Some argue that “everything comes down to ones and zeros”—but do we truly grasp how our software transforms into those bits?

Both compilers and interpreters process a raw string of program code, parsing and interpreting it. While interpreters are simpler, building a basic one (handling only addition and multiplication) proves insightful. We’ll concentrate on their shared aspects: lexing and parsing input.

The Advantages and Disadvantages of Creating Your Own Interpreter

You might wonder, What’s the issue with using a regex? While powerful, regular expressions can’t handle the complexity of source code grammars. The same applies to domain-specific languages (DSLs), such as custom authorization expressions a client might require. Even without direct application, building an interpreter provides a deeper appreciation for the work behind programming languages, file formats, and DSLs.

Manually writing accurate parsers can be complex due to numerous edge cases. That’s where tools like ANTLR come in, generating parsers for common programming languages. Additionally, parser combinator libraries allow developers to write parsers directly in their chosen language, such as FastParse for Scala and Parsec for Python.

We advise using such tools and libraries professionally to avoid redundant effort. However, understanding the intricacies and possibilities of building an interpreter from scratch helps developers utilize these solutions more effectively.

Interpreter Component Overview

An interpreter comprises multiple stages:

- A lexer transforms a character sequence (plain text) into a token sequence.

- A parser then processes the token sequence, generating an abstract syntax tree (AST) based on formal grammar rules.

- An interpreter executes the AST of the source code directly, without prior compilation.

Instead of a complete, integrated interpreter, we’ll explore each component and common issues through separate examples. Ultimately, the user code will resemble this:

| |

Following the three stages, this code should calculate and display Result is: 19. We’re using Scala for its:

- Conciseness, allowing ample code on screen.

- Expression-oriented nature, eliminating uninitialized/null variables.

- Type safety, with robust collections, enums, and case classes.

We’re specifically using Scala3’s optional-braces syntax (Python-like, indentation-based). However, none of the approaches are Scala-specific, and its similarity to other languages allows easy conversion. Alternatively, examples can be run online via Scastie.

Finally, the Lexer, Parser, and Interpreter sections use different example grammars. As the corresponding GitHub repo demonstrates, later examples have slightly adjusted dependencies for these grammars, but the core concepts remain consistent.

Interpreter Component 1: Lexer Creation

Let’s lex the string: "123 + 45 true * false1". It contains various token types:

- Integer literals

- A

+operator - A

*operator - A

trueliteral - An identifier,

false1

We’ll ignore whitespace between tokens in this example.

At this stage, expression validity isn’t important; the lexer simply converts the input string into a token list. (Parsing for meaning is the parser’s job.)

We’ll represent a token with:

| |

Each token has a type, textual representation, and position in the input, aiding debugging for end users.

The EOF token signifies input end. It’s not present in the source text but simplifies parsing.

Our lexer should output:

| |

Let’s analyze the implementation:

| |

Starting with an empty token list, we iterate through the string, adding tokens as encountered.

We use the lookahead character to determine the next token’s type. Note that the lookahead character isn’t always the furthest one examined. Based on it, we determine the token’s structure and use currentPos to scan all expected characters in the current token before adding it to the list.

Whitespace is skipped. Single-letter tokens are straightforward, added while incrementing the index. For integers, we manage the index.

Now, the slight complexity: identifiers versus literals. We take the longest possible match and check if it’s a literal; otherwise, it’s an identifier.

Operators like < and <= require looking ahead one more character for = before concluding it’s a <= operator, otherwise it’s just <.

With that, our lexer produces a token list.

Interpreter Component 2: Parser Creation

We need to structure our tokens—a list alone isn’t enough. We need to know:

Expression nesting, operator application order, and applicable scoping rules.

A tree structure supports nesting and ordering. First, we define rules for constructing these trees, aiming for an unambiguous parser that consistently returns the same structure for a given input.

Note: the following parser doesn’t use the previous lexer example. It’s for adding numbers, so its grammar has only two tokens, '+' and NUM:

| |

Equivalently, using a pipe character (|) for “or” like in regular expressions:

| |

Both versions have two rules: summing two exprs or defining expr as a NUM token (nonnegative integer here).

Formal grammars define these rules. They consist of: The rules themselves A starting rule (conventionally the first one) Two symbol types for rule definition: Terminals: our language’s “letters” (and other characters)—irreducible symbols forming tokens Nonterminals: intermediate parsing constructs (replaceable symbols)

Only a nonterminal can be on a rule’s left side; the right side can have both. Above, the terminals are '+' and NUM, the only nonterminal is expr. In Java, terminals are like 'true', '+', Identifier, '[', while nonterminals are like BlockStatements, ClassBody, MethodOrFieldDecl.

