Comprehending the Input/Output (I/O) model your application utilizes can significantly impact its performance, determining whether it thrives under pressure or crumbles when faced with real-world demands. While a small application with minimal traffic might not require intricate I/O handling, the scenario changes drastically as traffic surges. Opting for an unsuitable I/O model in such cases can lead to detrimental consequences.

Similar to situations with multiple viable approaches, the key lies in recognizing and understanding the inherent tradeoffs of each method. Let’s embark on a journey through the realm of I/O and explore the available options.

This article delves into a comparative analysis of backend language performance, examining Node, Java, Go, and PHP with Apache. We’ll dissect how these languages model I/O operations, analyze the pros and cons of each approach, and conclude with some basic performance benchmarks. If the I/O performance of your upcoming web application is a concern, this article is tailored for you.

I/O Fundamentals: A Concise Review

To grasp the intricacies of I/O, a revisit to the fundamental operating system level concepts is crucial. Although direct interaction with these concepts is rare, they are indirectly handled by your application’s runtime environment constantly, making their nuances significant.

System Calls

At the heart of I/O operations lie system calls, which can be summarized as follows:

- Your program, residing in the “user land,” needs to request the operating system kernel to execute an I/O operation on its behalf.

- This request is made through a “syscall,” a mechanism for your program to communicate its needs to the kernel. The implementation specifics might vary across operating systems, but the core concept remains consistent. A dedicated instruction transfers control from your program to the kernel, akin to a function call but with specialized handling for this context. Generally, syscalls are blocking, meaning your program patiently waits for the kernel’s response before proceeding.

- The kernel diligently performs the underlying I/O operation on the designated physical device, be it a disk, network card, or another, and subsequently responds to the syscall. In reality, fulfilling your request might involve multiple steps for the kernel, including waiting for device readiness and updating internal states. However, as an application developer, these intricate details are abstracted away, remaining the kernel’s responsibility.

Blocking vs. Non-blocking Calls

While syscalls are generally considered blocking, a subset exists known as “non-blocking” calls. These calls involve the kernel accepting your request, placing it in a queue or buffer, and immediately returning without waiting for the I/O operation’s completion. Essentially, they “block” for a minuscule duration, just enough to enqueue your request.

Illustrative examples (using Linux syscalls) can enhance clarity: - read() exemplifies a blocking call. By providing a file handle and a data buffer, the call patiently waits until the data is read from the file and populated into the buffer. This approach boasts simplicity. - On the other hand, epoll_create(), epoll_ctl(), and epoll_wait() represent non-blocking calls. They facilitate the creation of a group of handles to monitor, dynamically add or remove handles from this group, and then wait for any activity on these handles. This mechanism enables efficient management of numerous I/O operations using a single thread, but further explanation is provided later. While powerful, it introduces complexity compared to the blocking counterpart.

