I love to travel, and Couchsurfing is a favorite of mine. It’s a worldwide network of travelers where you can find lodging or offer your place to others. More than that, Couchsurfing connects you with locals, making for a more authentic travel experience. I’ve been part of the Couchsurfing community for over three years, starting with meetups and eventually hosting people. What an incredible journey! I’ve connected with amazing individuals from around the globe, forming many friendships. This experience has truly been life-changing.

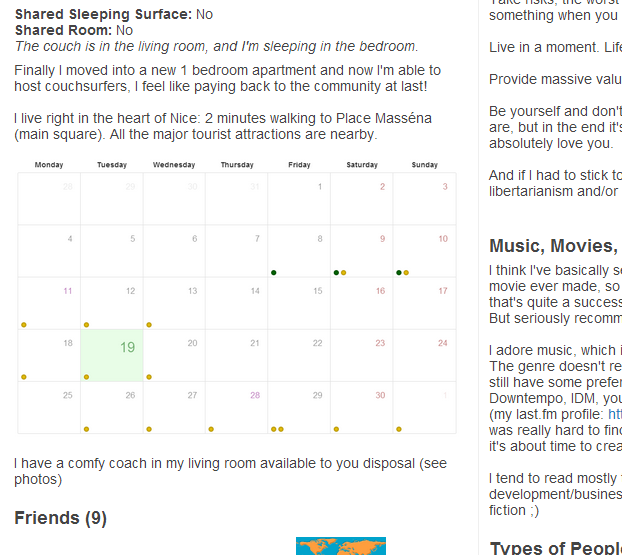

Personally, I’ve hosted many more travelers than I’ve surfed with. Living in a popular tourist spot on the French Riviera, I received tons of couch requests (up to ten daily during peak season). As a freelance back-end developer, I quickly realized that couchsurfing.com struggles to handle such high demand. The site lacks information about couch availability - when you get a request, you can’t be sure if you’re already hosting someone. A visual representation of accepted and pending requests would greatly improve management. Additionally, making couch availability public could prevent unnecessary requests. Consider Airbnb’s calendar for a good example.

Many companies are infamous for ignoring their users. Knowing Couchsurfing’s past, I didn’t expect them to implement this feature soon. The community has declined since the platform went commercial. To understand why, I recommend these articles:

- http://www.nithincoca.com/2013/03/27/the-rise-and-fall-of-couchsurfing/

- http://mechanicalbrain.wordpress.com/2013/03/04/couchsurfing-a-sad-end-to-a-great-idea/

I knew this functionality would be welcomed by many community members. So, I built an app to address this. However, there’s no public Couchsurfing API. Here’s the response I received from their support:

“Unfortunately we have to inform you that our API is not actually public and there are no plans at the moment to make it public.”

Accessing My Couch

It was time to employ my reverse engineering skills to crack Couchsurfing.com. I figured their mobile apps must use an API to communicate with the backend. So, I set up a local network proxy and connected my iPhone to intercept HTTP requests. This helped me identify access points for their private API and decipher their JSON payload format.

Finally, I built a website to help users manage couch requests and display couch availability calendars. I shared a link on their community forums (which are quite fragmented, making it hard to find information). The response was mostly positive, though some disliked that the site required couchsurfing.com credentials, raising trust concerns.

The website worked like this: log in with your couchsurfing.com credentials, and with a few clicks, get the HTML code to embed into your profile. Voila - an automatically updated calendar on your profile. Below is a screenshot of the calendar. Here are articles on how I built it:

Having created a valuable feature for Couchsurfing, I assumed they’d appreciate it - maybe even offer me a developer position. I emailed jobs(at)couchsurfing.com with the website link, my resume, and a reference. One of my guests had left this thank-you note:

Days later, they addressed my reverse engineering. Their reply focused solely on their security, asking me to remove the blog posts about the API and eventually the website. I removed the posts immediately, as my goal wasn’t to violate their terms or steal credentials but to help the community. I felt treated like a criminal, with the company fixated on the website requiring user credentials.

I offered them my app for free, suggesting they host it and integrate Facebook authentication. After all, the community needed this great feature. Here’s their final response:

“We are getting back into the swing of things here after the holidays and wanted to follow up.

We have had some internal discussion about your application and how we could both honor the creativity and initiative it shows while not potentially compromising the privacy and security of Couchsurfing users’ data when they enter their credentials into a third-party site.

The calendar clearly fills a feature hole on our site, a feature that is part of a larger project that we are working on now.

But the issue of collecting usernames and passwords remains. We couldn’t come up with an easy way to set it up so that we could host or support that on our side without either allowing you to access that data or have your site be seen as our work product.

