Apache Lucene is a Java framework designed for full-text search capabilities. It forms the backbone of renowned search servers like Solr and Elasticsearch. Beyond dedicated search platforms, it seamlessly integrates into Java-based applications, ranging from Android apps to robust web backends.

While Lucene boasts an extensive array of configuration options, catering primarily to database developers handling generic text corpora, leveraging the inherent structure or specific content types of your documents can significantly enhance both search precision and query versatility.

To illustrate this customization potential, this Lucene tutorial will guide you through indexing the vast collection of Project Gutenberg, a repository housing thousands of public domain e-books. Given the prevalence of novels within this corpus, let’s assume a particular interest in extracting and analyzing the dialogue present within these narratives. However, neither Lucene, Elasticsearch, nor Solr natively support dialogue identification. In fact, their standard text analysis discards punctuation during the initial processing stages, hindering our ability to isolate dialogue segments. Consequently, it’s within these early stages that our customization journey begins.

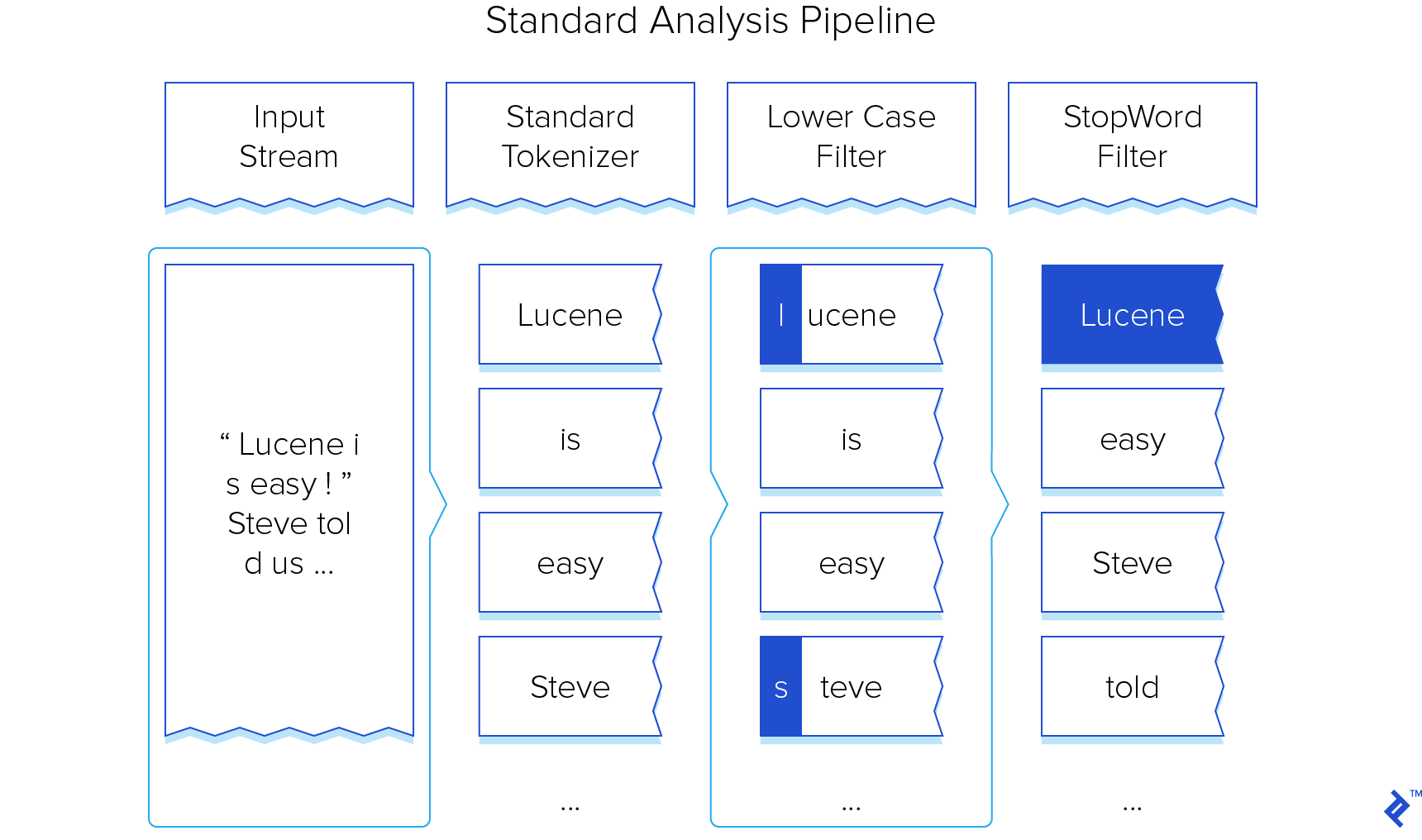

Deconstructing the Apache Lucene Analysis Pipeline

The Lucene analysis JavaDoc offers a comprehensive overview of the intricate workings within the text analysis pipeline.

In essence, envision the analysis pipeline as a process that ingests a raw stream of characters and transforms them into “terms” - analogous to words - at the output.

The typical analysis pipeline can be visualized as follows:

Our exploration will focus on customizing this pipeline to effectively recognize and demarcate regions of text enclosed within double quotes, which we’ll denote as dialogue. Subsequently, we’ll enhance the ranking of matches occurring within these identified dialogue segments.

Character Input and Handling

During the initial document indexing phase, characters are read from a Java InputStream, enabling diverse input sources such as files, databases, or even web service calls. For our Project Gutenberg index, we’ll download the e-books and employ a simple application to read these files, subsequently writing their content to the index. As both Lucene index creation and file reading are well-established processes, we’ll gloss over their intricacies. The fundamental code snippet for index generation is provided below:

| |

