Refactoring with Codemods and jscodeshift

Have you ever found yourself using find-and-replace across your project to modify JavaScript files? If you’re savvy, you might have even utilized regular expressions with capturing groups, particularly for large codebases. However, regex has its limitations. For substantial code alterations, you need a developer who understands the code’s context and is prepared to undertake a potentially tedious and error-prone process.

This is where “codemods” come into play.

Essentially, codemods are scripts designed to rewrite other scripts. Consider them as a find-and-replace mechanism capable of reading and writing code. They can be used to align source code with a team’s coding standards, implement widespread changes after an API update, or even automatically fix existing code when a breaking change is introduced in your public package.

This article delves into “jscodeshift,” a toolkit for codemods, through the creation of three increasingly complex codemods. By the end, you’ll have a solid understanding of jscodeshift and be ready to develop your own codemods. We’ll work through three exercises showcasing fundamental yet powerful uses of codemods. You can find the source code for these exercises on my github project.

Introducing jscodeshift

The jscodeshift toolkit enables you to process multiple source files through a transform, replacing them with the output. Within the transform, you parse the source code into an abstract syntax tree (AST), make the desired changes, and then regenerate the source code from the modified AST.

Jscodeshift provides an interface that wraps around the recast and ast-types packages. recast handles the conversion between source code and AST, while ast-types manages low-level interactions with AST nodes.

Setting Up jscodeshift

Begin by installing jscodeshift globally using npm.

| |

While jscodeshift offers runner options and an opinionated test setup for easy testing with Jest, we’ll prioritize simplicity for now:

jscodeshift -t some-transform.js input-file.js -d -p

This command processes input-file.js using the some-transform.js transform and displays the results without modifying the original file.

