Web developers understand the challenges of deploying and updating applications on self-managed servers. Platform as a service (PaaS) offers a simpler approach, albeit with higher costs and less flexibility. While PaaS can be convenient, deploying applications on unmanaged servers is sometimes necessary or preferable. Automating this process may seem daunting, but creating a straightforward tool can be surprisingly easy, saving time and effort.

Developers employ various methods for automating web application deployment, often tailored to specific technology stacks. For instance, the steps involved in automatically deploying a PHP website differ from deploying a Node.js web application. Generic solutions like Dokku, known as buildpacks, accommodate a broader range of technology stacks.

This tutorial explores the fundamental concepts behind building a simple deployment automation tool using GitHub webhooks, buildpacks, and Procfiles. The prototype program’s source code, available on GitHub, will serve as a reference.

Getting Started with the Web Applications

We’ll create a simple Go program to automate web application deployment. Don’t worry if you’re not familiar with Go; the code is straightforward. You can also adapt it to another language.

Ensure you have Go installed. The steps outlined in the official documentation provides installation instructions.

Download the tool’s source code by cloning the GitHub repository. This facilitates following along with the code snippets, which are labeled with their respective filenames. Feel free to try it out.

Using Go minimizes external dependencies. Our program only requires Git and Bash on the server. Go’s statically linked binaries enable easy compilation, upload, and execution. Other languages might require substantial runtime environments or interpreters. Well-written Go programs are also resource-efficient, consuming minimal CPU and RAM, which is desirable for such tasks.

GitHub Webhooks

GitHub Webhooks allow configuring repositories to emit events upon changes or specific user actions. Users can subscribe to these events and receive notifications via URL invocations.

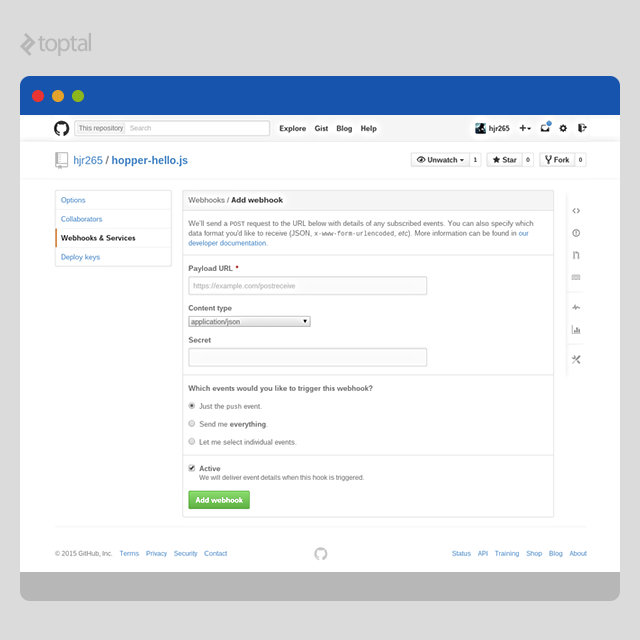

Creating a webhook is straightforward:

- Access your repository’s settings page.

- Select “Webhooks & Services” from the left navigation menu.

- Click the “Add webhook” button.

- Provide the URL and an optional secret for payload verification.

- Configure other options as needed.

- Submit the form by clicking the “Add webhook” button.

GitHub provides comprehensive extensive documentation on Webhooks, detailing their functionality and payload information for various events. We’re particularly interested in the “push” event, triggered upon pushes to any repository branch.

Buildpacks

Buildpacks have become a standard, widely used by PaaS providers. They specify the stack configuration before application deployment. Writing buildpacks is usually straightforward, and many existing ones can be found online.

If you’ve used PaaS like Heroku, you’re likely familiar with buildpacks. Heroku offers extensive documentation about the structure of buildpacks and a list of some well built popular buildpacks.

Our automation program will utilize compile scripts from buildpacks to prepare the application. For instance, a Node.js buildpack might parse package.json, download the appropriate Node.js version, and fetch NPM dependencies. To simplify things, our prototype will have limited buildpack support, assuming Bash-based scripts designed for fresh Ubuntu installations. You can extend this later for more specific requirements.

Procfiles

Procfiles are text files defining the different process types within your application. Simple applications often have a single “web” process handling HTTP requests.

Procfiles are simple to write. Define one process type per line using the format “process-name: command”:

| |

For example, a Node.js application might start its web server with “node index.js”. Create a file named “Procfile” in your code’s root directory with the following content:

| |

Our program expects applications to define process types in Procfiles for automatic startup after code retrieval.

Handling Events

Our program requires an HTTP server to receive incoming POST requests from GitHub. We’ll designate a URL path for handling these requests. The function handling these payloads will resemble this:

| |

We begin by verifying the event type. Since we only care about “push” events, others are ignored. Even if configured for only “push” events, expect a “ping” event to confirm successful webhook setup on GitHub.

Next, we read the entire request body, calculate its HMAC-SHA1 using the webhook’s secret, and verify the payload’s integrity against the signature in the request header. For simplicity, our program skips validation if no secret is configured. Note that reading the entire body without a size limit is generally not recommended.

The incoming payload is then unmarshalled using a struct from the GitHub client library for Go. Since it’s a “push” event, we can use the PushEvent struct. We then employ the standard JSON encoding library to unmarshal the payload into an instance of the struct. After some sanity checks, the application update function is invoked.

Updating Application

Upon receiving an event notification, we can update our application. We’ll examine a straightforward implementation with room for improvement. However, it provides a basic automated deployment process.