The API that is currently available is soon to be replaced with a version that will require authentication/authorization from applications that access it.”

As I write this reverse engineering tutorial (a year later), Couchsurfing still lacks a calendar feature.

Back to Basics - Hacking My Couch, Again

A few weeks ago, I was inspired to write about reverse engineering private APIs. Naturally, I wanted to summarize my previous articles on the topic and add more detail. As I started, I aimed to demonstrate the process with an up-to-date API and try another round of API hacking. Based on my past experience and Couchsurfing’s recent launch of a brand new website and mobile app http://blog.couchsurfing.com/the-future-of-couchsurfing-is-on-the-way/, I decided to hack their API again.

Why reverse engineer? Firstly, it’s fun! It challenges both your technical skills and intuition. Educated guesses can save you significant time compared to brute-force methods. I recently heard about a company struggling to decode an undocumented API response. After days, someone tried adding ?decode=true to the URL and got valid JSON. Sometimes, prettifying the JSON response is all it takes.

Secondly, I’m impatient. Some companies take ages to implement user-requested features. Instead of waiting, you can leverage their private API and build it yourself.

So, I tackled the new couchsurfing.com API, beginning with a familiar approach: installing their latest iOS app.

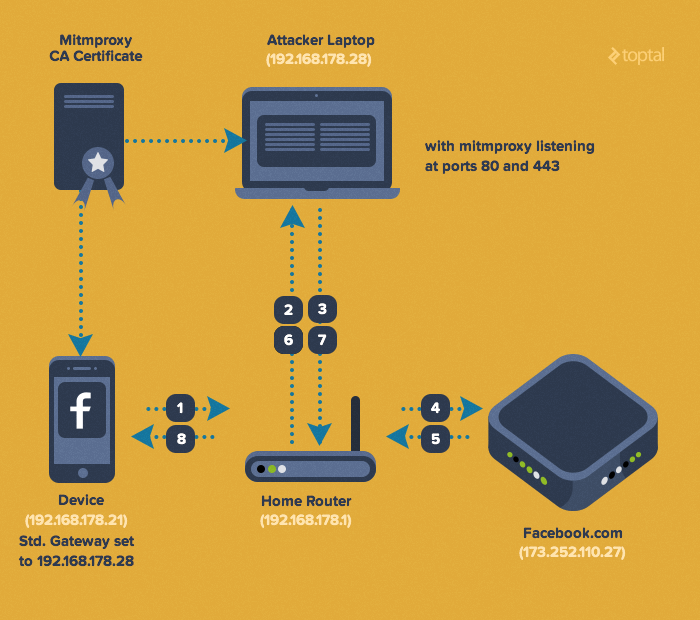

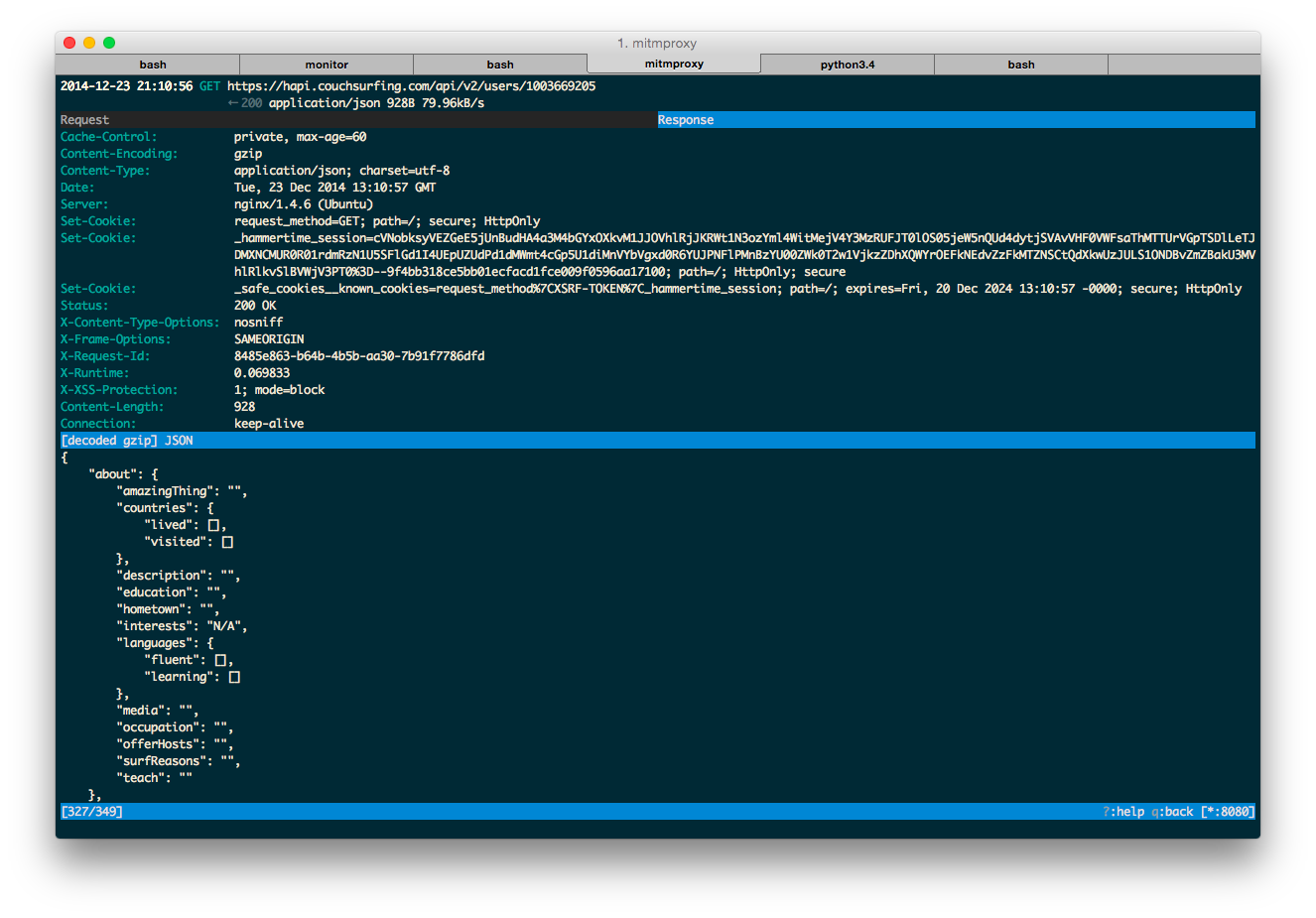

First, you establish a LAN proxy to intercept app-to-API HTTP requests using a man-in-the-middle attack (MITM).

For unencrypted connections, this is straightforward - the client connects to the proxy, which relays requests to the server. You can even modify the payload if needed. On public Wi-Fi, impersonating the router makes this quite simple.

Encrypted connections are slightly different: requests are encrypted end-to-end, preventing attackers from decrypting them without the private key (which is never transmitted). However, while the API communication is secure, the endpoints, especially the client, aren’t as safe.

SSL requires these conditions:

- The server’s certificate must be signed by a trusted Certificate Authority (CA)

- The server’s common name in the certificate must match its domain name

To bypass encryption in a MITM attack, the proxy acts as a CA, generating certificates on-the-fly. For example, if a client connects to www.google.com, the proxy creates and signs a certificate for that domain, making the client believe it’s communicating directly with Google.

For our sniffing proxy, I’ll use mitmproxy. Any transparent HTTPS proxy works. Charles is another option with a nice GUI. Here’s the setup:

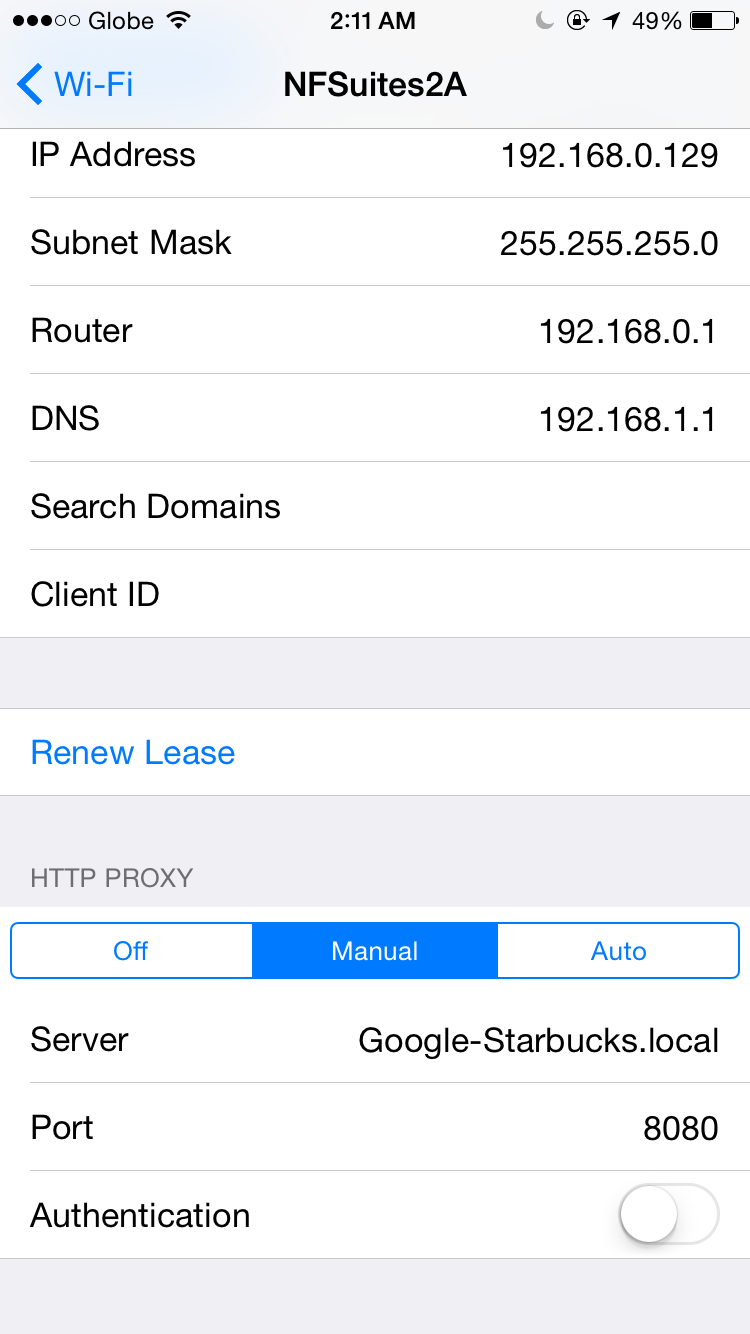

- Configure your phone’s Wi-Fi gateway as the proxy, ensuring all packets pass through it.

- Install the proxy’s certificate on your phone, adding its public key to the trusted store.

Consult your proxy’s documentation for certificate installation. Here provides instructions for mitmproxy, and here is the certificate PEM file for iOS.

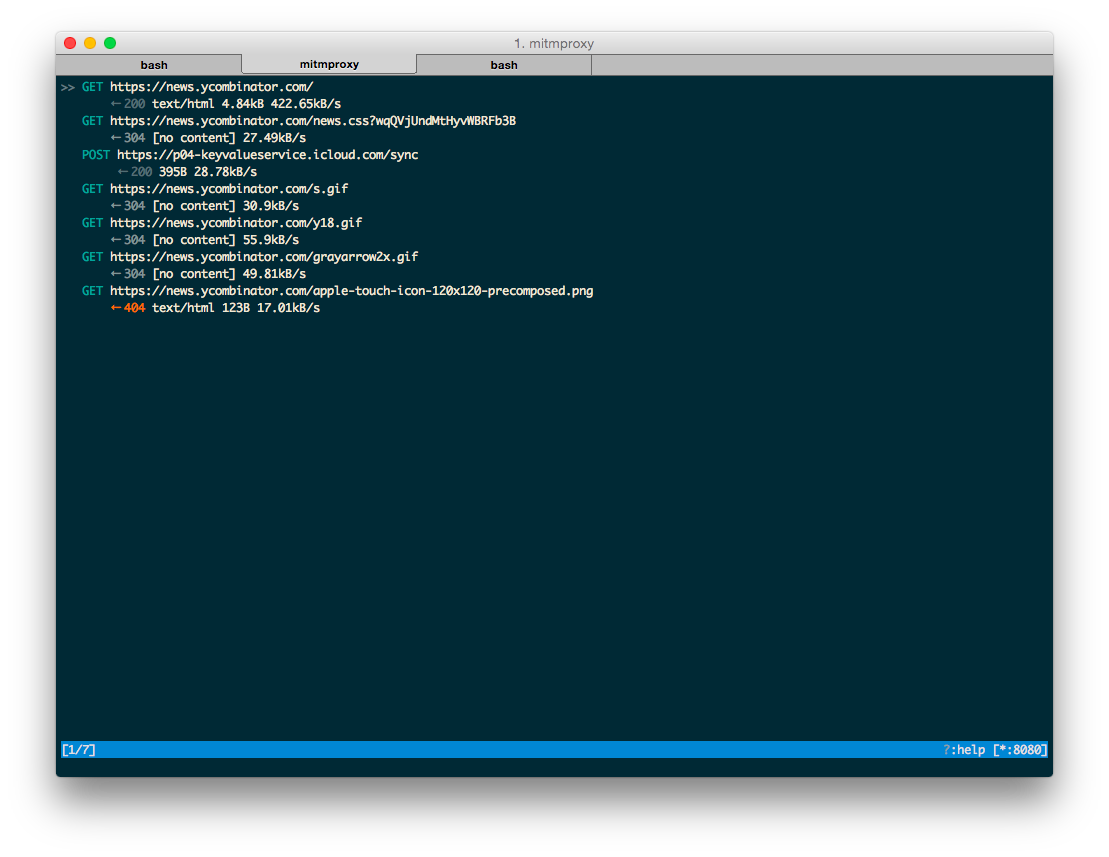

To monitor intercepted requests, launch mitmproxy and connect your phone (default port: 8080).