Observe how each e-book maps to a single Lucene Document, implying that our future search results will comprise a list of matching books. Setting Store.YES for the title field ensures that the filename is stored. Conversely, we opt not to store the entire e-book body to conserve disk space, as it’s redundant for our search requirements.

The actual character stream reading commences with the addDocument call. The IndexWriter pulls tokens from the pipeline’s terminus, propagating this pull back through the pipeline until it reaches the initial stage, the Tokenizer, which reads directly from the InputStream.

Noteworthy is that we don’t explicitly close the stream, as Lucene gracefully handles this behind the scenes.

Character Tokenization

The default Lucene StandardTokenizer disregards punctuation, necessitating our intervention at this stage, as preserving quotes is paramount for our objective.

While the StandardTokenizer documentation suggests copying and tailoring its source code, this approach would introduce unnecessary complexity. Instead, we’ll leverage the flexibility of CharTokenizer, which allows us to define characters to “accept,” treating all others as delimiters between tokens and discarding them accordingly. Given our focus on words and their enclosing quotations, our custom Tokenizer takes the following concise form:

| |

When presented with an input stream like [He said, "Good day".], this tokenizer would generate the following tokens: [He], [said], ["Good], [day"].

Notice how the quotes are embedded within the resulting tokens. While it’s technically feasible to construct a Tokenizer that isolates quotes as individual tokens, this approach entangles us in intricate buffering and scanning mechanisms best left to the robust internals of the Tokenizer. Instead, we’ll strive for a clean Tokenizer and delegate the refinement of the token stream to later stages in the pipeline.

Token Refinement using Filters

Following the tokenizer, a series of TokenFilter objects comes into play. Note that the term “filter” might be slightly misleading, as a TokenFilter possesses the capability to add, remove, or modify tokens.

Many of Lucene’s built-in filter classes anticipate individual words as input, rendering our current stream of word-and-quote tokens incompatible. Consequently, our Lucene tutorial’s next customization step involves introducing a filter to sanitize the output generated by our QuotationTokenizer.

This cleanup operation entails generating an additional start quote token if a quote appears at the beginning of a word or an end quote token if it’s located at the end. For simplicity, we’ll disregard the handling of single-quoted words.

