The increasing prevalence of cloud computing and big data in recent times has led to a surge in the use of distributed systems.

distributed caches, which form the backbone of numerous high-traffic, dynamic websites and web applications, are a prime example of such systems. They often rely on a specific type of distributed hashing that leverages an algorithm known as consistent hashing.

But what exactly is consistent hashing? What purpose does it serve, and why should it matter to you?

This article will delve into the world of consistent hashing. We’ll begin with a refresher on hashing and its fundamental purpose before moving on to distributed hashing and its inherent challenges. This, in turn, will pave the way for a comprehensive understanding of our main topic.

What Is Hashing?

Let’s start by unraveling the concept of “hashing.” Merriam-Webster defines the noun hash as “chopped meat mixed with potatoes and browned,” and the verb as “to chop (as meat and potatoes) into small pieces.” Setting aside the culinary aspect, “hash” essentially means “chop and mix”—the very essence of the technical term.

In essence, a hash function takes a piece of data, typically representing an object of any size, and transforms it into another piece of data, usually an integer. This resulting integer is called a hash code, or simply a hash.

For instance, a hash function designed to hash strings and produce outputs ranging from 0 to 100 might map the string Hello to the number 57, Hasta la vista, baby to 33, and any other possible string to a number within that range. Due to the vast number of possible inputs compared to outputs, multiple strings will inevitably map to the same number, a phenomenon known as a collision. The effectiveness of a hash function lies in its ability to “chop and mix” (hence the term) input data, ensuring that the outputs for different inputs are distributed as evenly as possible across the output range.

Hash functions serve a variety of purposes, each with its own set of desired properties. One type, known as cryptographic hash functions, must adhere to stringent requirements and are primarily employed for security purposes, such as password protection, message integrity and fingerprint verification, and data corruption detection. However, these fall outside the scope of our current discussion.

Beyond cryptography, non-cryptographic hash functions have their own applications, the most prevalent being their use in hash tables, which are of particular interest to us.

Introducing Hash Tables (Hash Maps)

Imagine needing to maintain a list of club members while ensuring the ability to search for any specific member efficiently. One approach would be to store the list in an array (or linked list) and iterate through it during a search until the desired member is found (perhaps based on their name). In the worst-case scenario, this could involve checking all members (if the target member is last or not present), or half of them on average. In terms of computational complexity, this search operation would have a complexity of O(n). While reasonably fast for small lists, it would become progressively slower as the number of members increases.

Can we improve upon this? Let’s assume our club members have unique, sequential IDs that correspond to their joining order.

If searching by ID were acceptable, we could store all members in an array, aligning their positions with their IDs (e.g., a member with ID=10 would occupy index 10 in the array). This would enable direct access to each member without the need for a search, achieving the highest possible efficiency—constant time complexity, denoted as O(1).

However, the scenario of sequential IDs is rather idealistic. What if IDs were large, non-sequential, or random numbers? What if searching by ID wasn’t feasible, and we had to search by name or another field instead? It would be highly advantageous to retain our fast direct access (or something similar) while accommodating arbitrary datasets and less restrictive search criteria.

This is where hash functions come into play. By mapping arbitrary data to an integer, a suitable hash function can effectively mimic the role of our club member ID, albeit with some key differences.

Firstly, good hash functions typically have a wide output range (often the entire range of a 32 or 64-bit integer), making it impractical or impossible to create an array encompassing all possible indices. This would also result in a significant waste of memory. To address this, we can utilize a reasonably sized array (e.g., twice the expected number of elements) and apply a modulo operation on the hash to determine the array index. Thus, the index would be calculated as index = hash(object) mod N, where N represents the array size.

Secondly, object hashes are generally not unique (unless dealing with a fixed dataset and a custom-built perfect hash function, which is beyond the scope of this discussion). Collisions will occur (further amplified by the modulo operation), so simple direct index access won’t suffice. There are various methods to handle this, but a common approach is to associate each array index with a list, often referred to as a bucket, to store all objects sharing that index.

Therefore, we have an array of size N, with each entry pointing to an object bucket. Adding a new object involves calculating its hash modulo N and checking the corresponding bucket at that index. If the object isn’t already present, it’s added to the bucket. Searching for an object follows the same process, but instead of adding, we check if the object exists within the bucket. This structure is called a hash table. Although searches within buckets are linear, a well-dimensioned hash table should have a relatively small number of objects per bucket, resulting in near-constant time access (average complexity of O(N/k), where k is the number of buckets).

When dealing with complex objects, the hash function is typically applied to a specific key rather than the entire object. In our club member example, each object might contain multiple fields (name, age, address, email, phone), but we could choose the email as the key, applying the hash function solely to the email. Moreover, the key doesn’t necessarily have to be part of the object. It’s common to store key/value pairs, where the key is usually a relatively short string, and the value can be any arbitrary data. In such cases, the hash table, or hash map, functions as a dictionary, which is how some high-level programming languages implement objects or associative arrays.

Scaling Out: Distributed Hashing

Having covered the basics of hashing, let’s now explore distributed hashing.

In certain scenarios, it might be necessary or beneficial to partition a hash table across multiple servers. This is often driven by the need to overcome memory limitations imposed by a single computer, allowing for the creation of arbitrarily large hash tables (given sufficient servers).

In this distributed setup, objects (and their keys) are distributed among multiple servers, hence the term “distributed hashing.”

A typical use case for distributed hashing is the implementation of in-memory caches, such as Memcached.

