“People who write for a living are all broke.” “Writing is more of a calling than an actual job.” “Writing might be enjoyable, but it won’t make you rich.” That’s all rubbish.

Writing is not fun. It’s a daily grind. Occasionally, it’s not too bad. But most of the time it’s really challenging. It demands 100% of your attention, focus, and energy. And it can be profitable. However, that’s only if you approach it the right way. Do you want to be a freelance writer? Here are seven genuine tips for finding and keeping freelance writing jobs (coming from an accidental writer who has made a good living from it).

1. Get Paid First

Content is not king. Cash flow is. Your skills don’t mean much if you can’t pay the bills.

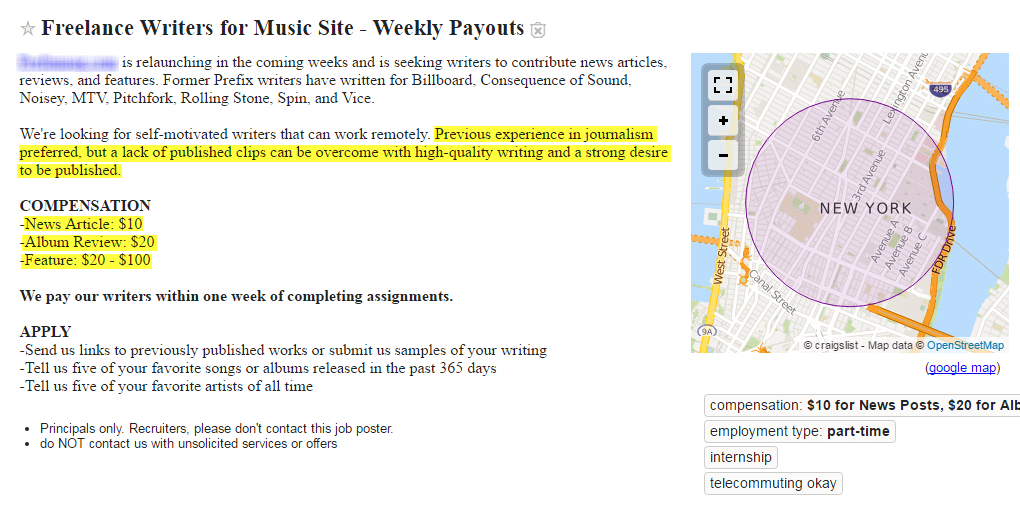

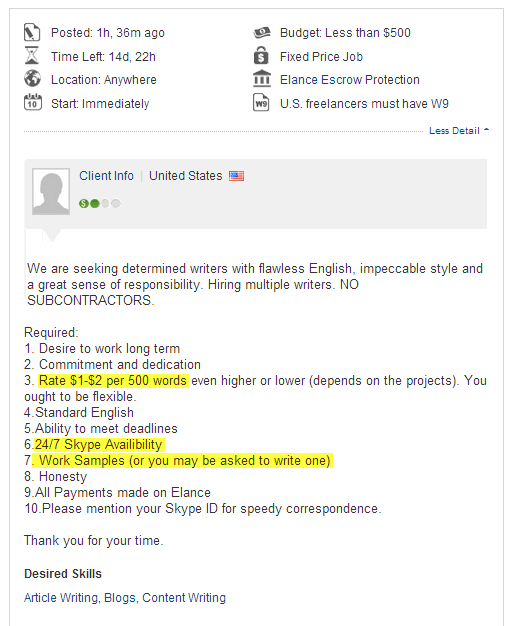

When you’re just starting out as a freelance writer, your main challenge is getting noticed. So you find work where it’s easy to find: job boards. There’s a constant stream of freelance writing gigs available. It’s like picking low-hanging fruit—easy to reach and grab as soon as it’s ripe. But here’s the catch. If you ever want to escape the never-ending cycle of job boards, you need to abandon them as soon as possible. (This includes content mills like iWriter, Upwork, Craigslist, or even worse, Fiverr.)