Creating a TokenFilter subclass boils down to implementing a single method: incrementToken. This method is responsible for invoking incrementToken on the preceding filter in the pipeline and subsequently manipulating the returned results to achieve the desired filter behavior. The results of incrementToken are accessed through Attribute objects, representing the current state of token processing. Upon the completion of our incrementToken implementation, these attributes should reflect the modifications necessary to prepare the token for the next filter in line or for indexing if we’ve reached the pipeline’s end.

The attributes pertinent to our current stage in the pipeline are:

CharTermAttribute: This attribute houses achar[]buffer storing the current token’s characters, which we’ll manipulate to either remove the quote or create a dedicated quote token.TypeAttribute: This attribute encapsulates the current token’s “type.” Since we’re augmenting the token stream with start and end quotes, our filter will introduce two novel types.OffsetAttribute: Optionally, Lucene can store references to the original document locations of terms, termed “offsets.” These offsets are essentially start and end indices within the initial character stream. If we modify theCharTermAttributebuffer to point to a mere substring of the original token, we must adjust these offsets accordingly.

You might be curious about the rationale behind the convoluted API for manipulating token streams, particularly why we can’t simply employ something like String#split on the incoming tokens. The answer lies in Lucene’s optimization for high-speed, low-overhead indexing, enabling its built-in tokenizers and filters to rapidly process gigabytes of text while maintaining a minimal memory footprint. This efficiency stems from minimizing allocations during tokenization and filtering, with Attribute instances intended for single allocation and reuse. Adhering to this paradigm when designing your tokenizers and filters, while also minimizing allocations, allows you to customize Lucene without compromising its performance.

With these considerations in mind, let’s delve into the implementation of a filter capable of transforming a token like ["Hello] into two distinct tokens, ["] and [Hello]:

| |

We initiate the process by obtaining references to the aforementioned attributes, appending “Attr” to the field names for clarity in subsequent references. It’s plausible that certain Tokenizer implementations might not furnish these attributes, prompting us to utilize addAttribute to acquire our references. If absent, addAttribute will instantiate an attribute instance; otherwise, it’ll procure a shared reference to the attribute of the corresponding type. Note that Lucene prohibits the simultaneous existence of multiple instances of the same attribute type.

| |

Given that our filter introduces a new token absent in the original stream, we require a mechanism to persist the state of this token between consecutive calls to incrementToken. Since we’re essentially splitting an existing token into two, it’s sufficient to track solely the offsets and type of the newly generated token. Additionally, we maintain a flag signaling whether the next invocation of incrementToken should emit this extra token. While Lucene offers captureState and restoreState methods for this purpose, these entail allocating a State object, potentially introducing more complexity than manual state management, so we’ll opt for the latter approach.

| |

In line with its aggressive allocation avoidance, Lucene can reuse filter instances. In such scenarios, a call to reset is expected to revert the filter to its initial state. Thus, we simply reset our extra token fields.

| |

Here’s where the core logic resides. When our incrementToken implementation is invoked, we have the option to not propagate the incrementToken call to the preceding stage in the pipeline. By doing so, we effectively introduce a new token, as we’re not pulling one from the Tokenizer.

Instead, we invoke advanceToExtraToken to configure the attributes for our extra token, set emitExtraToken to false to prevent re-entering this branch on the next call, and return true, signaling the availability of another token.

| |

The remainder of the incrementToken logic handles one of three scenarios. Recall that termBufferAttr allows us to inspect the content of the token traversing the pipeline:

If we’ve reached the end of the token stream (indicated by

hasNextbeing false), our task is complete, and we simply return.If we encounter a token comprising more than one character, with one of those characters being a quote, we proceed to split the token.

If the token consists of a solitary quote, we assume it to be an end quote. This assumption stems from the fact that starting quotes invariably precede a word (without any intervening punctuation), whereas ending quotes can follow punctuation (as in the sentence,

[He told us to "go back the way we came."]). In such cases, the ending quote will already be an independent token, requiring only a type adjustment.

