In the world of modern web development, caching stands out as a potent tool for enhancing speed. When implemented effectively, it can significantly boost your application’s overall performance. However, incorrect implementation can lead to disastrous consequences.

Cache invalidation is widely recognized as one of the most challenging problems in computer science, alongside naming things and off-by-one errors. A straightforward, albeit inefficient, solution is to invalidate everything whenever any change occurs. However, this approach undermines the very purpose of caching. The key is to invalidate the cache only when absolutely essential.

To fully leverage caching, you must exercise precision in what you invalidate, preventing your application from squandering valuable resources on redundant tasks.

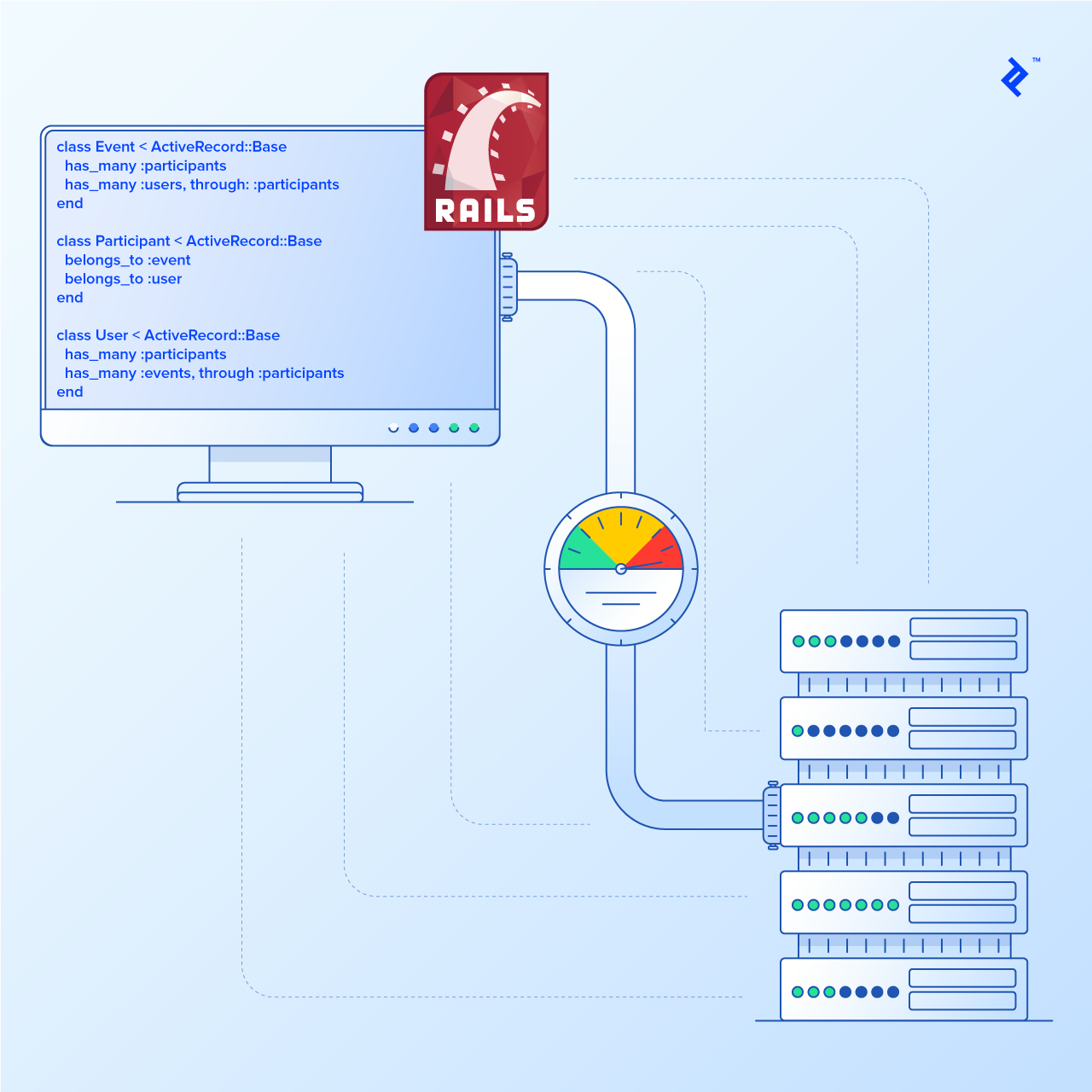

This blog post will guide you through a technique for achieving greater control over Rails cache behavior, specifically implementing field-level cache invalidation. This technique relies on Rails ActiveRecord and ActiveSupport::Concern, along with modifications to the touch method’s behavior.

The insights shared in this post stem from my recent project experiences, where implementing field-level cache invalidation led to substantial performance gains by reducing unnecessary cache invalidations and redundant template rendering.

