This guide explores frequent errors made by Django developers and how to circumvent them. It’s relevant even for seasoned developers since issues like bloated settings or naming clashes in static assets can affect anyone.

Django, a free, open-source Python web framework, simplifies common development hurdles and enables building versatile, well-structured applications. Its rich feature set includes the Admin interface, ORM, Routing, and Templating, making it my top pick. These features expedite development, letting me focus on core tasks rather than repetitive basics.

Django’s standout feature is its highly configurable admin interface, generated dynamically from your model schemas and admin panel models. It empowers users to manage aspects like ACLs, row-level permissions, filters, ordering, widgets, forms, extra URL helpers, and more. Every application eventually needs an admin panel, and Django makes creating one quick and flexible.

Django’s powerful ORM seamlessly integrates with major databases. Its lazy loading only queries the database when needed, unlike some ORMs. Supporting major SQL commands and functions from Python code makes it efficient and comfortable to use.

Django’s flexible and robust templating engine supports standard filters and tags and allows creating custom filters and tags. It even supports third-party template engines with an API for seamless integration through standard shortcut functions.

Besides these, Django offers other major features like a URL router for parsing incoming requests and building URLs from schemas. The framework as a whole provides a smooth development experience. Whenever you need help, just consult the documentation.

Misstep 1: Utilizing the Global System Python Environment for Project Dependencies

Avoid using Python’s global environment for project dependencies to prevent conflicts. Python struggles with multiple package versions simultaneously, posing problems when different projects demand incompatible versions of the same package.

This often trips up newcomers unfamiliar with Python’s environment isolation. Let’s delve into common isolation methods:

- virtualenv: This Python package creates a dedicated environment folder with scripts for activation, deactivation, and package management within the environment. Its simplicity makes it my preferred choice. I typically create the environment adjacent to the project folder.

- virtualenvwrapper: This globally installed Python package offers tools for managing virtual environments: creation, deletion, activation, etc. While it stores all environments in a central (configurable) location, I find no significant advantage over

virtualenv. - Virtual Machines (VM): For ultimate isolation, dedicate an entire VM to your application. Numerous tools are available, including the free VirtualBox, along with VMware, Parallels, and Proxmox (my favorite, with a free version). When combined with VM automation like Vagrant, this becomes incredibly powerful.

- Containers: In recent years, I’ve embraced Docker for almost every new project. Docker’s rich feature set and third-party automation tools, coupled with layer caching for rapid rebuilds, make it fantastic. Within containers, I use the global system Python environment since each container has its isolated filesystem, separating projects at a high level. Docker accelerates onboarding for new team members, especially those familiar with it.

Personally, I lean towards the virtualenv package and Docker for isolating and managing project dependencies.

Misstep 2: Neglecting to Freeze Project Dependencies in a requirements.txt File

Initiate every Python project with a requirements.txt file and a fresh, isolated environment. While you install packages via pip/easy_install, diligently record them in your requirements.txt. This streamlines project deployment on servers and allows teammates to easily set up the project.

Crucially, pin specific dependency versions in your requirements.txt. Different versions often bring varying modules, functions, and even function parameters. Even minor changes can break your application. Without version pinning, your build system will always grab the latest package version, potentially causing havoc in live projects with scheduled deployments.

Always pin your production packages! My personal preference is pip-tools, a handy tool for managing dependencies. It generates a requirements.txt file that meticulously pins your entire dependency tree, including dependencies of dependencies.

Suppose you want to update specific dependencies (e.g., only Django/Flask/any framework). With “pip freeze,” identifying which dependency belongs to which package becomes challenging, making targeted upgrades difficult. Pip-tools solves this by automatically pinning packages based on your pinned dependency, effortlessly resolving updates. As a bonus, its comment system clearly marks the origin of each package within the requirements.txt.

For added safety, back up your dependency source files. Whether it’s your local filesystem, a Git repository, S3, FTP, or SFTP, having a copy readily available is crucial. There have been instances where a relatively minor package being unlisted broke a large number of packages on npm. Conveniently, pip allows downloading dependency source files—explore pip help download for details.

Misstep 3: Sticking to Old-Style Python Functions Over Class-Based Views

While small Python functions in views.py can be useful for tests or utilities, favor Class-Based Views (CBVs) in your applications.

CBVs are generic views offering abstract classes that implement common web development tasks. Built by experts, they encapsulate standard behaviors and offer a well-structured API. Leveraging CBVs brings the benefits of object-oriented programming, resulting in cleaner, more readable code. They eliminate the headache of using Django’s standard view functions for tasks like listings, CRUD operations, and form processing. Simply extend the appropriate CBV and override properties or functions to tailor the view’s behavior.

Consider using mix-ins to streamline your project. These can override default CBV behaviors for building view contexts, handling row-level authorization, automatically generating template paths based on your application structure, integrating smart caching, and more.

