The field of computer vision and deep learning has seen remarkable advancements in supervised learning over the last decade.

In supervised learning, humans manually label a massive amount of data. This labeled data is then fed into models, allowing them to decipher intricate relationships between data points and their corresponding labels. This process enables the models to predict labels for new, unseen data. Deep learning models, known for their complexity, often require massive datasets to achieve optimal performance. The impressive strides in deep learning can be attributed to the continuous improvement of hardware and the abundance of large, human-labeled datasets.

However, a significant limitation of supervised deep learning is its heavy reliance on vast amounts of labeled data for training. This dependence poses a challenge as obtaining such extensive labeled datasets can be impractical and costly across various domains. While obtaining labeled data can be challenging, we often have access to vast quantities of unlabeled datasets, particularly in the realms of images and text. Consequently, it becomes essential to explore methods for leveraging these untapped data resources for learning.

Utilizing Pretrained Models for Transfer Learning

In scenarios where we lack access to large labeled datasets, a common strategy is to employ transfer learning. Transfer learning involves leveraging the knowledge gained from a similar task to address the problem at hand. Practically, this often translates to initializing a deep neural network with weights learned from a similar task, rather than starting with random weight initialization. Subsequently, we further train this model on the available labeled data to solve the specific task.

Transfer learning empowers us to train models effectively, even with datasets containing only a few thousand examples, often achieving commendable performance. Three primary approaches can be adopted when implementing transfer learning with pretrained models:

1. Feature Extraction

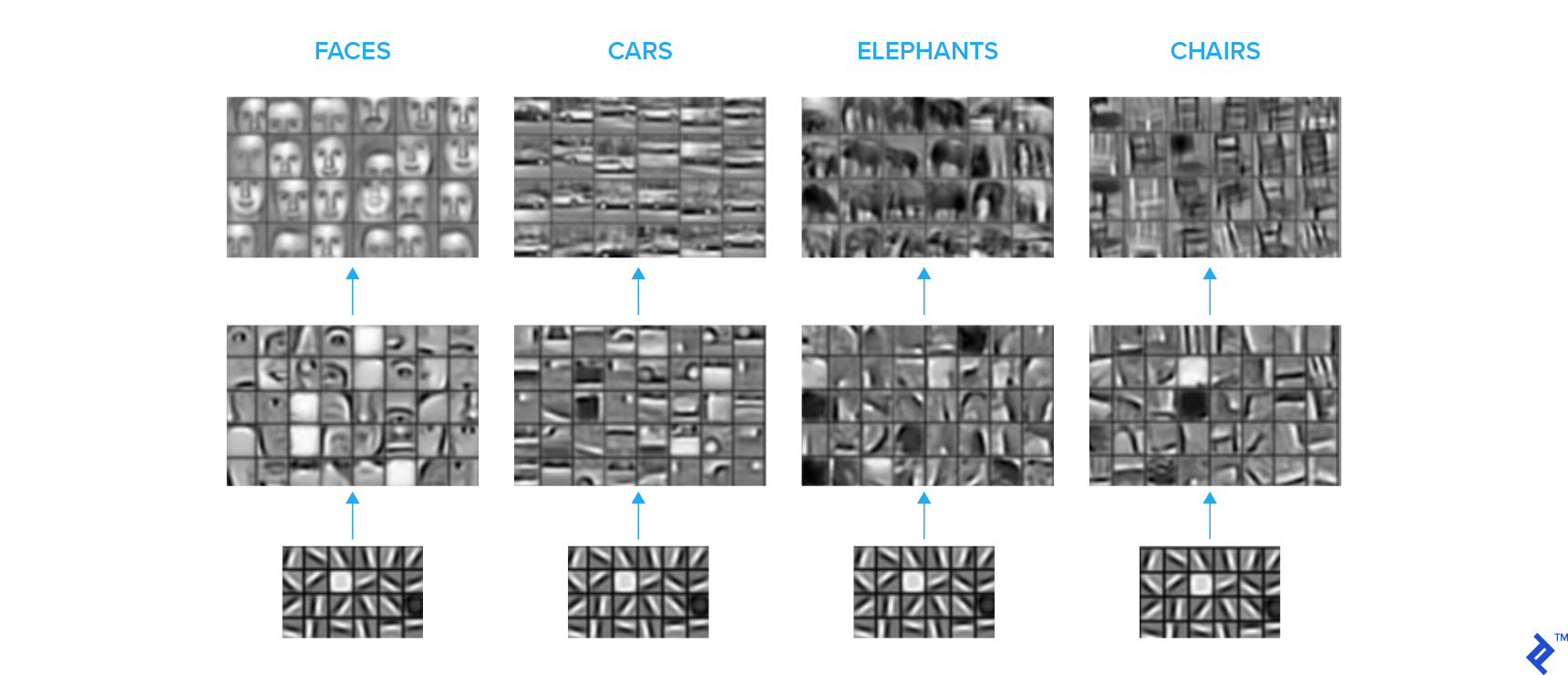

The layers at the end of a neural network typically perform the most complex and task-specific computations, making them less transferable to other tasks. Conversely, initial layers learn fundamental features like edges and shapes, which are easily transferable across different tasks.

To illustrate this concept, consider the following sets of images that demonstrate the features captured by convolutional kernels at various levels within a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). A hierarchical representation emerges, where initial layers detect basic shapes, while higher layers gradually learn to recognize more complex semantic concepts.

A common practice is to utilize a model pretrained on extensive labeled image datasets (such as ImageNet). We remove the fully connected layers at the end and replace them with new, task-specific fully connected layers, configured according to the desired number of classes. During training, the transferred layers are frozen, while the new layers are trained on the available labeled data for the specific task.

In this approach, the pretrained model acts as a feature extractor, and the added fully connected layers function as a simple classifier. This method is robust against overfitting because the number of trainable parameters is kept relatively small, making it effective when labeled data is limited. Determining the threshold for what constitutes a “very small dataset” can be subjective and depends on factors like the problem’s complexity and the size of the pretrained model. As a general rule of thumb, I would recommend this strategy for datasets containing a few thousand images.

2. Fine-tuning

An alternative approach involves transferring layers from a pretrained network and then training the entire network on the available labeled data. This method requires more labeled data compared to feature extraction, as the entire network’s parameters are being trained, increasing the risk of overfitting if data is limited.

3. Two-stage Transfer Learning

This technique, a personal favorite of mine, often produces the most favorable outcomes. In this approach, we freeze the transferred layers and initially train only the newly added layers for a few epochs. Subsequently, we unfreeze the transferred layers and fine-tune the entire network.

Directly fine-tuning the entire network without the initial training of final layers can lead to the propagation of detrimental gradients from randomly initialized layers to the pretrained base network. Additionally, fine-tuning necessitates a smaller learning rate, which is naturally addressed in this two-stage approach.

The Importance of Semi-supervised and Unsupervised Methods

The aforementioned transfer learning techniques work well for many image classification tasks due to the availability of large, diverse image datasets like ImageNet. These datasets encompass a significant portion of potential image variations, making the learned weights transferable to various custom image classification tasks. Furthermore, the availability of off-the-shelf pretrained networks trained on such datasets simplifies the process.

However, transfer learning from datasets like ImageNet may not be effective when the target task involves images with significantly different distributions. For instance, if your task deals with grayscale images from a medical imaging device, directly applying ImageNet weights might not be optimal, and you would require more than a few thousand labeled images for satisfactory performance.

In such cases, you might have access to a substantial amount of unlabeled data relevant to your problem. Therefore, learning from unlabeled data becomes paramount. Often, the unlabeled dataset is considerably larger and more diverse than even the biggest labeled datasets.