Yep, that’s an actual subway ad for Fiverr. Who knew wage slavery could be so glamorous? It’s not that you should never consider them in the future. But don’t rely on these platforms to sustain you in the long run. And here’s why. Problem #1: Job boards are mainly filled with low-paying, generic freelance work. Job boards are like massive cattle calls. A ton of ordinary job posts looking for generic writing from typical writers. Consequently, they are only willing to offer standard rates.

LOL Look, you gotta eat. So if you need the work, go for it. But as you progress, and if you implement the following tips effectively, the work and clients you get from those job boards will only hold you back. Problem #2: You have absolutely no control over the project scope. Job board posts usually outline the work they need. Often, these descriptions are put together by someone with little to no experience in the actual work they’re hiring for. And this creates a few problems.

LOL The most common issue is that the scope of work is often unreasonable and all over the place. The deadlines are impossible to meet. And of course, the rate they offer for this mess is an absolute joke. But in sales, it’s all about positioning. If you’re coming from a job board, your chances of negotiating those terms are next to impossible. But if you get an inquiry directly or through a personal referral, you’re viewed as an expert. And that is crucial for making the leap to well-paid freelance writing.

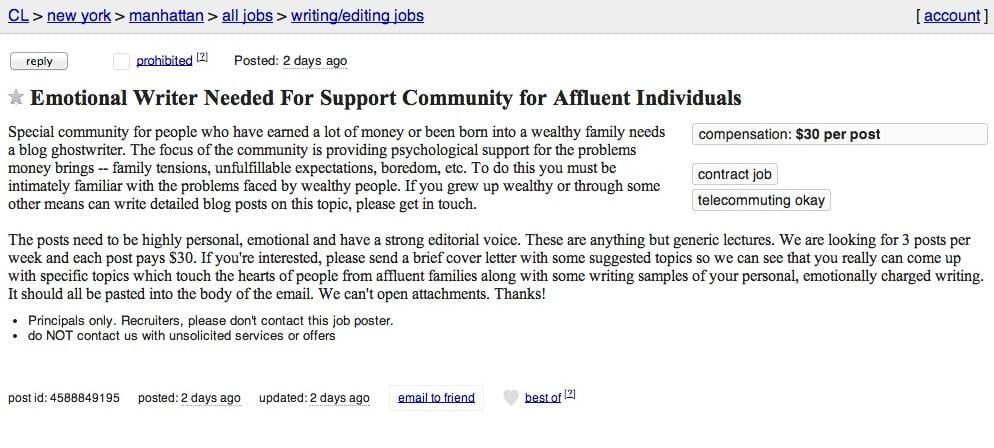

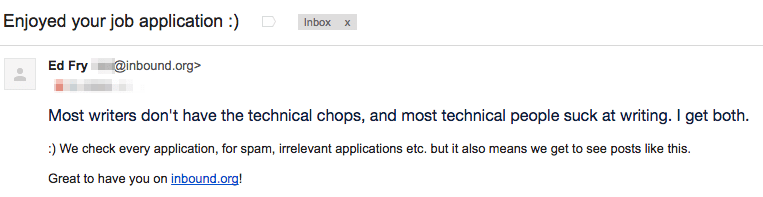

2. Learn to Distinguish Between Good and Bad Work

Some work simply pays the bills. That’s the kind of work you need when you’re starting out. Then there’s work that gets you noticed. That’s the work you need to reach the “next level.” The tough part is knowing when to accept each type. It’s a classic Catch-22. You have to strike a balance between taking on less desirable work and not neglecting the “brand-building” work (which we’ll come back to). Lean too far in one direction or the other, and you’ll find yourself in trouble. The good news is that at a certain point, if you play your cards right, these two types of work will merge. That means the high-quality work will also be the work that pays your bills.