The methods splitTermQuoteFirst and splitTermWordFirst are responsible for configuring the attributes to represent the current token as either a word or a quote, simultaneously setting up the “extra” fields to allow consumption of the other half later. Due to their similarity, we’ll focus on splitTermQuoteFirst:

| |

To split the token with the quote appearing first in the stream, we truncate the buffer by setting its length to one (representing the single quote character). We adjust the offsets accordingly (pointing to the quote’s location in the original document) and set the type to indicate a starting quote.

The prepareExtraTerm method handles setting the extra* fields and toggling emitExtraToken to true. It’s invoked with offsets pointing to the “extra” token (i.e., the word following the quote).

The complete source code for QuotationTokenFilter can be found in available on GitHub.

As a side note, while this particular filter generates only a single extra token, this approach can be extended to introduce an arbitrary number of extra tokens. This involves replacing the extra* fields with a collection or, more efficiently, a fixed-length array if there’s a constraint on the number of generatable extra tokens. Refer to SynonymFilter and its PendingInput inner class for a practical illustration of this concept.

Quote Token Consumption and Dialogue Marking

Having invested effort in injecting these quotes into the token stream, we can now leverage them to delineate dialogue sections within the text.

Since our ultimate goal is to tailor search results based on whether terms are part of dialogue, we need to associate metadata with these terms. Lucene provides the PayloadAttribute for this purpose. Payloads, essentially byte arrays stored alongside terms in the index, can be retrieved during subsequent searches. It’s worth noting that our current flag implementation, occupying an entire byte, is somewhat wasteful. In a real-world scenario, additional payloads could be implemented as bit flags to optimize storage efficiency.

Below is a new filter, DialoguePayloadTokenFilter, positioned at the very end of our analysis pipeline. Its purpose is to attach a payload indicating whether a token belongs to a dialogue section.

| |

This filter, requiring only a single state variable (withinDialogue), is considerably simpler. A start quote signifies our entry into a dialogue section, while an end quote marks its conclusion. In both cases, the quote token itself is discarded by making a subsequent call to incrementToken, effectively ensuring that neither start quote nor end quote tokens propagate beyond this stage.

For instance, DialoguePayloadTokenFilter would transform the following token stream:

| |

into the following:

| |

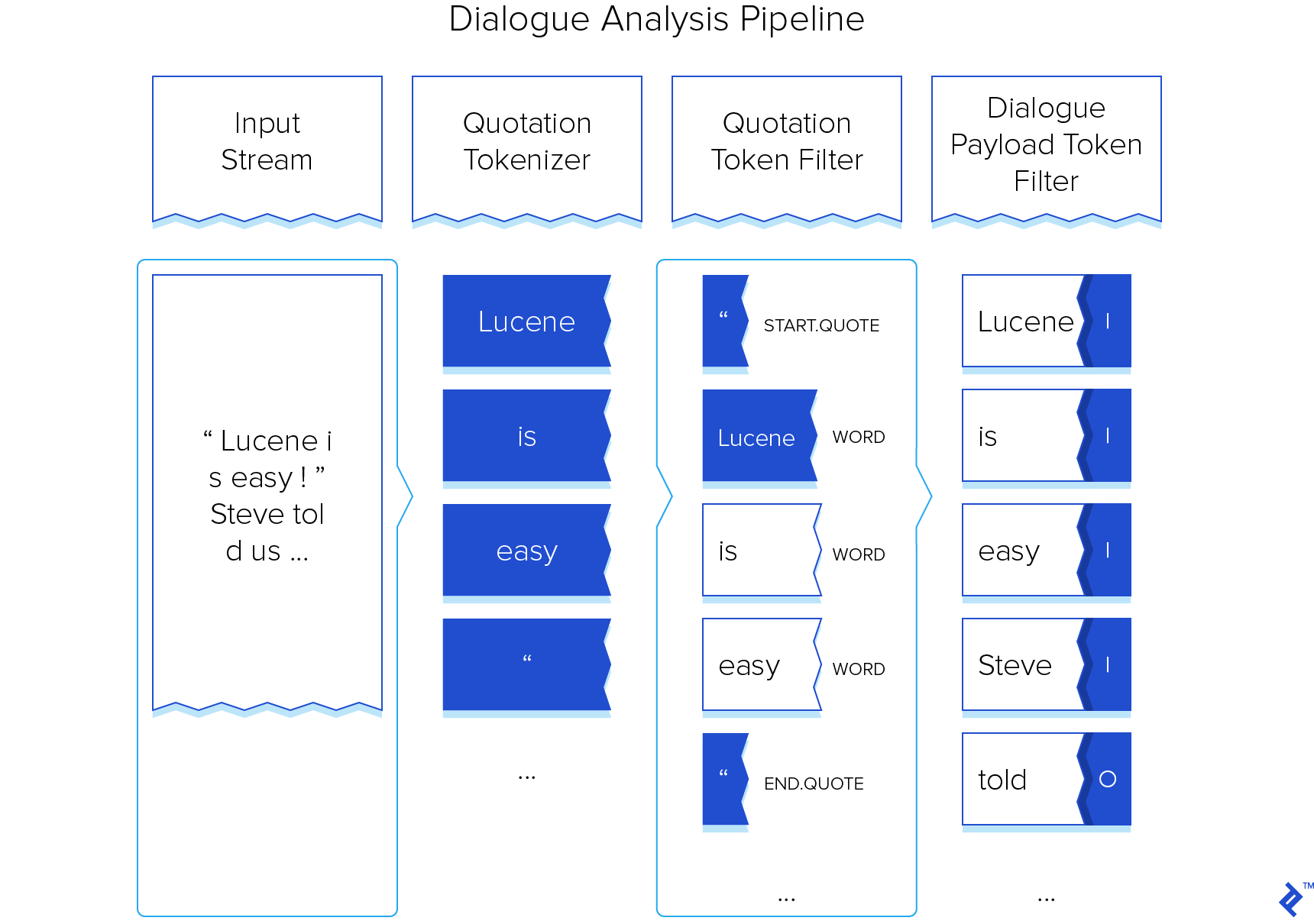

Assembling Tokenizers and Filters into an Analyzer

The Analyzer component assumes the responsibility of assembling the analysis pipeline, typically by combining a Tokenizer with a sequence of TokenFilters. Additionally, Analyzers can define how this pipeline is reused across multiple analyses. However, this aspect is irrelevant for our use case, as our components solely require a call to reset() between uses, which Lucene handles automatically. Our task boils down to assembling the pipeline by implementing the Analyzer#createComponents(String) method:

| |

Recall that filters maintain a backward reference to the preceding stage in the pipeline, guiding our instantiation process. We also integrate two filters from the StandardAnalyzer: LowerCaseFilter and StopFilter. These must follow the QuotationTokenFilter to ensure that any quote separation has already taken place. We have more flexibility in positioning the DialoguePayloadTokenFilter, as any position after QuotationTokenFilter suffices. Our choice to place it after StopFilter stems from the desire to avoid wasting time injecting the dialogue payload into stop words, which will ultimately be removed.

Here’s a visualization of our modified pipeline in action (excluding parts of the standard pipeline already covered or removed):

With our custom DialogueAnalyzer ready, it can now be employed like any other stock Analyzer, allowing us to proceed with index construction and, subsequently, search functionality.

Full-Text Search within Dialogue

Had our objective been solely searching within dialogue, we could have simply discarded all non-quoted tokens and called it a day. However, by preserving the entirety of the original tokens, we’ve retained the flexibility to either incorporate dialogue awareness into our queries or treat dialogue on par with any other textual element.