These setups involve a pool of caching servers that store numerous key/value pairs, providing rapid access to data that might otherwise be retrieved from a slower source (or computed). For instance, to alleviate the load on a database server and simultaneously enhance performance, an application can be designed to first attempt data retrieval from the cache servers. Only if the data isn’t found in the cache (a cache miss), does the application resort to querying the database, subsequently caching the retrieved data with an appropriate key for future access.

But how is this distribution achieved? What determines which keys reside on which servers?

The simplest approach is to use the hash modulo the number of servers, calculated as server = hash(key) mod N, where N is the pool size. To store or retrieve a key, the client first computes the hash, applies the modulo N operation, and uses the resulting index to contact the appropriate server (usually via a lookup table of IP addresses). Note that while all clients must use the same hash function for key distribution, this function doesn’t have to be the same as the one used internally by the caching servers.

Let’s illustrate with an example. Suppose we have three servers—A, B, and C—and a set of string keys with their corresponding hashes:

| KEY | HASH | HASH mod 3 |

|---|---|---|

| "john" | 1633428562 | 2 |

| "bill" | 7594634739 | 0 |

| "jane" | 5000799124 | 1 |

| "steve" | 9787173343 | 0 |

| "kate" | 3421657995 | 2 |

If a client wants to retrieve the value for the key john, its hash modulo 3 is 2, directing the request to server C. Assuming the key isn’t found there, the client fetches the data from the source and adds it to the cache. The pool now looks like this:

| A | B | C |

|---|---|---|

| "john" |

Next, another client (or the same one) wants to retrieve the value for the key bill. Its hash modulo 3 is 0, leading it to server A. Again, if the key is missing, the client fetches and caches the data. The updated pool:

| A | B | C |

|---|---|---|

| "bill" | "john" |

After adding the remaining keys, the final distribution becomes:

| A | B | C |

|---|---|---|

| "bill" | "jane" | "john" |

| "steve" | "kate" |

The Rehashing Problem

This straightforward distribution scheme works seamlessly until the number of servers changes. What happens if a server crashes or becomes unavailable? Keys need to be redistributed to compensate for the missing server. The same applies when adding new servers to the pool. However, the main drawback of the modulo distribution scheme is that changing the server count affects most hashes modulo N values, necessitating the relocation of most keys. Consequently, even a single server addition or removal can trigger a global rehashing of keys.

Revisiting our example, if we remove server C, all keys would have to be rehashed using hash modulo 2 instead of hash modulo 3, resulting in the following redistribution:

| KEY | HASH | HASH mod 2 |

|---|---|---|

| "john" | 1633428562 | 0 |

| "bill" | 7594634739 | 1 |

| "jane" | 5000799124 | 0 |

| "steve" | 9787173343 | 1 |

| "kate" | 3421657995 | 1 |

| A | B |

|---|---|

| "john" | "bill" |

| "jane" | "steve" |

| "kate" |

Notice that all key locations have changed, not just those originally residing on server C.

In the context of caching, this mass relocation of keys would render them temporarily inaccessible at their new locations, leading to a surge in cache misses. As a result, the original data source (often a database) would be inundated with requests to retrieve and rehash data, potentially causing performance degradation or even crashes.

The Solution: Consistent Hashing

How can we address this rehashing problem? Ideally, we need a distribution scheme that is independent of the server count, minimizing key relocations when servers are added or removed. Consistent hashing, a remarkably simple yet effective solution, achieves this. It was first introduced in a 1997 academic paper by Karger et al. at MIT (as per Wikipedia).