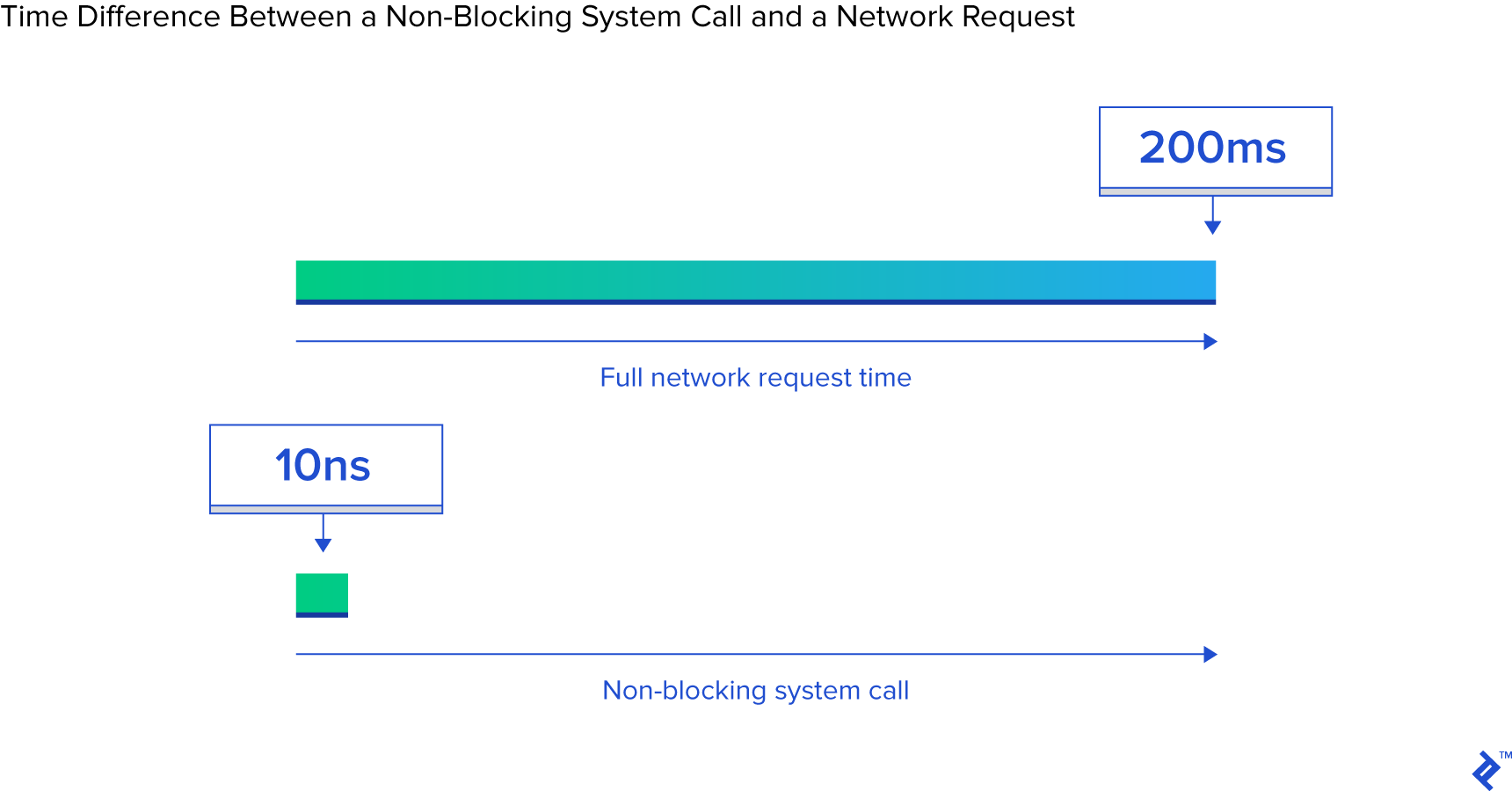

The magnitude of timing differences between these call types is crucial to comprehend. Assuming a 3GHz CPU core, ignoring potential optimizations, we have 3 billion cycles per second, translating to 3 cycles per nanosecond. A non-blocking system call might require around 10s of cycles, completing within “a handful of nanoseconds.” Conversely, a blocking call awaiting network data might take considerably longer, say 200 milliseconds (1/5 of a second). To put this into perspective, if the non-blocking call consumed 20 nanoseconds and the blocking call 200,000,000 nanoseconds, your process would endure a waiting period 10 million times longer for the blocking call.

The kernel equips us with tools for both blocking I/O (“fetch data from this network connection”) and non-blocking I/O (“notify me when data arrives on any of these connections”). The choice between these mechanisms directly influences the blocking duration experienced by the calling process, often with substantial differences.

Scheduling

When numerous threads or processes enter a blocking state, understanding the ensuing consequences is vital.

For our discussion, the distinction between a thread and a process is less critical. In practice, the most notable performance-related difference lies in their memory management: threads share the same memory space, while processes maintain separate memory spaces, leading to higher memory consumption by processes. However, when discussing scheduling, the focus shifts to a queue of entities (threads and processes) vying for execution time on the available CPU cores. With a scenario of 300 threads and 8 cores, execution time needs to be divided, allowing each entity its fair share. This distribution is achieved through a “context switch,” where the CPU swiftly alternates between running different threads or processes.