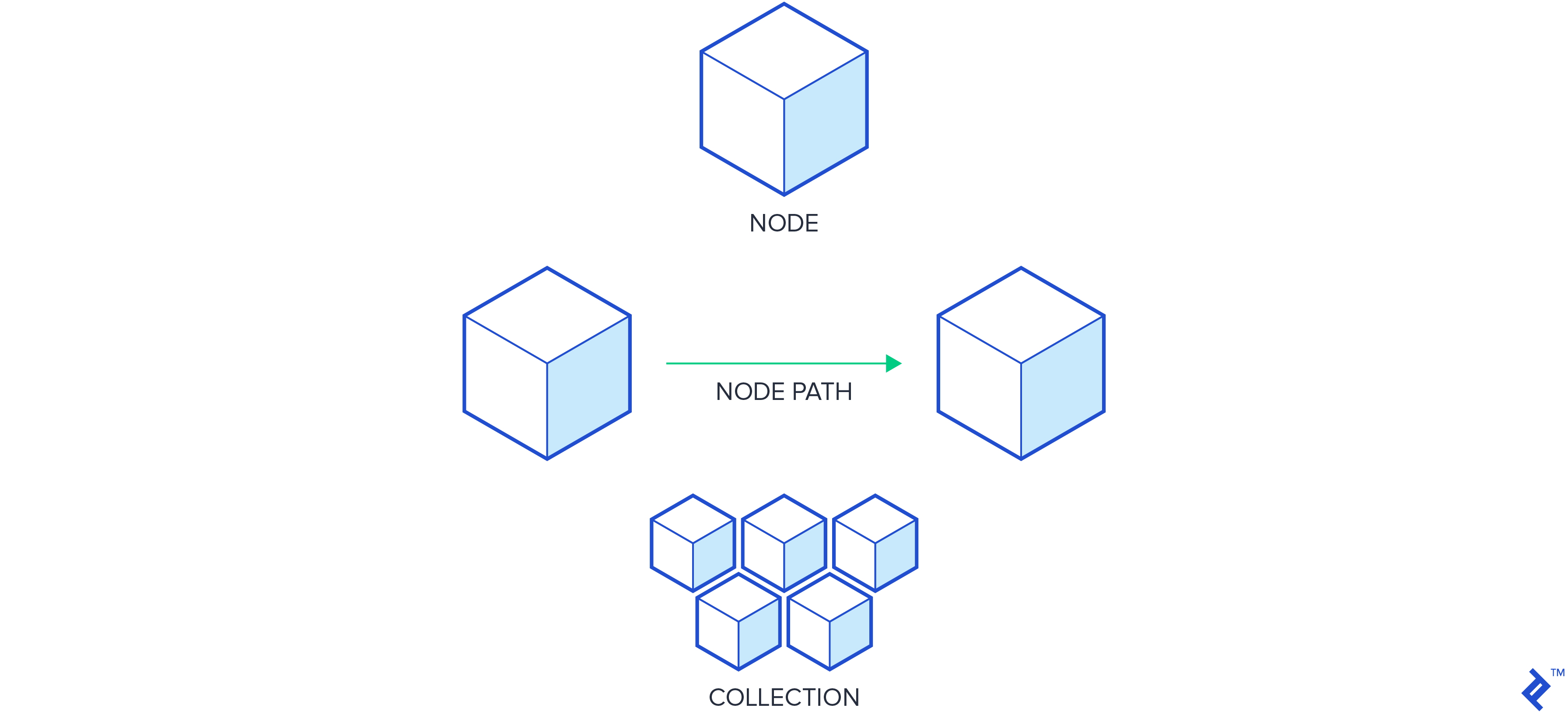

Before proceeding, it’s crucial to grasp the three primary object types used in the jscodeshift API: nodes, node-paths, and collections.

Understanding Nodes

Nodes are the fundamental components of the AST, often called “AST nodes.” They are simple objects, visible when inspecting code with AST Explorer, and lack methods.

Working with Node-paths

Node-paths, provided by ast-types, are wrappers around AST nodes that facilitate traversal of the AST. Since nodes lack inherent information about their parent or scope, node-paths provide this context. The wrapped node can be accessed using the node property, and various methods are available to manipulate the underlying node. Node-paths are often simply referred to as “paths.”

Exploring Collections

Collections are groups of zero or more node-paths returned by the jscodeshift API when querying the AST. They offer numerous helpful methods, some of which we’ll explore.

Collections contain node-paths, which in turn contain nodes, the building blocks of the AST. Keeping this hierarchy in mind will make it easier to comprehend the jscodeshift query API.

To differentiate between these objects and their capabilities, a handy tool called jscodeshift-helper logs the object type and other essential information.

Exercise 1: Removing Console Calls

As a starting point, let’s remove calls to all console methods in our codebase. Although achievable with find-and-replace and regex, this becomes complex with multiline statements, template literals, and intricate calls, making it an ideal first example.

Create two files: remove-consoles.js and remove-consoles.input.js:

| |

| |

We’ll use the following command in the terminal:

jscodeshift -t remove-consoles.js remove-consoles.input.js -d -p

If set up properly, running this command should yield something like:

| |

While this may seem underwhelming since our transform doesn’t yet modify anything, it confirms that our setup is functional. If it doesn’t run, double-check your global jscodeshift installation. An incorrect transform execution command will result in either an “ERROR Transform file … does not exist” message or a “TypeError: path must be a string or Buffer” message if the input file is not found. Descriptive transformation errors should help pinpoint any typos.

Our desired outcome after a successful transformation is the following source code:

| |

To achieve this, we need to convert the source code into an AST, locate and remove the console calls, and then convert the modified AST back into source code. The first and last steps are straightforward:

| |

However, how do we locate and remove the console calls? Unless you possess exceptional knowledge of the Mozilla Parser API, a tool like AST Explorer can be helpful for visualizing the AST. Paste the content of remove-consoles.input.js into AST Explorer, and you’ll see the corresponding AST. To manage the volume of data, consider hiding location data and methods.

As you can see, calls to console methods are represented as CallExpressions. To find them in our transform, we’ll use jscodeshift’s queries, keeping in mind the distinction between Collections, node-paths, and nodes:

| |

The line const root = j(fileInfo.source); returns a collection containing a single node-path, which wraps the root AST node. We can use the collection’s find method to search for descendant nodes of a particular type, such as:

| |

This returns another collection of node-paths containing only the CallExpression nodes. However, this is too broad. Our transforms might process numerous files, so precision is key. The naive find above would find every CallExpression, not just the console calls, including:

| |

For greater specificity, we can provide a second argument to .find: An object containing additional parameters that each node must meet to be included in the results. AST Explorer shows that our console.\* calls have the following structure:

| |

Knowing this, we can refine our query with a specifier that targets only the desired CallExpressions:

| |

Now that we have an accurate collection of console call sites, we can remove them from the AST using the collection’s remove method. Our remove-consoles.js file now looks like this:

| |

Running our transform using jscodeshift -t remove-consoles.js remove-consoles.input.js -d -p should now output:

| |

Looking good! Since our transform now modifies the underlying AST, .toSource() generates a different string from the original. The -p option displays the result, and a tally of dispositions for each processed file is shown. Removing the -d option would replace the content of remove-consoles.input.js with the transform’s output.