We’ll use a “recursive descent” parsing technique—common due to its simplicity in understanding and implementation.

A recursive descent parser utilizes one function per grammar nonterminal. It starts from the starting rule, descending and determining the applicable rule within each function. Recursion is crucial, enabling nested nonterminals! Regexes fall short here: they can’t even handle balanced parentheses. We need a more powerful tool.

A parser for the first rule might look like this (full code):

| |

The eat() function checks if the lookahead matches the expected token and advances the lookahead index. However, this won’t work yet due to grammar issues.

Grammar Ambiguity

Our grammar has an ambiguity, which might not be immediately obvious:

| |

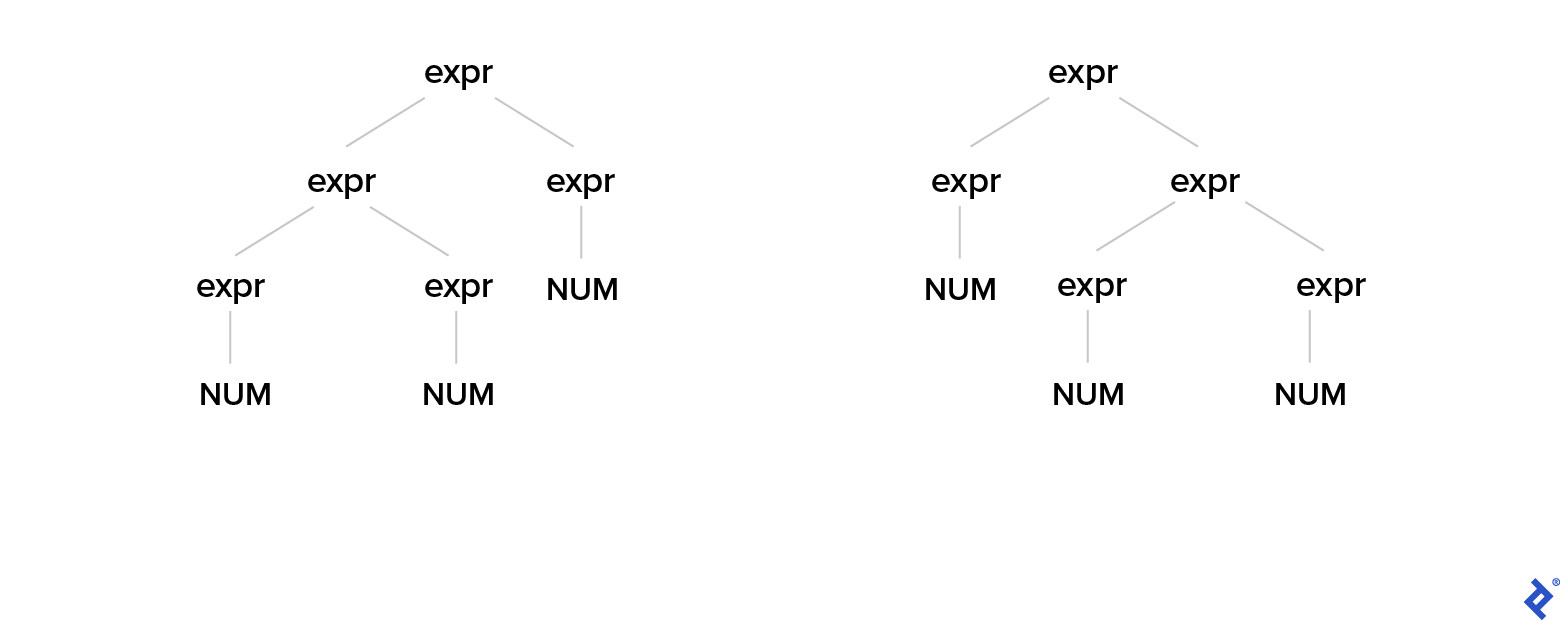

Given 1 + 2 + 3, our parser could prioritize either the left or right expr first in the AST:

We need to introduce asymmetry:

| |

The expressible expressions remain unchanged, but now it’s unambiguous: the parser consistently prioritizes the left side, making our + operation left associative (this becomes clearer in the Interpreter section).

Left-recursive Rules

However, this doesn’t solve our other issue, left recursion:

| |

We have infinite recursion, leading to a stack overflow. Parsing theory to the rescue!