Context switches, however, come at a cost, consuming a certain amount of time. In optimized cases, this might be less than 100 nanoseconds, but depending on implementation details, processor architecture, CPU cache, and other factors, durations of 1000 nanoseconds or more are not uncommon.

The crux is, more threads (or processes) inevitably lead to more context switching. With thousands of threads and hundreds of nanoseconds per switch, the overall performance can degrade significantly.

In contrast, non-blocking calls essentially instruct the kernel: “Alert me only when new data or events are available on any of these connections.” This design efficiently handles substantial I/O loads while minimizing context switching.

Have we retained our focus so far? Now comes the intriguing part: Let’s analyze how popular languages leverage these tools and discern the tradeoffs they make between user-friendliness, performance, and other noteworthy aspects.

It’s important to remember that while the examples presented here are simplified (and truncated for brevity), any operation involving I/O, whether it be database access, interaction with external caching systems (memcache, etc.), or anything similar, ultimately boils down to some form of I/O call with analogous implications. Additionally, in scenarios where I/O is categorized as “blocking” (PHP, Java), the HTTP request and response handling themselves involve blocking calls. This highlights the presence of more I/O hidden within the system, carrying its own set of performance considerations.

The selection of a programming language for a project hinges on numerous factors, and performance is just one piece of the puzzle. However, if your program’s performance is anticipated to be primarily constrained by I/O, where I/O efficiency is paramount, these are the nuances you need to be aware of.

The “Simplicity First” Approach: PHP

Back in the 1990s, amidst the prevalence of Converse shoes, many were crafting CGI scripts using Perl. Then PHP emerged, and despite receiving its fair share of criticism, it significantly streamlined the creation of dynamic web pages.

PHP’s model is inherently straightforward. While variations exist, a typical PHP server operates as follows:

An HTTP request originates from a user’s browser, reaching your Apache web server. Apache diligently spawns a separate process for each incoming request, employing optimizations to reuse processes whenever possible to minimize overhead (process creation is relatively resource-intensive). Subsequently, Apache invokes PHP, instructing it to execute the corresponding .php file located on disk. The PHP code springs to life, diligently executing blocking I/O calls. A call to file_get_contents() in PHP, for instance, triggers underlying read() syscalls, patiently waiting for the results.

Notably, the code itself is directly embedded within your web page, and operations maintain their blocking nature:

| |

Visualizing the interaction with the system:

Simplicity reigns supreme: one process dedicated to each request. I/O calls faithfully block until completion. The advantage? It’s elegantly simple and undeniably effective. However, the downside surfaces when confronted with 20,000 concurrent clients—your server is likely to buckle under the pressure. This approach lacks scalability because the kernel’s provisions for high-volume I/O handling (epoll, etc.) remain untapped. Adding insult to injury, dedicating a separate process to each request can strain system resources, particularly memory, which often becomes the first bottleneck in such situations.

Note: Ruby’s approach closely mirrors PHP’s, and for our high-level comparison, they can be considered broadly equivalent.

The Multithreaded Path: Java

Enter Java, arriving around the time owning a domain name became trendy, prompting the ubiquitous addition of “.com” to sentences. Java brought forth multithreading as a language feature, a remarkable capability, especially for its time.