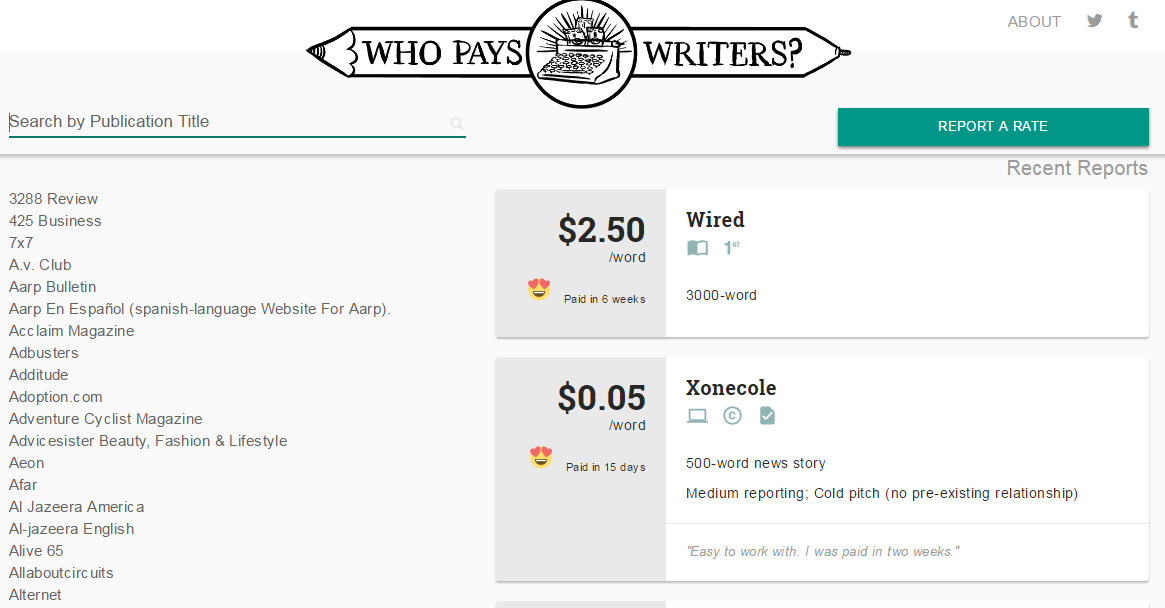

whopayswriters.com is a fantastic source for finding out how much publications pay It turns out your teachers were wrong. There is such a thing as a bad question. And a bad client. And a bad project. Taking on too much soul-crushing work will destroy your ambition. It will crush your chances of making a profit in the future. And it will eat up any free time you might have to go after those bigger, better-paying assignments. The good news for those of us who lean towards words is that freelance math is incredibly simple. There are only two ways to make more money:

- Increase your rates.

- Write more. That’s it. No tricks or shortcuts. At some point, you’ll hit a limit on #2. You should always push to expand that capacity. But you’ll inevitably reach a point where you can’t physically write more than a few thousand words or work more than four to six hours per day. That’s why most writers (and freelancers in general) should prioritize improving #1. They should do it first, but they usually don’t.

LOOOOOOOL Let’s circle back to job boards. Depending on them entirely is a recipe for disaster. But browsing them occasionally is perfectly fine, as long as you know what you’re looking for. Every now and then, you’ll come across a job board posting that really grabs your attention because it’s that rare gem that meets all of your criteria. That’s when selling your services becomes easy. It’s straightforward and doesn’t require any sleazy closing techniques.

- “I’m a perfect fit for this project.”

- “Here are some samples of my work that demonstrate my skills in this area.”

- “I look forward to hearing from you soon.”

However, there is one crucial sales skill you’ll need to master. Managing your pipeline. Sales is a numbers game, so treat it that way.

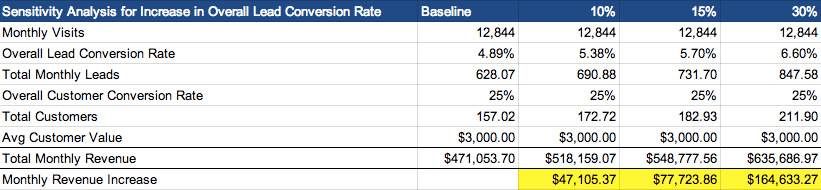

- Determine what success looks like for you. Let’s say your goal is to make $10,000 per month. Great.

- Figure out how much each client is worth. To keep things simple, let’s say each client brings in $1,000.

