A lot of front-end and back-end developers are familiar with REST specifications and RESTful APIs. However, it’s important to note that not all RESTful APIs are equal. In reality, they rarely fully adhere to the REST principles.

What Exactly Is a RESTful API?

It’s a bit of a myth.

If you believe your project has a truly RESTful API, you might need to reconsider. The concept of a RESTful API involves strict adherence to the architectural rules and limitations outlined in the REST specification. However, practically speaking, achieving this level of compliance is often impossible.

One challenge is that REST includes many definitions that are unclear and open to interpretation. In practice, for instance, some terms from the HTTP method and status code dictionaries are used in ways that contradict their intended meaning or are completely ignored.

Furthermore, REST development introduces significant constraints. The requirement for atomic resource use, for example, is not ideal for real-world APIs used in mobile apps. Additionally, completely disallowing data storage between requests effectively eliminates the “user session” mechanism, which is nearly universal.

But don’t worry, it’s not all bad!

Why Do You Need A REST API Specification?

Despite these difficulties, when approached thoughtfully, REST remains a valuable concept for building excellent APIs. These APIs can be consistent, well-structured, well-documented, and have high unit test coverage. You can achieve this with a well-defined API specification.

People often confuse a REST API specification with its documentation. Unlike a specification, which is a formal description of your API, documentation is designed for human readability, for example, by developers building mobile or web applications that interact with your API.

Creating a good API description involves more than just writing clear API documentation. This article will highlight ways to:

- Simplify and enhance the reliability of your unit tests.

- Implement user input preprocessing and validation.

- Automate serialization and ensure response consistency.

- Even leverage the advantages of static typing.

Let’s begin with an overview of the world of API specifications.

OpenAPI

OpenAPI is currently the most popular format for REST API specifications. The specification resides in a single file, either in JSON or YAML format, and comprises three main sections:

- A header containing the API name, description, version, and other relevant information.

- Descriptions of all resources, encompassing identifiers, HTTP methods, input parameters, response codes, data types for the body, and links to definitions.

- All definitions that can be used for input or output, formatted using JSON Schema (which, interestingly, can also be represented in YAML).

OpenAPI’s structure has two major downsides: complexity and occasional redundancy. A small project can easily end up with a JSON specification spanning thousands of lines. Maintaining such a file manually becomes an unmanageable task, posing a significant challenge to keeping the specification synchronized with API development.

There are many editors available that facilitate API description and generate OpenAPI output. Additionally, numerous services and cloud-based solutions are built upon them, including well-known options like Swagger, Apiary, Stoplight, Restlet, and others.

However, I found these services cumbersome due to the difficulty in making quick edits to the specification and aligning it with code changes. Moreover, the feature set was often tied to a specific service. For instance, creating comprehensive unit tests using the tools provided by a cloud service was nearly impossible. While code generation and endpoint mocking seemed practical at first, they proved largely ineffective in real-world scenarios. This is primarily because endpoint behavior often hinges on factors like user permissions and input parameters, which might be evident to the API architect but challenging to generate automatically from an OpenAPI spec.

Tinyspec

This article will use examples based on my own REST API definition format, tinyspec. In this format, definitions are structured as small, easy-to-understand files. They describe endpoints and data models used within a project. These files are stored alongside the code, providing quick access and allowing for easy modification during coding. Tinyspec is designed to be automatically compiled into a complete OpenAPI format that can be directly integrated into your project.

While this article will use examples in Node.js (Koa, Express) and Ruby on Rails, the practices demonstrated can be applied to a wide range of technologies, including Python, PHP, and Java.

Where API Specification Excels

With a basic understanding in place, let’s delve into how to maximize the benefits of a well-defined API.

1. Endpoint Unit Tests

Behavior-driven development (BDD) is a perfect fit for REST API development. Instead of writing unit tests for individual classes, models, or controllers, it’s more effective to focus on specific endpoints. Each test simulates a real HTTP request and verifies the server’s response. Node.js offers packages like supertest and chai-http for request emulation, while Ruby on Rails provides airborne.

Let’s assume we have a User schema and a GET /users endpoint that retrieves all users. Here’s how we would represent this using tinyspec syntax:

| |

Now, let’s see how to write the corresponding test:

Node.js

| |

Ruby on Rails

| |

With a specification defining the server responses, we can streamline the test by simply checking if the response conforms to it. We can utilize tinyspec models, each of which can be transformed into an OpenAPI specification adhering to the JSON Schema format.