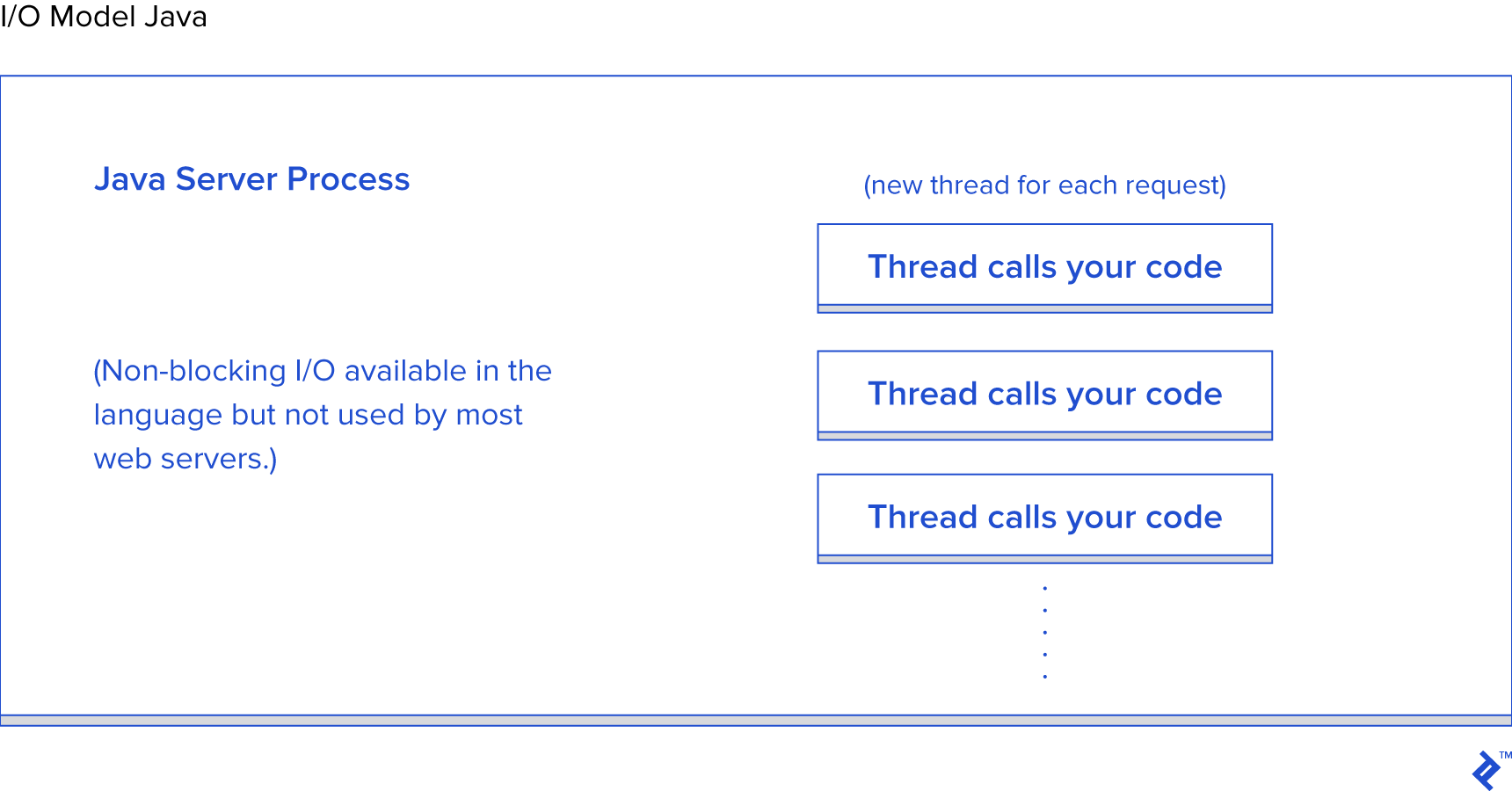

Most Java web servers operate by spawning a new thread of execution for each incoming request, ultimately culminating in the invocation of your function, the one you painstakingly crafted as the application developer.

Performing I/O within a Java Servlet typically resembles:

| |

With our doGet method representing a single request and executing within its own dedicated thread, instead of separate processes demanding their own memory space, we achieve thread-level isolation. This grants advantages such as shared state and cached data among threads, facilitated by their access to each other’s memory. However, the impact on scheduling remains nearly identical to the PHP example. Each request is assigned a new thread, and various I/O operations patiently block within that thread until the request is fully served. Thread pools mitigate the cost of repeated creation and destruction, but nonetheless, thousands of connections translate to thousands of threads, ultimately burdening the scheduler.

A significant milestone was reached with Java version 1.4 (further enhanced in 1.7), introducing support for non-blocking I/O calls. While adoption in most applications, both web-based and otherwise, remains limited, the capability exists. Certain Java web servers attempt to leverage this feature in various ways; however, the vast majority of deployed Java applications still adhere to the aforementioned model.

