What makes the Vulkan API special, and why is it creating a buzz among developers and gamers alike?

In a nutshell, the Vulkan API is a streamlined, powerful tool for building 3D graphics and compute applications. Think of it as the next evolution of OpenGL, borrowing some inspiration from AMD’s Mantle API. Vulkan promises a range of benefits, including smoother performance across different devices, better use of multi-core processors, reduced strain on your CPU, and a bit of cleverness in how it interacts with different operating systems. It’s also designed to simplify the creation and pre-compilation of drivers, allowing for shaders written in various programming languages.

That’s the gist in under 100 words. If your curiosity is piqued, read on to delve deeper into the fascinating world of the Vulkan graphics API, a technology poised to shape the future of graphics for years to come.

The Genesis of Vulkan API

Vulkan was originally announced by the Khronos Group in March 2015, with the goal of launching later that year. In case you’re not acquainted with Khronos, it’s a non-profit organization formed 15 years ago by industry giants like ATI (now part of AMD), Nvidia, Intel, Silicon Graphics, Discrete, and Sun Microsystems. Even if Khronos doesn’t ring a bell, you’ve likely encountered their work, including standards like OpenGL, OpenGL ES, WebGL, OpenCL, SPIR, SYCL, WebCL, OpenVX, EGL, OpenMAX, OpenVG, OpenSL ES, StreamInput, COLLADA, and glTF.

With that introduction out of the way, let’s dive straight into the heart of the API itself.

Unlike its predecessors, Vulkan is built from the ground up to work seamlessly across various devices – from mobile phones and tablets to gaming consoles and powerful desktops. Its modular design allows for a core architecture that can be extended and customized, enabling features like code verification, debugging, and performance profiling without sacrificing speed. Khronos highlights that this layered approach will provide remarkable flexibility, encourage innovation in cross-vendor GPU tools, and give sophisticated game engines the fine-grained GPU control they crave.

While terms like “flexible,” “extensible,” and “modular” might sound like marketing jargon, Vulkan truly embodies these concepts. It’s designed to be an API for everyone, from kids enjoying games on their phones to professionals designing complex structures and games on high-end workstations.

Theoretically, Vulkan could even be harnessed in parallel computing systems to manage vast networks of GPU cores, powering everything from tiny wearable devices and drones to 3D printers, cars, VR headsets, and virtually anything else equipped with a compatible GPU.

If you’re eager to explore the technical intricacies, I recommend checking out the official Vulkan overview in PDF.

The Legacy of AMD Mantle

Vulkan’s emphasis on direct hardware access might ring a bell if you’ve been keeping up with AMD’s GPU developments in recent years. Back in 2013, AMD raised eyebrows with the announcement of its Mantle API. However, the company surprised everyone again in March 2015 by deciding to discontinue Mantle, choosing not to release a public SDK for Mantle 1.0.

In essence, Mantle promised significant performance and efficiency gains, particularly by reducing the load on CPUs. Gamers could potentially opt for slightly less powerful processors and invest more in high-end graphics cards. This strategy seemed advantageous for AMD, as the company hadn’t been a major player in the high-end CPU market for some time, despite offering competitive GPUs.

Just as AMD fans were mourning the loss of Mantle, it experienced a resurrection of sorts. The good news came in the form of a blog post, penned by AMD VP of Visual and Perceptual Computing, Raja Koduri.

Putting the dramatic comparisons aside, Koduri and his team achieved something significant. While Mantle itself didn’t become the new industry standard, it laid the groundwork for Vulkan. The key difference? Vulkan isn’t limited to AMD’s GCN hardware; it’s designed to function across a wide range of GPUs from different manufacturers.

Having a single, efficient graphics API that operates seamlessly across various operating systems and hardware platforms is undoubtedly preferable to dealing with a fragmented landscape of proprietary APIs tailored to specific GPU architectures and OSes.