Rails, Ruby, and Performance

While not the fastest language, Ruby excels in development speed. Its metaprogramming capabilities and built-in domain-specific language (DSL) features empower developers with remarkable flexibility.

Studies like Jakob Nielsen’s study highlight that tasks exceeding 10 seconds lead to a loss of focus, and regaining focus consumes time, ultimately incurring unexpected costs.

Unfortunately, Ruby on Rails makes it surprisingly easy to surpass this 10-second threshold during template generation. While this might not be evident in simple applications or small-scale projects, real-world projects with complex pages can experience significant slowdowns due to template generation.

This was precisely the challenge I faced in my project.

Straightforward Optimizations

So, how do we accelerate things? The answer lies in benchmarking and optimization.

Two highly effective optimization steps in my project were:

- Eliminating N+1 queries

- Implementing an efficient caching mechanism for templates

N+1 Queries

Resolving N+1 queries is relatively straightforward. By analyzing your log files for repetitive SQL queries like the ones shown below, you can replace them with eager loading:

| |

A gem called bullet can assist in identifying these inefficiencies. Alternatively, you can manually review use cases and inspect logs for the aforementioned pattern. Eliminating N+1 inefficiencies ensures you don’t overload your database, significantly reducing the time spent on ActiveRecord operations.

These changes noticeably improved my project’s speed. However, I aimed to further reduce the loading time. There was still room for optimization in template rendering, which is where fragment caching came into play.

Fragment Caching

Fragment caching significantly reduces template rendering time. However, the default Rails cache behavior wasn’t sufficient for my project’s requirements.

Rails fragment caching is based on a brilliant concept, providing a simple yet effective caching mechanism.

The creators of Ruby On Rails have authored an insightful article in Signal v. Noise on how fragment caching works.

Imagine a section of your user interface displaying fields from an entity.

- Upon page load, Rails generates a

cache_keybased on the entity’s class andupdated_atfield. - It then checks the cache for content associated with this key.

- If no cached content exists, the HTML fragment for that section is rendered and stored in the cache.

- If cached content exists, the view is rendered using that content.

This approach eliminates the need for explicit cache invalidation. When the entity is modified, reloading the page triggers the rendering and caching of new content for that entity.

Rails also offers a convenient way to invalidate parent entity caches when a child entity changes:

| |

Including this in a model automatically “touches” the parent when the child is “touched.” More information about the touch method can be found here. This provides a simple and efficient way to invalidate caches for both parent and child entities simultaneously.

Caching Challenges in Rails

However, Rails caching is primarily designed for user interfaces where the HTML fragment representing the parent entity solely contains fragments representing its child entities. In other words, child entity fragments in this paradigm cannot include fields from the parent entity.

Real-world applications often deviate from this structure, requiring you to implement solutions that go beyond this limitation.

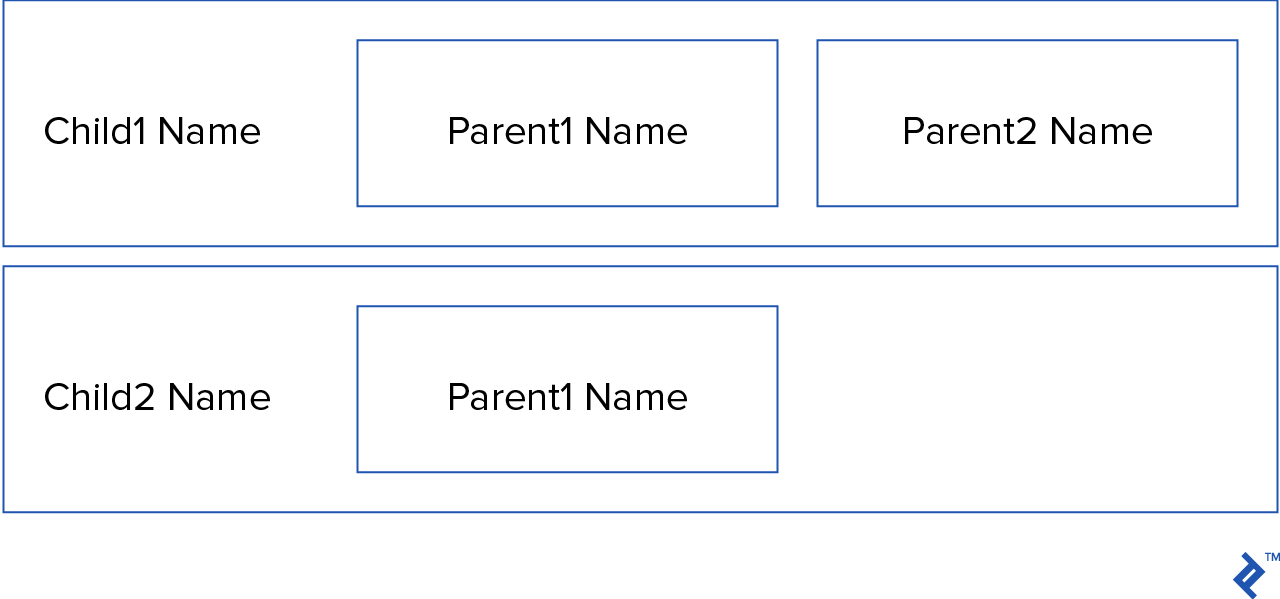

Consider a scenario where your user interface displays fields from a parent entity within the HTML fragment representing a child entity.

