When a lead developer on a fascinating and cutting-edge project proposed migrating from AngularJS to Elm, my initial reaction was one of bewilderment.

Our existing AngularJS application was well-structured, thoroughly tested, and performing well in production. A rewrite using Angular 4, a logical upgrade path from AngularJS, seemed like a more intuitive choice, as did frameworks like React or Vue. Elm, on the other hand, seemed like an obscure, niche language, relatively unknown in the development community.

At that time, my knowledge of Elm was nonexistent. Having now gained experience with Elm, particularly through our transition from AngularJS, I believe I can articulate the reasoning behind that “why.”

This article delves into the advantages and disadvantages of Elm, exploring how its unique concepts can effectively address the challenges faced by front-end web developers. For a more tutorial-focused introduction to Elm, you can refer to this blog post.

Elm: A Purely Functional Approach to Web Development

For developers accustomed to Java or JavaScript and who consider it the intuitive way to write code, learning Elm can be a paradigm shift.

The syntax, with its absence of braces and prevalence of arrows and triangles, might appear unusual.

While the lack of curly braces might be manageable, the absence of traditional code blocks and loops like ‘for’ loops might seem perplexing. Scope can be defined using ’let’ blocks, but traditional code blocks and loops are absent in Elm.

Elm distinguishes itself as a purely functional, strongly typed, reactive, and event-driven language specifically designed for building web clients.

This unique combination of features might initially raise doubts about its practicality for programming.

However, these very characteristics culminate in a powerful and effective paradigm for programming and developing robust software.

Embracing Pure Functionality

Modern versions of Java or ECMAScript 6 might give the impression of supporting functional programming, but it’s merely a superficial implementation.

These languages still provide a plethora of non-functional constructs, tempting developers to deviate from a purely functional approach. The true difference becomes apparent when you’re restricted to functional programming, forcing you to experience its intuitive nature.

In Elm, functions reign supreme. Record names, union type values, and even operators like plus (+) and minus (-) are all functions. Functions are composed of partially applied functions passed as arguments.

The defining characteristic of a purely functional language is not the presence of functional constructs, but the absence of their non-functional counterparts. This constraint compels developers to adopt a purely functional mindset.

Elm draws inspiration from established functional programming principles, resembling languages like Haskell and OCaml in its approach.

The Strength of Strong Typing

Developers familiar with Java or TypeScript will understand the concept of strong typing, where every variable must have a single, well-defined type.

However, there are nuances. Similar to TypeScript, type declarations are optional in Elm, with the compiler inferring types if not explicitly defined. However, unlike TypeScript, Elm does not have an “any” type.

While Java supports generic types, Elm handles them more elegantly. Generics in Java, being a later addition, require explicit specification using the somewhat clunky <> syntax.

In contrast, Elm embraces generics by default unless specified otherwise. To illustrate, let’s consider a method that takes a list of a specific type and returns a number. In Java, it would be:

| |

In Elm, the equivalent code would be:

| |

Although optional, explicitly declaring types is highly recommended. While the Elm compiler prevents operations on mismatched types, humans, especially when learning, are more prone to such errors. The example above, with type annotations, would look like this:

| |

The practice of declaring types on separate lines might seem unusual initially but becomes second nature over time.

A Language Tailored for the Web Client

Elm’s compilation target is JavaScript, making it executable within web browsers.

Unlike general-purpose languages like Java or JavaScript with Node.js, Elm focuses specifically on building the client-side of web applications. Elm goes beyond handling business logic (typically done in JavaScript) by encompassing the presentational layer (HTML) within its functional paradigm.

This is achieved through a structured, framework-like approach known as The Elm Architecture.

Embracing Reactivity

The Elm Architecture is inherently reactive, ensuring that any changes to the model are immediately reflected in the view without the need for explicit DOM manipulation.

This reactive nature is similar to frameworks like Angular or React. However, Elm’s implementation is distinct. The key lies in the signatures of the ‘view’ and ‘update’ functions:

| |

In Elm, the view is not merely an HTML representation of the model. It’s HTML imbued with the ability to generate messages of type ‘Msg’, where ‘Msg’ is a custom-defined union type.

