Most computer applications we use daily, from desktop and web to mobile, depend on either JSON or XML for message exchange. JSON’s widespread use today overshadows XML’s dominance just a few years ago. A simple online search comparing the two highlights a growing preference for JSON’s simplicity over XML’s perceived complexity. Numerous articles tout JSON’s superiority due to its concise nature, relegating XML to an inefficient relic. While this might suggest JSON is simply better, a deeper exploration reveals a more nuanced story.

This article aims to:

- Delve into the history of the web to understand the initial purpose behind XML and JSON.

- Analyze recent software trends to explain JSON’s surge in popularity.

A Look Back at JSON and XML

To grasp the reasons behind JSON’s widespread adoption and its perceived advantages over XML, we must journey through the evolution of the web, specifically from Web 1.0 to Web 2.0, and its impact on development trends.

The Dawn of the Web: HTML and Web 1.0

The early 1990s witnessed the rise of Web 1.0. Introduced in 1991, HTML quickly became the language of the web, embraced by universities, businesses, and government entities. HTML had its roots in SGML (“Standard Generalized Markup Language”), developed by IBM in the 1970s. Along with widespread acceptance, HTML underwent significant modification to accommodate multimedia, animation, online applications, eCommerce, and more. As an offshoot of SGML, HTML lacked a strict specification, allowing companies to freely expand it beyond its initial scope. While the race for the most popular web browser between Netscape and Microsoft fueled rapid advancement, it also fragmented the standard. This fierce competition led to a “divergence catastrophe”—both companies augmented HTML in ways that resulted in browsers supporting their unique versions, creating significant challenges for web application developers striving for interoperability.

The Need for Standardization: XML, XHTML, and Web 1.1

In the late 1990s, a group including Jon Bosak, Tim Bray, and James Clark, introduced XML—the “eXtensible Markup Language.” Similar to SGML, XML is not a markup language itself but a specification for defining them. Evolving from SGML, XML aimed to define and enforce structured content. Hailed as a game-changer in computing,1 XML aimed to “address the challenge of universal data interchange across diverse systems” (Dr. Charles Goldfarb).2 To address HTML fragmentation, the World Wide Web Committee (W3C) was established to promote industry-wide compatibility and agreement on new web standards.3 The W3C’s efforts led to XHTML, a reformulation of HTML based on XML.

XHTML, while significant in bringing attention to XML, represents only a small fraction of its capabilities.

XML empowered the industry to define, with precise semantics, custom markup languages for any application. This “strict semantic” approach allowed XML to ensure data integrity in any XML document, regardless of the specific XML sub-language. For companies developing distributed enterprise applications that interact with various systems, a markup language capable of guaranteeing data integrity was revolutionary. By leveraging XML for structured content, companies could interact with any platform, enforce data integrity in all exchanges, and systematically mitigate software risks. XML provided a universal technology for storing, exchanging, and validating data in a format readily processed by applications across platforms. For HTML, XML promised a solution to the “divergence catastrophe.”

The Rise of Server-Side Programming: Java, .NET, and XML Adoption

The early 2000s saw Sun and Microsoft dominating the web. Server-side programming languages were prominent, with web applications relying on servers generating HTML pages for browser delivery. This emphasized backend technologies, leading to the popularity of platforms like Java and C#.NET. Java, developed by Sun Microsystems, spearheaded the next generation of object-oriented programming languages, addressing cross-architecture challenges with its “write once, run anywhere”4 approach. Microsoft followed suit with .NET, C#, and the Common Language Runtime (CLR), embracing XML as the solution for data interoperability. Microsoft emerged as a strong advocate for XML, integrating it into its .NET framework. Touted as a platform for XML web services,5 .NET applications were designed to use XML for communication with other platforms. XML was adopted as Microsoft’s data interchange standard, integrated into flagship products like SQL Server and Exchange.

Asynchronous Communication Emerges: Web 1.2 and AJAX

The limitations of delivering pre-rendered HTML pages became evident as the web grew. Each user action required a new page load from the server, straining resources and bandwidth. Netscape and Microsoft addressed this with asynchronous content delivery via ActiveX and JavaScript. Conceived by the Microsoft Outlook Web Access team in 1998,6 ActiveX later found implementation in Mozilla, Safari, Opera, and other browsers through JavaScript’s XMLHttpRequest object.

