Numerous factors contribute to the decision of creating a new programming language, some less apparent than others. This article will delve into these motivations and outline a strategy for constructing a language tailored for the Java Virtual Machine (JVM), maximizing the use of existing tools to streamline the development process and foster user adoption through familiarity.

This introductory piece provides a high-level overview of the strategic approach and essential tools for crafting our unique JVM language. Subsequent articles will delve into the intricacies of implementation.

Why Create Your JVM Language?

Given the abundance of programming languages, the rationale for creating another merits exploration. The answer is multifaceted.

Programming languages are diverse, encompassing general-purpose languages (GPLs) and domain-specific languages (DSLs). GPLs, like Java and Scala, offer comprehensive solutions for a broad range of problems. Conversely, DSLs excel in addressing specific problem sets. HTML and Latex exemplify this, simplifying document creation despite their limited scope.

Developing a DSL might be prudent if your work frequently revolves around a particular set of challenges. Such a language would significantly boost your productivity.

Alternatively, you might be drawn to creating a GPL to explore novel concepts, such as innovative ways to represent relationships as first class citizens or represent context.

The sheer joy of creation, the allure of novelty, and the prospect of acquiring knowledge can also be compelling motivators.

Targeting the JVM offers a pragmatic advantage, enabling the creation of a functional language with reduced effort. This is because:

- Generating bytecode ensures code portability across all JVM-compatible platforms.

- Existing JVM libraries and frameworks are readily available for utilization.

The JVM significantly lowers the barrier to language development, making it feasible in scenarios that would otherwise be impractical.

What Do You Need to Make It Usable?

Certain tools are indispensable for language utilization, including a parser and a compiler or interpreter. However, true practicality demands a comprehensive toolchain often integrated with existing tools.

Ideally, your language should enable:

- Seamless management of references to code compiled for the JVM from other languages.

- Effortless source file editing in preferred IDEs with syntax highlighting, error identification, and auto-completion.

- Compilation using familiar build systems like Maven or Gradle.

- Effortless test writing and execution as part of a continuous integration pipeline.

These features are crucial for encouraging language adoption. So, how do we achieve this? Let’s examine the necessary components.

Parsing and Compiling

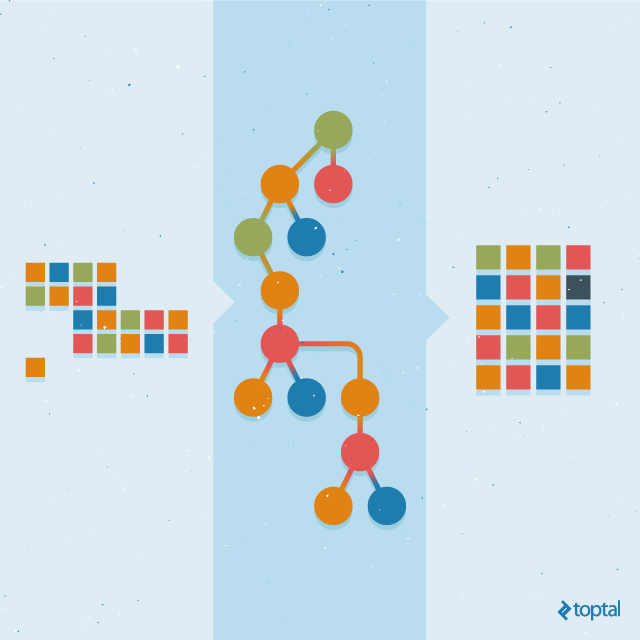

Transforming source code into a program begins with parsing, creating an Abstract-Syntax-Tree (AST) representation. This stage involves validation for syntactical and semantic errors, and symbol resolution. Finally, bytecode is generated.

The journey from source code to compiled bytecode comprises three primary phases:

- AST Construction

- AST Analysis and Transformation

- Bytecode Generation

Let’s delve into these phases.

Building an AST: Parsing is a well-trodden path. While numerous frameworks exist, ANTLR stands out due to its popularity, robust maintenance, and grammar simplification features.

Analyzing and transforming the AST: Implementing a type system, validation, and symbol resolution can be complex and labor-intensive, potentially requiring a dedicated discussion. For now, acknowledge this phase as the most demanding part of compiler development.

