Symfony2, a high-performance PHP framework, leverages the Dependency Injection Container (DIC) pattern. Components within this framework interact with the DIC through a dependency injection interface. This design promotes decoupling by allowing components to remain agnostic about their dependencies. During initialization, the ‘Kernel’ class instantiates the DIC and subsequently injects it into various components. However, this approach inadvertently opens the door for the DIC to be utilized as a Service Locator.

Symfony2 even provides the ‘ContainerAware’ class for this very purpose. While many consider the Service Locator an anti-pattern within the Symfony2 context, I beg to differ. It presents itself as a more straightforward pattern compared to DI, proving particularly beneficial in simpler projects. Nevertheless, the simultaneous employment of both the Service Locator and DIC patterns within a single project undeniably constitutes an anti-pattern.

This article endeavors to guide you through building a Symfony2 application devoid of the Service Locator pattern. We shall adhere to a fundamental principle: only the DIC builder is privy to the intricacies of the DIC.

Demystifying the DIC

In the realm of Dependency Injection, the DIC assumes the role of a dependency orchestrator, defining and managing service dependencies. Services, in turn, expose an injection interface, enabling the DIC to fulfill their dependencies. The subject of Dependency Injection has been extensively covered in numerous articles, which I trust you’ve had the opportunity to explore. Therefore, let’s dispense with theoretical elaborations and delve straight into the crux of the matter. DI can be broadly classified into three primary types:

Symfony simplifies the configuration of injection structures through intuitive configuration files. Here’s a glimpse into how these three injection types can be configured:

| |

Laying the Foundation: Project Bootstrapping

Let’s embark on structuring our base application. In tandem, we’ll seamlessly integrate the Symfony DIC component.

| |

To empower Composer’s autoloader to locate our custom classes residing within the ‘src’ folder, we can enhance the ‘composer.json’ file with an ‘autoloader’ property:

| |

Now, let’s bring our container builder to life while explicitly prohibiting container injections.

| |

In this instance, we leverage Symfony’s Config and Yaml components, the details of which can be found in the official documentation here. Furthermore, we establish a root path parameter, ‘app_root,’ for potential future use. The ‘get’ method overrides its counterpart in the parent class, modifying its default behavior to prevent the container from returning the “service_container.”

Our next order of business is to establish an entry point for our application.

| |

This entry point serves as the gatekeeper for HTTP requests. We retain the flexibility to introduce additional entry points tailored for console commands, cron tasks, and more. Each entry point is entrusted with the responsibility of retrieving specific services and must possess knowledge of the DIC structure. This constitutes the sole location where we can request services from the container. From this juncture onward, our mission is to construct the application exclusively through DIC configuration files.

HttpKernel: The Web Component Backbone

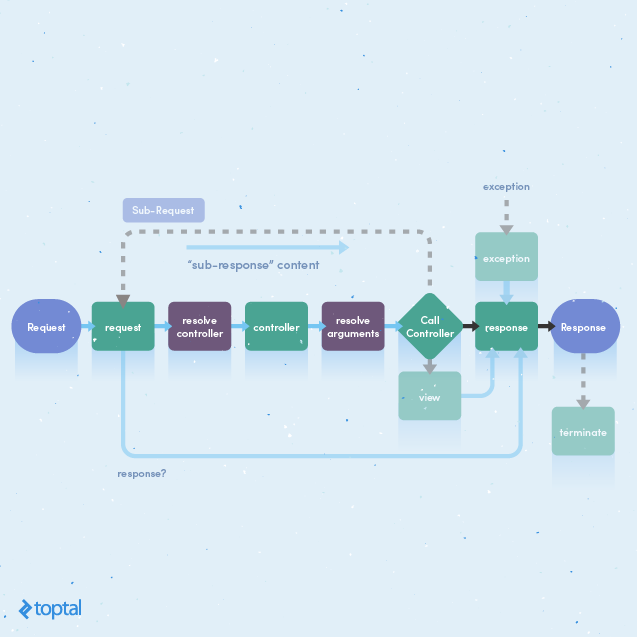

HttpKernel (distinct from the framework kernel that presents the service locator predicament) will serve as the foundational component for the web-facing aspect of our application. A typical HttpKernel workflow unfolds as follows:

Green squares symbolize events.