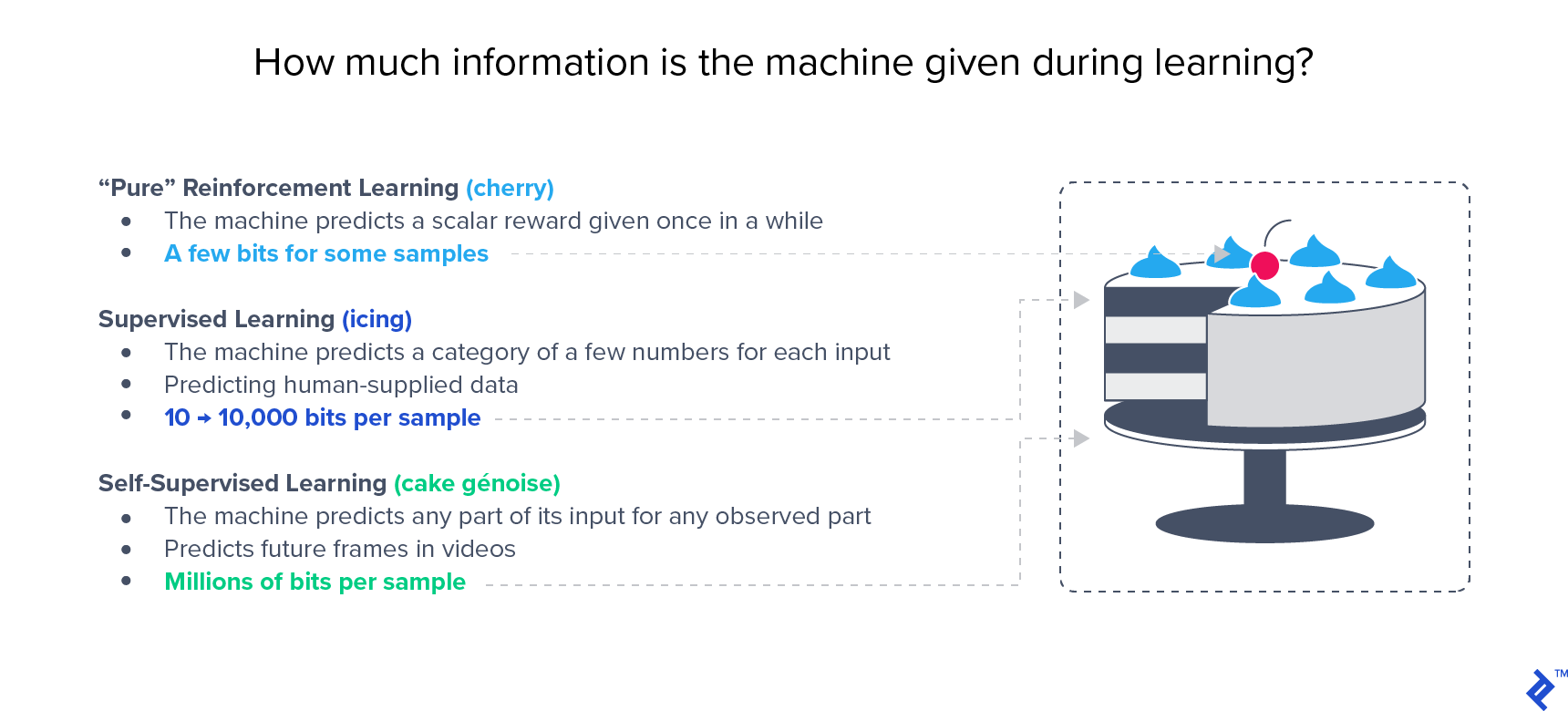

Notably, semi-supervised approaches, which leverage both labeled and unlabeled data, have demonstrated superior performance compared to solely supervised approaches on benchmarks like ImageNet. Yann LeCun’s renowned cake analogy aptly emphasizes the significance of unsupervised learning:

Semi-supervised Learning

Semi-supervised learning utilizes both labeled and unlabeled data for training. It is particularly beneficial when you have a limited amount of labeled data and a large amount of unlabeled data. While techniques exist for simultaneous learning from both types of data, we will focus on a two-stage approach: first, unsupervised learning on unlabeled data, followed by transfer learning using one of the strategies outlined earlier to address the classification task.

The term “unsupervised learning” can be misleading in this context. These approaches aren’t truly unsupervised as there is a guiding signal for weight learning; however, this signal is derived from the data itself, leading to the alternative term “self-supervised learning.” Both terms are often used interchangeably in the literature to refer to the same concept.

