It’s undeniable that Kotlin has overtaken Java as the go-to language for Android, becoming Google’s favorite and thus the more suitable option for new mobile apps. However, both languages boast a wide array of advantages for general-purpose programming. Consequently, understanding their differences is crucial for developers, especially for tasks like transitioning from Java to Kotlin. This article will delve into the disparities and commonalities between Kotlin and Java, providing insights for informed decision-making and seamless switching between the two.

Are Kotlin and Java Alike?

From a broader perspective, Kotlin and Java share a considerable amount of common ground. Both operate on the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) rather than directly compiling to native code, and they can interact with each other effortlessly: Java code can be called from Kotlin and vice versa. Java proves useful in various domains, including server-side applications, databases, web front-end applications, embedded systems, enterprise applications, mobile development, and beyond. Similarly, Kotlin exhibits versatility, targeting the JVM, Android, JavaScript, and Kotlin/Native, while also being applicable to server-side, web, and desktop development.

Java, initially released in 1996, holds a significant maturity advantage over Kotlin. Although Kotlin 1.0 emerged much later in 2016, it quickly rose to prominence, becoming the officially preferred language for Android development in 2019. However, outside the Android realm, there is no recommendation to replace Java with Kotlin.

Year | Java | Kotlin |

|---|---|---|

1995–2006 | JDK Beta, JDK 1.0, JDK 1.1, J2SE 1.2, J2SE 1.3, J2SE 1.4, J2SE 5.0, Java SE 6 | N/A |

2007 | Project Loom first commit | N/A |

2010 | N/A | Kotlin development started |

2011 | Java SE 7 | Kotlin project announced |

2012 | N/A | Kotlin open sourced |

2014 | Java SE 8 (LTS) | N/A |

2016 | N/A | Kotlin 1.0 |

2017 | Java SE 9 | Kotlin 1.2; Kotlin support for Android announced |

2018 | Java SE 10, Java SE 11 (LTS) | Kotlin 1.3 (coroutines) |

2019 | Java SE 12, Java SE 13 | Kotlin 1.4 (interoperability for Objective-C and Swift); Kotlin announced as Google’s preferred language for developers |

2020 | Java SE 14, Java SE 15 | N/A |

2021 | Java SE 16, Java SE 17 (LTS) | Kotlin 1.5, Kotlin 1.6 |

2022 | Java SE 18, JDK 19 | Kotlin 1.7 (alpha version of Kotlin K2 compiler), Kotlin 1.8 |

2023 | Java SE 20, Java SE 21, JDK 20, JDK 21 | Kotlin 1.9 |

2024 | Java SE 22 (scheduled) | Kotlin 2.0 (potentially) |

Kotlin vs. Java: Evaluating Performance and Memory Usage

Prior to delving into the specifics of Kotlin and Java’s features, let’s assess their performance and memory consumption, as these aspects often hold considerable weight for developers and clients alike.

Kotlin, Java, and other JVM languages, while not identical, exhibit relatively similar performance characteristics, particularly when juxtaposed with languages belonging to different compiler families like GCC or Clang. The JVM’s initial design in the 1990s targeted embedded systems with limited resources. This resulted in two primary limitations:

- Streamlined JVM Bytecode: The latest JVM iteration, upon which both Kotlin and Java are compiled, comprises a mere 205 instructions. In stark contrast, a modern x64 processor can effortlessly accommodate over 6,000 encoded instructions, with the precise count depending on the calculation method employed.

- Runtime (vs. Compile-Time) Operations: The emphasis on a multiplatform approach (“Write once and run anywhere”) prioritizes optimizations performed at runtime instead of compile time. Consequently, the JVM translates the majority of its bytecode into instructions during program execution. Nevertheless, to enhance performance, developers can leverage open-source JVM implementations such as HotSpot, which pre-compiles the bytecode to expedite its execution by the interpreter.