AJAX emerged from the convergence of Microsoft’s ActiveX and Netscape’s JavaScript.

AJAX, short for “Asynchronous JavaScript and XML,” encompasses web technologies used to build applications that communicate with servers in the background without requiring full page reloads. Jesse James Garrett, who coined the term AJAX,7 8 outlined its core principles:

- HTML (or XHTML) and CSS for presentation.

- The Document Object Model (DOM) for dynamically displaying and interacting with data.

- XML for data interchange and XSLT for manipulation.

- The

XMLHttpRequestobject for asynchronous communication. - JavaScript to integrate these technologies.

AJAX revolutionized web development, significantly reducing server load and bandwidth consumption. The introduction of XMLHttpRequest empowered developers to implement more complex front-end logic. Google’s implementation of standards-compliant, cross-browser AJAX in Gmail (2004) and Google Maps (2005)9 and Kayak.com’s large-scale eCommerce use of AJAX in its 2004 public beta10 showcased its potential.

The Rise of Single-page Applications: Web 2.0

The adoption of AJAX as the scalable architecture for web applications ushered in the era of Web 2.0 and Single-page Applications (SPAs).11 SPAs dynamically update the current page within the browser, eliminating the need for full page reloads. This approach further reduced server load and bandwidth consumption while delivering desktop-like experiences through seamless user interactions.

Stuart Morris created one of the first SPAs in 2002 at slashdotslash.com.12 Later that year, Lucas Birdeau, Kevin Hakman, Michael Peachey, and Evan Yeh detailed a single-page application implementation in US patent 8,136,109.13, describing web browsers utilizing JavaScript for user interface display, application logic execution, and communication with a web server.

Google’s Gmail and Maps, along with Kayak’s public beta, marked a new era in web application development. AJAX-enabled browsers empowered developers to build feature-rich web applications. JavaScript’s simplicity made development accessible, leading to a surge in contributions from developers worldwide. Libraries like jQuery, which standardized AJAX behavior across browsers, further accelerated the AJAX revolution.

The Emergence of JSON

In April 2001, Douglas Crockford and Chip Morningstar sent the first JSON message. Working on AJAX applications before the term was coined, they faced limited browser support for their goals. They needed a way to transmit data to their application after page load that worked consistently across browsers.

At the time, AJAX was in its infancy, lacking a standardized XMLHttpRequest object in Internet Explorer 5 and Netscape 4. Crockford and Morningstar devised a workaround compatible with both browsers.

Their first JSON message:

| |

This HTML document with embedded JavaScript only partially resembled modern JSON. They achieved asynchronous data loading by directing an <iframe> to a URL returning an HTML document like the one above. The browser would execute the embedded JavaScript upon receiving the response, and the object literal was passed back to the main application frame, circumventing browser restrictions on sub-window access to parent windows. This “hidden frame technique,” prevalent in the late 90s before XMLHttpRequest became widely supported, offered cross-browser compatibility.14

Developers were drawn to this approach for its universality. Being pure JavaScript, it didn’t require specialized parsing. Crockford acknowledged that this use of JavaScript wasn’t entirely novel, suggesting its use at Netscape for information exchange as early as 1996.15

Recognizing its wider potential, Crockford and Morningstar named their format JSON, short for “JavaScript Object Notation.” Despite encountering resistance from clients hesitant about novel technologies lacking official specifications, they persisted. Crockford created JSON.org in 2002, publishing the JSON grammar and a reference parser implementation. This website, still active today, now prominently links to the JSON ECMA standard ratified in 2013.16. While Crockford’s direct promotion of JSON was limited, developers quickly recognized its value and contributed JSON parser implementations for various programming languages. Though rooted in JavaScript, JSON proved suitable for data exchange between diverse languages.