Open a website in your mobile browser. You should see the traffic in mitmproxy.

With everything confirmed, it’s time to explore the target API. Simply use the app and observe the API endpoints and request structures.

Reverse engineering software APIs is not formulaic; intuition and assumptions play a big role.

I focus on replicating API calls and experimenting. Replaying captured requests in mitmproxy is a good start (press ‘r’). Identify mandatory headers first. Mitmproxy simplifies this: ’e’ enters edit mode, and ‘h’ modifies headers. Vim users will appreciate the shortcuts. Browser extensions like Postman can test APIs, but they often add unnecessary headers. I recommend sticking with mitmproxy or curl.

I wrote a script to read mitmproxy dumps and generate curl commands: https://gist.github.com/nderkach/bdb31b04fb1e69fa5346

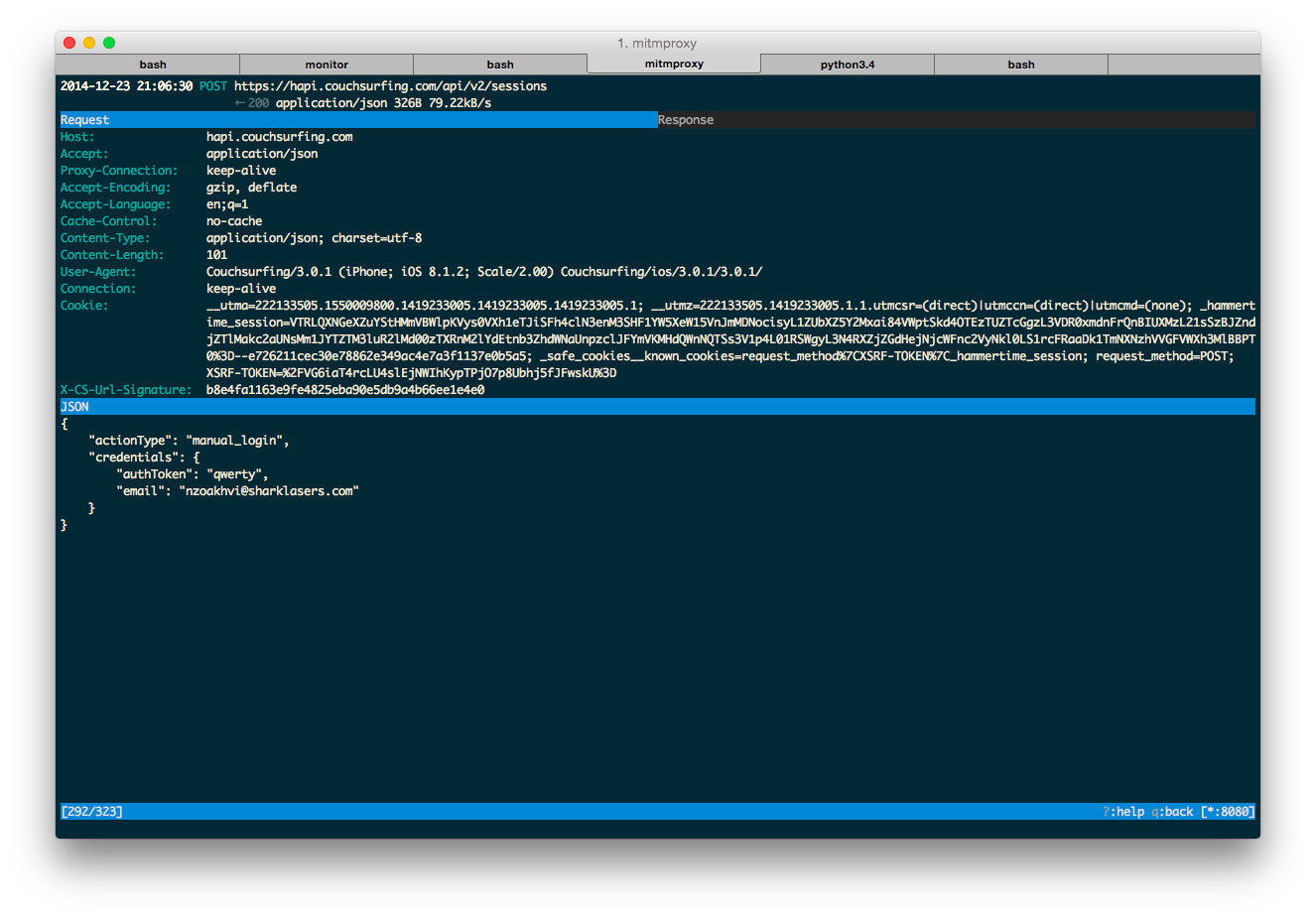

Let’s examine the login request.