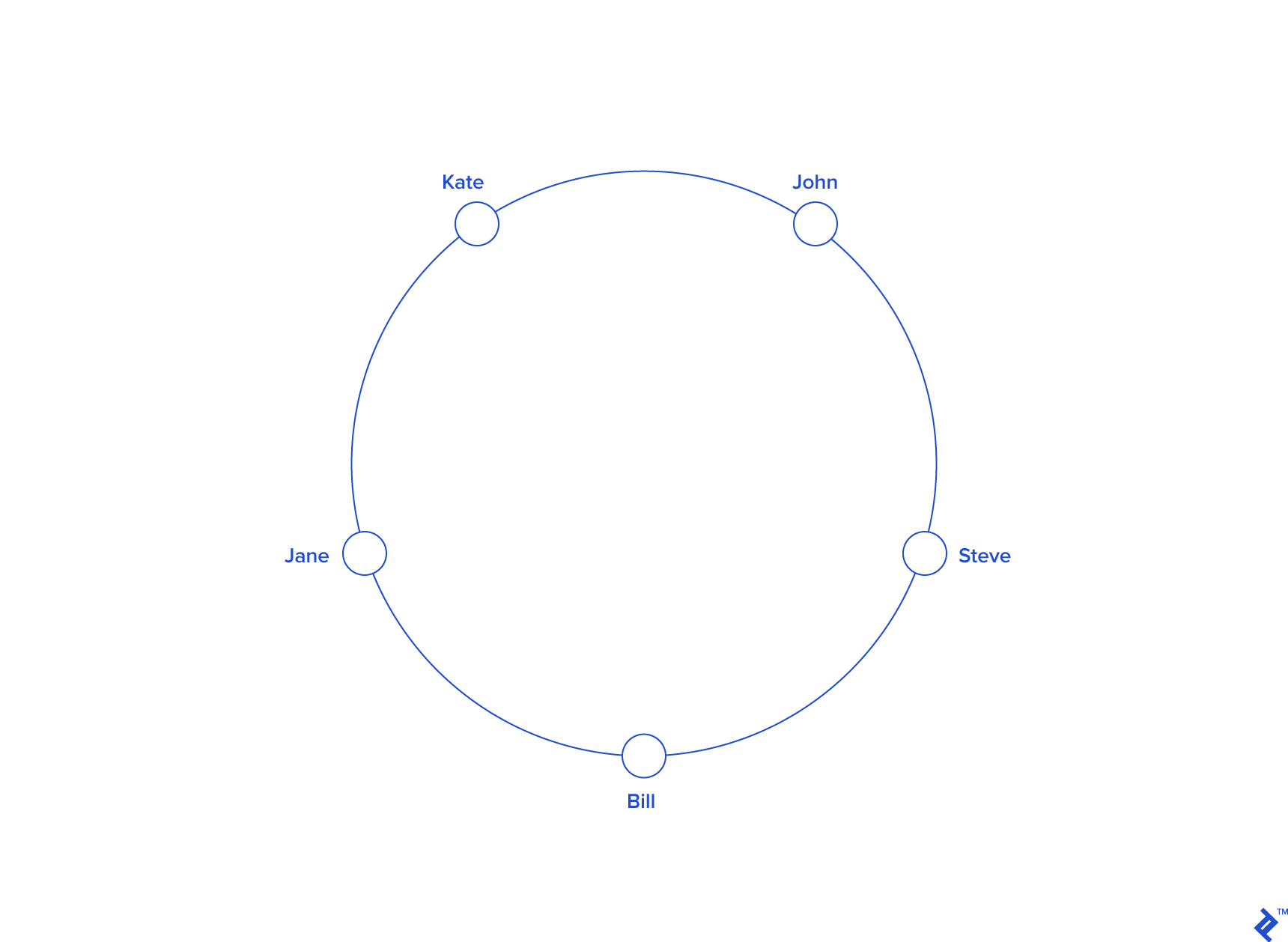

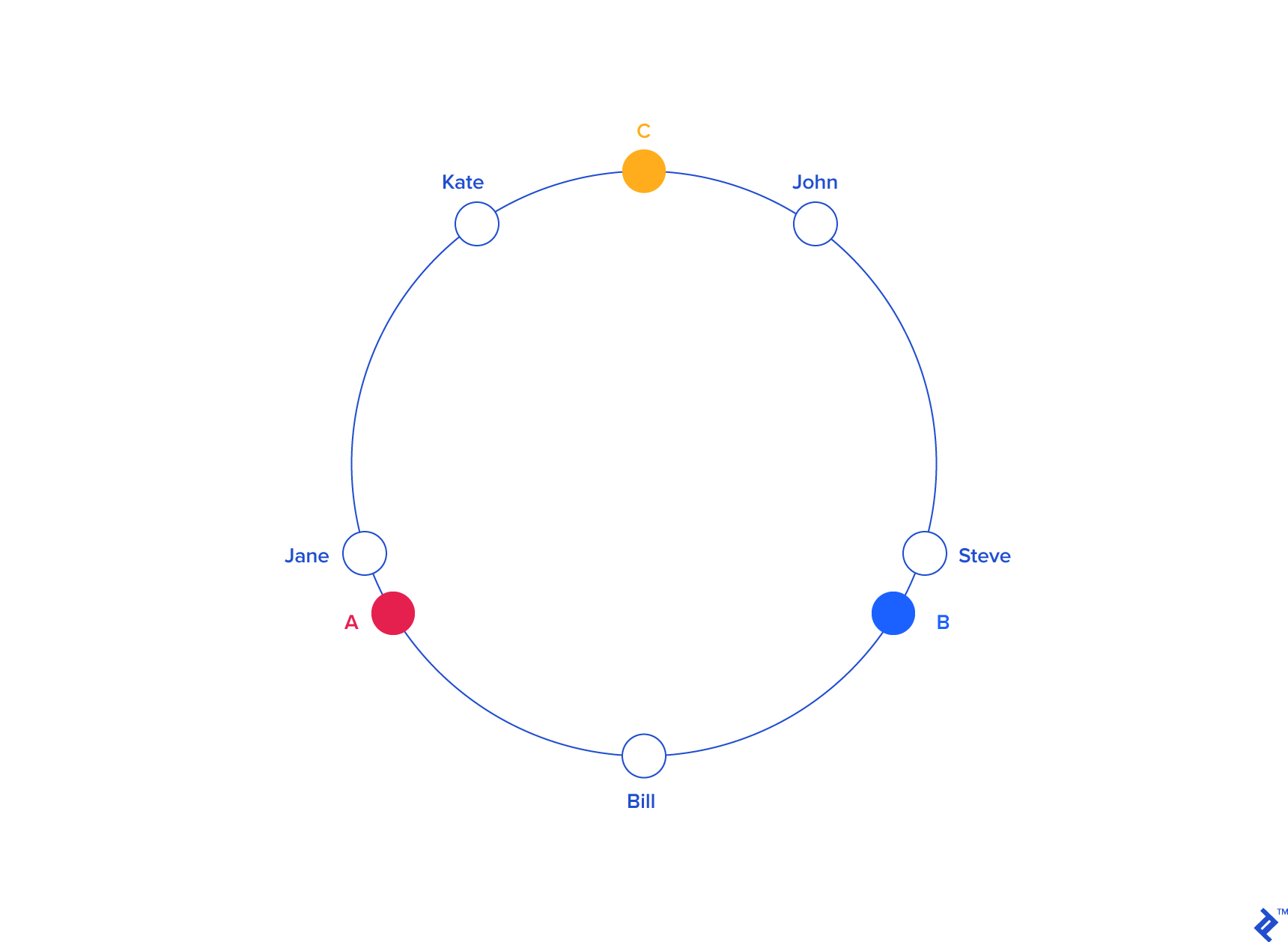

Consistent Hashing tackles the issue of server and object scalability in distributed hash tables. It achieves this by positioning them on an abstract circle known as a hash ring, ensuring minimal disruption when servers or objects are added or removed.