JSON’s Integration with AJAX

Jesse James Garrett’s 2005 blog post, coining “AJAX,” emphasized that it wasn’t a single technology but rather “a convergence of several existing technologies, each powerful in its own right, now working together in new and innovative ways."16 He described how developers could leverage JavaScript and XMLHttpRequest to build responsive and stateful applications, citing Gmail, Google Maps, and Flickr as examples. Although “X” in “AJAX” originally denoted XML, Garrett acknowledged JSON as a viable alternative. He wrote, “While XML is the most mature way to get data in and out of an AJAX client, there’s no reason you couldn’t achieve the same results using a technology like JavaScript Object Notation or any other similar means of structuring data."17

JavaScript and JSON were a natural pairing. JSON’s semantics map directly to JavaScript, making it the language’s inherent data interchange format. Developers found JSON easier to use with JavaScript, often preferring it over XML.

As JSON gained traction within the developer community, its widespread adoption had begun.

The Shift in Popularity: Why JSON Surpassed XML

Why did JSON gain favor over XML? JSON is the native data format for JavaScript, a language that has skyrocketed in popularity over the last decade, leading to the creation of more JSON messages than any other format. Using JSON for data exchange in JavaScript applications is almost a given, as alternatives introduce unnecessary complexity. JSON’s rise is intrinsically linked to JavaScript’s ascent as the go-to language for application development, offering ease of use and native integration.

The prevalence of JavaScript in online discussions is evident, with more articles, code examples, and tutorials dedicated to it (and consequently JSON) than any other programming platform.

The web’s evolution has significantly contributed to JSON’s popularity. Stack Overflow reveals more questions about JSON than other data interchange formats.18

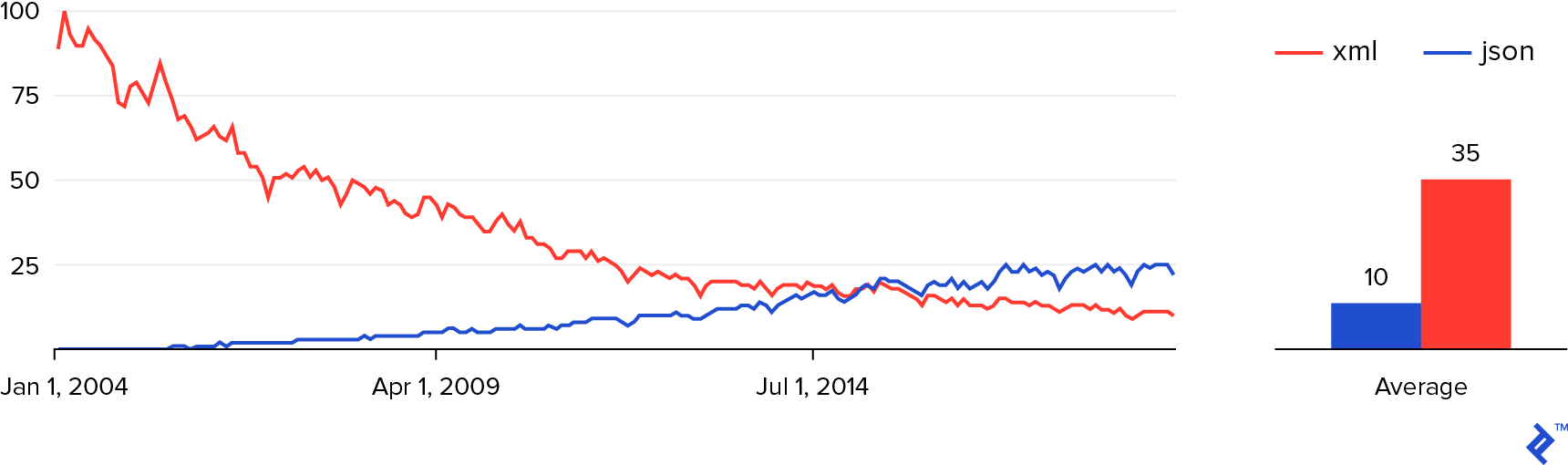

Google Trends reflects a similar trend when comparing search interest in JSON and XML.19

Does JavaScript’s dominance imply that JSON is inherently superior to XML?