| |

The mandatory X-CS-Url-Signature header, unique for each request, immediately stood out. Replaying a request after a delay revealed no server-side timestamp check. Next: deciphering the signature’s calculation.

I decided to reverse-engineer the binary to understand the algorithm. Naturally, with my iPhone experience and device, I started with the iPhone ipa file (app deliverable). Decrypting it required a jailbroken phone. Time for a detour!

Then, I remembered their Android app. While hesitant due to my lack of Android/Java knowledge, I saw a learning opportunity. Decompiling Java bytecode into readable code turned out to be easier than deciphering heavily optimized iPhone machine code.

An apk (Android app file) is essentially a zip archive. Unzip it to find classes.dex, containing Dalvik bytecode (used to run translated Java code on Android).

To decompile .dex into .java, I used dex2jar. The output .jar file can be decompiled with various tools, including Eclipse and IntelliJ IDEA. Most tools produce comparable results. We don’t need to recompile the code, just analyze it.

I tried these tools:

CFR and FernFlower worked best. JD-GUI failed on crucial parts, rendering it useless. Luckily, the Java code seemed unobfuscated, though tools like ProGuard http://developer.android.com/tools/help/proguard.html exist for that purpose.

Java decompilation is beyond this tutorial’s scope - plenty of resources are available. Let’s assume you successfully decompiled and deobfuscated the code.

I’ve compiled the relevant X-CS-Url-Signature calculation code here: https://gist.github.com/nderkach/d11540e9af322f1c1c74