The prominent techniques in self-supervised learning can be categorized based on how they generate this supervisory signal from the data:

Generative Methods

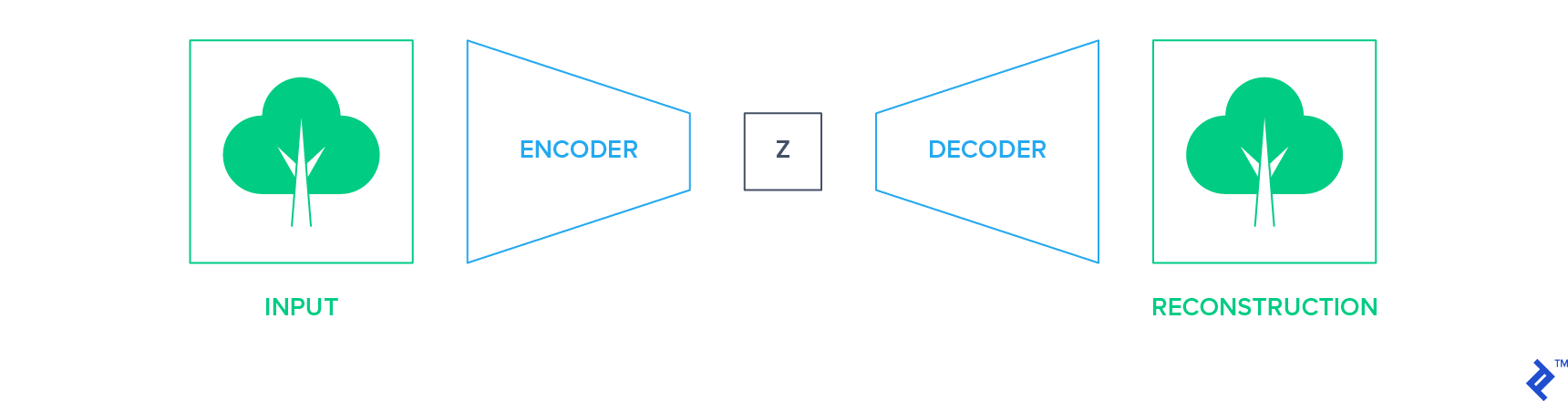

Generative methods focus on accurately reconstructing data after it passes through a bottleneck. Autoencoders exemplify this approach. They compress the input into a lower-dimensional representation using an encoder network and then reconstruct the original input using a decoder network.

In this framework, the input data itself serves as the supervisory signal (label) for training the network. The trained encoder network can then be extracted and utilized as a starting point for building your classifier, employing one of the transfer learning techniques discussed earlier.

Similarly, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), another form of generative networks, can be pretrained on unlabeled data. The discriminator network from the GAN can then be adapted and fine-tuned for the classification task.

Discriminative Methods

Discriminative methods train a neural network to learn an auxiliary task. This auxiliary task is carefully chosen so that the supervisory signal can be generated directly from the data itself, eliminating the need for manual annotation.

Examples of such tasks include predicting the relative positions of image patches, colorizing grayscale images, or identifying geometric transformations applied to images. Let’s delve deeper into two of these tasks:

Predicting Relative Positions of Image Patches

In this method, patches are extracted from an image and arranged in a grid, resembling a jigsaw puzzle. The positions of these patches are then shuffled, and this shuffled input is fed into the network. The network’s objective is to predict the correct location of each patch within the grid. The supervisory signal, in this case, is the actual position of each patch.

By learning to solve this jigsaw puzzle, the network gains an understanding of the relative structure and orientation of objects within an image. Moreover, it learns the continuity of low-level visual features like color. Results indicate that the features learned through this jigsaw puzzle task are highly transferable to tasks like image classification and object detection.