- This means you’ll need 10 clients over the next few months. And to simplify further, let’s aim for one new client per month.

- Remember, not every lead will convert into a client. It might take 10 leads, or even 30, to land one client.

- Break down your goals into manageable daily and weekly tasks. If you need 30 contacts in 30 days, that’s just one new contact per day.

- So ask yourself: What am I doing today to connect with that one new person? Don’t get bogged down in tactics or specific methods. Send a carrier pigeon if you must! The key is to simply talk to people.

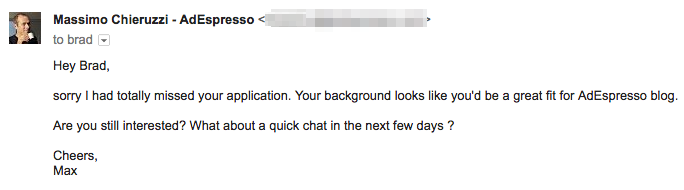

3. Specialize as Soon as Possible

Initially, I mostly wrote to draw attention to myself and my business. My goal was to attract paying clients for various marketing services. Because everyone knows you can’t make any real money from writing… right? My very first paid writing gig was for $0.06 per word. I was clueless about what I was doing and had no idea what a reasonable per-word rate was. (In case you’re wondering, I don’t even think it worked out to minimum wage.) So, no, you can’t make a living from that. But in less than nine months, I was charging $0.30+ per word and earning over six figures annually. And I was only working part-time! All this while I was running another company with employees, clients, and all the headaches that come with it. And on top of that, I had a family with amazing kids, a wife, and a pug. (The pug is the most demanding, by the way.) So, yeah, you can absolutely earn a living from writing. You just need to identify what you’re exceptionally good at and then capitalize on it.

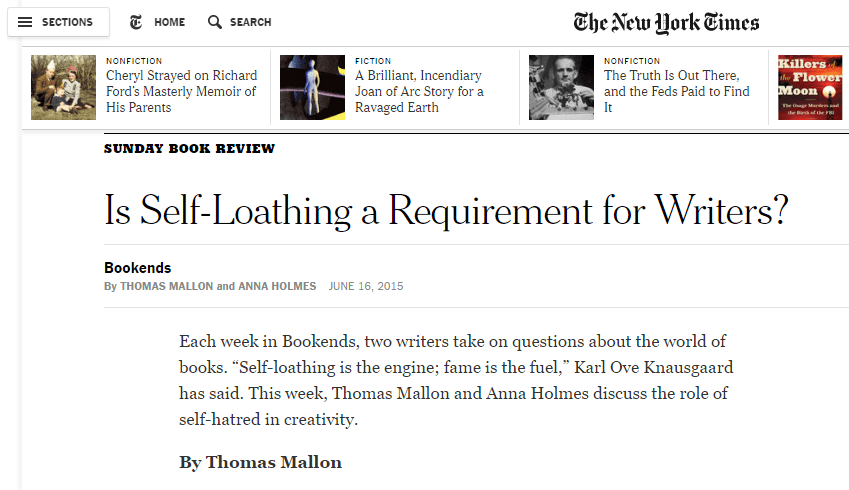

To be completely transparent, that “nine-month” timeframe is slightly misleading. Yes, it’s accurate. (And my revenue has almost doubled since then.) However, it doesn’t account for everything it took to get to a place where that kind of opportunity was possible. I can write. And I’m pretty good at it. But only under very specific circumstances. (And I do mean very specific.) My secret? I cheat. I have almost a decade of hands-on experience in my field. I studied it in school. I was even a good student, believe it or not. I even have an MBA. (And the student loan debt to prove it.) After that, I had a few jobs. Worked in-house at a few companies, putting what I learned into practice, learning new skills, and constantly iterating. Then I left to start my own business. I hired employees, which meant I had to learn how to manage people, scale a business, sell, budget… all of it. The point is, there’s a sweet spot. You’ll thrive when you combine writing with something you’re already skilled at and genuinely interested in. This requires a high level of self-awareness. (You need to be able to critically assess your abilities without falling into the self-loathing that’s so common among writers.)