I developed Django Template Names to standardize template naming based on application and view class names, saving me time and effort. Include the mix-in in your CBV—class Detail(TemplateNames, DetailView):—and it’s good to go! You can even override its functions to add mobile-responsive templates, user-agent-specific templates, or any custom logic.

Misstep 4: Creating Fat Views and Skinny Models

Putting application logic in views instead of models leads to bloated views and anemic models. Strive for fat models and skinny views.

Deconstruct your logic into concise model methods. This promotes reusability from multiple sources—admin interface, frontend UI, API endpoints, various views—with just a few lines of code, avoiding repetitive code. For instance, instead of embedding email-sending logic in every controller, extend your model with an email function.

This approach also simplifies unit testing. You can test the email logic in one central location rather than repeatedly across every controller that uses it.

Explore the Django Best Practices project for a deeper dive into this issue. The solution is straightforward: Fat models, skinny views. Implement this in your next project or refactor your current one.

Misstep 5: Maintaining a Monolithic, Unwieldy Settings File

Even a fresh Django project settings file project comes with a sizable settings file. In real-world scenarios, this file can balloon to 700+ lines, becoming a maintenance nightmare, especially with custom configurations for development, production, and staging environments.

While manual splitting and custom loaders are options, consider Django Split Settings, a robust Python package I co-authored.

This package provides two functions: optional and include. These support wildcard paths and import configuration files within the same context, enabling you to construct your configuration by referencing entries from previously loaded files. With negligible impact on Django’s performance, it’s suitable for any project.

Here’s a minimal configuration example:

| |

Misstep 6: Building an All-Encompassing Application, Poor Structure, and Misplaced Resources

Django projects typically comprise multiple applications. In Django’s terminology, an application is a Python package with at least __init__.py and models.py files (though in recent versions, models.py is optional).

These applications can house Python modules, Django-specific modules (views, URLs, models, admin, forms, template tags, etc.), static files, templates, database migrations, management commands, unit tests, and more. Break down monolithic applications into smaller, reusable applications units with clear purposes, each describable in a sentence or two. For instance: “Handles user registration and email activation.”

A good practice is to designate the project folder as project and organize applications within project/apps/. Further, store all application dependencies in their subfolders.

Examples:

- Static files:

project/apps/appname/static/appname/ - Template tags:

project/apps/appname/templatetags/appname.py - Template files:

project/apps/appname/templates/appname/

Always prefix subfolders with the application name. This is crucial because all static folders merge into one, and naming conflicts (e.g., js/core.js) can lead to the last application in settings.INSTALLED_APPLICATIONS overriding others. I once spent hours debugging this issue, only to discover that another developer’s work on a custom SPA admin panel had caused a file override due to identical naming.

Here’s an example structure for a portal application rich in resources and modules:

| |

Such a structure makes it easy to extract an application into a reusable Python package. You can even publish it on PyPi as open source or move it elsewhere effortlessly.

Your final project structure might resemble this:

| |

Real-world projects are naturally more intricate, but this structure brings a sense of order and simplicity.

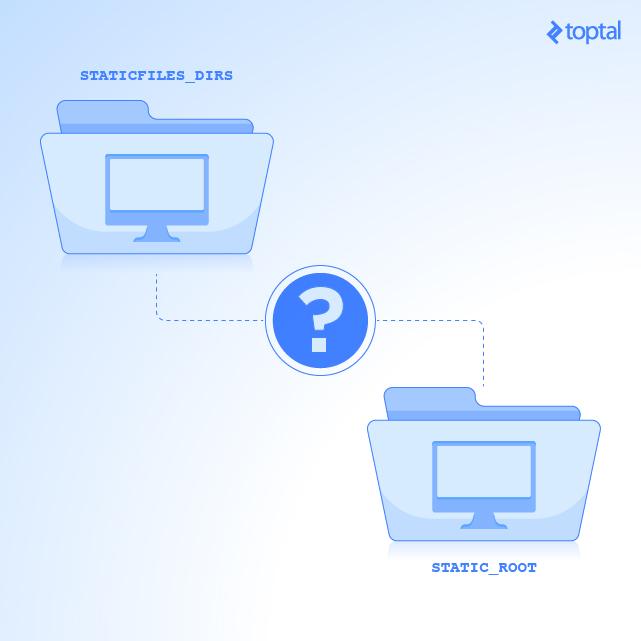

Misstep 7: Misunderstanding STATICFILES_DIRS and STATIC_ROOT - A Common Pitfall

Static files are unchanging assets like JavaScript, CSS, images, and fonts. Django “collects” them into a public directory during deployment.

In development (python manage.py runserver), Django locates static files using the STATICFILES_FINDERS setting. It first searches directories listed in STATICFILES_DIRS. If unsuccessful, it utilizes django.contrib.staticfiles.finders.AppDirectoriesFinder to scan the static folder of each installed application, enabling reusable applications bundled with their static assets.