Standard page events, such as user interactions, can trigger messages. Upon receiving a message, Elm internally invokes the ‘update’ function, passing the message along with the current model. The ‘update’ function then updates the model based on the received message and the current model state. This updated model is then internally rendered back to the view, ensuring consistency between the model and the view.

Event-Driven Nature

Elm, like JavaScript, is event-driven. However, unlike Node.js, where asynchronous actions rely on individual callbacks, Elm groups events into distinct sets of messages defined within a single message type. Similar to union types, these message types can carry various information.

There are three primary sources of events that can generate messages: user interactions within the ‘Html’ view, the execution of commands, and external events to which the application has subscribed. This explains why ‘Html’, ‘Cmd’, and ‘Sub’ all include ‘msg’ as an argument. This generic ‘msg’ type must remain consistent across all three definitions and should match the one passed to the ‘update’ function (in the previous example, it was ‘Msg’ with a capital ‘M’), where all message processing is centralized.

Source Code of a Realistic Example

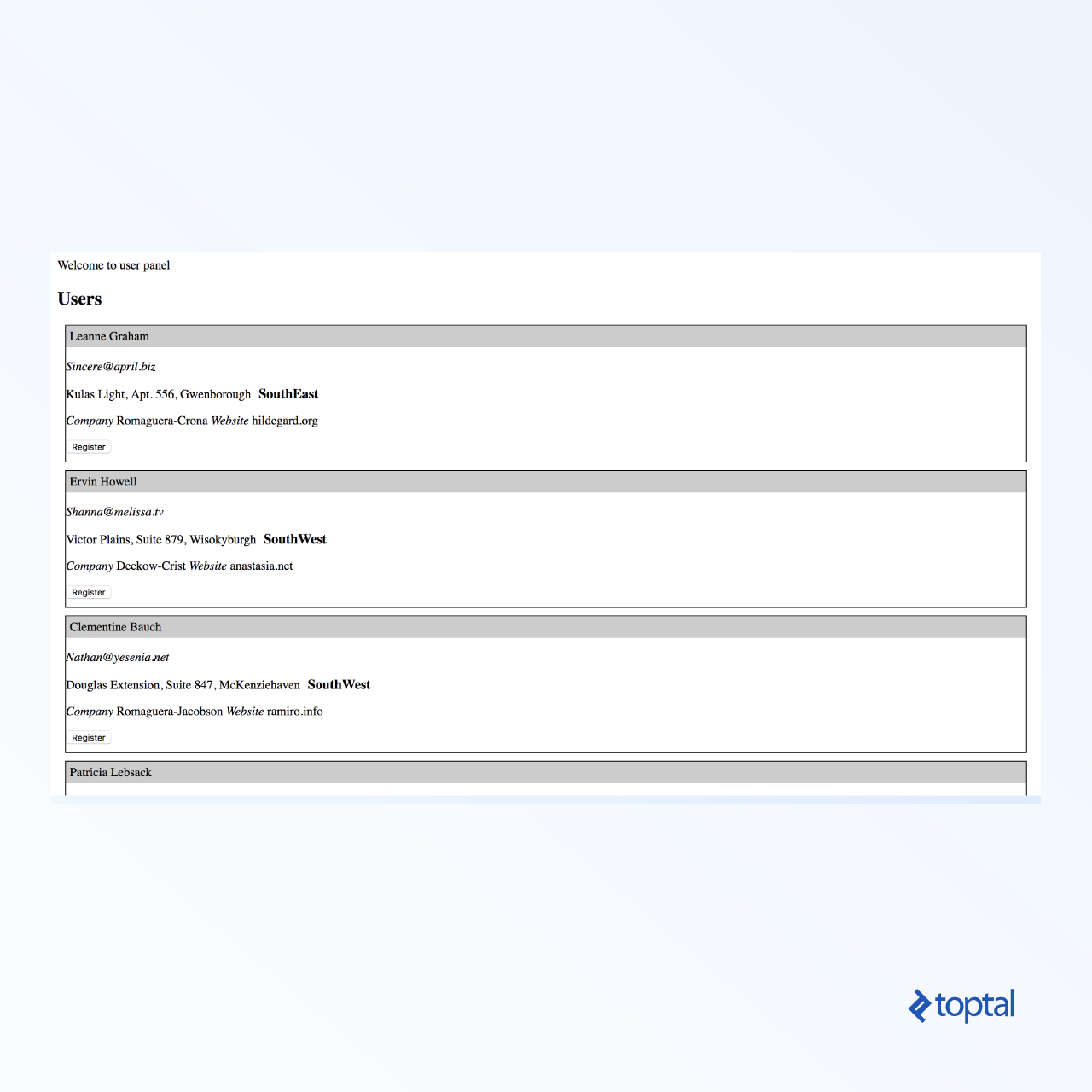

This GitHub repository provides a complete example of an Elm web application. While simple, it showcases common functionalities used in everyday client-side programming: fetching data from a REST endpoint, encoding and decoding JSON data, utilizing views, messages, and other structures, interacting with JavaScript, and the process of compiling and bundling Elm code using Webpack.

The application displays a list of users fetched from a server.

To simplify the setup and demonstration process, Webpack’s development server handles both the bundling of all components, including Elm, and serving the user list.

The example intentionally distributes functionality between Elm and JavaScript to highlight their interoperability. This approach allows developers to experiment with Elm, gradually migrating existing JavaScript code or adding new features in Elm, ensuring that the application functions seamlessly with both Elm and JavaScript. This gradual adoption is often more practical than rewriting an entire application from scratch in Elm.

In this example, the Elm portion is initialized with configuration data from JavaScript, fetches the user list, and displays it. Let’s assume some user actions are already implemented in JavaScript; invoking such an action in Elm simply dispatches a call back to the JavaScript implementation.

This example also demonstrates concepts and techniques discussed in the next section.

