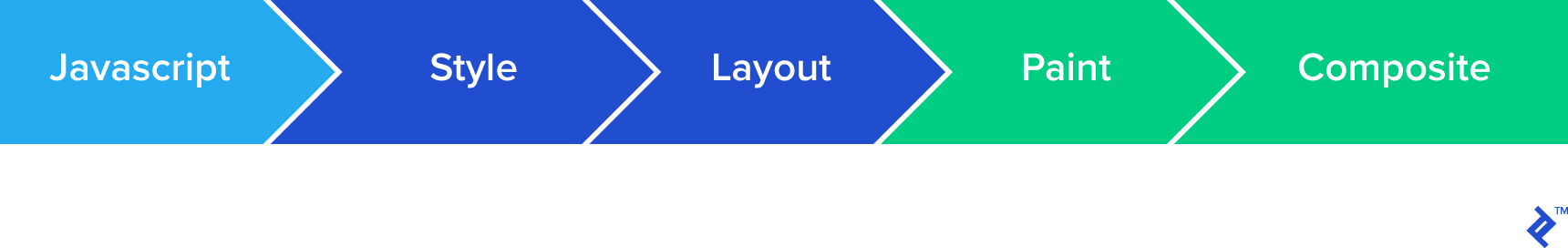

One crucial takeaway is the use of the transform property. When manipulating HTML element positions, whether through transitions or animations, using transform is recommended. Many developers resort to margin, padding, or offsets like top and left, which don’t yield optimal rendering results.

For a deeper dive into using CSS for interactive behavior, I highly recommend following article.

Written by Paul Lewis, a Chrome engineer, this resource extensively covers pixel rendering in web development, encompassing both CSS and JavaScript.

JavaScript Overview and Full Page Slider Logic

The JavaScript slider animation file comprises two functions:

heroSlider: Manages all slider functionality.utils: Contains several reusable utility functions, each commented for context if you wish to repurpose them.

The main function has two branches: init and resize, accessible through the main function’s return value and invoked as needed. init initializes the main function on window load, while resize is triggered on window resize to recalculate the title slider’s size, accounting for potential font size variations.

The heroSlider function features a slider object holding all necessary data and selectors:

| |

This approach can be adapted for frameworks like React by storing data in state or using hooks. For clarity, let’s break down each key-value pair:

- The first four properties reference the manipulated DOM elements.

handlestarts and stops autoplay.idleprevents forced scrolling during slide transitions.activeIndextracks the active slide.intervalsets the autoplay interval.

Upon initialization, two functions are invoked:

| |

setHeight utilizes a utility function to dynamically set the aux slider’s height based on the largest title, ensuring proper sizing and preventing cut-offs in multi-line titles.

loadingAnimation adds a CSS class to the element, triggering the intro CSS transitions:

| |

As the slider indicator is the last element in the CSS transition timeline, we await its transition completion before invoking the start function. Providing an additional object parameter ensures this is triggered only once.

Let’s examine the start function:

| |

Once the layout completes its initial transition (triggered by loadingAnimation), the start function takes over. It initiates autoplay, enables wheel control, detects touch/desktop environments, and waits for the initial title slide transition to apply the appropriate CSS class.

Autoplay

A core feature is autoplay. Let’s analyze the corresponding function:

| |

First, the autoplay flag is set to true, indicating autoplay mode. This flag is crucial for determining whether to reactivate autoplay after user interaction. Next, we reference all slider items (slides) for active class manipulation and calculate total iterations by adding up all items and dividing by two, as we have two synchronized slider layouts (main and aux) but only one “slider” controlling both simultaneously.

The loop function is intriguing. It calls slideChange, providing the slide direction (explained shortly), but the loop function is called multiple times.

If the initial argument is true, the loop function is invoked as a requestAnimationFrame callback. This occurs only on the first load, triggering immediate slide change. requestAnimationFrame executes the provided callback just before the next frame repaint.

To continuously cycle through slides in autoplay mode, we’d typically use setInterval. However, here, we utilize the requestInterval utility function. While setInterval would suffice, requestInterval, based on requestAnimationFrame, offers a more performant approach, ensuring the function is re-triggered only when the browser tab is active.

This concept is explained further in an excellent article on CSS tricks. Note that the function’s return value is assigned to our slider.handle property. This unique ID is used later to cancel autoplay using cancelAnimationFrame.

Slide Change

slideChange, the principal function, handles slide transitions, whether automated or user-triggered. It’s direction-aware, provides looping (seamlessly transitioning from the last to the first slide), and is implemented as follows:

| |

The goal is to determine the active slide using the data-index attribute from the HTML. Let’s break down the steps:

- Set the

slider.idleflag tofalse, signaling a slide change is in progress, disabling wheel and touch interactions. - Reset the previous direction CSS class and determine the new one. The

directionparameter is either “next” (default from autoplay) or provided by user-invoked functions likewheelControlortouchControl. - Based on the direction, calculate the active slide index and apply the corresponding direction CSS class to the slider, determining the transition effect (e.g., right-to-left or left-to-right).

- Reset “state” CSS classes (prev, active) on all slides using a utility function capable of operating on a NodeList. Afterward, only the previous and active slides have these classes reapplied, enabling targeted CSS transitions.

setCurrent(a callback) updates the slider indicator based on theactiveIndex.- Finally, wait for the active image slide’s transition to end before triggering the

waitForIdlecallback, which restarts autoplay if previously interrupted.

User Controls

Two user controls are implemented based on screen size: wheel and touch.

Wheel control:

| |

We listen for the wheel event, and if the slider is idle, determine wheel direction, stop autoplay (if active) using stopAutoplay, and change slides accordingly. The stopAutoplay function simply sets the autoplay flag to false and cancels the interval using the cancelRequestInterval utility function with the appropriate handle:

| |

Similar to wheelControl, touchControl handles touch gestures:

| |

We listen for touchstart and touchmove events, calculate the difference in touch positions, and trigger slideChange with the appropriate direction (“next” for right-to-left swipes, “previous” for left-to-right). Autoplay is stopped in both cases.

This is a basic user gesture implementation. We could enhance it with previous/next buttons triggering slideChange on click or a bulleted list for direct slide navigation using indices.

CSS/JavaScript Slider Wrap-up and Final Thoughts on CSS

There you have it—a pure CSS/JS approach to coding a non-standard slider layout with modern transition effects.

I hope this method provides a useful way of thinking and inspires you to implement similar solutions in your front-end projects, especially when dealing with unconventional designs.

For those interested in the image transition effect:

Recall the slide HTML structure mentioned earlier. Each image slide has a wrapping div with the class abs-mask, which partially hides the visible image using overflow: hidden and an offset opposite to the image’s direction. For example, the previous slide’s code:

| |

The previous slide has a -100% offset on the X-axis, moving it to the left of the current slide. However, the inner abs-mask div is translated 80% to the right, creating a narrower viewport. Combined with the active slide’s larger z-index, this results in a cover effect, where the active image overlaps the previous while simultaneously expanding its visible area by moving the mask, providing a full view.