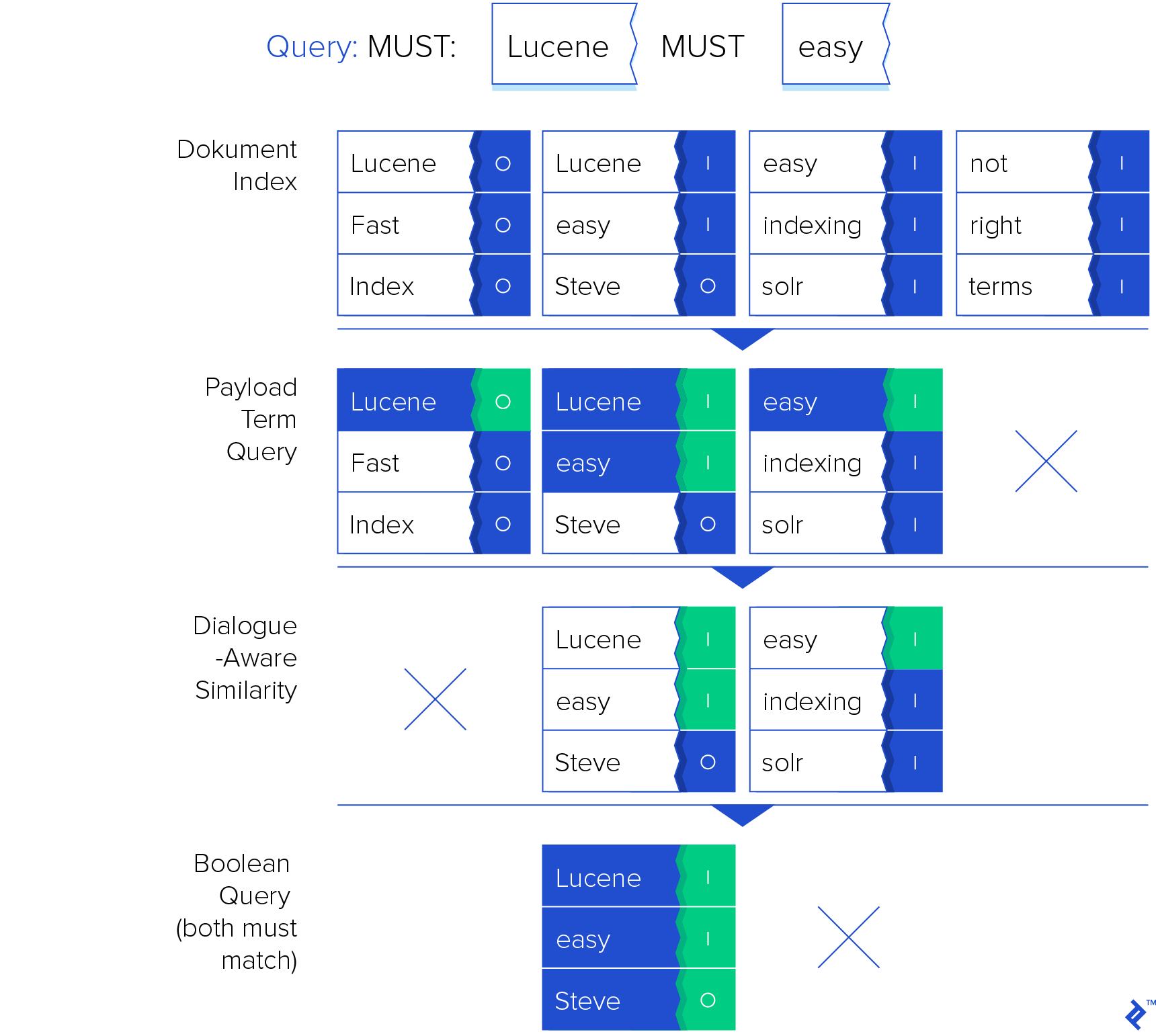

The fundamentals of querying a Lucene index are well-documented. For our purposes, it suffices to understand that queries consist of Term objects linked together by operators like MUST or SHOULD, used to identify matching documents based on these terms. The matching documents are then scored using a configurable Similarity object, allowing for result ordering, filtering, or limiting based on this score. For instance, Lucene allows us to retrieve the top ten documents containing both the terms [hello] and [world].

Customizing search results based on dialogue presence can be achieved by modulating a document’s score based on its payload. The initial extension point for this customization lies within the Similarity component, responsible for term weighting and overall scoring.

Customizing Similarity and Scoring

By default, queries employ the DefaultSimilarity implementation, which assigns term weights based on their frequency within a document. This component presents an ideal extension point for fine-tuning weights, prompting us to extend it to incorporate payload-based document scoring. The DefaultSimilarity#scorePayload method is specifically provided for this purpose:

| |

Our custom DialogueAwareSimilarity assigns a score of zero to payloads not belonging to dialogue. Since each Term can have multiple matches, potentially resulting in multiple payload scores, the interpretation of these scores is delegated to the Query implementation.