Yeah, pretty much. Almost everything you do should be specialized in some way.

- The clients you work with.

- The types of websites you target.

- The type of writing you do.

- And so on. I’m not a fiction writer. The New Yorker would laugh me out of the room. I’ve never written for an actual magazine. The thought of writing a whole book terrifies me. And I feel like a complete imposter whenever I send an article to someone who’s a real writer and has actually been published in The New Yorker_. What I can do is write a blog post. A few thousand words, in a witty, slightly sarcastic tone. For people who don’t mind a few off-color jokes here and there. And that’s pretty much it. I’m terrible at everything else. And that eliminates about 99.9% of people and clients who might like what I do (and would be willing to pay for it). Case in point: The first time a new client read an eBook I’d written, her response was, “This reads like a blog post.” Well, yeah.

4. Target an Existing Market

A good close rate in sales is around ~25%. But yours should be closer to 75% or higher. And not because you’re some sales wizard. It’s because you’ve figured out where your specialization is most effective. (Or what tech entrepreneurs call that magical “product-market fit.”) Here’s the secret sauce. You can’t create a market. It either already exists or it doesn’t. Be wary of people and companies that talk about “creating a market” for their product or service. The lack of competition is a huge, flashing red flag.

How to absolutely nail market specialization as a freelance writer. Steve Jobs didn’t invent the first computer. Elon Musk didn’t create the first electric car. And Sergey Brin, Larry Page, and Mark Zuckerberg didn’t invent search engines or social media, respectively. All of these legendary entrepreneurs—founders of some of the most innovative, successful, and profitable companies—didn’t invent their markets. They simply recognized an opportunity and capitalized on it. They perfected it. So look for online “echo chambers.” Because echo chambers are actually large markets!

Interesting. Technology is one example. Social media is another. As is design. WordPress. Gluten-free products. Travel. These are just a few examples off the top of my head. A little research would reveal countless others. Then there are the different content formats: Blogs, magazines, video, podcasts, you name it. The question is, which combination of these variables (a) is willing to pay a decent rate and (b) aligns with your area of expertise? Find that intersection, and your freelance writing career will become infinitely easier. It’ll feel like magic. Here are two signs that you’re on the right track:

- You start receiving unexpected, inbound writing requests.

- Your client retention rate is 80-90% or higher.

5. Focus on Recurring Revenue

Project-based freelancing is often not very profitable.

Here’s why.

Project work tends to be unpredictable. I have no idea why. Maybe it’s the freelance gods messing with us. Whatever the reason, it’s either feast or famine. One month you’re swamped, and the next, you have nothing lined up.

You’re not charging enough. You might land a new project that will “pay the bills” for a week or maybe even a month. But after that, there’s no profit left over. You’re stuck in a rut, just barely staying afloat.

You lack the resources (time, money, energy—take your pick) to do the long-term, brand-building work that will bring you future work.

So, what’s the solution?

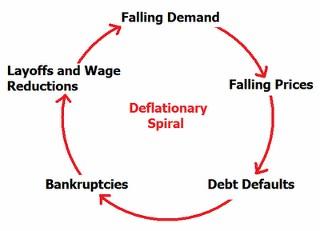

Deflationary economics. Well, not exactly. It’s more like the freelance writer’s answer to deflation.

Here’s what I mean: Consider how technology continually drives down the price of products and services. Take Software as a Service (SaaS) as an example. Or Netflix. Or Spotify. Heck, even custom websites are much cheaper these days, thanks to platforms like Themeforest and 99Designs. Recurring revenue is a game-changer for freelance writers. Without it, you’re stuck scrambling for scraps every 45 days or so, like clockwork. And good luck trying to buy a house, support your family, or hire employees with that kind of income. So, go after recurring revenue no matter what. Even if it means accepting a slightly lower rate per unit.