Given their comparable compilation processes and runtime environments, the performance disparities between Kotlin and Java are generally minor and stem from their unique features. For instance:

- Kotlin’s inline functions, which circumvent the overhead of function calls, contribute to improved performance, while Java’s conventional function calls introduce additional memory overhead.

- Kotlin’s higher-order functions outperform Java lambdas by avoiding the dedicated

InvokeDynamiccall, resulting in enhanced performance. - Kotlin’s generated bytecode incorporates assertions for nullity checks when interacting with external dependencies, leading to a slight performance disadvantage compared to Java.

Shifting our focus to memory usage, it’s theoretically true that utilizing objects to represent primitive data types (as Kotlin does) necessitates more memory allocation compared to using primitive data types directly (as in Java). However, in practical scenarios, Java’s bytecode often relies on autoboxing and unboxing calls to manipulate objects, which can introduce computational overhead if excessively employed. For example, Java’s String.format method exclusively accepts objects as input, necessitating the boxing of a Java int into an Integer object before invoking String.format.

Overall, the performance and memory characteristics of Java and Kotlin are largely comparable. While online benchmarks may reveal minor discrepancies in micro-benchmarks, these findings cannot be extrapolated to gauge the behavior of full-fledged production applications.

Contrasting Unique Features

Despite their fundamental similarities, Kotlin and Java possess distinct, unique features. Since Kotlin’s ascension as Google’s preferred language for Android development, I’ve found extension functions and explicit nullability to be the most beneficial additions. Conversely, when working with Kotlin, the Java features I find myself missing the most are the protected keyword and the ternary operator.

Let’s delve into a more granular comparison of the features offered by Kotlin and Java. For a more interactive learning experience, feel free to experiment with the provided examples using the Kotlin Playground or a Java compiler.

Feature | Kotlin | Java | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

Extension functions | Yes | No | Allows you to extend a class or an interface with new functionalities such as added properties or methods without having to create a new class: |

Smart casts | Yes | No | Keeps track of conditions inside if statements, safe casting automatically:Kotlin also provides safe and unsafe cast operators: |

Inline functions | Yes | No | Reduces overhead memory costs and improves speed by inlining function code (copying it to the call site): inline fun example(). |

Native support for delegation | Yes | No | Supports the delegation design pattern natively with the use of the by keyword: class Derived(b: Base) : Base by b. |

Type aliases | Yes | No | Provides shortened or custom names for existing types, including functions and inner or nested classes: typealias ShortName = LongNameExistingType. |

Non-private fields | No | Yes | Offers protected and default (also known as package-private) modifiers, in addition to public and private modifiers. Java has all four access modifiers, while Kotlin is missing protected and the default modifier. |