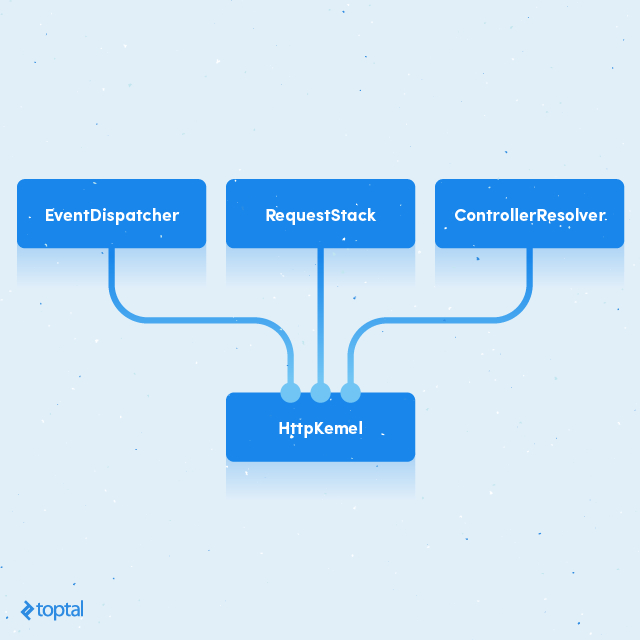

HttpKernel relies on the HttpFoundation component for Request and Response objects, and the EventDispatcher component for its event-driven architecture. Initializing these components through DIC configuration files poses no particular challenges. HttpKernel, however, mandates initialization with EventDispatcher, ControllerResolver, and optionally RequestStack (catering to sub-requests) services.

Here’s the corresponding container configuration:

| |

| |

| |

As you’ve likely observed, we employ the ‘factory’ property to instantiate the request service. The HttpKernel service receives a Request object as input and produces a Response object as output. This exchange can be neatly encapsulated within the front controller.

| |

Alternatively, the response can be defined as a service within the configuration, again utilizing the ‘factory’ property.

| |

Subsequently, we can effortlessly retrieve it within the front controller.

| |

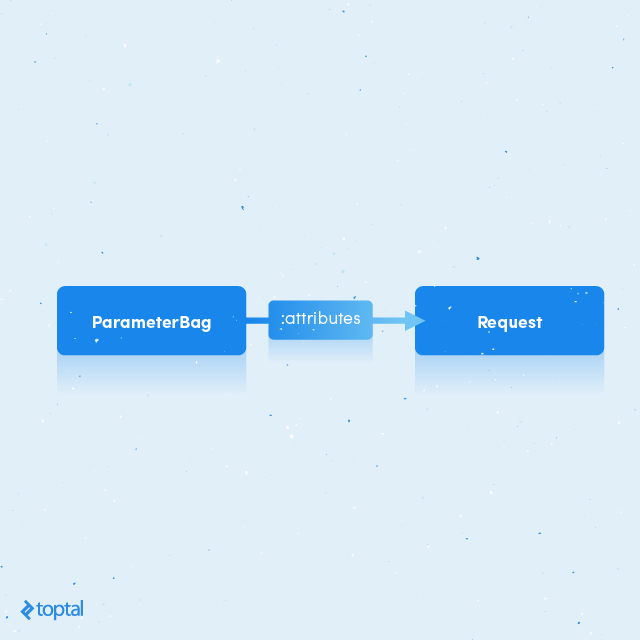

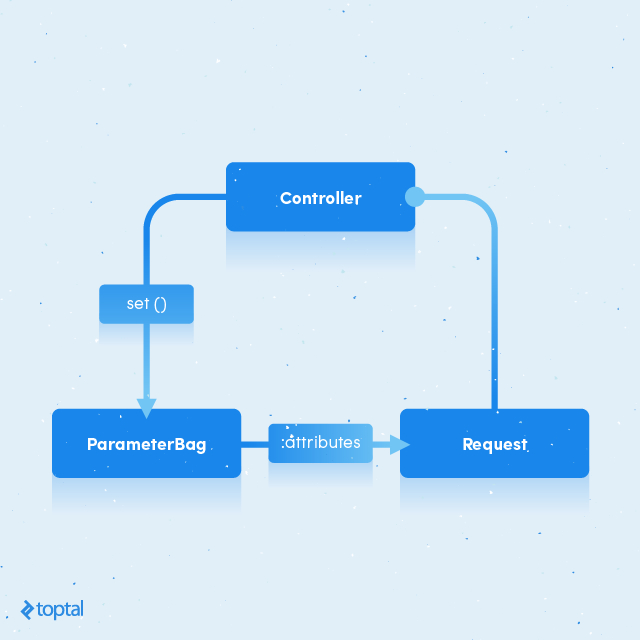

The controller resolver service extracts the ‘_controller’ property from the attributes of the Request service to pinpoint the appropriate controller. While these attributes can be defined within the container configuration, the process is slightly more intricate due to the requirement of using a ParameterBag object in lieu of a simple array.

| |

Here’s the DefaultController class, complete with its defaultAction method.

| |

With these pieces in place, we should now have a functional application.