Me too! Now, you’re not Netflix. Writing as a subscription service isn’t really a viable option yet. It’s a great idea, but there isn’t a significant, profitable market for it (that I’m aware of, at least). The alternative? Think of it like selling consumable products, like razor blades. For instance, people who need articles typically want (or need) to publish a certain number of them each month. So, there’s a built-in demand. That’s where you come in. Provide them with that content every month, consistently. It might mean making a small upfront investment, but you’ll make up for it over six months or more. Sometimes, going after recurring revenue might require you to adjust or modify the service you offer. Do it. You won’t regret it.

6. Continuously Test and Improve Your Value

Let’s face it: most people aren’t good writers. And that’s an understatement. If you need proof, just look at the emails you get from your friends and colleagues.

LOL Writing is a skill, a service. It’s intangible, like selling air. Have you ever tried to write something for someone who’s incapable of writing well themselves? How did that go? My guess is it was a complete nightmare. And that’s precisely why those clients don’t pay writers well. They can’t differentiate between good writing and bad writing, so they don’t see the value in paying a premium. For example, let’s say you’re getting quotes for a website redesign. One person might quote you $1,000. Another quotes you $10,000. And yet another comes back with a quote for $100,000. So, what’s the difference? How does the client decide who to hire? Smart clients (and I’ll admit, that’s a big “if” with some clients) will choose the solution that will generate the highest return on their investment, even if it means paying more upfront. Good clients understand this principle. And remember, you only want to work with good clients. (See tips one and two.) So, your job is to figure out what “value” means to them. If it’s for a website, maybe it means increasing their conversions. If that’s the case, sell them on the value of generating those new leads.

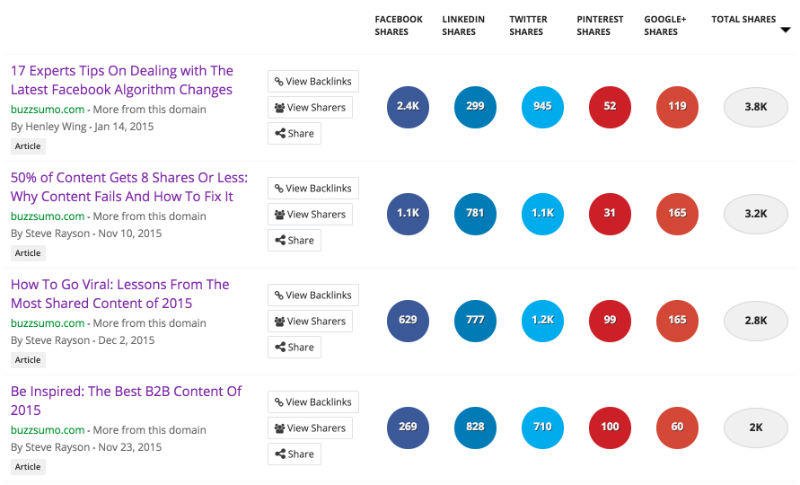

The “value” of writing can be open to interpretation, but not always. The first thing that comes to mind is readership – the dreaded pageview. You can also point to social shares as a metric, as well as organic links or referrals back to a post from other websites.

Generally, the more attention and traffic your writing generates, the more you’ll get paid. It might not always seem fair, but that’s the reality. So, make testing a priority. Experiment with each piece you write. Try a new approach, a different promotional method, a new format or style. Add more images. Write stronger headlines. The possibilities are endless. Is Kanye West the most talented musician out there? Probably not. (And let’s be honest, he’s not exactly known for being a great person.) But he sells records and packs stadiums.

7. Treat Writing Like the Craft It Is

Fitzgerald was a million times the writer most of us can only dream of being. Yet he struggled financially for most of his life, choosing to spend his time pitching magazine articles instead of focusing on his true strength: writing novels. Sadly, he drank himself to death by the age of 45.

There are a couple of common stereotypes about artists. One is that they’re creative. The other is that they’re often starving or struggling in some way. Their work is seen as the result of some divine inspiration. It comes and goes as it pleases. There’s some truth to these stereotypes, but they don’t tell the whole story. The essential word in the title of this article isn’t “writer” but “freelance.” It means you need to approach writing with the same mindset as a ruthless professional. You have to put food on the table. And that means you need to hunt for work.