Learning Geometric Transformations Applied to Images

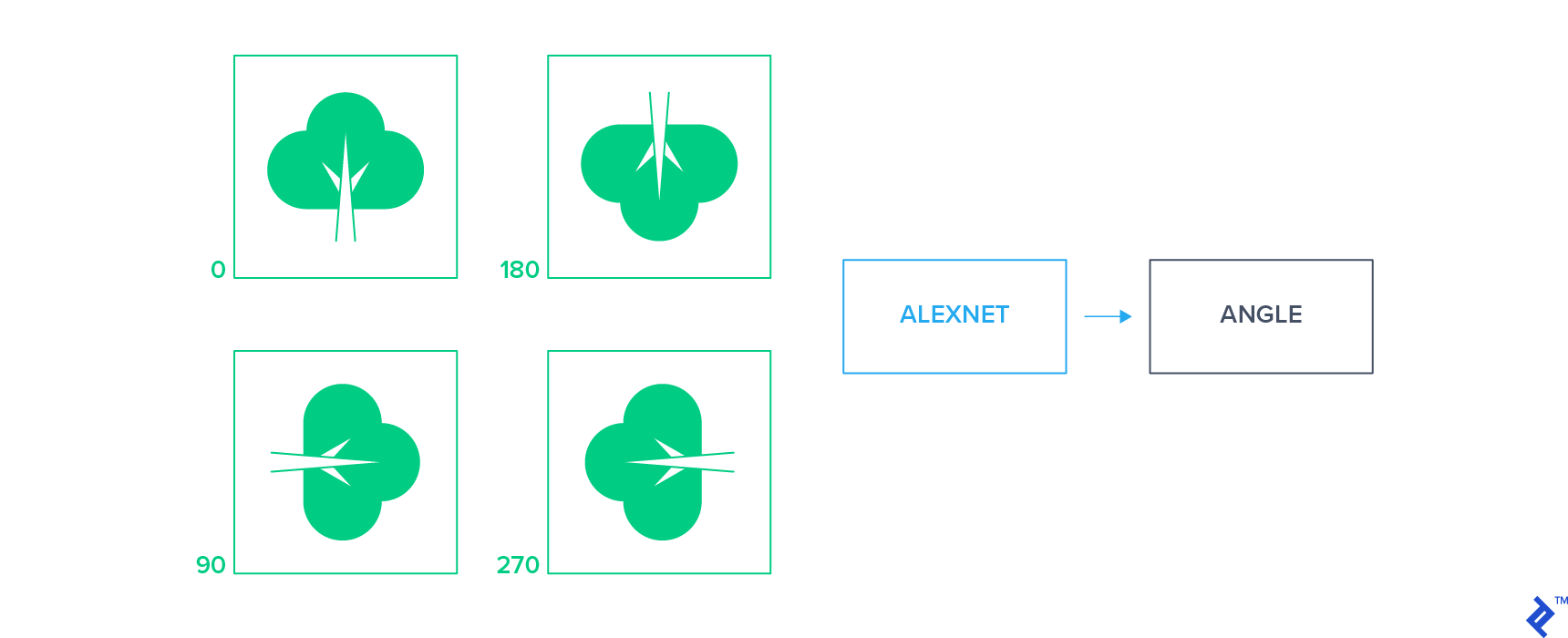

In this approach, a limited set of geometric transformations is applied to the input images. A classifier is then trained to predict the applied transformation by analyzing the transformed image alone. For instance, we can apply 2D rotations to unlabeled images, creating a set of rotated images. The network is then tasked with predicting the rotation angle applied to each image.

This straightforward supervisory signal compels the network to learn object localization within an image and understand their orientation. Features learned through this approach have proven highly transferable, yielding state-of-the-art performance for classification tasks in semi-supervised settings.