Any literal object in JavaScript (or Hash in Ruby, dict in Python, associative array in PHP, and even Map in Java) can be validated for JSON Schema compliance. Conveniently, there are plugins available for testing frameworks, such as jest-ajv (npm), chai-ajv-json-schema (npm), and json_matchers for RSpec (rubygem).

Before using schemas, let’s import them into our project. We’ll start by generating the openapi.json file based on the tinyspec specification (you can automate this process to run before each test):

| |

Node.js

Now you can utilize the generated JSON in your project and extract the definitions key. This key contains all the JSON schemas. Keep in mind that schemas might include cross-references ($ref). Therefore, if you have embedded schemas (e.g., Blog {posts: Post[]}), you need to unwrap them for use in validation. For this, we will use json-schema-deref-sync (npm).

| |

Ruby on Rails

The json_matchers module handles $ref references but expects separate schema files in a specific location. To accommodate this, you’ll need to split the swagger.json file into multiple smaller files first:

| |

Here’s how the test would look:

| |

This approach to testing offers significant convenience, especially if your IDE supports test execution and debugging (e.g., WebStorm, RubyMine, Visual Studio). It eliminates the need for using other software, and the entire API development cycle boils down to three steps:

- Define the specification using tinyspec files.

- Write a comprehensive set of tests for new or modified endpoints.

- Implement the code to satisfy the tests.

2. Validating Input Data

OpenAPI not only describes response formats but also input data. This allows you to validate user-submitted data at runtime, ensuring consistent and secure database updates.

Let’s say we have a specification outlining the process of updating a user record, including all permitted fields:

| |

Earlier, we explored plugins for in-test validation. For more general use cases, there are modules like ajv (npm) and json-schema (rubygem). We’ll use these to create a controller with validation:

Node.js (Koa)

This example uses Koa, the successor to Express, but the equivalent Express code would be similar.

| |

In this example, the server returns a 500 Internal Server Error if the input doesn’t match the specification. To handle this more gracefully, we can catch the validator error and construct our own response. This response should provide more detailed information about the specific fields that failed validation and adhere to the specification.

Let’s define a FieldsValidationError:

| |

Now, let’s include it as a possible response for the endpoint:

| |

This method enables you to write unit tests that cover error scenarios when the client sends invalid data.

3. Model Serialization

Most modern server frameworks utilize object-relational mapping (ORM) in some form. This means that resources used by an API are typically represented by models, their instances, and collections.

The process of converting these entities into JSON representations for inclusion in responses is called serialization.

Numerous plugins are available to assist with serialization. Examples include sequelize-to-json (npm), acts_as_api (rubygem), and jsonapi-rails (rubygem). These plugins generally allow you to specify the fields for a model that should be included in the JSON object, along with additional rules. You can rename fields and dynamically calculate their values.

Challenges arise when you need multiple JSON representations for a single model or when dealing with nested entities (associations). This is where features like inheritance, reuse, and serializer linking become crucial.

Different modules offer different solutions, but let’s consider whether the specification can be of help here. Essentially, all the information regarding JSON representation requirements and possible field combinations, including embedded entities, is already present in the specification. This means we could potentially create a single, automated serializer.

Introducing the sequelize-serialize (npm) module, a small utility that accomplishes this for Sequelize models. It takes a model instance or an array and the corresponding schema, then iterates through it to build the serialized object. It also considers all required fields and utilizes nested schemas for associated entities.

Let’s say we want our API to return all users along with their blog posts, including comments on those posts. Here’s how we would describe it in our specification:

| |

Now, we can construct the request using Sequelize and return a serialized object that precisely matches the specification:

| |

It’s almost like magic, isn’t it?

4. Static Typing

For those who appreciate the benefits of TypeScript or Flow, you might be wondering, “What about my beloved static types?”. Using modules like sw2dts or swagger-to-flowtype, you can generate all the necessary static types based on JSON schemas. These types can then be used in tests, controllers, and serializers.

| |

Now, we can leverage types in our controllers:

| |

And in our tests:

| |

It’s worth noting that the generated type definitions aren’t limited to the API project; they can also be used in client application projects to define types for functions that interact with the API. (Angular developers will particularly appreciate this.)

