As applications increase in complexity, maintaining high-quality logs becomes invaluable, serving not only debugging purposes but also providing insights into application issues and performance bottlenecks.

Python’s standard library offers the logging module, equipped with a comprehensive suite of basic logging functionalities. When configured correctly, log messages can provide a wealth of information, including timestamps, log origins, and contextual details like the active process or thread.

However, despite its merits, the Python logging module is often neglected due to its initial setup time. While the official documentation at https://docs.python.org/3/library/logging.html is comprehensive, it might not effectively convey logging best practices or illuminate certain nuances.

This Python logging tutorial is not intended as an exhaustive guide to the module. Instead, it serves as a primer, introducing fundamental logging concepts and highlighting potential pitfalls. The concluding section will present best practices and direct readers to more advanced logging topics.

For the code snippets provided, it’s assumed that the Python logging module is already imported:

| |

Understanding Python Logging Concepts

This section provides an overview of key concepts frequently encountered in the Python logging module.

Log Levels in Python

Log levels reflect the assigned “importance” of a log message. An “error” log should demand higher attention than a “warning” log, while a “debug” log primarily aids in debugging efforts.

Python defines six log levels, each associated with an integer representing its severity: NOTSET=0, DEBUG=10, INFO=20, WARN=30, ERROR=40, and CRITICAL=50.

Most levels are self-explanatory (DEBUG < INFO < WARN). The exception is NOTSET, the specifics of which will be addressed later.

Formatting Python Logs

Log formatters enhance log messages by appending contextual information. This might include timestamps, log origins (file, line number, method, etc.), and additional context like thread and process IDs, particularly helpful when debugging multithreaded applications.

For instance, a simple “hello world” log message:

| |

when processed by a log formatter, might appear as:

| |

Log Handlers in Python

Log handlers are responsible for the actual writing or display of log messages. They direct logs to various destinations: the console (via StreamHandler), files (via FileHandler), or even email via SMTPHandler.

Each log handler has two key attributes:

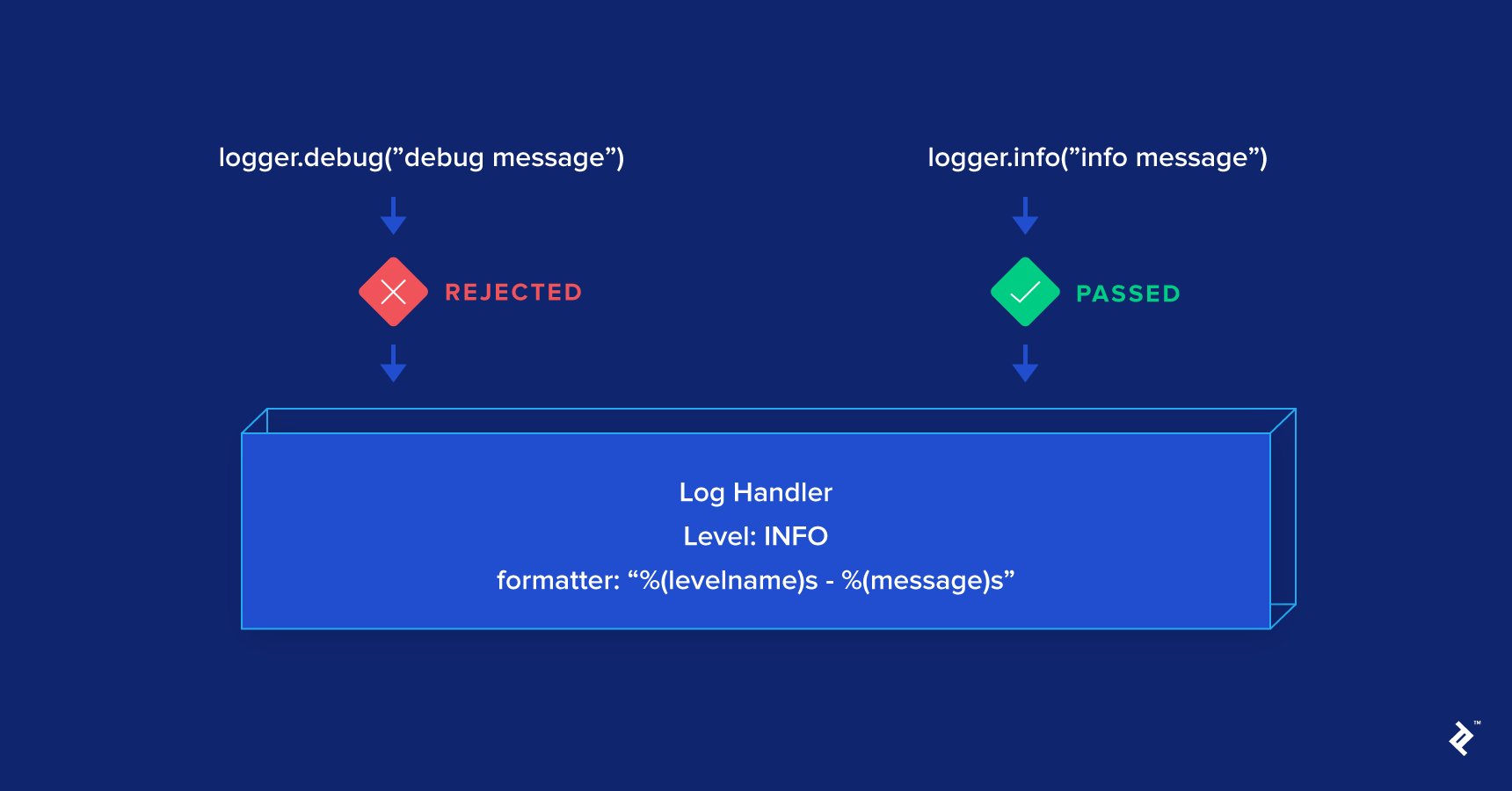

- A formatter that enriches the log with contextual data.

- A log level that filters logs based on their severity. For instance, a handler with the INFO level will disregard DEBUG logs.

Python’s standard library offers a variety of handlers sufficient for most common use cases: https://docs.python.org/3/library/logging.handlers.html#module-logging.handlers. StreamHandler and FileHandler are among the most frequently used:

| |

Understanding Python Loggers

Loggers are arguably the most frequently used component directly in code and also the most intricate. A new logger can be obtained through:

| |

Loggers have three primary attributes:

- Propagate: Determines if a log message should be passed to the logger’s parent. By default, this is set to True.

- Level: Like handler levels, logger levels filter logs by importance. However, unlike handlers, the level check occurs only at the “child” logger. Once a log propagates to its parents, the level is no longer checked, which can be counterintuitive.

- Handlers: A list of handlers to which the logger will dispatch log messages after they pass the level check. This enables flexible log handling. For example, you might have a file handler logging all DEBUG messages and an email handler dedicated to CRITICAL logs. The logger-handler relationship resembles a publisher-consumer model: A log is broadcast to all handlers once it clears the logger’s level check.

Loggers are uniquely identified by their names. Creating a logger named “example” means subsequent calls to logging.getLogger("example") will return the same logger instance:

| |

Loggers are organized hierarchically, with the root logger at the top, accessible via logging.root. This logger is invoked when using functions like logging.debug(). The root logger’s default level is WARN, discarding any logs with a lower level (like those from logging.info("info")). Additionally, the root logger’s default handler is only created when a log with a level higher than WARN is first logged. Directly using the root logger, or indirectly through methods like logging.debug(), is generally discouraged.

New loggers are, by default, children of the root logger:

| |

The “dot notation” allows creating hierarchical loggers. A logger named “parent.child” becomes a child of the “parent” logger if it exists. Otherwise, “parent.child” defaults to being a child of the root logger.

| |

To determine if a log message should pass based on its level, loggers utilize their “effective level.” This matches the actual logger level if it’s not NOTSET (ranging from DEBUG to CRITICAL). If the logger level is NOTSET, the effective level becomes the first ancestor’s level that isn’t NOTSET.

Since new loggers default to NOTSET and the root logger is at WARN, their effective level becomes WARN. Consequently, even with attached handlers, they’ll only process logs exceeding WARN:

| |

Essentially, the logger’s level determines whether a log is processed: Logs with a lower level than the logger’s level are ignored.

Recommended Practices for Python Logging

While incredibly useful, the logging module has quirks that can lead to frustration, even for experienced Python developers. Here are some best practices to follow:

- Configure the root logger but avoid directly using it in code—refrain from using functions like

logging.info(), which implicitly call the root logger. To capture errors from used libraries, configure the root logger to write to a file, facilitating easier debugging. By default, it only outputs tostderr, potentially losing logs. - When using logging, create a dedicated logger with

logging.getLogger(logger_name). While__name__is a common choice for the logger name, consistency is key. Consider using a function to return a logger with desired handlers for better organization (find an example on https://gist.github.com/nguyenkims/e92df0f8bd49973f0c94bddf36ed7fd0).

| |

Once a logger is created, you can use it like this:

| |

- Opt for RotatingFileHandler classes, such as TimedRotatingFileHandler, over FileHandler. These automatically rotate log files based on size or time intervals.

- Leverage tools like Sentry, Airbrake, or Raygun to automate error log capturing. These are invaluable in web applications where logs can become extensive and errors might go unnoticed. Such tools often provide detailed error context, including variable values, URLs, and affected users, aiding in debugging.

For a deeper dive into best practices, refer to “The 10 Most Common Mistakes That Python Developers Make” by Toptal developer Martin Chikilian.