Vulkan API takes the core concepts of Mantle and makes them accessible to everyone, fostering a more inclusive and efficient graphics ecosystem.

It’s also worth noting that Mantle played a role in motivating Microsoft and Khronos to address the increasing complexity and inefficiency of DirectX and OpenGL.

A Comparison: Vulkan vs. OpenGL

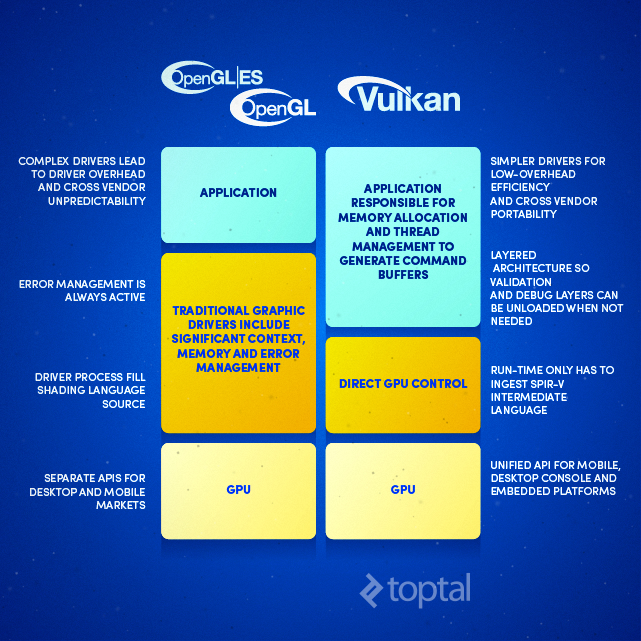

Let’s clarify the fundamental differences between Vulkan and OpenGL. Khronos provided a straightforward illustration showcasing how much driver overhead could be minimized with the new API.

Vulkan allows applications to interact more directly with hardware, minimizing the need for extensive memory and error management, as well as simplifying shading language source code. This translates to drivers that are more efficient and streamlined. Vulkan will exclusively utilize the SPIR-V intermediate language, and its unified API approach across mobile, desktop, and console platforms should attract more attention and support from developers.

But does this shift simply transfer the workload to game developers? While they gain the ability to utilize hardware more effectively, what about their own development time? This is where the layered ecosystem approach comes into play.

Developers can choose from three different levels, or tiers, of the Vulkan ecosystem:

- Direct Vulkan usage for maximum control and flexibility.

- Utilizing Vulkan libraries and layers to accelerate development.

- Leveraging a Vulkan-optimized game engine.

The first option caters to specialized use cases, perhaps for creating benchmarking software. Khronos envisions the second option as a fertile ground for innovation, as many tools and layers will be open source, easing the transition from OpenGL. This approach would be particularly useful for publishers looking to update and optimize existing OpenGL titles.

The final option, adopting a fully optimized Vulkan game engine, might be the most appealing for many, as the heavy lifting is handled by industry heavyweights like Unity, Oxide, Blizzard, Epic, EA, Valve, and others.

Here’s a quick comparison between OpenGL and Vulkan:

| OpenGL | Vulkan |

|---|---|

| Originally created for graphics workstations with direct renderers, split memory. | A better match for modern platforms, including mobile platforms with unified memory and tiled rendering support. |

| Driver handles state validation, dependency tracking, error checking. This may limit and randomise performance. | The application has direct and predictable control over the GPU via an explicit API. |

| Obsolete threading model does not allow generation of graphics commands in parallel to command execution. | API designed for multi-core, multi-thread platforms. Multiple command buffers can be created in parallel. |

| API choices can be complex, syntax evolved over twenty years. | Removal of legacy requirements simplifies API design, simplifies usage guidance, reduces specification size. |

| Shader language compiler is a part of the driver, and it only supports GLSL. The shader source has to be shipped. | SPIR-V is the new compiler target, enabling front-end language flexibility and reliability. |

| Developers have to take into account implementation variability between vendors. | Due to the simpler API and common language front-ends, more rigorous testing will increase cross-vendor compatibility. |

In reality, directly comparing the two might not be entirely fair. Vulkan, being a descendant of Mantle, represents a fresh start, while OpenGL carries the weight of 20 years of legacy. Vulkan’s purpose is to shed this baggage, simplifying testing, streamlining drivers, and enhancing shader program portability through the SPIR-V intermediate language.