Similarity-based Approaches

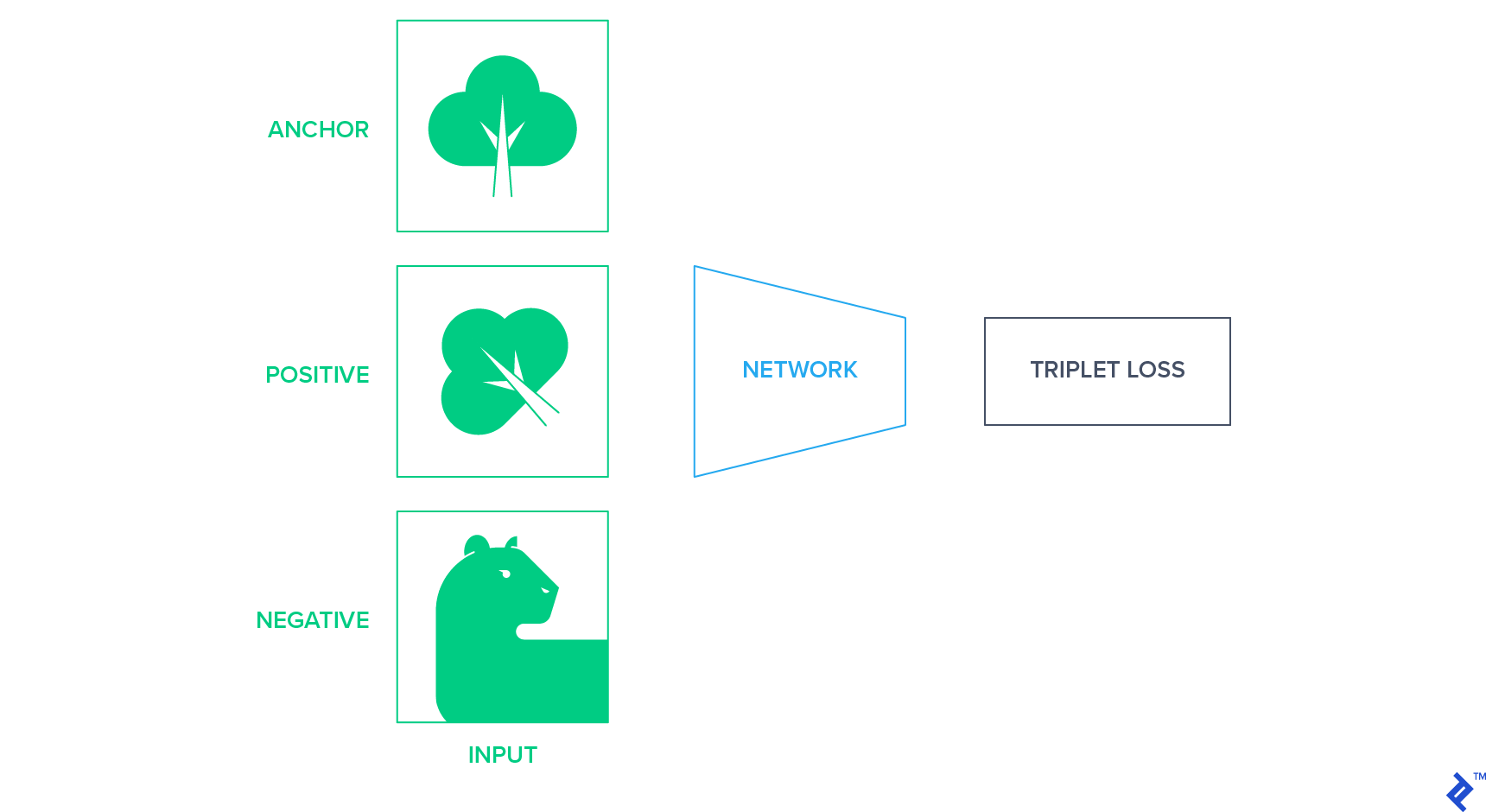

These methods involve projecting images into a fixed-size representation space, ensuring that similar images are clustered closer together while dissimilar images are farther apart. One way to achieve this is by utilizing siamese networks based on triplet loss. Triplet loss aims to minimize the distance between semantically similar images. It operates using an anchor, a positive example, and a negative example. The objective is to bring the positive example closer to the anchor than the negative example in terms of Euclidean distance within the latent space. The anchor and positive example belong to the same class, while the negative example is chosen randomly from other classes.

In the context of unlabeled data, where class labels are unknown, we need a strategy to generate these triplets (anchor, positive, negative). One approach is to apply a random affine transformation to the anchor image, using the transformed image as the positive example. A different image is then randomly chosen as the negative example.

Experiment

Let me illustrate the potential of unsupervised pretraining for image classification through an experiment I conducted. This experiment served as my semester project for a Deep Learning class course I took with Yann LeCun at NYU last spring.