5. Casting Query String Types

If, for some reason, your API handles requests with the application/x-www-form-urlencoded MIME type instead of application/json, request bodies will resemble this:

| |

The same applies to query parameters (e.g., in GET requests). In such cases, the web server won’t be able to automatically determine types. All data will be treated as will be in string format, resulting in the following object after parsing:

| |

Consequently, the request would fail schema validation, requiring you to manually verify the format of parameters and cast them to the appropriate types.

As you might have guessed, our trusty schemas from the specification can assist us here. Let’s assume we have the following endpoint and schema:

| |

A request to this endpoint would look like this:

| |

Let’s define a castQuery function to cast all parameters to the required types:

| |

A more comprehensive implementation that supports nested schemas, arrays, and null types is available in the cast-with-schema (npm) module. Let’s integrate it into our code:

| |

Notice how three out of the four lines of code rely on specification schemas.

Best Practices

Let’s review some best practices to keep in mind.

Use Separate Create and Edit Schemas

It’s common for schemas describing server responses to differ from those used for input validation during model creation and editing. For example, the fields allowed in POST and PATCH requests might be strictly limited, and PATCH requests typically have all fields marked as optional. Schemas describing responses can be more flexible.

When you generate CRUDL endpoints automatically, tinyspec applies New and Update postfixes. User* schemas can be defined like this:

| |

It’s advisable to avoid using the same schemas for different action types. This helps prevent potential security vulnerabilities that could arise from reusing or inheriting older schemas.

Follow Schema Naming Conventions

The content of the same models can vary across different endpoints. Using postfixes like With* and For* in schema names clarifies these differences and their intended purpose. Tinyspec also allows models to inherit from each other. For instance:

| |

Postfixes can be customized and combined as needed. The key is to ensure they accurately reflect the meaning and enhance the readability of the documentation.

Separating Endpoints Based on Client Type

It’s not uncommon for the same endpoint to return different data depending on the type of client or the role of the user making the request. For instance, the data returned by endpoints like GET /users and GET /messages might vary significantly between mobile app users and back-office administrators. Changing the endpoint name can introduce unnecessary overhead.

To describe the same endpoint multiple times, you can append its type in parentheses after the path. This also facilitates the use of tags, allowing you to group endpoint documentation into sections targeted at specific API client groups. For example:

| |

REST API Documentation Tools

Once you have your specification in either tinyspec or OpenAPI format, you can generate visually appealing documentation in HTML format and publish it. This is a much better approach than manually populating REST API documentation templates and will be greatly appreciated by developers using your API.

In addition to the cloud services mentioned earlier, several CLI tools can convert OpenAPI 2.0 to HTML and PDF formats. These tools can be deployed to any static hosting environment. Here are a few examples:

- bootprint-openapi (npm, used by default in tinyspec)

- swagger2markup-cli (jar, there’s a usage example, will be used in tinyspec Cloud)

- redoc-cli (npm)

- widdershins (npm)

If you know of other useful tools, feel free to share them in the comments.

Unfortunately, despite being released a year ago, OpenAPI 3.0 still lacks adequate support. I couldn’t find suitable examples of documentation based on it, both in terms of cloud solutions and CLI tools. For this reason, tinyspec doesn’t yet support OpenAPI 3.0.