This brings us to our next question: What does Vulkan mean for developers in practical terms?

SPIR-V: Reshaping the Language Landscape

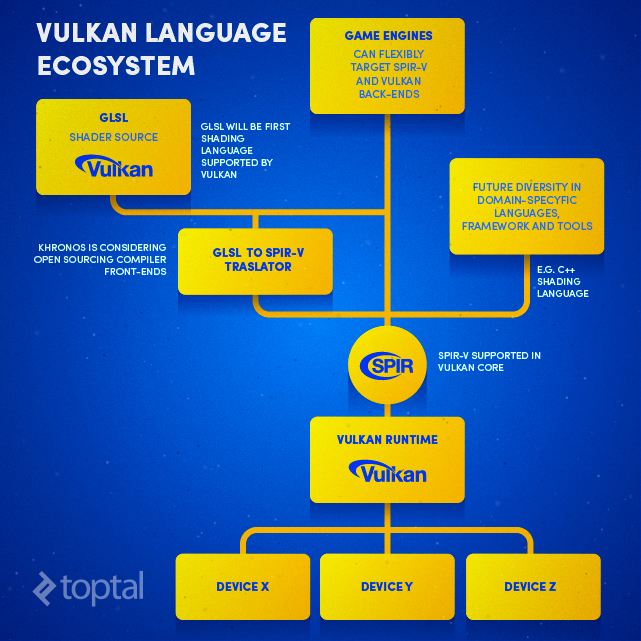

What role does SPIR-V play in all of this, and what about the venerable GLSL shading language?

GLSL isn’t going anywhere just yet; it will remain the initial shading language supported by Vulkan. A GLSL to SPIR-V translator will handle the conversion process, making SPIR-V ready for use with the Vulkan runtime. Game developers can leverage SPIR-V and Vulkan back-ends, potentially relying on open-source compiler front-ends. Beyond GLSL, Vulkan can work with OpenCL C kernels, and support for C++ is in progress. There’s also the potential for future integration with domain-specific languages, frameworks, and tools. Khronos even hints at the possibility of developing entirely new, experimental languages.

Regardless of the path developers choose, everything ultimately leads to Vulkan via SPIR-V, enabling deployment across a wide array of devices.

SPIR-V aims to enhance portability in three key ways:

- Shared tools

- A single toolset for a given Independent Software Vendor (ISV)

- Simplified design

With SPIR-V, there’s no need for every hardware platform to have its own high-level language translator, streamlining development.

An ISV can utilize a single toolset to generate SPIR-V, circumventing portability hurdles associated with high-level languages.

SPIR-V’s streamlined design, compared to typical high-level languages, simplifies implementation and processing.

Performance optimizations can be achieved in several ways, depending on how Vulkan is implemented:

- Eliminating the compiler front-end allows for more offline processing

- Offline optimization passes can be resolved faster

- Multiple source shaders can be condensed into a single intermediate language instruction stream

While Khronos doesn’t provide specific performance figures, noting that results will vary depending on implementation, the potential for improvement is evident. For a deeper dive into the technical details, refer to the SPIR-V white paper.

A Developer-Friendly Future with Vulkan?

I’ve highlighted a number of features that position Vulkan and SPIR-V for success among developers, a sentiment echoed by Khronos. The ability to target multiple platforms using the same tools and skillset is particularly enticing, especially as performance disparities between platforms continue to shrink.