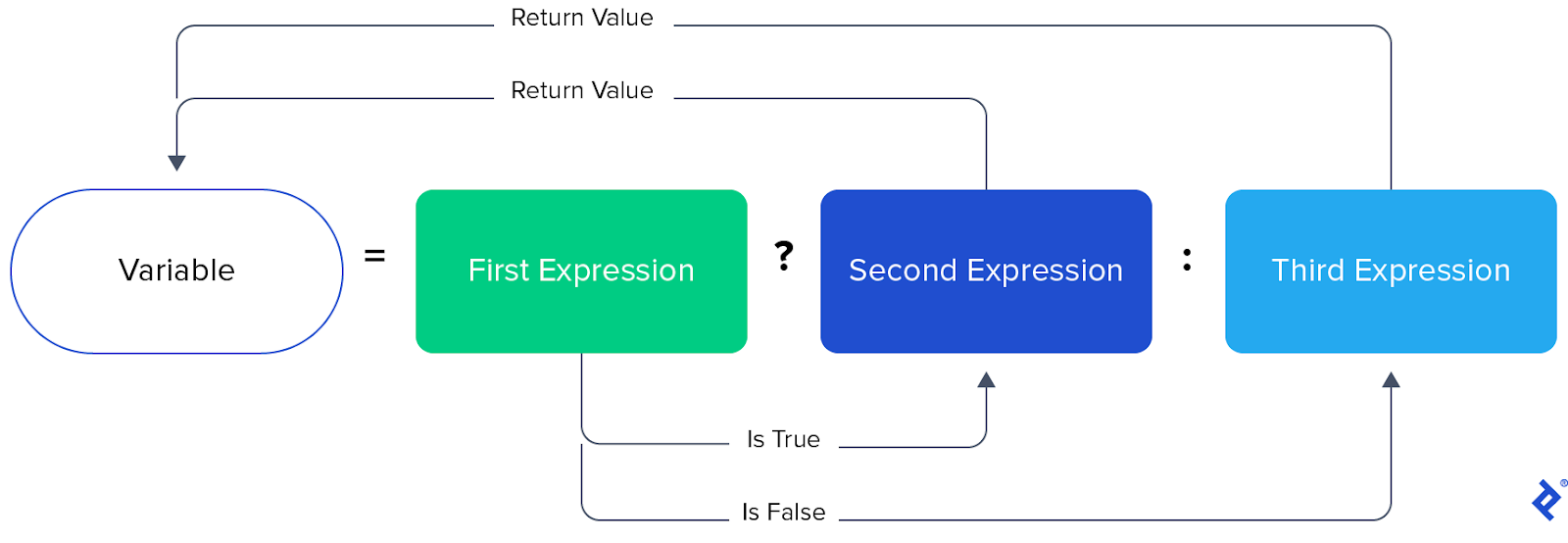

Ternary operator | No | Yes | Replaces an if/else statement with simpler and more readable code: |

Implicit widening conversions | No | Yes | Allows for automatic conversion from a smaller data type to a larger data type: |

Checked exceptions | No | Yes | Requires, at compile time, a method to catch exceptions with the throws keyword or handles exceptions with a try-catch block.Note: Checked exceptions were intended to encourage developers to design robust software. However, they can create boilerplate code, make refactoring difficult, and lead to poor error handling when misused. Whether this feature is a pro or con depends on developer preference. |

One topic intentionally omitted from this table is null safety in Kotlin versus Java, as it merits a more in-depth analysis.

Kotlin vs. Java: A Closer Look at Null Safety

In my view, non-nullability stands out as one of Kotlin’s most significant advantages. This feature saves developers valuable time by eliminating the need to handle NullPointerExceptions (which are classified as RuntimeExceptions).

In Java, any variable can be assigned a null value by default:

| |

Kotlin, on the other hand, offers two distinct options: declaring a variable as either nullable or non-nullable:

| |

As a best practice, I generally default to non-nullable variables and minimize the use of nullable ones. The examples provided here are solely for demonstrating the differences between Kotlin and Java. Novice Kotlin developers should be wary of unnecessarily declaring variables as nullable (which can occur when converting Java code to Kotlin).

However, there are certain scenarios where using nullable variables in Kotlin is justified:

Scenario | Example |

|---|---|

You are searching for an item in a list that is not there (usually when dealing with the data layer). | |

You want to initialize a variable during runtime, using lateinit. | |

When I initially started using Kotlin, I admit to overusing lateinit variables. However, I’ve since drastically reduced their usage, primarily reserving them for defining view bindings and variable injections in Android development:

| |

In summary, Kotlin’s approach to null safety offers increased flexibility and a superior developer experience compared to Java.