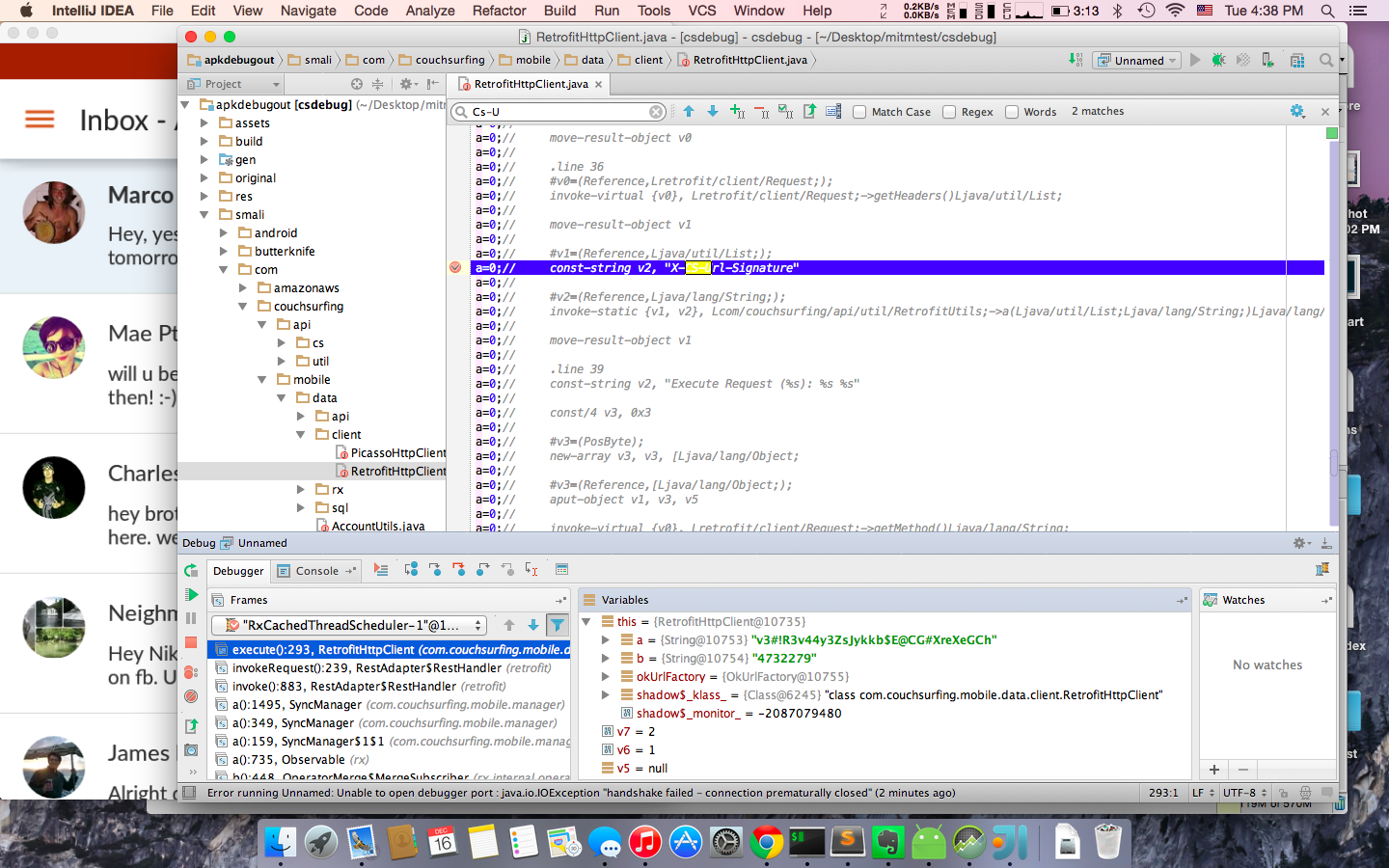

I searched for X-CS-Url-Signature, finding it in RetrofitHttpClient. A call to the EncUtils module seemed interesting. It turned out they’re using HMAC SHA1. HMAC ensures message integrity (preventing tampering) and authentication by hashing a message using a cryptographic function (SHA1 in this case).

We need two things for X-CS-Url-Signature: the private key and the encoded message (likely based on the HTTP request payload and URL).

| |

In the code, a is the message, s is the key, and a2 (after two EncUtils calls) is the HMAC SHA1 hex digest.

The key was easily found - stored in plain text within ApiModule and used to initialize RetrofitHttpClient.

| |

The code shows that the string literal above is used as the HMAC key, unless this.b is defined. If so, this.b is appended with a dot.

| |

The code didn’t reveal how this.b is initialized (I only found its usage in a method with the signature this.a(String b), but no calls to it).

| |

I encourage you to explore the decompiled code and discover it yourself!

The message was straightforward: the URL path (/api/v2/sessions) concatenated with the JSON payload (if any).

| |

The exact HMAC calculation remained unclear from the code. I decided to rebuild the app with debugging symbols for deeper analysis. I used apktool https://code.google.com/p/android-apktool/ to disassemble the Dalvik bytecode using smali https://code.google.com/p/smali/, following the guide at https://code.google.com/p/android-apktool/wiki/SmaliDebugging.

After building, the apk needs to be signed and installed. Lacking an Android device, I used the Android SDK emulator. Here’s a simplified process:

| |

I used the built-in Android emulator with an Atom x86 virtual image and HAXM for smooth performance.

| |

This guide explains virtual image setup: http://jolicode.com/blog/speed-up-your-android-emulator

Ensure HAXM is enabled by checking for “HAX is working and emulator runs in fast virt mode” on emulator startup.

I installed the apk in the emulator and ran the app. Following the apktool guide, I connected IntelliJ IDEA’s remote debugger to the emulator and set breakpoints:

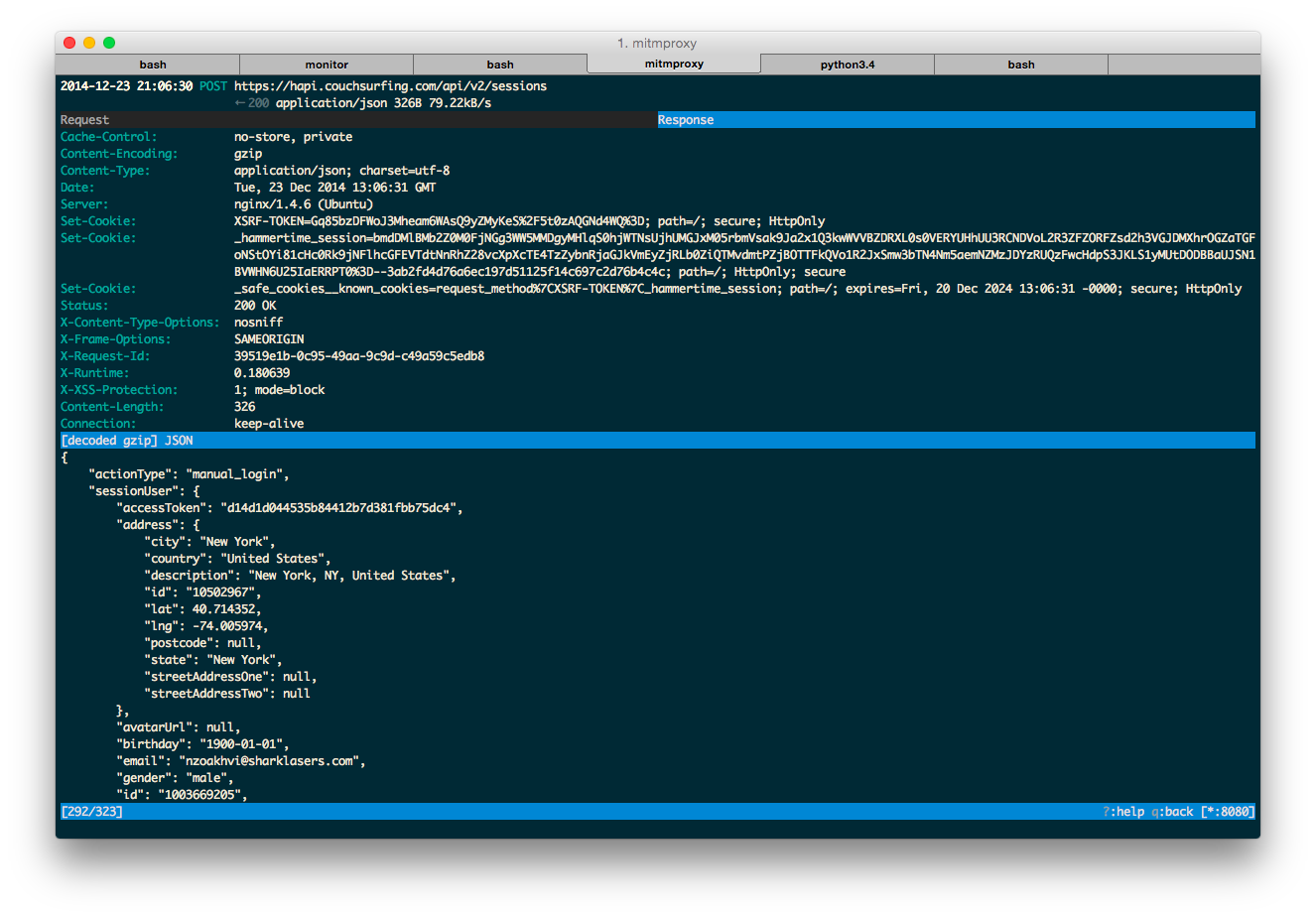

Using the app, I confirmed that the private key initializing RetrofitHttpClient is used for the login request’s HMAC signature. The login response includes a user ID and X-Access-Token. The access token authorizes subsequent requests. Their HMAC calculation is identical to the login request, but the key is the original private key appended with .<user_id>.

After authorization, the app sends this request:

| |

Empirically, this request is optional for authentication. Bonus points if you figure out its purpose!

Once authenticated, you can fetch any user’s profile:

| |

I noticed that profiles are updated via PUT requests. I tried updating another profile with the same request, but it was unauthorized, indicating basic security measures are in place.

I wrote a Python script for logging in with couchsurfing.com credentials and retrieving user profiles: https://gist.github.com/nderkach/899281d7e6dd0d497533. Here’s the Python API wrapper: https://github.com/nderkach/couchsurfing-python, also available on PyPI (pip install couchsurfing).

What’s Next?

I’m unsure about my next steps with this API. User profiles no longer allow HTML code, so I’ll need a new approach to the old problem. I’ll continue developing the Python wrapper if there’s demand, assuming couchsurfing.com cooperates. I haven’t explored the API extensively, only testing basic vulnerabilities. It seems secure, but could it expose data inaccessible through the website? Regardless, my reverse engineering enables you to build alternative clients for Windows Phone, Pebble, or even your smart-couch!

A Final Thought

Here’s a question: why not make your API public? Even if I hadn’t cracked it, scraping the website would still be possible - slower and harder to maintain, but possible. Wouldn’t they prefer API consumers over web scrapers? Public APIs empower third-party developers to enhance their product and create value-added services. While maintaining a public API might seem costlier, the benefits of community-driven development outweigh the costs.

Can you completely prevent third-party access to a private API? I doubt it. SSL pinning could prevent sniffing with simple proxies, but determined hackers with resources will always find ways to reverse-engineer binaries and obtain keys/certificates. Assuming client-side security is flawed. API clients are vulnerabilities.

Private APIs signal distrust towards users. Sure, you can try to protect them, but wouldn’t it be better to implement basic API security and focus on improving the software and user experience?

Couchsurfing, please, open the API!