Applying Elm Concepts

Let’s explore how some of Elm’s unique concepts can be applied to real-world scenarios.

The Versatility of Union Types

Union types are a cornerstone of Elm, offering a clean and elegant way to model situations where structurally different data needs to be processed by the same algorithm.

Consider pagination, where links for the previous, next, and individual page numbers are displayed. How can you effectively represent which link a user clicked?

One approach might involve multiple callbacks for previous, next, and page number clicks. Alternatively, boolean flags could indicate the click target, or specific integer values (e.g., negative numbers, zero) could be assigned special meanings. However, none of these solutions accurately models this type of user event.

Elm provides an elegant solution using union types:

| |

This union type can then be used as a parameter for one of the messages:

| |

The update function can then use a ‘case’ statement to handle different ’nextPage’ types:

| |

This approach results in clean and expressive code.

Creating Multiple Map Functions with <|

Many modules provide a ‘map’ function with variations to accommodate a specific number of arguments. For example, ‘List’ includes ‘map’, ‘map2’, and so on, up to ‘map5’. However, handling functions with more arguments, such as six, requires a workaround.

This workaround leverages the <| function as a parameter, along with partial functions, to apply arguments and generate intermediate results.

For simplicity, let’s assume ‘List’ only has ‘map’ and ‘map2’, and we want to apply a function that takes three arguments to three lists.

The implementation would look like this:

| |

Let’s assume we have a function ‘foo’ that multiplies its numeric arguments:

| |

Calling map3 foo [1,2,3,4,5] [1,2,3,4,5] [1,2,3,4,5] would return [1,8,27,64,125] : List number.

Let’s break down the process.

Firstly, in partialResult = List.map2 foo list1 list2, ‘foo’ is partially applied to each pair in ’list1’ and ’list2’, resulting in [foo 1 1, foo 2 2, foo 3 3, foo 4 4, foo 5 5]. This is a list of functions, each expecting one argument (as the first two are already applied) and returning a number.

Next, in List.map2 (<|) partialResult list3, it expands to List.map2 (<|) [foo 1 1, foo 2 2, foo 3 3, foo 4 4, foo 5 5] list3. The <| function is applied to each pair from these two lists. For instance, the first pair results in (<|) (foo 1 1) 1, which is equivalent to foo 1 1 <| 1, further simplifying to foo 1 1 1, which evaluates to ‘1’. Similarly, the second pair becomes (<|) (foo 2 2) 2, then foo 2 2 2, producing ‘8’, and so on.