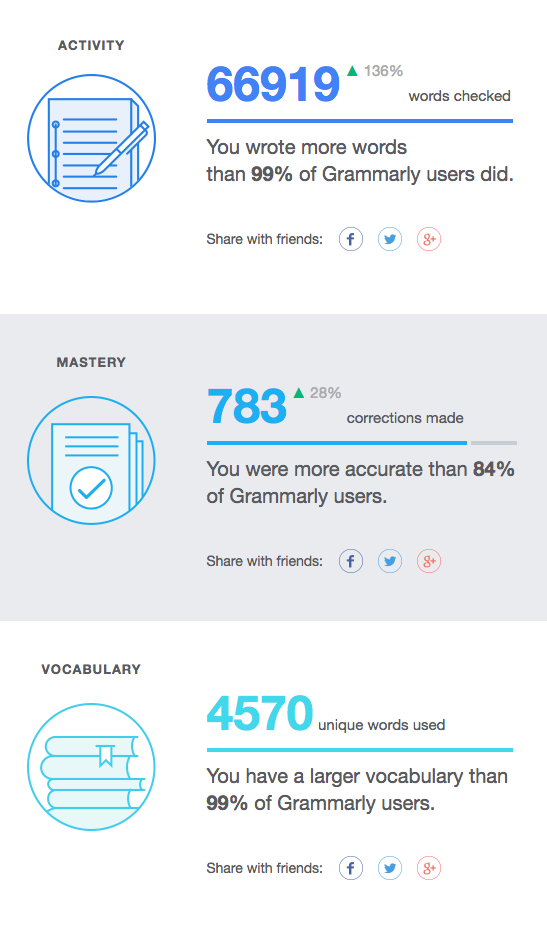

Imagine Christopher Walken discovering the joys of freelancing Renowned food writer Michael Ruhlman refers to cooking as a “craft.” He calls most chefs “craftsmen” rather than “artists.” The difference, he argues, lies in how they approach their chosen profession. A craft demands discipline, unwavering focus, and endless repetition. So don’t break the chain. Don’t shy away from resistance. Face it head-on. Every. Single. Day. I have a whiteboard in my office. Every month, I write down my writing revenue goals, breaking them down into weekly and daily targets. This means that if one day is less productive, I have to make up for it by the end of the week. My goal is to increase that number every month, which means I need to continuously improve my efficiency. That includes things like batching my research, gathering statistics and images in advance, and sticking to strict self-imposed deadlines. (I limit myself to about 3-4 hours per article after the prep work is done so that I don’t overthink or overanalyze things.) My writing also has to improve so that I can reduce the number of edits and revisions requested by clients (ideally to zero!). In short, I have to constantly look for ways to improve every single aspect of my work. Here’s the first step: Admit that you suck. At least in some areas. I know I do. For example, I’ve probably already made a bunch of punctuation errors in this article. That’s why I now run every single article through Grammarly. It helps me eliminate those bad habits, slowly but surely. The best part is that Grammarly sends a weekly progress report so you can track your improvement. It calculates how many words you’ve written, the number of corrections made, and the vocabulary you’ve used over the past week. Then it compares your results against (1) your own past results and (2) all other Grammarly users.

Not a bad week, but there’s always room for improvement! One day at a time, right?

Put in the Work

I enjoy running. But I’ll never qualify for the Boston Marathon. And I have some pretty good excuses. For one, I don’t have the right body type, VO2 max, or any of those other innate “gifts” people like to use as excuses. There’s some science behind them. But the truth is much simpler: I don’t run enough.

No thanks. Runnersworld teamed up with Strava to analyze data from analyze “7,164 marathoners who had run a Boston qualifying time and 24,330 marathoners who had not” during a 12-week marathon training cycle. What they found was that the runners who qualified for Boston ran almost twice as much as those who didn’t (560 miles compared to 300 miles). They also ran almost two more days per week on average. Want to land more freelance writing jobs? Become a better writer. And the way to do that? Write more.

Want more job-related advice?

Check out these recent articles:

- 16 Ridiculously Easy Ways to Find & Keep a Remote Job

- 7 Ways to Make Your Social Media Resume Look Awesome