Developer communities attribute JSON’s popularity to its concise syntax and straightforward semantics. Douglas Crockford highlights JSON’s advantages on JSON.org: “JSON is easier for humans and machines to understand due to its minimal syntax and predictable structure."20 Critics often point to XML’s verbosity as the “angle bracket tax."21 The requirement for closing tags in XML can lead to larger file sizes compared to JSON, especially when uncompressed. Moreover, many developers find XML less readable.22

JSON’s simplicity and concise nature have earned it praise, while XML’s perceived verbosity and complexity have led to its dismissal as outdated. However, many articles comparing the two offer a limited perspective, incorrectly portraying JSON as a direct replacement for XML.

The narrow focus of many articles has led to the misconception that XML is obsolete, neglecting its powerful features that contribute to robust software architecture, adaptability, and reduced software risk.

While JSON is a lightweight alternative to XML, its popularity stems from JavaScript’s dominance as the most widely used programming language. With JavaScript shaping software trends in recent years, JSON continues to garner more attention than any other data interchange format. The assertion that “JSON is better than XML” is common but often lacks proper justification beyond simplistic comparisons of syntax and verbosity. Determining whether one is inherently better requires a deeper evaluation of each standard.

In Conclusion

The web has undergone a significant transformation since 1990. The browser wars between Netscape and Microsoft led to HTML fragmentation, demanding a solution. XML emerged, formalizing XHTML and offering a powerful approach to computing. The evolution from server-rendered HTML pages to AJAX and SPAs shifted the focus to JavaScript, leading developers towards JSON.

JSON’s popularity is directly tied to JavaScript’s. JavaScript’s accessibility has attracted a wave of new software developers, and JSON, being natively integrated with this popular platform, naturally sees more questions on platforms like Stack Overflow than any other data interchange format.

As software trends draw more JavaScript developers, JSON has earned the title of “most popular data interchange format.”

While JSON may appear to be winning the “JSON vs. XML” debate, a closer look reveals a more complex reality.

Part 2 of this article will delve deeper into the technical strengths and weaknesses of JSON and XML. We’ll assess their suitability for various applications, including enterprise use cases. A deeper exploration of “data interchange” will uncover its impact on the overall software risk of applications. By understanding the fundamental differences between JSON and XML, developers can make informed decisions about which standard best suits their project’s requirements, ultimately building software that is more stable, less prone to bugs, and resilient to future changes.

As a side note, the JSON specification has a quirk: JavaScript objects with bidirectional relationships, where child properties reference parent properties, cannot be converted into JSON. Attempting to do so results in an Uncaught TypeError: Converting circular structure to JSON error. For a workaround, see Bidirectional Relationship Support in JSON.

References

1. The Internet: A Historical Encyclopedia. Chronology, Volume 3, p. 130 (ABC-CLIO, 2005) 2. Handbook Of Metadata, Semantics And Ontologies, p. 109 (World Scientific, December 2013) 3. World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) - History 4. “JavaSoft ships Java 1.0” (Sun Microsystems, January 1996) 5. Spatially Enabling the Next Generation Internet (David Engen, January 2002) 6. The story of XMLHTTP (AlexHopmann.com, January 2007) 7. Beginning Ajax - Page 2 (Wiley Publishing, March 2007) 8. Ajax: A New Approach to Web Applications (Jesse James Garrett, February 2005) 9. A Brief History of Ajax (Aaron Swartz, December 2005) 10. “What is Kayak.com?” (Corporate Backgrounder, October 2008) 11. Inner-Browsing: Extending the Browsing Navigation Paradigm (Netscape, May 2003) 12. “A self contained website using DHTML” (SlashDotSlash.com, July 2012) 13. Delivery of data and formatting information to allow client-side manipulation (US Patent Bureau, April 2002) 14. “What Is Ajax?” Professional Ajax, 2nd ed. (Wiley, March 2007) 15. Douglas Crockford: The JSON Saga (Yahoo!, July 2009) 16. ECMA Standard 404 (ECMA International, December 2017) 17. Ajax: A New Approach to Web Applications (Jesse James Garrett, February 2005) 18. Stack Overflow Trends (Stack Overflow, 2009-2019) 19. Google Trends (Google, 2004-2019) 20. JSON: The Fat-Free Alternative to XML (Crockford, 2006) 21. XML: The Angle Bracket Tax (Coding Horror, May 2008) 22. Xml Sucks (WikiWikiWeb, 2016)