Java brings us closer to an ideal solution, offering valuable out-of-the-box I/O functionality. However, the fundamental challenge of handling a heavily I/O-bound application inundated with thousands of blocking threads persists.

Non-blocking I/O as a Core Tenet: Node

In the realm of enhanced I/O, Node.js has emerged as the popular choice. Even those with a cursory understanding of Node have encountered claims of its “non-blocking” nature and efficient I/O handling. While generally true, the intricacies lie in the implementation details, which significantly influence performance.

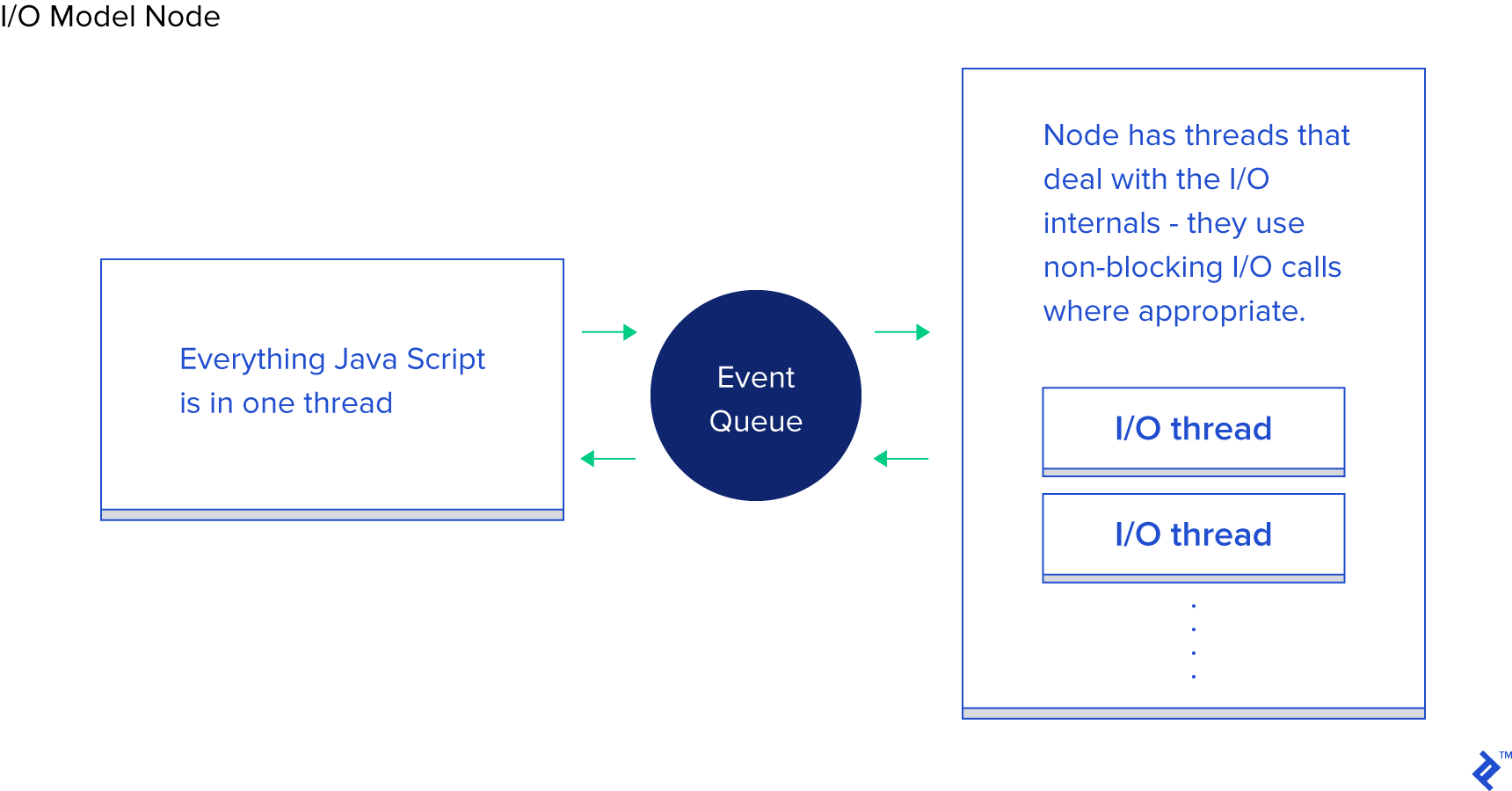

Node’s paradigm shift lies in its approach to request handling. Instead of dictating “write your code here to process the request,” it advocates for “write code here to initiate request handling.” Each I/O-bound operation is initiated with a provided callback function, which Node diligently invokes upon completion.

A typical Node code snippet for performing an I/O operation during a request resembles:

| |

As evident, two callback functions grace this example. The first springs to life when a request is initiated, while the second is summoned when the requested file data becomes available.

This structure empowers Node to efficiently manage I/O operations between these callbacks. The relevance is further amplified in scenarios involving database calls within Node, although the principle remains identical. You initiate the database call, equip Node with a callback function, and it elegantly performs the I/O operations separately using non-blocking calls, ultimately invoking your callback when the requested data is ready. This mechanism of queuing I/O calls, relinquishing control to Node, and receiving a notification upon completion is aptly termed the “Event Loop.” And it performs admirably.

However, this model comes with a caveat. Under the hood, its foundation lies more in the implementation of the V8 JavaScript engine (powering both Chrome and Node) 1 than anything else. Your meticulously crafted JS code executes within a single thread. Ponder that for a moment. While I/O benefits from efficient non-blocking techniques, your CPU-bound JS operations are confined to a single thread, with each chunk of code blocking the next. A common illustration is iterating over database records for processing before relaying the results to the client. Here’s a snippet demonstrating this behavior:

| |