Admittedly, this controller is rather rudimentary as it lacks access to any services. The Symfony framework addresses this by injecting the DIC into controllers, enabling their use as service locators. However, we’re striving for a different approach. Therefore, let’s define the controller as a service and inject the request service into it. Here’s the configuration:

| |

| |

| |

And the accompanying controller code:

| |

Now, our controller enjoys access to the request service. You’ll notice that this scheme introduces circular dependencies. This functions seamlessly due to the DIC’s behavior of sharing services after creation but before method and property injections. Consequently, when the controller service is being created, the request service is already available.

Here’s a visual representation of the process:

However, this arrangement hinges on the request service being created first. When we fetch the response service within the front controller, the request service is the initial dependency initialized. Attempting to retrieve the controller service first would trigger a circular dependency error. This can be rectified using method or property injections.

Yet, another challenge awaits. The DIC will initialize every controller along with its dependencies. This implies that all existing services will be initialized, even if they are not required. Fortunately, the container offers lazy loading capabilities. The Symfony DI-component leverages ‘ocramius/proxy-manager’ to generate proxy classes. We need to establish a bridge between them.

| |

And include it during the container building phase:

| |

Now, we can define services with lazy loading behavior.

| |

With this in place, controllers will only trigger the initialization of their dependent services when a method is actually invoked. Moreover, it circumvents circular dependency errors because the controller service will be shared before its actual initialization. Nonetheless, we must remain vigilant about avoiding circular references. In this scenario, we should refrain from injecting the controller service into the request service or vice versa. Since we inherently require the request service within controllers, let’s prevent injection into the request service during the container initialization phase. HttpKernel’s event system comes to our rescue.

Routing: Directing Traffic

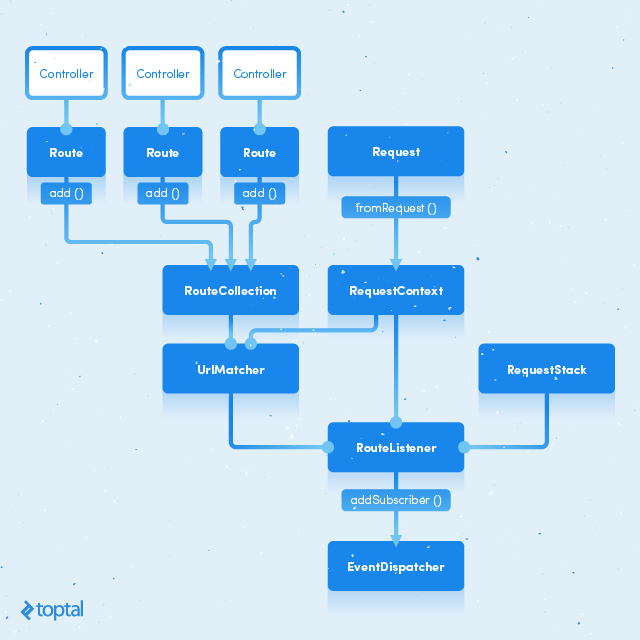

Naturally, we desire distinct controllers to handle different requests. Enter the routing system. Let’s incorporate the Symfony routing component.

| |

The routing component features the Router class, which can interpret routing configuration files. However, these configurations are essentially key-value pairs tailored for the Route class. The Symfony framework employs its own controller resolver from the FrameworkBundle, which injects the container into controllers using the ‘ContainerAware’ interface—precisely what we’re aiming to avoid. HttpKernel’s controller resolver returns a class object as is if it’s already present in the ‘_controller’ attribute as an array containing the controller object and the action method as a string (in reality, the controller resolver will return anything that is an array). Therefore, we must define each route as a service and inject the corresponding controller into it. Let’s introduce another controller service to illustrate this concept.