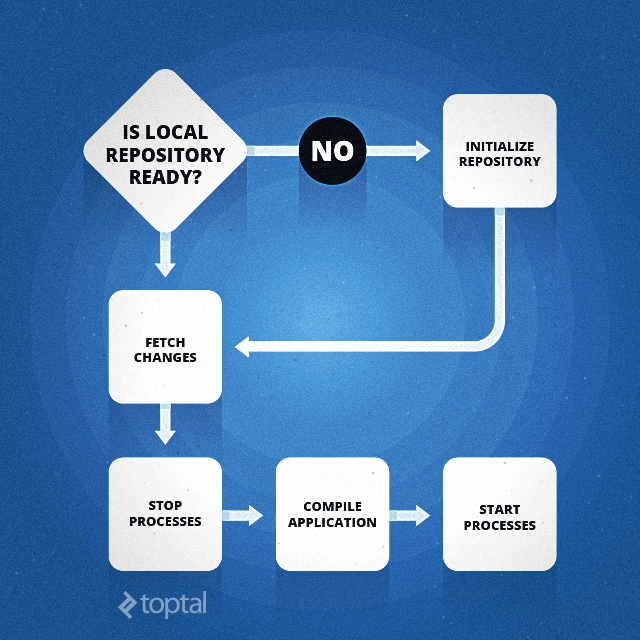

Initializing Local Repository

The process starts by checking if this is the first deployment attempt by looking for the local repository directory. If absent, we initialize it:

| |

The App struct’s method initializes the local repository:

- Create a directory for the local repository if it doesn’t exist.

- Execute “git init” to create a bare repository.

- Add the remote repository’s URL to the local repository and name it “origin”.

Fetching changes becomes simple with an initialized repository.

Fetching Changes

Fetching changes involves executing a single command:

| |

Performing “git fetch” this way prevents issues with Git’s inability to fast-forward in certain scenarios. While forced fetches shouldn’t be your go-to solution, it gracefully handles situations requiring force pushes to the remote repository.

Compiling Application

Using buildpack scripts for compilation simplifies our task:

| |

We remove the previous application directory (if any), create a new one, and check out the master branch’s contents into it. The configured buildpack’s “detect” script checks if we can handle the application. A “cache” directory is created for the buildpack’s compilation process, if needed. Since this directory persists, creation might be unnecessary if it exists from a previous compilation. We then run the buildpack’s “compile” script to prepare the application for launch. Properly implemented buildpacks handle caching and reuse previously cached resources.

Restarting Application

Our implementation stops old processes before compilation and starts new ones afterward. While straightforward, it presents opportunities for improvement, such as ensuring zero downtime during updates. We’ll stick with the simpler approach:

| |

Our prototype stops and starts processes by iterating over an array of nodes, each representing an instance of the application. We track each node’s process state and maintain individual log files. Before starting, each node is assigned a unique port, incrementing from a base port number:

| |

This might seem more involved. Let’s break down the code into four parts. The first two are within the “NewNode” function, which populates a “Node” struct and spawns a Go routine to manage the corresponding process. The other two are the “Start” and “Stop” methods of the “Node” struct.

Starting or stopping a process involves passing a “message” through a channel monitored by the per-node Go routine. A message to start or stop is sent. Using a single Go routine avoids race conditions.

The Go routine enters an infinite loop, waiting for messages on the “stateCh” channel. Upon receiving a start request (inside “case StateUp”), it executes the command using Bash, configuring environment variables and redirecting output streams to a log file.

To stop a process (inside “case StateDown”), it’s terminated. Consider adding a SIGTERM signal and a grace period before forcefully killing the process for a more graceful shutdown.

The “Start” and “Stop” methods simplify message passing. Unlike “Start”, which returns after sending the start message, “Stop” waits for process termination.

Combining It All

Finally, we connect everything within the program’s main function. This involves loading and parsing the configuration, updating the buildpack, attempting the initial application update, and starting the web server to listen for GitHub’s “push” events:

| |

Since buildpacks are simple Git repositories, “UpdateBuildpack” (implemented in buildpack.go) performs “git clone” and “git pull” as needed to update the local copy.

Trying It Out

If you haven’t cloned the repository yet, do it now. Compile the program if you have Go installed:

| |

These commands create a directory named “hopper,” set it as GOPATH, fetch the code and libraries, and compile the program. The binary will be located in “$GOPATH/bin”.

Create a simple web application for testing. For convenience, a “Hello, world” Node.js application is available at another GitHub repository, which you can fork.

Upload the compiled binary to a server and create a configuration file in the same directory:

| |

The “core.addr” option sets the internal web server’s HTTP port. In this example, “:26590” makes the program listen for “push” events at “http://{host}:26590/hook”. When configuring the webhook, replace “{host}” with your server’s domain or IP. Ensure the port is open if using a firewall.

Next, set the buildpack’s Git URL. Here, we’re using Heroku’s Node.js buildpack.

Under “app”, set “repo” to your application’s GitHub repository. In this case, it’s “hjr265/hopper-hello.js” for the example application hosted at “https://github.com/hjr265/hopper-hello.js".

Configure environment variables and the number of type of processes needed. Lastly, set a secret for verifying “push” event payloads.

Start the automation program on the server. If everything is set up correctly (including deploy SSH keys for repository access), it will fetch the code, prepare the environment, and launch the application.

In the GitHub repository, set up a webhook to emit “push” events and point it to “http://{host}:26590/hook”, replacing “{host}” accordingly.

To test, make changes to the example application and push to GitHub. The automation tool will update the repository, compile the application, and restart it.

Conclusion

Experience shows this is highly beneficial. Our prototype might not be production-ready, but it offers significant room for improvement. Enhancements include robust error handling, graceful shutdowns/restarts, and potentially using Docker for process containment.

Consider your specific needs when creating a customized automation program. Alternatively, explore numerous stable and well-established solutions available online. Regardless of your choice, this article demonstrates the potential time and effort saved by automating your web application deployment process.