While our first exercise is complete, the code might seem awkward. To improve readability, jscodeshift allows chaining in most cases. We can rewrite our transform as follows:

| |

Much better! In this exercise, we wrapped the source code, queried for a collection of node-paths, modified the AST, and regenerated the source code. Let’s move on to something more intriguing.

Exercise 2: Replacing Imported Method Calls

Imagine a “geometry” module with a “circleArea” method that has been deprecated in favor of “getCircleArea.” Finding and replacing these with /geometry\.circleArea/g would be simple, but what if the module is imported with a different name? For instance:

| |

How can we determine that we need to replace g.circleArea instead of geometry.circleArea? We need context, which is where codemods shine. Let’s create two files: deprecated.js and deprecated.input.js.

| |

| |

Now, run the codemod:

jscodeshift -t ./deprecated.js ./deprecated.input.js -d -p

The output should indicate that the transform ran without making changes.

| |

We need to know the name used for our imported “geometry” module. Let’s examine the AST in AST Explorer. Our import has this form:

| |

We can specify an object type to find a collection of nodes like this:

| |

This gives us the ImportDeclaration for “geometry.” From there, we can dig down to find the local name assigned to the imported module. Note an important point that often causes confusion:

Note: root.find() returns a collection of node-paths. .get(n) retrieves the node-path at index n in that collection, while .node accesses the actual node (what we see in AST Explorer). Remember, the node-path mainly provides information about the node’s scope and relationships, not the node itself.

| |

This allows us to dynamically determine the name used for our “geometry” module. Next, we need to find and change its usage. AST Explorer shows that we need to look for MemberExpressions like this:

| |

However, we need to account for the potentially different module name:

| |

With this query, we get a collection of call sites to our old method. We can then use the collection’s replaceWith() method to swap them out. replaceWith() iterates through the collection, passing each node-path to a callback function. The AST node is then replaced with whatever is returned from the callback.

After the replacement, we generate the source code as usual. Here’s our complete transform:

| |

Running the source code through the transform shows that the deprecated method call in the “geometry” module has been changed, while the rest remains untouched:

| |

Exercise 3: Changing a Method Signature

We’ve covered querying for specific node types, removing nodes, and altering nodes. Now, let’s create entirely new nodes.

Imagine a method signature that has become unwieldy due to numerous individual arguments:

car.factory('white', 'Kia', 'Sorento', 2010, 50000, null, true);

We want to refactor this to accept an object containing these arguments:

| |

Let’s create the transform and input file:

| |

| |

Our command to run the transform is jscodeshift -t signature-change.js signature-change.input.js -d -p. Here are the steps:

- Find the local name of the imported module.

- Find all call sites to the

.factorymethod. - Read all arguments being passed.

- Replace the call with a single argument containing an object holding the original values.

Based on previous exercises and AST Explorer, the first two steps are straightforward:

| |

To read the arguments, we’ll use the replaceWith() method on our collection of CallExpressions. This will replace node.arguments with a new single argument: an object.

Let’s test with a simple object:

| |

Running this (jscodeshift -t signature-change.js signature-change.input.js -d -p) results in an error:

| |

We can’t directly insert plain objects into AST nodes. We need builders.

Node Builders

Builders, provided by ast-types and exposed through jscodeshift, enable proper creation of new nodes. They ensure correct node creation, which might seem restrictive at times but ultimately benefits us. Two key points to remember:

- All available AST node types are defined in the

deffolder of the ast-types github project repository, primarily incore.js. - Builders exist for all AST node types but use the [camel-cased](https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/x2dbyw72(v=vs.71) version of the node type, not the pascal-case name (as seen in the ast-types source).

Using AST Explorer with our desired result, we can piece this together. We want our new argument to be an ObjectExpression with several properties. Looking at the type definitions:

| |

Therefore, the code to build an AST node for { foo: 'bar' } would be:

| |

Plugging this into our transform:

| |

Running this gives us:

| |

Now that we know how to create AST nodes, we can iterate through the old arguments and generate a new object:

| |

Running the transform (jscodeshift -t signature-change.js signature-change.input.js -d -p) shows the updated signatures:

| |

Conclusion

While reaching this point required effort, the benefits of codemods for large-scale refactoring are substantial. Jscodeshift excels at parallel processing, making it possible to apply complex transformations across massive codebases quickly. As you become more comfortable with codemods, you can reuse existing scripts (like the react-codemod github repository) or write your own, improving efficiency for you, your team, and your users.