- Dataset. The dataset comprised 128,000 labeled examples, evenly split between training and validation sets. Additionally, we had access to 512,000 unlabeled images. The dataset contained a total of 1,000 classes.

- Unsupervised pre-training. We pretrained a AlexNet network for rotation classification using extensive data augmentation for 63 epochs. We adhered to the hyperparameters outlined in the original paper.

- Classifier training. Features were extracted from the fourth convolutional layer, and three fully connected layers were added. These layers were randomly initialized and trained with a decreasing learning rate schedule. Early stopping was implemented to prevent overfitting.

- Whole network fine-tuning. Finally, we fine-tuned the entire network using all labeled data. Both the pretrained feature extractor and the classifier, trained separately before, were fine-tuned together with a small learning rate for 15 epochs.

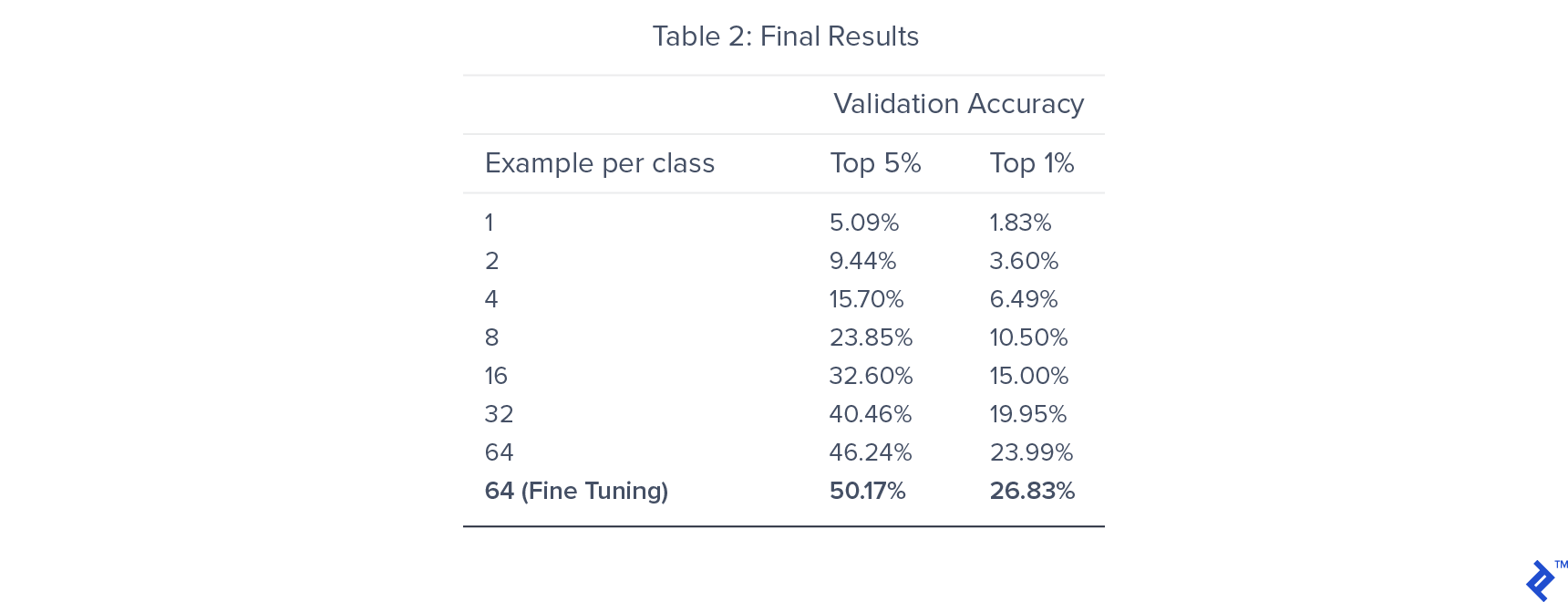

To understand the impact of training data size, we trained seven models, each using a different number of labeled training examples per class.