This technique proves particularly useful with ‘mapN’ functions, especially when decoding JSON objects containing numerous fields, as ‘Json.Decode’ provides these functions up to ‘map8’.

Efficiently Extracting Values from Maybes

Suppose you have a list of ‘Maybe’ values and want to extract only the elements containing actual values. For example, given the list:

| |

You want to obtain [1,3,6,7] : List Int. This can be achieved with a single line of code:

| |

Let’s understand why this works.

‘List.filterMap’ expects a function as its first argument, specifically one with the signature (a -> Maybe b). This function is applied to each element of the provided list (the second argument). The resulting list is then filtered to remove any ‘Nothing’ values, and finally, the actual values are extracted from the remaining ‘Maybe’ elements.

By supplying ‘identity’ in our example, the resulting list remains [Just 1, Nothing, Just 3, Nothing, Nothing, Just 6, Just 7]. After filtering, it becomes [Just 1, Just 3, Just 6, Just 7], and upon value extraction, we get the desired [1,3,6,7].

Creating Custom JSON Decoders

As your JSON decoding (deserialization) requirements become more complex, building custom decoders might become challenging, especially when dealing with intricate JSON structures.

Let’s illustrate with two examples.

First, imagine incoming JSON with fields ‘a’ and ‘b’ representing the sides of a rectangle. You only want to store the area in your Elm object.

| |

Individual fields are decoded using the field int decoder, and both values are passed to the function provided in map2. Since multiplication (*) is also a function that accepts two arguments, it can be directly used here. The resulting areaDecoder decodes the input and returns the result of the applied function, in this case, a * b.

In the second example, a status field in the incoming JSON can be null, an empty string, or any other string. The operation is considered successful only if the status is “OK.” You want to store this as True; otherwise, it should be False. The decoder would look like this:

| |

Let’s test it with some JSON:

| |

The key lies in the function passed to ‘andThen’. This function receives the result of the previous nullable string decoder (a ‘Maybe String’), transforms it into the desired format, and returns the result as a decoder using ‘succeed’.

Key Takeaway

These examples demonstrate that functional programming might not feel immediately intuitive for developers accustomed to Java or JavaScript. Mastering it requires time and experimentation. ’elm-repl’ can be a helpful tool for practicing and understanding the return types of expressions.

The previously mentioned example project includes additional custom decoder and encoder examples that can further aid in understanding.

Why Choose Elm?

Elm’s distinct nature sets it apart from other client-side frameworks, offering unique advantages and disadvantages.

Let’s start with the positives.

Unified Development Experience

Elm eliminates the need for separate HTML and JavaScript, providing a unified language for both logic and presentation.

No more context switching between languages or dealing with the complexities of templating languages.

Elm offers a single, consistent syntax and full language expressiveness.

Consistency and Clarity

With functions as the foundation and a limited set of structures, Elm enforces a high degree of consistency. There’s no ambiguity regarding method definitions or numerous ways to iterate through lists.

Many languages have debates about idiomatic code.

In Elm, if it compiles, it’s likely written in the “Elm way.” If it doesn’t, it certainly isn’t.

Expressiveness Through Conciseness

Despite its conciseness, Elm’s syntax is highly expressive.

This is achieved through union types, explicit type declarations, and a functional style, encouraging the use of smaller, focused functions. The result is code that is largely self-documenting.

A World Without Null

Long-time Java or JavaScript developers might consider ’null’ an unavoidable aspect of programming. Despite encountering ‘NullPointerException’s and ‘TypeError’s, the root cause, the existence of ’null’, is often overlooked.

Elm challenges this assumption. The absence of ’null’ not only eliminates runtime null reference errors but also encourages cleaner code by forcing developers to explicitly handle cases where a value might be absent, reducing technical debt and preventing issues down the line.

Increased Confidence in Code Correctness

While syntactically valid JavaScript programs are easy to write, their correctness is not always guaranteed without thorough testing.

Elm takes a different approach. Static type checking and enforced ’null’ checks might increase compilation time, especially for beginners. However, successful compilation significantly increases the likelihood of the program behaving as expected.