Shared Feature Discrepancies: Navigating Between Java and Kotlin

Although each language boasts unique features, Kotlin and Java share a substantial number of features as well. Understanding their subtle differences is crucial for smooth transitions between the two languages. Let’s explore four common concepts that function differently in Kotlin and Java:

Feature | Java | Kotlin |

|---|---|---|

Data transfer objects (DTOs) | Java records, which hold information about data or state and include toString, equals, and hashCode methods by default, have been available since Java SE 15: | Kotlin data classes function similarly to Java records, with toString, equals, and copy methods available: |

Lambda expressions | Java lambda expressions (available since Java 8) follow a simple parameter -> expression syntax, with parentheses used for multiple parameters: (parameter1, parameter2) -> { code }: | Kotlin lambda expressions follow the syntax { parameter1, parameter2 -> code } and are always surrounded by curly braces: |

Java threads make concurrency possible, and the java.util.concurrency package allows for easy multithreading through its utility classes. The Executor and ExecutorService classes are especially beneficial for concurrency. (Project Loom also offers lightweight threads.) | Kotlin coroutines, from the kotlinx.coroutines library, facilitate concurrency and include a separate library branch for multithreading. The memory manager in Kotlin 1.7.20 and later versions reduces previous limitations on concurrency and multithreading for developers moving between iOS and Android. | |

Static behavior in classes | Java static members facilitate the sharing of code among class instances and ensure that only a single copy of an item is created. The static keyword can be applied to variables, functions, blocks, and more: | Kotlin companion objects offer static behavior in classes, but the syntax is not as straightforward: |

Naturally, Kotlin and Java also differ in their syntax. While a comprehensive discussion of every syntax difference is beyond the scope of this article, examining loops should provide a glimpse into the overall situation:

Loop Type | Java | Kotlin |

|---|---|---|

for, using in | | |

for, using until | | |

forEach | | |

while | | |

A thorough understanding of Kotlin’s features will greatly facilitate transitions between Kotlin and Java.

Android Project Planning: Factors Beyond Language Choice

We’ve covered numerous crucial factors to consider when choosing between Kotlin and Java in a general-purpose context. However, no Kotlin versus Java analysis would be complete without addressing the elephant in the room: Android.

If you’re starting an Android project from scratch and pondering whether to use Java or Kotlin, the answer is clear: choose Kotlin, Google’s preferred language for Android development.

However, this question becomes less relevant for existing Android applications. Based on my experience working with a diverse clientele, the more pressing questions are: How are you addressing technical debt? and How are you prioritizing developer experience (DX)?

So, how are you tackling technical debt? If your Android app is still using Java in 2023, your company is likely focused on pushing out new features rather than confronting technical debt. This is understandable, given the competitive market and the demand for rapid app update cycles. However, technical debt has insidious consequences: it increases costs with each update as engineers are forced to work around unstable and difficult-to-refactor code. Companies can easily find themselves trapped in a vicious cycle of mounting technical debt and escalating costs. It may be worthwhile to pause and invest in long-term solutions, even if it entails large-scale code refactoring or migrating your codebase to a modern language like Kotlin.

And how are you supporting your developers through DX? Developers need support throughout their careers:

- Junior developers thrive with access to appropriate resources.

- Mid-level developers grow through opportunities to lead and mentor.

- Senior developers require the autonomy to design and implement elegant code.

Prioritizing DX for senior developers is particularly crucial, as their expertise has a cascading effect on the entire engineering team. Senior developers are intrinsically motivated to learn and experiment with the latest technologies. Staying abreast of emerging trends and language releases enables your team members to reach their full potential. While this holds true regardless of the chosen language, different languages evolve at different paces: with rapidly evolving languages like Kotlin, an engineer working on legacy code can fall behind in less than a year; with mature languages like Java, this process takes longer.

Kotlin and Java: Two Powerful Tools in the Developer’s Arsenal

While Java boasts a wide range of applications, Kotlin has undoubtedly usurped its position as the preferred language for developing new Android apps. Google has thrown its full weight behind Kotlin, prioritizing it in their latest technologies. Developers working on existing apps should consider incorporating Kotlin into any new code—IntelliJ provides an automatic Java to Kotlin tool—and should carefully weigh factors beyond the initial question of language choice.

The editorial team of the Toptal Engineering Blog expresses its sincere gratitude to Thomas Wuillemin for reviewing the code samples and other technical content presented in this article.