Publishing on GitHub

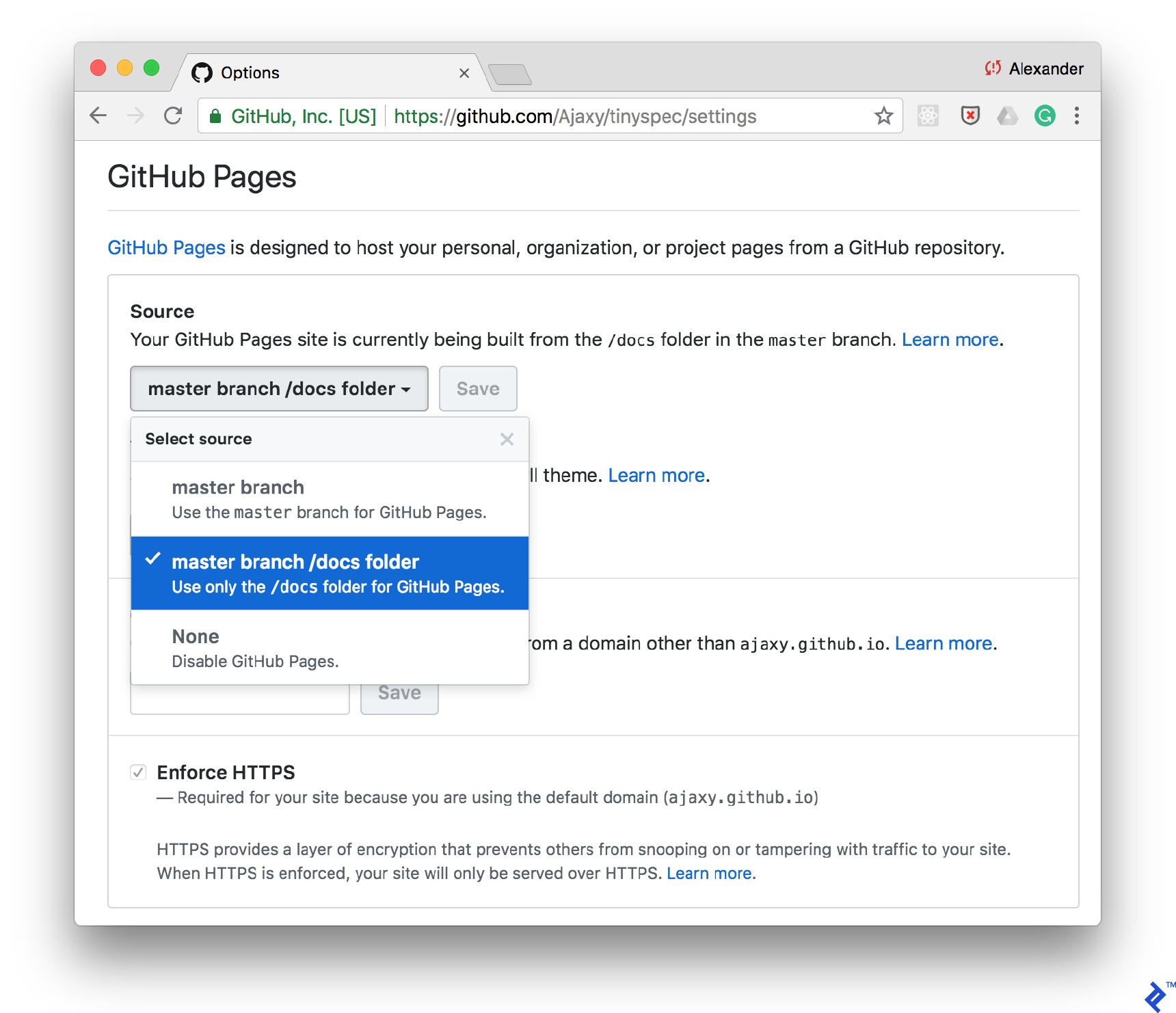

One straightforward way to publish documentation is by GitHub Pages. Simply enable static page support for your /docs folder in the repository settings and place your HTML documentation within that folder.

You can add a command to your scripts/package.json file to generate documentation using tinyspec or another CLI tool. This allows you to automate documentation updates after each commit:

| |

Continuous Integration

You can integrate documentation generation into your CI pipeline and publish it to various destinations, such as Amazon S3, using different addresses based on the environment or API version (e.g., /docs/2.0, /docs/stable, /docs/staging).

Tinyspec Cloud

If you find the tinyspec syntax appealing, you can become an early adopter of tinyspec.cloud. We are developing a cloud service based on it, along with a CLI for automated documentation deployment. It will offer a wide range of templates and the ability to create custom ones.

REST Specification: A Delightful Illusion

Developing REST APIs can be one of the most enjoyable aspects of modern web and mobile service development. You have complete control over the environment, free from the complexities of browsers, operating systems, and screen sizes.

Support for automation and up-to-date specifications further streamlines this process. By adopting the approaches outlined in this article, your API will become well-structured, transparent, and dependable.

Ultimately, if we’re dealing with an illusion, why not make it a delightful one?