Performance as a Priority

Performance can be crucial for web applications. Elm’s speed contributes to a responsive user experience, which is essential for user satisfaction and product success. As tests show attest, Elm is remarkably fast.

Elm’s Advantages Over Traditional Frameworks

Traditional web frameworks often offer powerful tools but come with complex architectures, numerous concepts, and specific rules for their use. Mastering them can be time-consuming. There are controllers, components, directives, compilation phases, runtime considerations, services, factories, custom templating languages within directives, situations requiring manual $scope.$apply() calls for view updates, and more.

While Elm’s compilation to JavaScript is also complex, developers are shielded from these complexities. They can focus on writing Elm code, leaving the intricacies of the compilation process to the compiler.

Why Not Choose Elm?

Despite its merits, Elm also has its drawbacks.

Documentation Needs Improvement

Elm’s documentation is a significant shortcoming. The official tutorials provide a basic overview but leave many questions unanswered.

The official API reference is even more lacking, with many functions lacking detailed explanations or examples. Statements like “If this is confusing, work through the Elm Architecture Tutorial. It really does help!” in the official API documentation are far from ideal.

Hopefully, this will be addressed soon.

Elm’s adoption will likely be hindered by poor documentation, especially for developers coming from Java or JavaScript backgrounds who might find its concepts and functions unfamiliar. Comprehensive documentation with ample examples is crucial for wider acceptance.

Formatting and Whitespace Quirks

While the absence of curly braces and parentheses, coupled with whitespace-based indentation, can improve code readability (as seen in Python), the creators of elm-format seem to have taken it a step further.

Elm code often ends up being more vertical than horizontal due to double line spaces and expressions and assignments spanning multiple lines. Code that would be a concise one-liner in C can easily turn into a multi-screen affair in Elm.

While this might be beneficial for those compensated based on lines of code, aligning code with expressions starting hundreds of lines earlier can be challenging.

Working with Records

Records in Elm can be cumbersome. Modifying record fields involves awkward syntax, and there’s no straightforward way to modify nested fields or reference fields dynamically by name. Using accessor functions generically can lead to typing issues.

In JavaScript, records (objects) are fundamental, easily constructed, accessed, and modified. Even JSON is essentially a serialized record. Given their prevalence in web development, Elm’s limitations in handling records can be a notable drawback if records are your primary data structure.

Increased Verbosity

Elm generally requires more code compared to JavaScript.

The lack of implicit type conversion for string and number operations results in numerous int-float conversions, toString calls (often requiring parentheses or function application symbols for correct argument matching), and the need for Html.text to receive strings. Extensive use of ‘case’ expressions is necessary to handle ‘Maybe’s, ‘Result’s, and various other types.

This verbosity stems from Elm’s strict type system, which is arguably a worthwhile trade-off.

JSON Handling Overhead

The difference in verbosity becomes particularly apparent when handling JSON. What can be achieved with a simple JSON.parse() in JavaScript can easily translate to hundreds of lines of Elm code.

While mapping between JSON and Elm structures is necessary, the requirement to write both decoders and encoders for the same JSON data can be tedious, especially for REST APIs exchanging objects with numerous fields.

Conclusion

Having explored Elm, it’s time to address the perennial questions in software development: Is it better than the alternatives? Should we use it in our projects?

The first question is subjective. Elm might excel and be a superior choice over other web client frameworks in certain scenarios but fall short in others. It offers unique advantages that can make front-end development more robust and manageable compared to alternatives.

To avoid the cliché “it depends” answer to the second question, the short answer is: Yes. Despite its shortcomings, the confidence Elm provides in terms of code correctness alone justifies its use.

Elm is also enjoyable to work with, offering a fresh perspective for developers accustomed to traditional web development paradigms.

Realistically, switching an entire application to Elm or starting a new project entirely in Elm might not always be feasible. Leveraging its interoperability with JavaScript allows for gradual adoption, starting with specific interface components or functionalities written in Elm. This allows you to evaluate its suitability for your needs before expanding its use or deciding against it. And who knows, you might just fall in love with the world of functional web programming.