Pay close attention to the BytesRef holding the payload: we must specifically check the byte at the specified offset, as we can’t guarantee that the byte array represents the same payload we stored earlier. When reading the index, Lucene prioritizes memory efficiency and avoids allocating separate byte arrays solely for the scorePayload call, providing us with a reference to an existing byte array instead. This highlights the importance of prioritizing performance over developer convenience when working with the Lucene API.

With our new Similarity implementation in place, we need to configure the IndexSearcher responsible for executing queries to use it:

| |

Payload-Aware Queries and Terms

Now that our IndexSearcher is equipped with payload scoring capabilities, we need to construct a payload-aware query. The PayloadTermQuery serves this purpose, enabling us to match a single Term while also taking into account the payloads associated with those matches:

| |

This query specifically targets the term [hello] within the body field (where we stored our document content). Additionally, we provide a function to compute the final payload score from all term matches, plugging in the AveragePayloadFunction to average all individual payload scores. For example, if the term [hello] appears twice within dialogue and once outside, the final payload score would be ²⁄₃. This final score is then multiplied by the document’s overall score provided by DefaultSimilarity.

Our choice of averaging stems from the desire to downplay search results where a significant portion of the matched terms occur outside dialogue, effectively assigning a score of zero to documents devoid of any in-dialogue term occurrences.

Furthermore, we can combine multiple PayloadTermQuery objects using a BooleanQuery if our search criteria involve multiple terms within dialogue. Note that term order is irrelevant for this particular query type, though other query types are position-sensitive:

| |

Executing this query showcases the interplay between our custom query structure and the similarity implementation:

Query Execution and Explanation

To execute the constructed query, we hand it off to the IndexSearcher:

| |

Collector objects are used to manage the collection of matching documents. These collectors can be composed to achieve various combinations of sorting, limiting, and filtering. For instance, to retrieve the top ten scoring documents containing at least one term within dialogue, we can combine the TopScoreDocCollector and PositiveScoresOnlyCollector. By enforcing positive scores only, we ensure that zero-score matches (documents lacking any in-dialogue terms) are effectively filtered out.

To observe this query in action, we can execute it and then employ the IndexSearcher#explain method to gain insights into the scoring of individual documents:

| |

In this code snippet, we iterate over the document IDs present in the TopDocs instance obtained from the search. We also utilize the IndexSearcher#doc method to retrieve the title field for display purposes. For our sample query "hello", the output would resemble:

| |

Despite the jargon-laden output, we can discern how our custom Similarity implementation factored into the scoring process and how the MaxPayloadFunction yielded a multiplier of 1.0 for these particular matches. This implies that the payload was successfully loaded and scored, with all occurrences of "Hello" residing within dialogue sections, propelling these results to the top of the list as anticipated.

It’s worth noting that our Project Gutenberg index, with payloads included, occupies nearly four gigabytes of storage. Remarkably, even on a modest development machine, queries execute instantaneously, highlighting that our search customization hasn’t come at the expense of performance.

Conclusion

Lucene is a powerful, purpose-built full-text search library adept at transforming raw character streams into indexed terms, facilitating rapid index querying and ranked result retrieval. It offers ample extension points without compromising efficiency, allowing for sophisticated customization.

By integrating Lucene directly into our applications or utilizing it as part of a dedicated search server, we unlock the capability to perform real-time full-text searches across vast amounts of data. Moreover, through custom analysis and scoring, we can exploit domain-specific document features to elevate result relevance and construct highly specialized queries.

Complete code listings accompanying this Lucene tutorial can be found available on GitHub. The repository comprises two applications: LuceneIndexerApp for index construction and LuceneQueryApp for query execution.

The Project Gutenberg corpus, readily available as a BitTorrent download, provides a wealth of reading material to explore, both with Lucene and through traditional means.

Happy indexing!