Imagine mapping the entire hash output range onto the circumference of a circle. The minimum hash value (zero) would correspond to an angle of zero, the maximum value (INT_MAX) to 2𝝅 radians (360 degrees), and all other hash values would be linearly distributed in between. This allows us to determine a key’s position on the circle by calculating its hash. For instance, with an INT_MAX of 1010, our previous example keys would be positioned as follows:

| KEY | HASH | ANGLE (DEG) |

|---|---|---|

| "john" | 1633428562 | 58.8 |

| "bill" | 7594634739 | 273.4 |

| "jane" | 5000799124 | 180 |

| "steve" | 9787173343 | 352.3 |

| "kate" | 3421657995 | 123.2 |

Next, we place the servers on the same circle, assigning them pseudo-random angles in a repeatable manner (ensuring all clients agree on server positions). One approach is to hash the server name (or IP address, or ID) to determine its angle, similar to how we handle object keys.

Our example might look like this:

| KEY | HASH | ANGLE (DEG) |

|---|---|---|

| "john" | 1633428562 | 58.8 |

| "bill" | 7594634739 | 273.4 |

| "jane" | 5000799124 | 180 |

| "steve" | 9787173343 | 352.3 |

| "kate" | 3421657995 | 123.2 |

| "A" | 5572014558 | 200.6 |

| "B" | 8077113362 | 290.8 |

| "C" | 2269549488 | 81.7 |

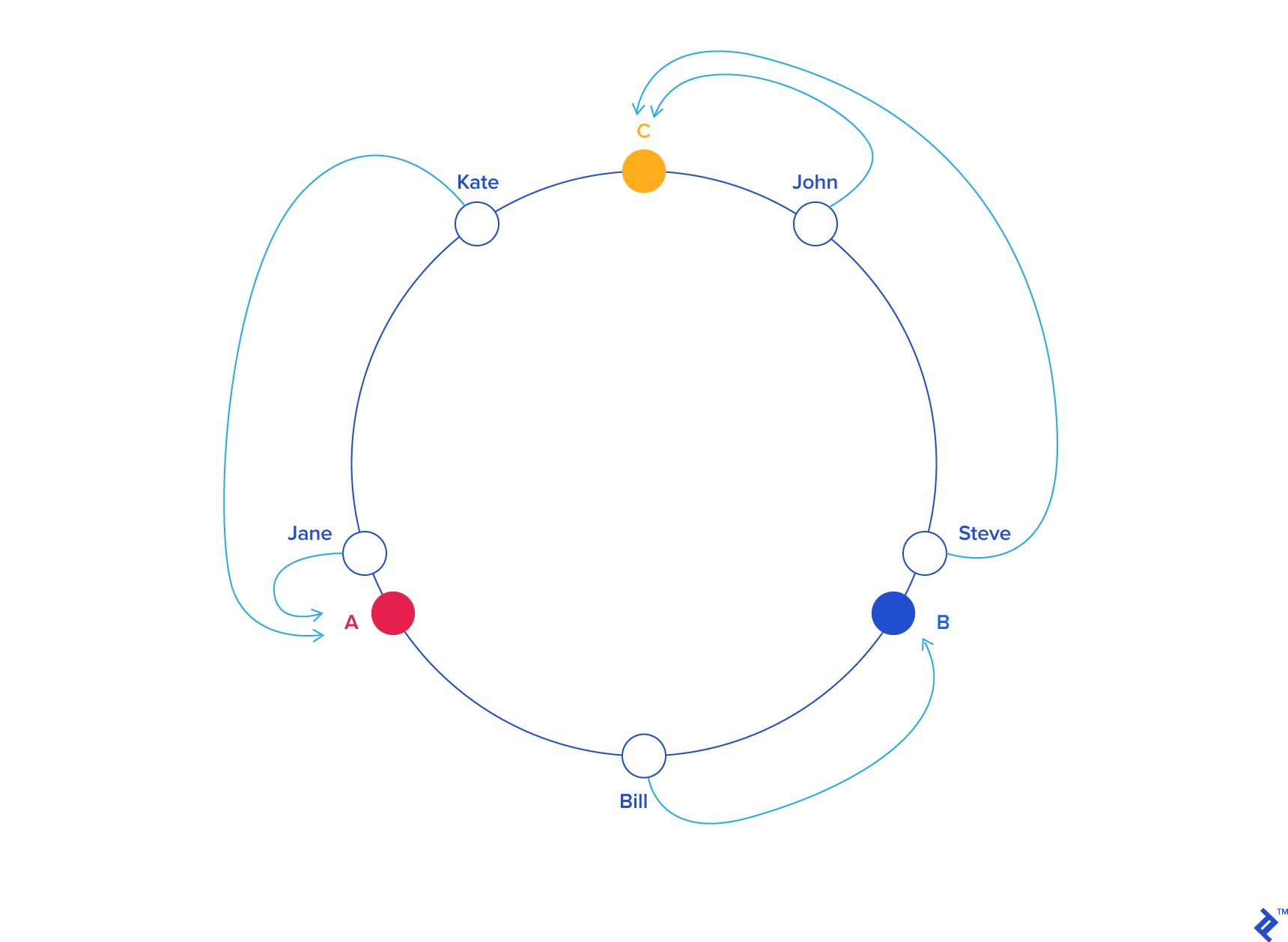

With both object and server keys residing on the same circle, we can establish a simple rule for association: each object key belongs to the server whose key is closest in a counterclockwise direction (or clockwise, depending on the chosen convention). Therefore, to locate the server responsible for a given key, we find the key on the circle and move counterclockwise until encountering a server.

Applying this to our example:

| KEY | HASH | ANGLE (DEG) |

|---|---|---|

| "john" | 1633428562 | 58.7 |

| "C" | 2269549488 | 81.7 |

| "kate" | 3421657995 | 123.1 |

| "jane" | 5000799124 | 180 |

| "A" | 5572014557 | 200.5 |

| "bill" | 7594634739 | 273.4 |

| "B" | 8077113361 | 290.7 |

| "steve" | 787173343 | 352.3 |

| KEY | HASH | ANGLE (DEG) | LABEL | SERVER |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "john" | 1632929716 | 58.7 | "C" | C |

| "kate" | 3421831276 | 123.1 | "A" | A |

| "jane" | 5000648311 | 180 | "A" | A |

| "bill" | 7594873884 | 273.4 | "B" | B |

| "steve" | 9786437450 | 352.3 | "C" | C |

From a programming perspective, this translates to maintaining a sorted list of server values (angles or numbers within a range) and using a binary search to find the first server with a value greater than or equal to the target key’s value. If no such value exists, we wrap around, selecting the first server in the list.