While developing AAA games for PCs will remain a complex and resource-intensive undertaking, mobile platforms and integrated GPUs found in the latest Intel and AMD processors offer substantial graphics capabilities for casual gaming. Additionally, smaller independent developers and freelancers are more likely to focus on cross-platform casual games rather than AAA titles produced by major studios.

Khronos outlines the following advantages of SPIR-V for developers:

- A single front-end compiler can be used across multiple platforms, minimizing cross-vendor portability issues

- Runtime shader/kernel compilation time is reduced, as drivers only need to process SPIR-V

- Distributing shader/kernel source code is no longer necessary, enhancing IP protection

- Drivers are simplified and more robust, as they no longer require embedded front-end compilers

- Developers gain better insight into memory allocation, enabling optimizations

While this all sounds promising, it’s important to remember that Vulkan is still a work in progress.

Vulkan: Progress and Potential

Vulkan is still under development, with the full specification expected by the end of the year. However, early demonstrations suggest that the new API can unlock substantial performance gains even on existing hardware.

One compelling example comes from Imagination Technologies, a prominent mobile GPU developer. Their GPU designs power all iOS devices, along with numerous ARM-based System-on-Chips and even some low-power Intel x86 chips.

Last week, Imagination Technologies published a blog post showcasing the performance improvements enabled by Vulkan. They chose an unconventional test platform: a Google Nexus Player powered by a relatively uncommon Intel quad-core processor and a PowerVR G6430 GPU. The device was tested with the latest Vulkan API driver for PowerVR GPUs, compared against a reference run using OpenGL ES 3.0. The performance difference was astounding.

The test scene consists of 400,000 objects with varying levels of detail, ranging from 13,000 to 300 vertices. The wide shot displays an estimated one million triangles, some alpha effects on plants, and around ten different textures for the gnomes and plants. Each object type utilizes a different shader, and the gnomes are not instanced. This means that each draw call could potentially represent a unique object with distinct materials, though the final visual outcome would be similar.

However, a word of caution: don’t expect to see these exact performance gains in real-world scenarios. Imagination Technologies intentionally crafted an extreme scenario to highlight Vulkan’s capabilities and push it to its limits. In this particular test, those limits favor Vulkan over OpenGL ES. It’s also crucial to note that this test is GPU-bound, meaning the GPU is the limiting factor, not the CPU. Despite this, it effectively illustrates Vulkan’s superior CPU utilization.

Vulkan’s Secret to Reduced CPU Load

Recall the OpenGL vs. Vulkan table, specifically the mention of tiled rendering? To summarize, Imagination Technologies employed Vulkan to group draw calls into tiles, rendering one tile at a time. Depending on the tile’s position within the frame being rendered, it might enter or exit the field of view, change its level of detail, and so on. In OpenGL ES, all draw calls are dynamic, submitted with each frame based on what’s visible. Previously executed draw calls cannot be cached.

Consequently, OpenGL ES requires numerous transitions into kernel mode to modify and validate the driver’s state. Vulkan avoids this by using pre-generated command buffers, reducing CPU overhead and eliminating the need for validation or compilation during rendering. The Imagination team described the ability to reuse command buffers as “useful in some circumstances” and potentially “highly beneficial” in many games and applications.

Another significant factor is parallel buffer generation, allowing Vulkan to fully utilize multi-core CPUs. OpenGL ES was conceived before multi-core mobile chips became prevalent. Over the past three years, the industry has witnessed a shift from dual-core to quad-core, and now even eight and ten-core CPU configurations, with Apple’s A-series SoCs and Nvidia’s Denver-based Tegra chips as notable exceptions.

Think of Vulkan as a modern turbocharged engine: it stores and reuses energy like a turbocharger and intercooler (command buffers), and it efficiently utilizes all available cylinders (parallel buffer generation). In contrast, OpenGL ES resembles an old, single-cylinder engine struggling to keep up.