| |

| |

The HttpKernel component provides the RouteListener class, which hooks into the ‘kernel.request’ event. Here’s a potential configuration utilizing lazy controllers:

| |

| |

| |

| |

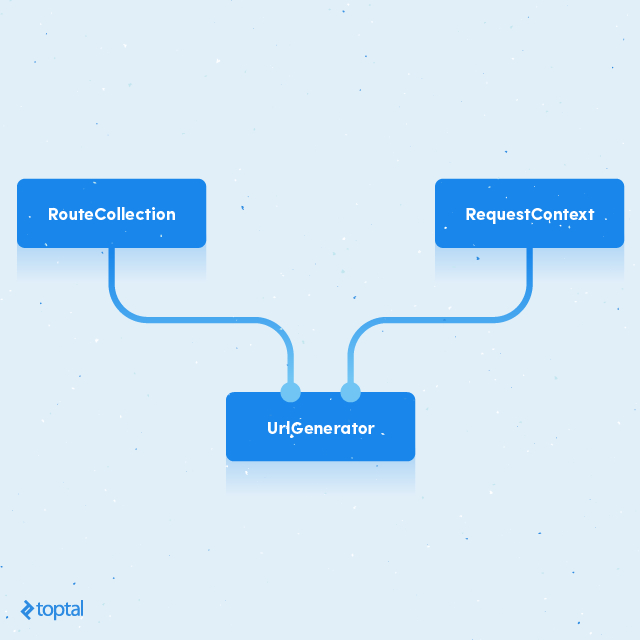

Furthermore, our application necessitates a URL generator. Here’s the implementation:

| |

The URL generator can be injected into controllers and rendering services. With that, we’ve established the foundation of our application. Any additional service can be defined following the same pattern, with the configuration file injected into the relevant controllers or event dispatcher. For instance, let’s examine configurations for Twig and Doctrine.

Twig: The Templating Powerhouse

Twig reigns supreme as the default template engine in the Symfony2 framework. Numerous Symfony2 components seamlessly integrate with Twig without requiring adapters, making it a natural choice for our application.

| |

| |

Doctrine: The ORM of Choice

Doctrine stands as a prominent ORM within the Symfony2 ecosystem. While we retain the flexibility to opt for alternative ORMs, Symfony2 components are already equipped to leverage various Doctrine features.

| |

| |

| |

As an alternative to annotations, we can embrace YML and XML mapping configuration files. This simply entails utilizing the ‘createYAMLMetadataConfiguration’ and ‘createXMLMetadataConfiguration’ methods and specifying the path to the directory housing these configuration files.

Individually injecting every required service into each controller can quickly become tedious. To alleviate this, the DIC component offers abstract services and service inheritance. This enables us to define abstract controllers:

| |

| |

Symfony boasts an array of other valuable components, including Form, Command, and Assets. Developed as independent components, their integration using the DIC should pose no significant hurdles.

Tags: Enhancing Organization and Flexibility

The DIC incorporates a tagging system. Tags can be processed by Compiler Pass classes. While the Event Dispatcher component includes its own Compiler Pass to streamline event listener subscription, it relies on the ContainerAwareEventDispatcher class instead of the standard EventDispatcher class, rendering it unsuitable for our purposes. However, we can implement our own compiler passes for events, routing, security, and other functionalities.

As an illustration, let’s implement tags for the routing system. Currently, defining a route entails defining a route service in a route configuration file within the ‘config/routes’ directory and then adding it to the route collection service within the ‘config/routing.yml’ file. This approach feels disjointed, as we define router parameters and the router name in separate locations.

By introducing a tag system, we can simply specify a route name within a tag and add this route service to the route collection using the tag name.

The DIC component leverages compiler pass classes to modify container configurations before initialization. Let’s create our own compiler pass class for the router tag system.

| |

| |

Now, let’s refactor our configuration:

| |

| |

As you can see, we now retrieve route collections using the tag name rather than the service name. This decoupling ensures that our route tag system operates independently of the specific configuration. Moreover, routes can be added to any collection service equipped with an ‘add’ method. Compiler passers can significantly streamline dependency configurations. However, it’s crucial to exercise caution, as they can introduce unexpected behavior into the DIC. It’s advisable to avoid modifying existing logic, such as altering arguments, method calls, or class names. Instead, focus on adding new functionality on top of the existing structure, as we’ve done with tags.

Conclusion: Embracing the DIC Pattern

We now have an application that adheres strictly to the DIC pattern, constructed entirely using DIC configuration files. As we’ve demonstrated, building a Symfony application in this manner doesn’t present any insurmountable obstacles. This approach also provides a clear and visual representation of your application’s dependencies. The primary reason developers often resort to using the DIC as a service locator stems from the relative ease of understanding the service locator concept. Consequently, vast codebases riddled with DICs masquerading as service locators are often a testament to this tendency.

The source code for this application can be found on GitHub.