Despite Node’s efficient I/O handling, the for loop in this example consumes precious CPU cycles within your solitary main thread. Consequently, with 10,000 active connections, this seemingly innocuous loop has the potential to bring your entire application to a grinding halt, depending on its duration. Each request patiently awaits its turn, sharing a sliver of time within the main thread.

This entire concept hinges on the premise that I/O operations are the bottleneck, prioritizing their efficient handling even at the expense of serial processing. While true in certain scenarios, it doesn’t hold universally.

Furthermore, and this borders on personal opinion, the abundance of nested callbacks can hinder code readability and maintainability. It’s not uncommon to encounter callbacks nested four, five, or even more levels deep within Node code.

Once again, we encounter tradeoffs. Node’s model excels when I/O poses the primary performance hurdle. However, its Achilles’ heel lies in the potential for CPU-intensive code within a request handler to cripple performance for all connections if left unchecked.

Intrinsically Non-blocking: Go

Before delving into Go’s approach, transparency dictates that I confess my admiration for Go. Having employed it in numerous projects, I’m an advocate for its productivity advantages, which I’ve witnessed firsthand.

Now, let’s examine how Go tackles I/O. A key distinguishing feature of Go is its built-in scheduler. Unlike the one-to-one mapping between threads of execution and OS threads found elsewhere, Go introduces the concept of “goroutines.” The Go runtime intelligently manages goroutines, assigning them to OS threads for execution or suspending them based on their current activity. Each incoming request to Go’s HTTP server is gracefully handled within its own dedicated goroutine.

A visual representation of the scheduler’s inner workings:

Behind the scenes, this is achieved through various points within the Go runtime. When an I/O call is made (write, read, connect, etc.), the runtime cleverly suspends the current goroutine, preserving the necessary information to awaken it when further action is possible.

Essentially, the Go runtime performs a task conceptually similar to Node’s approach, but with a crucial difference: the callback mechanism is seamlessly integrated into the I/O call implementation, intricately intertwined with the scheduler. Moreover, it doesn’t suffer from the limitation of confining all handler code to a single thread. Go’s scheduler deftly distributes your goroutines across an appropriate number of OS threads based on its internal logic. The result is elegant code like this:

| |

The code structure closely resembles the simplicity of earlier approaches while achieving non-blocking I/O under the hood.