The result? A significantly more efficient environment that maximizes hardware utilization, unlike OpenGL ES, which often becomes bottlenecked by the CPU. Vulkan achieves similar performance levels while keeping the CPU running at lower speeds, reducing power consumption and heat generation.

Potential Drawbacks of Vulkan API (Spoiler: Not Many)

It’s essential to consider both the advantages and disadvantages of the Vulkan API. Thankfully, the drawbacks are few and far between, mostly minor with perhaps one or two potentially significant considerations.

- Increased code complexity in certain scenarios

- Time-to-Market

- Level of industry adoption

- Limited relevance or effectiveness on certain platforms (desktops)

- Convincing developers to embrace Vulkan on specific platforms

- Compatibility limitations with older hardware

Implementing some of Vulkan’s advanced features might require substantial coding effort, though new driver updates from industry leaders should simplify the process.

Time-to-market and adapting older applications and games to Vulkan are also concerns. As Vulkan is still in its early stages, with initial specifications and implementations expected by late 2015, widespread real-world adoption might not occur before mid-2016.

While industry support shouldn’t be a major obstacle, given that Vulkan is a Khronos standard, it will take time for adoption to gain momentum. This is one reason why this discussion has focused on mobile platforms; mobile software and hardware evolve rapidly. It might be a few quarters before Vulkan makes a significant impact on the desktop market, which has additional complexities like professional application support and a demanding gaming community. However, Vulkan’s roots in AMD’s Mantle are encouraging.

Although Vulkan excels in CPU-bound scenarios, especially on multi-core mobile SoCs, its benefits might be less pronounced on desktop platforms. Desktops generally handle multi-core processors more efficiently, and most graphically demanding applications are GPU-bound.

Until the Vulkan ecosystem matures, some developers might hesitate to adopt it. Many simply lack the time for experimentation and only invest in learning new technologies when absolutely necessary. Devoting significant resources to adapting existing mobile games for Vulkan at this early stage might not be feasible for many developers and publishers.

Compatibility with older hardware could be another concern. Vulkan requires OpenGL ES 3.1 or OpenGL 4.1 compatible hardware, along with updated drivers. For instance, Imagination Technologies’ PowerVR Series 6 GPUs support Vulkan, while Series 5 GPUs do not. Qualcomm’s Adreno 400 series supports OpenGL ES 3.1, but the 300 series does not. ARM’s Mali T600 and T700 series support OpenGL ES 3.1, but older T400 series designs lack support. Fortunately, by the time Vulkan becomes widely adopted, most devices with incompatible GPUs will likely be outdated. This includes devices like the iPhone 5/5C, fourth-generation iPad, and Samsung devices using certain Exynos 5000 series chips. Qualcomm-based devices might face a greater challenge, as Adreno 300 series GPUs are found in relatively recent and popular devices like the Snapdragon 410, Snapdragon 600, Snapdragon 800, and 801. However, many of these devices might be phased out by the time Vulkan becomes mainstream.

The Future of Graphics Rendering

It’s too early to definitively declare Vulkan a revolutionary technology, but its potential is undeniable. Based on years of observing the GPU industry, I believe Vulkan will have a significant impact, starting with mobile platforms and eventually reshaping the desktop landscape.

As Vulkan-optimized drivers, game engines, and games emerge, new hardware will arrive to take advantage of these advancements. And I’m not just referring to incremental hardware upgrades. Mobile SoC development has faced some recent stagnation, but 2016 promises to be a pivotal year. The arrival of 14/16nm FinFET manufacturing processes will make powerful and efficient hardware more accessible, moving beyond flagship devices to mainstream adoption.

Developers will have access to significantly more capable hardware, and a new, efficient graphics API like Vulkan will be the perfect complement. Hopefully, hardware manufacturers will shift their focus away from using display resolution as a primary marketing tactic. Excessively high resolutions do little to enhance visual quality while needlessly consuming power. Unfortunately, as the average consumer seems fixated on bigger numbers, this trend might not change anytime soon.