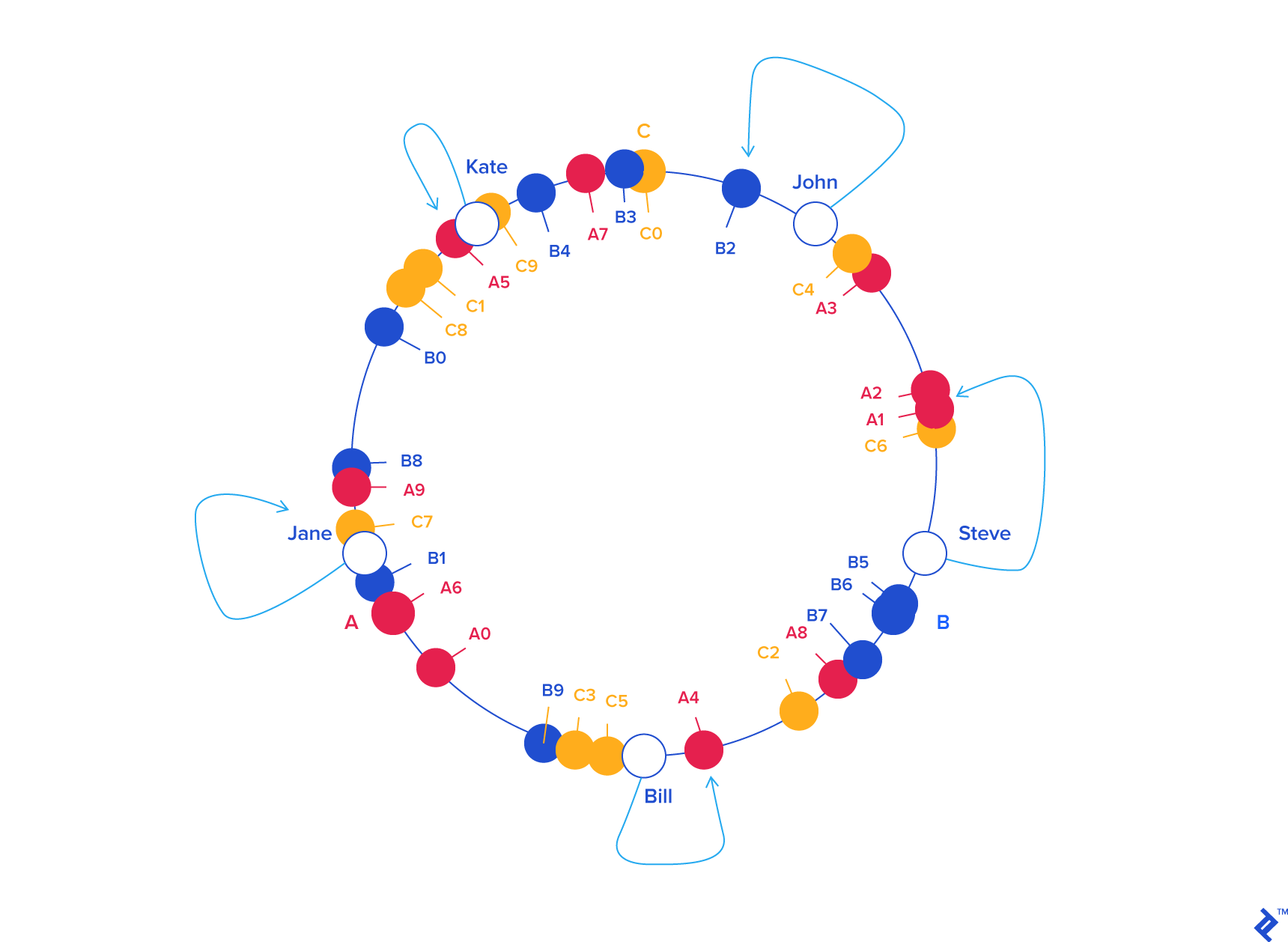

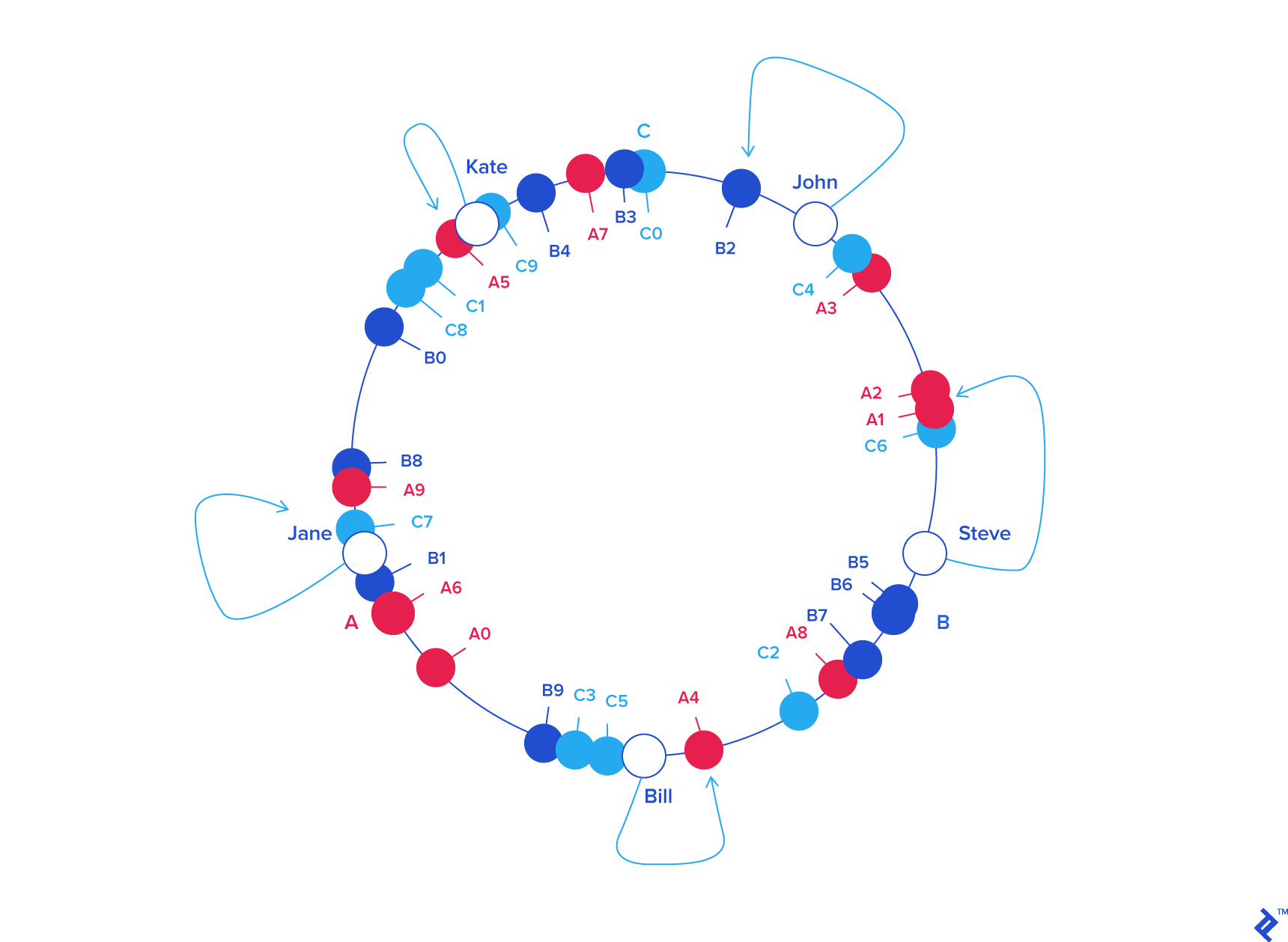

To ensure an even distribution of object keys among servers, we introduce the concept of weight. Instead of a single label (angle), each server receives multiple labels. For instance, instead of A, B, and C, we could have A0 .. A9, B0 .. B9, and C0 .. C9 distributed along the circle. The weight, which determines the number of labels per server, can be adjusted to control the probability of keys being assigned to each server. For example, a server twice as powerful as others could receive twice as many labels, resulting in it holding twice as many objects on average.