In many situations, this achieves the coveted “best of both worlds.” Non-blocking I/O gracefully handles performance-critical sections, while your code retains a blocking structure, enhancing readability and maintainability. The harmonious interplay between the Go scheduler and the OS scheduler takes care of the rest. While not pure magic, understanding the intricacies of this interaction proves beneficial when building large systems. However, the “out-of-the-box” experience is smooth and scales remarkably well.

Go might have its shortcomings, but its I/O handling generally isn’t one of them.

Benchmarks: Unveiling Performance

Providing precise timings for the context switching involved in these various models proves challenging. Moreover, its practical usefulness to you is debatable. Therefore, instead of raw numbers, I present some fundamental benchmarks comparing the overall HTTP server performance of these environments. Bear in mind that numerous factors influence end-to-end HTTP request/response performance, and these numbers serve as a general comparison based on my testing.

For each environment, I crafted code to read a 64KB file containing random bytes, perform a SHA-256 hash on it N times (N controlled via a query parameter, e.g., .../test.php?n=100), and finally output the resulting hexadecimal hash. This choice stems from its simplicity, providing a consistent I/O workload and a controlled way to introduce CPU load.

Refer to these benchmark notes for details on the environments used.

Let’s start with low concurrency. Running 2000 iterations with 300 concurrent requests and a single hash per request (N=1) yields:

Drawing definitive conclusions from a single graph is ill-advised, but these results suggest that at this connection volume and computation level, the observed times are more representative of the general execution characteristics of the languages themselves, rather than being dominated by I/O. Notably, languages often categorized as “scripting languages” (dynamic typing, interpreted execution) exhibit slower performance.