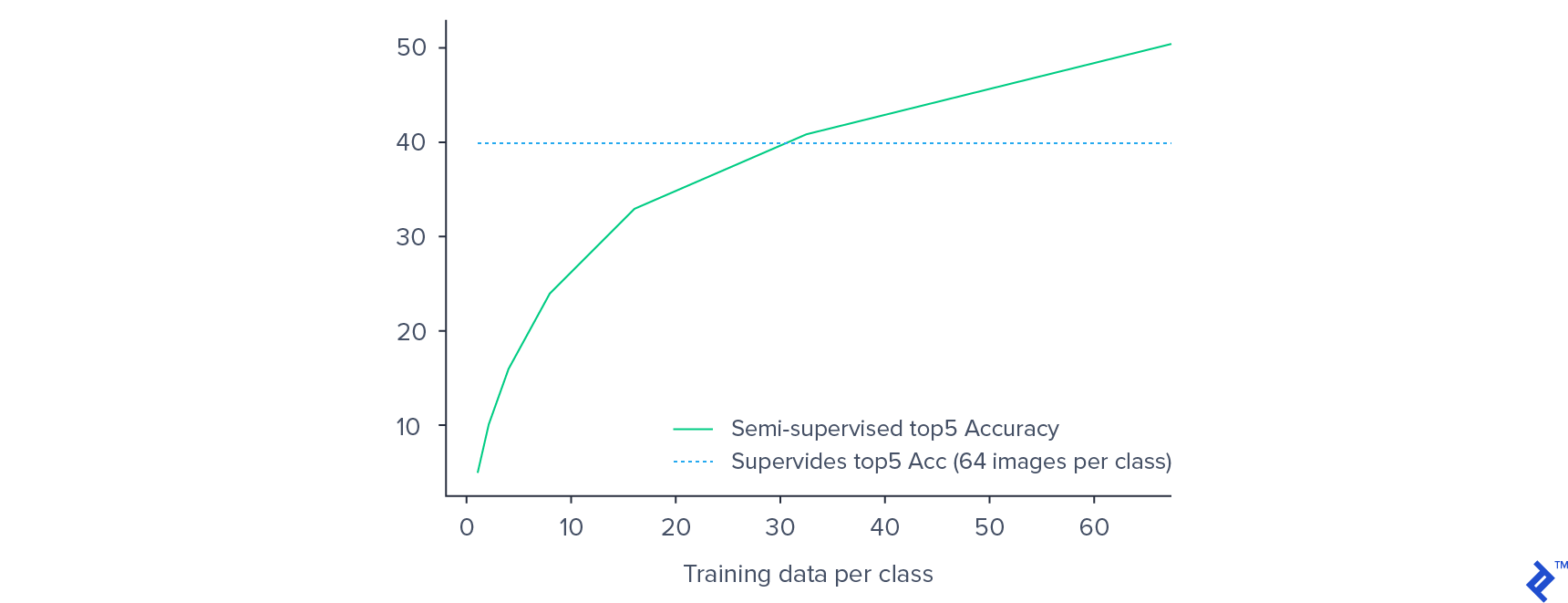

We achieved an 82% accuracy rate for the rotation classification pretraining task. For the classifier training phase, the top 5% accuracy plateaued around 46.24%, while fine-tuning the entire network yielded a final accuracy of 50.17%. By incorporating pretraining, we surpassed the performance of a solely supervised approach, which achieved 40% top 5 accuracy.

As anticipated, the validation accuracy decreased as the amount of labeled training data decreased. However, this performance drop was less pronounced than what is typically observed in purely supervised settings. For instance, reducing the training data by 50% (from 64 to 32 examples per class) resulted in only a 15% decrease in validation accuracy.

Remarkably, our semi-supervised model, trained on only 32 examples per class, outperformed the supervised model trained on 64 examples per class. These findings provide compelling evidence for the potential of semi-supervised approaches in image classification, particularly when dealing with limited labeled datasets.

Conclusion

Unsupervised learning is a powerful paradigm that can significantly enhance performance when working with limited labeled data. Despite being a relatively nascent field, unsupervised learning is poised to gain increasing traction in computer vision. This growth will be driven by its ability to learn from abundant and easily accessible unlabeled data, paving the way for more efficient and effective learning in the future.