Let’s assign an equal weight of 10 to all three servers in our example:

| KEY | HASH | ANGLE (DEG) |

|---|---|---|

| "C6" | 408965526 | 14.7 |

| "A1" | 473914830 | 17 |

| "A2" | 548798874 | 19.7 |

| "A3" | 1466730567 | 52.8 |

| "C4" | 1493080938 | 53.7 |

| "john" | 1633428562 | 58.7 |

| "B2" | 1808009038 | 65 |

| "C0" | 1982701318 | 71.3 |

| "B3" | 2058758486 | 74.1 |

| "A7" | 2162578920 | 77.8 |

| "B4" | 2660265921 | 95.7 |

| "C9" | 3359725419 | 120.9 |

| "kate" | 3421657995 | 123.1 |

| "A5" | 3434972143 | 123.6 |

| "C1" | 3672205973 | 132.1 |

| "C8" | 3750588567 | 135 |

| "B0" | 4049028775 | 145.7 |

| "B8" | 4755525684 | 171.1 |

| "A9" | 4769549830 | 171.7 |

| "jane" | 5000799124 | 180 |

| "C7" | 5014097839 | 180.5 |

| "B1" | 5444659173 | 196 |

| "A6" | 6210502707 | 223.5 |

| "A0" | 6511384141 | 234.4 |

| "B9" | 7292819872 | 262.5 |

| "C3" | 7330467663 | 263.8 |

| "C5" | 7502566333 | 270 |

| "bill" | 7594634739 | 273.4 |

| "A4" | 8047401090 | 289.7 |

| "C2" | 8605012288 | 309.7 |

| "A8" | 8997397092 | 323.9 |

| "B7" | 9038880553 | 325.3 |

| "B5" | 9368225254 | 337.2 |

| "B6" | 9379713761 | 337.6 |

| "steve" | 9787173343 | 352.3 |

| KEY | HASH | ANGLE (DEG) | LABEL | SERVER |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "john" | 1632929716 | 58.7 | "B2" | B |

| "kate" | 3421831276 | 123.1 | "A5" | A |

| "jane" | 5000648311 | 180 | "C7" | C |

| "bill" | 7594873884 | 273.4 | "A4" | A |

| "steve" | 9786437450 | 352.3 | "C6" | C |

Now, what advantage does this circular arrangement offer? Consider removing server C. To reflect this change, we remove labels C0 .. C9 from the circle. Consequently, the object keys adjacent to the removed labels are reassigned to servers A and B, acquiring new labels (Ax and Bx).

The beauty of consistent hashing lies in the fact that object keys originally belonging to servers A and B remain unaffected by the removal of C. Their positions and server assignments remain unchanged:

| KEY | HASH | ANGLE (DEG) |

|---|---|---|

| "A1" | 473914830 | 17 |

| "A2" | 548798874 | 19.7 |

| "A3" | 1466730567 | 52.8 |

| "john" | 1633428562 | 58.7 |

| "B2" | 1808009038 | 65 |

| "B3" | 2058758486 | 74.1 |

| "A7" | 2162578920 | 77.8 |

| "B4" | 2660265921 | 95.7 |

| "kate" | 3421657995 | 123.1 |

| "A5" | 3434972143 | 123.6 |

| "B0" | 4049028775 | 145.7 |

| "B8" | 4755525684 | 171.1 |

| "A9" | 4769549830 | 171.7 |

| "jane" | 5000799124 | 180 |

| "B1" | 5444659173 | 196 |

| "A6" | 6210502707 | 223.5 |

| "A0" | 6511384141 | 234.4 |

| "B9" | 7292819872 | 262.5 |

| "bill" | 7594634739 | 273.4 |

| "A4" | 8047401090 | 289.7 |

| "A8" | 8997397092 | 323.9 |

| "B7" | 9038880553 | 325.3 |

| "B5" | 9368225254 | 337.2 |

| "B6" | 9379713761 | 337.6 |

| "steve" | 9787173343 | 352.3 |

| KEY | HASH | ANGLE (DEG) | LABEL | SERVER |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "john" | 1632929716 | 58.7 | "B2" | B |