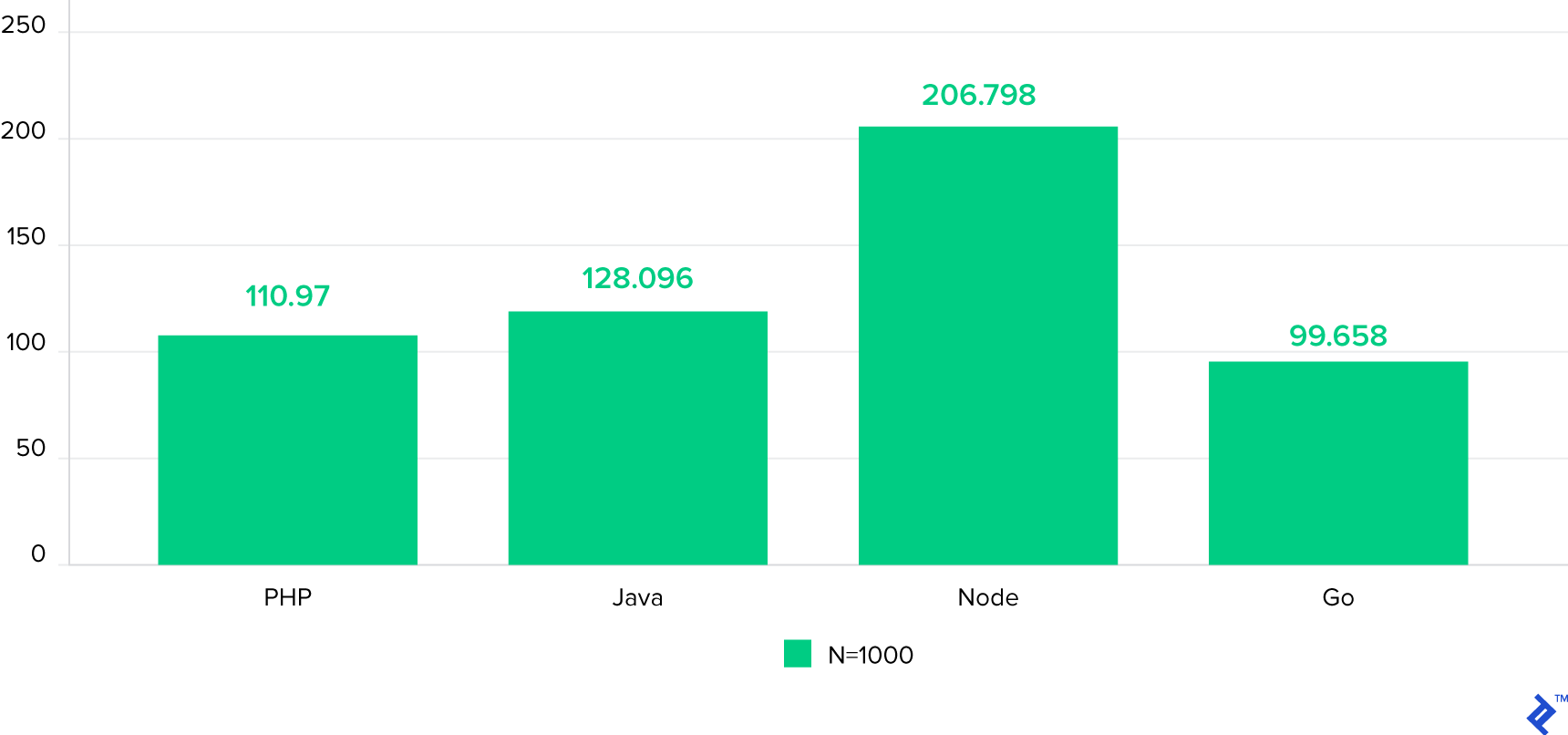

Now, let’s crank up the CPU load by increasing N to 1000, maintaining 300 concurrent requests—same load, but 100 times more hash iterations:

Node’s performance takes a noticeable hit as CPU-intensive operations within each request begin to contend. Interestingly, PHP’s performance relative to the others improves significantly, surpassing Java in this test. (Noteworthy: PHP’s SHA-256 implementation is written in C, and with 1000 hash iterations, the execution spends a significant portion of time within that loop).

Next, let’s push the boundaries with 5000 concurrent connections (N=1) or as close to that as achievable. Regrettably, most environments exhibited a non-negligible failure rate. This chart focuses on the total requests per second, with higher values indicating better performance:

The picture changes drastically. While speculative, it appears that under high connection volume, the per-connection overhead associated with spawning new processes and the accompanying memory footprint in PHP+Apache becomes the dominant factor, hindering PHP’s performance. Go emerges as the clear victor, followed by Java, Node, and lastly PHP.

While numerous factors contribute to overall throughput, varying significantly between applications, a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms and tradeoffs involved proves invaluable.

In Conclusion

The evolution of programming languages has gone hand in hand with the development of solutions for building large-scale, I/O-intensive applications.

To be fair, both PHP and Java, despite the descriptions provided here, offer implementations of non-blocking I/O available for use in web applications. However, these approaches are less prevalent, and the operational overhead associated with maintaining servers using them shouldn’t be overlooked. Additionally, your codebase typically requires restructuring to function correctly in such environments. “Normal” PHP or Java web applications usually demand significant modifications to operate seamlessly.

Comparing a few key factors influencing both performance and ease of use:

| Language | Threads vs. Processes | Non-blocking I/O | Ease of Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHP | Processes | No | |

| Java | Threads | Available | Requires Callbacks |

| Node.js | Threads | Yes | Requires Callbacks |

| Go | Threads (Goroutines) | Yes | No Callbacks Needed |

Threads generally exhibit superior memory efficiency compared to processes due to their shared memory space. Coupled with the advantages of non-blocking I/O, it becomes evident that moving down the list generally leads to improved I/O setups, at least considering the factors discussed here. Therefore, if I were to declare a winner in this comparison, Go would undoubtedly claim the crown.

However, in practice, the choice of an environment for building your application is deeply intertwined with your team’s familiarity with it and the overall productivity achievable. Blindly jumping into Node or Go development might not be suitable for every team. In fact, the availability of skilled developers or the existing expertise within your team is often cited as the primary deterrent to adopting a different language or environment. That being said, the landscape has shifted dramatically over the past fifteen years.

Hopefully, this exploration has shed light on the inner workings of I/O handling, providing you with insights and ideas for tackling real-world scalability challenges in your applications. Happy coding!