Producing the bytecode from the AST: This final phase is relatively straightforward. With symbol resolution and groundwork laid in the previous phase, translating individual nodes of the transformed AST to bytecode instructions becomes almost mechanical. Control structures require additional attention, as for-loops, switches, and if statements translate to conditional and unconditional jumps (gotos still lurk beneath the surface). While understanding JVM internals is necessary, the implementation itself is not overly complicated.

Integration with Other Languages

Achieving widespread adoption might lead to exclusive use of your language. However, during the initial stages, coexistence with other JVM languages is expected. Users might write classes or modules in your language within larger projects, highlighting the need for seamless integration.

Two scenarios require consideration:

- Separate module compilation for your language and others.

- Joint compilation within the same module.

The first scenario involves using code written in other languages that has been compiled separately, such as dependencies like Guava or project modules. This integration demands interpreting class files from other languages for symbol resolution and bytecode generation. Conversely, other modules might need to reuse compiled code written in your language, generally unproblematic due to Java’s compatibility. However, generating JVM-valid class files inaccessible from Java due to invalid identifier usage is possible.

The second scenario presents a greater challenge. Imagine a Java class A and a class B written in your language, each referencing the other (e.g., A extending B and B accepting A as a method parameter). The Java compiler, unable to process your language, requires a class file for B. Conversely, compiling B necessitates references to A. The solution involves a partial Java compiler, capable of interpreting a Java source file and generating a usable model for compiling class B. This necessitates parsing Java code (using tools like JavaParser) and resolving symbols. For inspiration, examine java-symbol-solver.

Tools: Gradle, Maven, Test Frameworks, CI

Developing Gradle or Maven plugins allows for seamless integration, making the use of a module written in your language transparent to the user. They can continue using familiar commands like “mvn compile” or “gradle assemble.”

However, creating Maven plugins can be arduous. Documentation is scarce, often incomprehensible, outdated, or plainly inaccurate. While Gradle plugin development appears more straightforward, it remains a consideration.

Integrating tests within the build system is crucial. This involves developing a basic unit testing framework and ensuring that running “maven test” identifies, compiles, executes tests written in your language, and reports the results to the user.

Looking at existing examples, such as the Maven plugin for Turin programming language, can be beneficial.

Successful implementation enables effortless compilation of source files written in your language and seamless integration with continuous integration services like Travis.

IDE Plugin

An IDE plugin, being the most visible tool, significantly influences user perception of your language. A well-designed plugin, with intelligent auto-completion, contextual error highlighting, and refactoring suggestions, can greatly assist users in learning and adopting the language.

The common approach involves choosing an IDE like Eclipse or IntelliJ IDEA and developing a dedicated plugin. However, this presents the most significant challenge in your toolchain for several reasons. Firstly, plugin development is IDE-specific, requiring separate efforts for Eclipse and IntelliJ IDEA. Secondly, IDE plugin development is relatively uncommon, resulting in limited documentation and a smaller community, leading to increased development time and effort. While IntelliJ IDEA forums offer better support than their Eclipse counterparts, the user base and API documentation remain limited.

An alternative solution is to utilize Xtext. Xtext, a framework for developing plugins for Eclipse, IntelliJ IDEA, and the web, offers a potentially viable alternative. Originally designed for Eclipse, its recent expansion to other platforms might present a valuable, albeit less mature, option. While developing exceptional plugins still requires utilizing native IDE APIs, Xtext simplifies the process by providing syntax error detection and completion based on the language syntax. Despite requiring manual implementation of symbol resolution and other complex features, it serves as a promising starting point. However, integrating with platform-specific libraries for Java symbol resolution remains a challenge.

Conclusions

The path to language adoption is fraught with potential pitfalls. Embracing a new language demands effort, requiring users to invest time and adapt their workflows. By minimizing friction and leveraging familiarity with existing ecosystems, you can retain users and provide them with a smoother learning curve, fostering a deeper appreciation for your language.

Ideally, users should be able to effortlessly clone a simple project written in your language, build it using standard tools like Maven or Gradle, and open it in their preferred IDE with full support for error highlighting and code completion. This streamlined experience stands in stark contrast to manually invoking compilers and resorting to basic text editors. A well-designed ecosystem surrounding your language can be a decisive factor in its adoption and, thankfully, can be achieved with reasonable effort.

While encouraging creativity in language design, prioritize familiarity and ease of use in your tooling. By leveraging existing standards and minimizing the barriers to entry, you pave the way for wider adoption and allow users to focus on experiencing the true potential of your language.

Happy language designing!