| "kate" | 3421831276 | 123.1 | "A5" | A |

| "jane" | 5000648311 | 180 | "B1" | B |

| "bill" | 7594873884 | 273.4 | "A4" | A |

| "steve" | 9786437450 | 352.3 | "A1" | A |

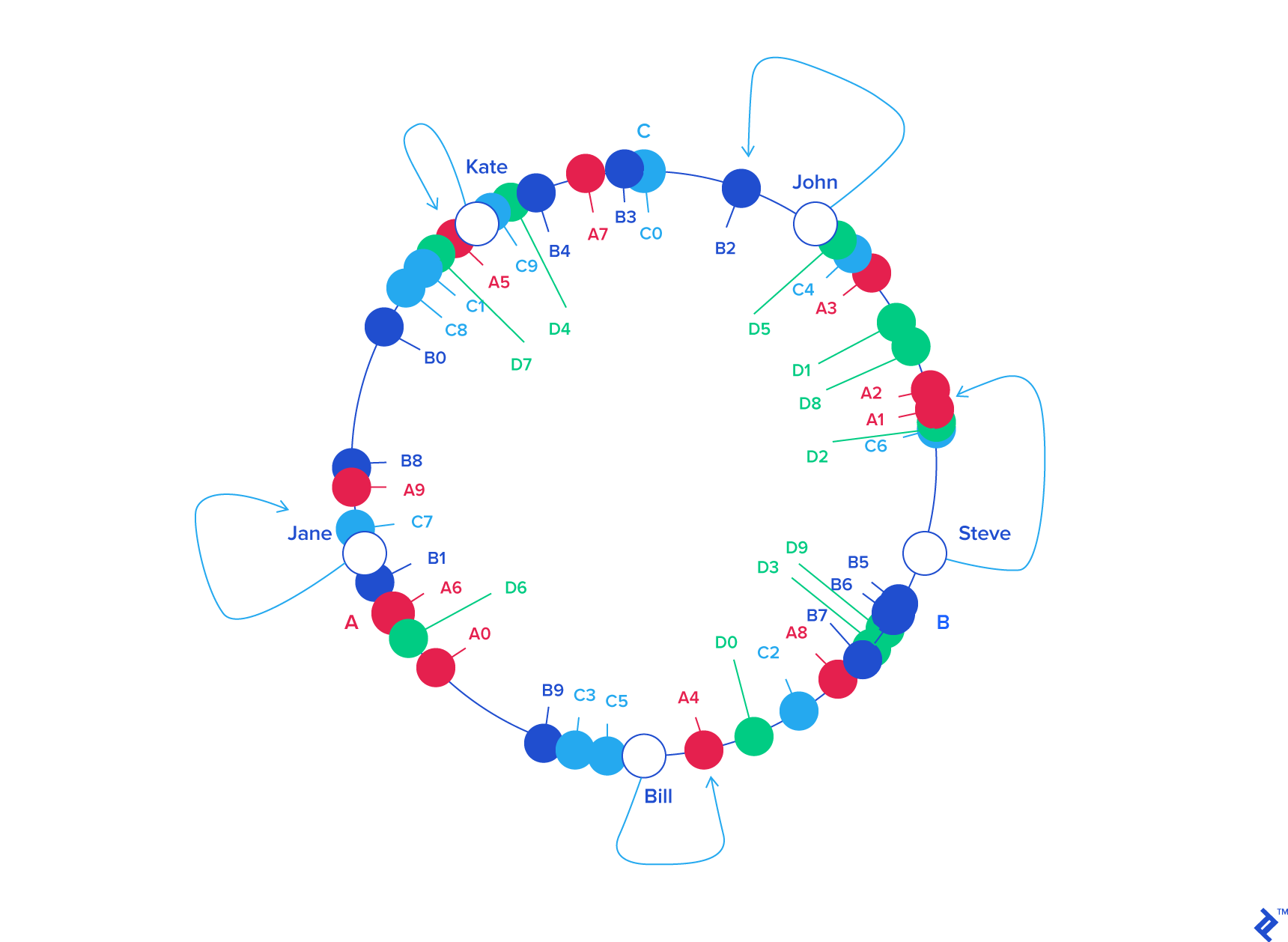

A similar scenario unfolds when adding a new server. Introducing server D (as a replacement for C) involves adding labels D0 .. D9 to the circle. This results in roughly one-third of the existing keys (those originally belonging to A or B) being reassigned to D, while the rest retain their original positions and server assignments:

| KEY | HASH | ANGLE (DEG) |

|---|---|---|

| "D2" | 439890723 | 15.8 |

| "A1" | 473914830 | 17 |

| "A2" | 548798874 | 19.7 |

| "D8" | 796709216 | 28.6 |

| "D1" | 1008580939 | 36.3 |

| "A3" | 1466730567 | 52.8 |

| "D5" | 1587548309 | 57.1 |

| "john" | 1633428562 | 58.7 |

| "B2" | 1808009038 | 65 |

| "B3" | 2058758486 | 74.1 |

| "A7" | 2162578920 | 77.8 |

| "B4" | 2660265921 | 95.7 |

| "D4" | 2909395217 | 104.7 |

| "kate" | 3421657995 | 123.1 |

| "A5" | 3434972143 | 123.6 |

| "D7" | 3567129743 | 128.4 |

| "B0" | 4049028775 | 145.7 |

| "B8" | 4755525684 | 171.1 |

| "A9" | 4769549830 | 171.7 |

| "jane" | 5000799124 | 180 |

| "B1" | 5444659173 | 196 |

| "D6" | 5703092354 | 205.3 |

| "A6" | 6210502707 | 223.5 |

| "A0" | 6511384141 | 234.4 |

| "B9" | 7292819872 | 262.5 |

| "bill" | 7594634739 | 273.4 |

| "A4" | 8047401090 | 289.7 |

| "D0" | 8272587142 | 297.8 |

| "A8" | 8997397092 | 323.9 |

| "B7" | 9038880553 | 325.3 |

| "D3" | 9048608874 | 325.7 |

| "D9" | 9314459653 | 335.3 |

| "B5" | 9368225254 | 337.2 |

| "B6" | 9379713761 | 337.6 |

| "steve" | 9787173343 | 352.3 |

| KEY | HASH | ANGLE (DEG) | LABEL | SERVER |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "john" | 1632929716 | 58.7 | "B2" | B |

| "kate" | 3421831276 | 123.1 | "A5" | A |

| "jane" | 5000648311 | 180 | "B1" | B |

| "bill" | 7594873884 | 273.4 | "A4" | A |

| "steve" | 9786437450 | 352.3 | "D2" | D |

This is how consistent hashing effectively mitigates the rehashing problem.

In general, only k/N keys require remapping, where k represents the number of keys, and N is the number of servers (more specifically, the maximum of the initial and final server counts).

What Next?

When employing distributed caching for performance optimization, changes in the number of caching servers (due to crashes or capacity adjustments) are inevitable. By leveraging consistent hashing for key distribution, we minimize the impact of these changes on the origin servers, as only a small fraction of keys require rehashing. This helps prevent potential downtime or performance degradation.

Various systems, such as Memcached and Redis, offer clients with built-in support for consistent hashing.

Alternatively, the algorithm itself is relatively straightforward to implement in any programming language once the underlying concept is grasped.

For those interested in exploring further, Toptal’s blog offers a wealth of insightful articles on data science.