If the child entity’s fragment includes fields from the parent, Rails’ default cache invalidation behavior becomes problematic.

Modifying these parent entity fields necessitates touching all child entities associated with that parent to invalidate their caches. For instance, modifying Parent1 would require invalidating the caches for both Child1 and Child2 views.

This can create a significant performance bottleneck, as touching every child entity upon parent modification leads to numerous unnecessary database queries.

A similar issue arises when entities associated through a has_and_belongs_to association are displayed in a list, and modifying these entities triggers a cascade of cache invalidations across the association chain.

| |

In this user interface, it wouldn’t make sense to touch the participant or event when the user’s location changes. However, modifying the user’s name should logically touch both the event and the participant.

Therefore, the techniques discussed in the Signal v. Noise article prove inefficient for certain UI/UX scenarios, as illustrated above.

While Rails excels in simplicity, real-world projects often present unique complexities.

Field-Level Cache Invalidation in Rails

To address these challenges, I’ve been utilizing a concise Ruby DSL in my projects. This DSL enables declarative specification of fields that trigger cache invalidation through associations.

Let’s explore some examples where this approach proves beneficial:

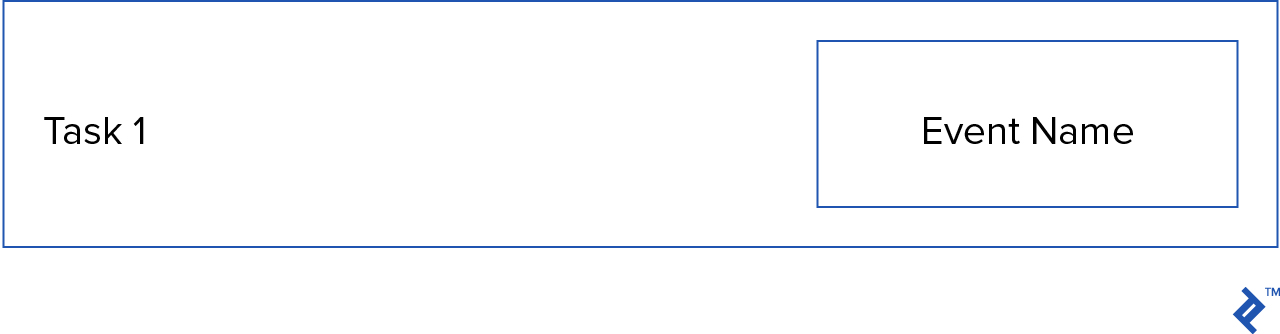

Example 1:

| |

This snippet leverages Ruby’s metaprogramming and inner DSL capabilities.

Specifically, only changes to the event’s name will invalidate the fragment cache of its associated tasks. Modifying other event fields, such as purpose or location, won’t affect the task’s fragment cache. This is what I refer to as “field-level fine-grained cache invalidation control.”

Example 2:

Consider an example involving cache invalidation across a has_many association chain.

The user interface fragment below displays a task and its owner:

In this scenario, the task’s HTML fragment should only be invalidated when the task itself changes or when the owner’s name is modified. Changes to other owner fields, such as time zone or preferences, shouldn’t impact the task’s cache.

This can be achieved using the following DSL:

| |

Implementing the DSL

The core of this DSL lies in the touch method. Its first argument is an association, and the second argument is an array of fields that trigger a “touch” on that association:

| |

This method is provided by the Touchable module:

| |

The key aspect here is storing the touch call’s arguments. Before saving the entity, we mark the association as dirty if a specified field has been modified. After saving, we “touch” entities within dirty associations.

The private section of the concern looks like this:

| |

The check_touchable_entities method checks if a declared field has changed. If so, it marks the association as dirty by setting meta_info[association] to true.

After saving the entity, we iterate through dirty associations, touching their associated entities if necessary:

| |

And that’s it! You can now implement field-level cache invalidation in Rails using a simple DSL.

Conclusion

Rails caching offers a relatively easy way to enhance application performance. However, real-world applications can present unique complexities. While the default Rails cache behavior works effectively in most cases, certain scenarios benefit from fine-tuning cache invalidation.

Armed with the knowledge of implementing field-level cache invalidation in Rails, you can now prevent unnecessary cache invalidations in your application, optimizing its performance for various scenarios.