In production, a separate web server like Nginx serves static files. This server is oblivious to your Django project’s structure or static file locations. Thankfully, Django’s collectstatic management command (python manage.py collectstatic) addresses this. It iterates through STATICFILES_FINDERS, copying all static files from application static folders and those listed in STATICFILES_DIRS into the directory specified by STATIC_ROOT. This mirrors the development server’s static file resolution logic and consolidates all static assets for your web server.

Remember to run collectstatic in your production environment!

Misstep 8: Relying on Default STATICFILES_STORAGE and Django Template Loaders in Production

STATICFILES_STORAGE

Let’s discuss asset management in production. Implementing an “assets never expire” policy (read more about it here) can significantly enhance user experience. The goal is to have browsers cache your static files for extended periods, reducing server load and improving page speed. Users should ideally download assets only once.

While achievable with simple Nginx configuration, cache invalidation becomes crucial. If assets are cached indefinitely, how do you handle updates to your logo, fonts, JavaScript, or even a menu item’s color? The solution is to generate unique URLs and filenames for static files on each deployment.

This can be achieved by employing ManifestStaticFilesStorage as your STATICFILES_STORAGE (note: hashing is active only in DEBUG=false mode) and running the collectstatic command. This minimizes asset requests to your production site, leading to faster loading times.

Cached Django Template Loader

Another handy feature is Django’s cached template loader, which avoids reloading and parsing template files on every render. Template parsing is resource-intensive, and doing it on every request (the default behavior) can be detrimental in production environments handling a high volume of requests.

Refer to the cached.Loader configuration section for a practical example and details on implementing this. Avoid using this loader during development, as it doesn’t dynamically reload from the filesystem. Every template change would require a project restart (python manage.py startapp), which can be disruptive. However, it’s ideal for production environments.

Misstep 9: Writing Plain Python Scripts for Utilities or Automated Tasks

Django offers a convenient feature called Management Commands. Leverage it instead of resorting to raw Python scripts for project utilities.

Also, explore the Django Extensions package—a collection of custom Django extensions. Someone might have already solved your problem! It includes numerous commands for common tasks.

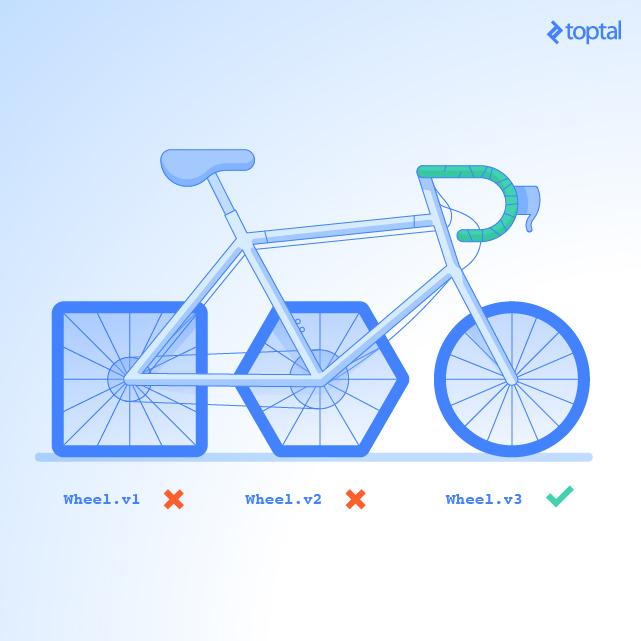

Misstep 10: Reinventing the Wheel

Django and Python boast a vast ecosystem of ready-made solutions. Before writing something from scratch, a quick Google search might reveal a feature-rich existing solution.

Embrace simplicity. Google first! If you find a suitable package, install, configure, extend, and integrate it into your project. And of course, contribute back to open source whenever you can.

To get you started, here are some of my public Django packages:

- Django Macros URL simplifies writing and understanding URL patterns in your Django applications using macros.

- Django Templates Names is a handy mix-in for effortless standardization of your CBV template names.

- django-split-settings helps organize Django settings across multiple files and directories, making overrides and modifications a breeze. It supports wildcards in file paths and allows marking settings files as optional.

Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY)!

As a firm believer in the DRY principle, I created Django skeleton—a convenient tool with a host of useful features out of the box:

- Docker images for development and production, managed seamlessly by docker-compose, simplifying the orchestration of multiple containers.

- A straightforward Fabric script for production deployments.

- Configuration for the Django Split Settings package, including settings for both base and local sources.

- Webpack integration, where only the

distfolder is collected by Django duringcollectstatic. - Pre-configured essential Django settings and features like cached templates in production, hashed static files, integrated debug toolbar, logging, and more.

This ready-to-use Django skeleton can jumpstart your next project, saving you valuable time and effort. It also includes basic Webpack configuration with pre-installed SASS for handling .scss files.