Consider this grammar, with alpha as any terminal/nonterminal sequence:

| |

We can rewrite it as:

| |

Here, epsilon is an empty string—nothing, no token.

Our current grammar:

| |

Rewriting with the method above, where alpha is '+' NUM, we get:

| |

Now parsable with recursive descent. Let’s see the parser for this iteration:

| |

We use the EOF token for simplicity, ensuring at least one token in our list, avoiding empty list handling.

With a streaming lexer, we wouldn’t have an in-memory list but an iterator, requiring a marker for input end. At the end, the EOF token should be last.

Analyzing the code, an expression can be a single number. If nothing remains, the next token wouldn’t be Plus, stopping parsing. The last token would be EOF.

With more tokens, they must be like + 123, triggering recursion on exprOpt()!

AST Generation

Our parsed expression is difficult to work with as is. We could use callbacks in the parser, but that becomes cumbersome. Instead, we return an AST, a tree representing the expression:

| |

This mirrors our rules using data classes.

Our parser now returns a usable data structure:

| |

For eat(), error(), and other details, see the accompanying GitHub repo.

Simplifying Rules

Our ExprOpt nonterminal can be improved:

| |

Its grammar pattern isn’t immediately clear. We can replace this recursion:

| |

This means '+' NUM occurs zero or more times.

Our complete grammar now:

| |

And a cleaner AST:

| |

The resulting parser is the same length but more understandable. We’ve eliminated Epsilon, implied by starting with an empty structure.

We didn’t need the ExprOpt class here. We could have used case class Expr(num: Int, exprOpts: Seq[Int]), or NUM ('+' NUM)* in grammar format. Why didn’t we?

Consider multiple operators like - and *:

| |

Here, the AST needs ExprOpt to accommodate the operator type:

| |

Note: [+-*] in the grammar is like regular expressions: “one of these characters,” as we’ll soon see.

Interpreter Component 3: Interpreter Creation

Our interpreter utilizes the lexer and parser to obtain the AST of our input expression and evaluate it accordingly. Here, we’re dealing with numbers and want to calculate their sum.

In the implementation of our interpreter example, we’ll use this grammar:

| |

And this AST:

| |

(Lexer and parser implementations for similar grammars were covered; if needed, refer to the repo for this specific grammar.)

Let’s write an interpreter for the above grammar:

| |

Successfully parsing into an AST guarantees at least one NUM. We then add (or subtract) the optional numbers to our result.

The earlier note about +’s left associativity is now clear: We start from the leftmost number and add others sequentially. While seemingly trivial for addition, consider subtraction: 5 - 2 - 1 evaluates as (5 - 2) - 1 = 3 - 1 = 2, not 5 - (2 - 1) = 5 - 1 = 4!

Going beyond plus and minus, we need another rule.

Precedence

Parsing 1 + 2 + 3 is simple, but 2 + 3 * 4 + 5 poses a challenge.

Conventionally, multiplication has higher precedence than addition, but our parser doesn’t inherently know this. We can’t evaluate it as ((2 + 3) * 4) + 5, but rather as (2 + (3 * 4)) + 5.

Therefore, multiplication needs evaluation first, positioned further from the AST root to ensure evaluation before addition, requiring another layer of indirection.

Fixing a Naive Grammar

Our original left-recursive grammar lacked precedence rules:

| |

First, we add precedence rules and remove ambiguity:

| |

Then, we apply non-left-recursive rules:

| |

This yields a well-structured AST:

| |

Resulting in a concise interpreter:

| |

Again, the lexer and grammar ideas were previously covered; refer to find them in the repo if needed.

Further Steps in Interpreter Development

We haven’t addressed error handling and reporting, crucial aspects of any parser. Confusing compiler errors are frustrating for developers. Providing accurate error messages, avoiding message overload, and enabling graceful error recovery are important. Developers creating interpreters or compilers should prioritize a good user experience.

Our example lexers, parsers, and interpreters only scratch the surface of compiler and interpreter theory. Other topics include:

- Scopes and symbol tables

- Static types

- Compile-time optimization

- Static analyzers and linters

- Code formatting and pretty-printing

- Domain-specific languages

For further exploration, I recommend:

- Language Implementation Patterns by Terence Parr

- The free online book, Crafting Interpreters, by Bob Nystrom

- Intro to Grammars and Parsing by Paul Klint

- Writing Good Compiler Error Messages by Caleb Meredith

- The notes from East Carolina University’s “Program Translation and Compiling” course